Are we fitting children with contact lenses?

Let us face it, we clinicians are a largely conservative bunch. We often do not think about suggesting contact lenses to children and their parents. The literature supports this. For example, in the United States, patients 15 years or less account for only 11% of all lens fits according to 13 years of survey data, representing 7,702 contact lens fits and 1,650 practitioners.1 The numbers are similar elsewhere in the world with children aged six to 12 years and teenagers (13 to 17 years) representing only 1.6% and 11.5%, respectively of over 100,000 fits in 38 countries.2

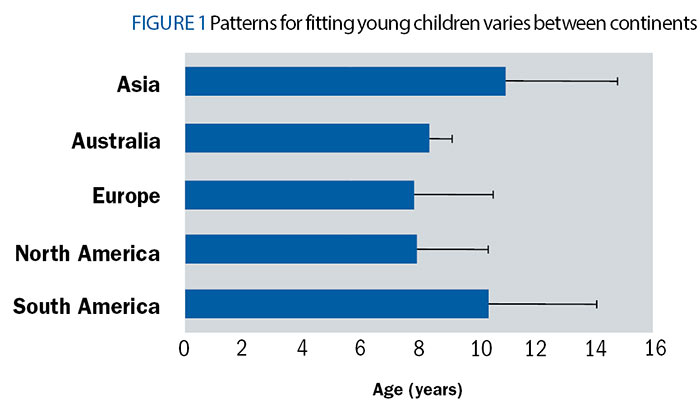

Not surprisingly, optometrists vary widely when it comes to the age of the child at which they introduce contact lenses. Figure 1 shows how the youngest age for fitting soft contact lenses varies by continent.3

Figure 1: Patterns for fitting young children varies between continents

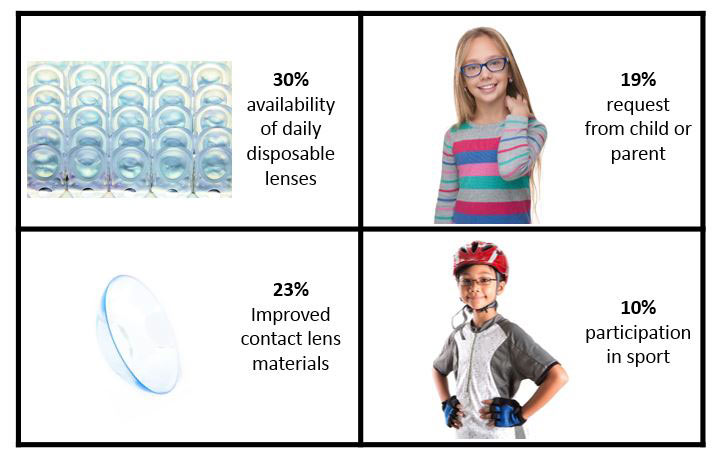

Practitioners do report that they are now more likely to fit children in contact lenses. The most common reasons for this trend include availability of daily disposable lenses (30%), improved contact lens materials (23%), and requests from the child or parent (19%).4 We do see that children are fitted with highest proportion of daily disposable lenses, suggesting safety is a major concern, but is the concern justified?

Time for a Philosophical Reboot?

With the availability of myopia control soft lenses, should we fit more kids? If not, are we missing out on a practice growth opportunity? Given the mounting evidence that even low amounts of myopia increase the risk of debilitating eye disease in older patients, is it ethical to not practice myopia control? But it is also reasonable to ask whether we are placing a child at an unreasonable risk of contact lens related infection. Like so many clinical decisions, it is a matter of comparing risks and benefits.

Gifford and Gifford estimate the lifetime risk of microbial keratitis for a patient wearing daily wear soft contact lenses is one in 75.5 In contrast, the lifetime risk of retinal detachment in a patient with over -5.00 D of myopia is one in 20. These estimates are, however, based largely on data from adults. But can they be extrapolated to children? So let us take an evidence-based deep dive into the data regarding the safety of soft contact lenses in children.

Adverse Events with Contact Lenses

Contact lens-related adverse events fall in two categories – serious and non-serious – with the distinction based on the potential for vision loss. For serious, we usually think of infectious or microbial keratitis. A common definition of microbial keratitis is one or more corneal stromal infiltrates greater than 1mm, pain more than mild, and one or more of following: anterior chamber reaction more than minimal, mucopurulent discharge, or positive corneal culture. Regardless of definition, around one in seven cases of microbial keratitis result in permanent visionloss.6

Non-serious adverse events include contact lens-induced acute red eye (CLARE), infiltrative keratitis, allergic conjunctivitis. We often use the term corneal infiltrative events to indicate corneal involvement beyond mere staining or superficial punctate keratitis. Patients are sometimes unaware of corneal infiltrative events, so we can define symptomatic corneal infiltrative events as the presence of non-infectious infiltrate, hyperaemia, and discomfort.

It is the frequency of the above adverse events that inform us on the safety of contact lenses.

Understanding the Data

Before we get into the numbers, let us briefly review some basic, easy to interpret, but important, statistics. Still reading? Good. Any estimate we make carries some uncertainty that must be stated in order to give the full picture. For the mean, also referred to as the average, we express the uncertainty as the standard deviation. The larger the standard deviation, the less precise our estimate of the mean. For percentages or proportions, like the number of people who prefer butter to margarine, we give the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Even if you are not familiar with that specific term, you have heard it reported as the ‘margin of error’ for the endless opinion polls that precede elections and referenda. The more people that we survey, the narrower the 95% confidence interval or the smaller the margin of error.

In patient-based clinical studies, we are frequently interested in the incidence – the number of cases occurring in a given time period. For example, if six cases are observed in 723 patients followed for a year, we can estimate the incidence to be 0.0083 cases per year. If we have access to a house-trained statistician or the internet, we could ascertain that the 95% confidence intervals are 0.0034 to 0.0173. Now all these decimal places are an occupational hazard when dealing with relatively rare conditions like contact lens-related infections, and they are tough to digest. Thus, we often report them in more friendly terms: 83 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 34, 173). A large study estimated incidence of severe microbial keratitis (with permanent loss of visual acuity) in daily wear of soft lenses to be 0.00080 (95% CI: 0.00067, 0.00098). It’s much easier to report and interpret as eight per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 6.7, 9.8).6 In other words, we would expect to see eight cases of severe microbial keratitis each year per 10,000 patients, but maybe as many as 9.8.

For adults in daily wear soft contact lenses, the incidence of corneal infiltrative events has been estimated as 300 to 400 per 10,000 patient years in recent large-scale studies.7-9 Obviously, these are much more common than sight-threatening microbial keratitis, but what about children, these eight to 12-year-olds who represent our candidates for myopia control?

Big Data and Microbial Keratitis

What can major epidemiological studies tell us about incidence of events in children wearing contact lenses? The short answer is not much, except that children are rarely represented in large epidemiological studies of contact lenses. Three major papers from a decade ago collectively represent some 900 cases of presumed or confirmed microbial keratitis.6,10,11 All three studies only report cases in patients 15 years and older. It is unclear whether this represents absence of paediatric cases or a study design decision.

Nonetheless, we cannot assume cases of microbial keratitis do not occur in children wearing contact lenses. Several retrospective studies of hospital populations report cases in children. In a 10-year study of microbial keratitis at the National Taiwan University Hospital, 22 of the 453 patients were 15 years or younger (4.9%).12 Contact lens use accounted for 44% of all cases, but the authors do not provide details regarding the aetiology and severity of the paediatric cases, nor types of lenses worn. There are three similar case series from Taiwan and Hong Kong limited to microbial keratitis in children.13-15 Contact lenses account for over half the cases with orthokeratology and soft lenses both represented. Nonetheless, these kinds of studies do not inform us of the frequency, or incidence, of serious events.

Evaluating the Risk in Children

But surely there are studies of safety of the incidence of soft lenses in children? Why yes there are. Let us start with the retrospective Contact Lens Assessment in Youth (CLAY) Study.16 This was a meticulous, multicentre, retrospective, observational study that evaluated risk factors that interrupt soft contact lens wear among children, teenagers, and young adults in North America. The study’s goal was to assess the safety profile of soft contact lens wear in paediatric population outside confines of prospective clinical studies, by focusing on patients presenting to academic eye care clinics for routine and problem-oriented eye care.

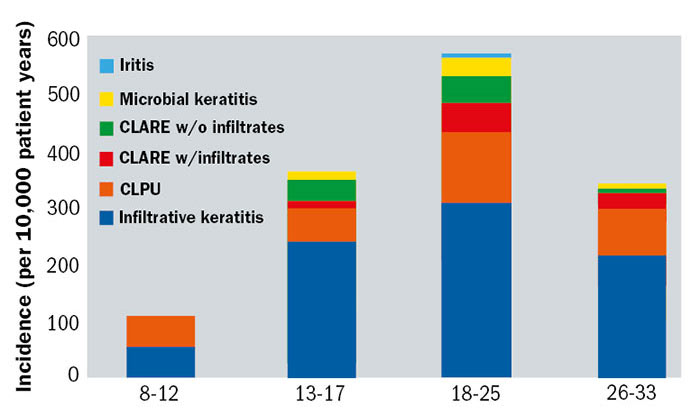

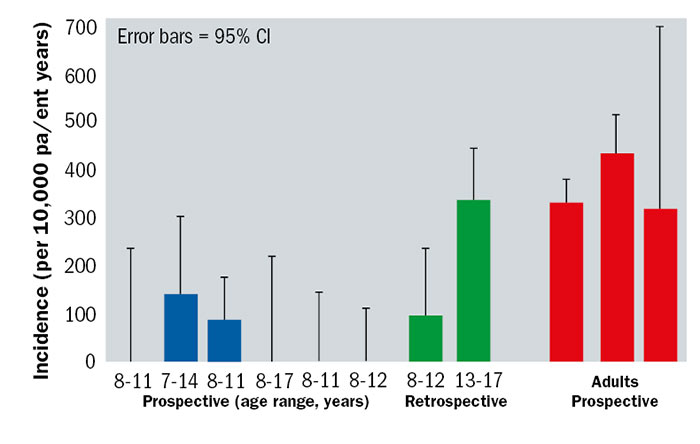

The investigators reviewed charts from 3,549 patients, representing 14,276 office visits.8 Existing soft contact lens wearers accounted for 79% of patients, and new fits, 21%. Children represented around a third of the sample with 270 under 13 years and 879 between 13 and 17 years. Across all patients there were 187 corneal infiltrative events over 4,663 soft contact lens patient years. Importantly, the incidence varied dramatically with age as demonstrated in the Figure below. The eight to 12-year-olds have dramatically lower rates of adverse events than teenagers. In contrast, young adults had markedly higher rates. The incidence of corneal infiltrative events for eight to 12-year-olds was 97 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 31, 235) compared to 335 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 248, 443) in 13 to 17-year-olds. For adolescents, the incidence is even higher.

Consistent with previous studies, only eight of these events were classified as microbial keratitis. Importantly, no cases of microbial keratitis were observed in the younger children compared with two cases among the teenagers (incidence = 15 per 10,000 patient years) and five cases among the university-age patients (incidence = 33 per 10,000 patient years). In summary, both corneal infiltrative events and microbial keratitis are much less common in eight to 12-year-old children. Figure 2 summarises the incidence of adverse events for different age ranges.

Figure 2: The incidence of adverse events for different age ranges

Regarding Teenage and Adolescence Behaviour

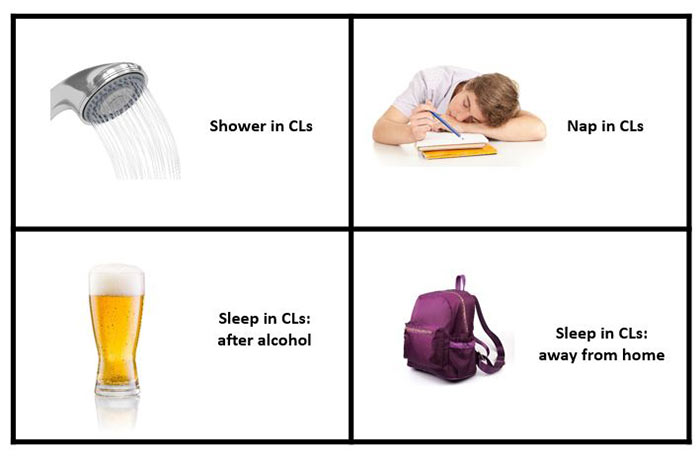

An important aspect of the observed increase in adverse events in teenagers and college kids is that it is related to changes in behaviour and not biology.17 This will, of course, come as no surprise to parents. Behaviours related to increased risk of contact lens-related infections were much, much more common in teenagers and adolescents than in the children. These risky behaviours included showering and sleeping in lenses, with the latter increasing when travelling, drinking, and being away from home.

Behavioural risks in CL use

Reasons to fit children with CLs

Prospective Studies of Soft Contact Lenses in Children

So, we have comprehensive data from a thorough chart review, but what about prospective studies? There is a growing list of publications on myopia control using multifocal soft contact lenses in children. Unfortunately, nearly all fail to report safety outcomes, even though the children were obviously examined regularly over one or two years. Likewise, there are studies of fitting success and lens handling in children, but these are too small or too short to provide estimates of incidence.

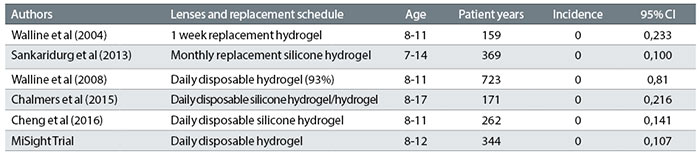

There have been six published studies reporting safety outcomes with at least 150 patient years of lens wear. The incidence of corneal infiltrative events along with other information is summarised in the table 1, but let us look at the three largest, some of which you may have encountered before.18-22

Table 1: Summary of studies into adverse event risk in young children

The ACHIEVE Study assessed the influence of soft lenses on self-esteem in 584 myopic children aged eight to 11 years.22 Of these, 237 were randomised to wear spectacles and 247 to (mostly daily disposable) soft contact lenses. Over the three-year trial, representing 723 patient years of contact lens wear, there were no cases of microbial keratitis in the contact lens wearers and just six presumed cases of corneal infiltrative events – an incidence of 83 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 34, 173).

The Brien Holden Vision Institute reported on 240 children aged seven to 14 years wearing silicone hydrogel lenses worn on a daily wear–monthly replacement schedule.20 The two-year study represents 369 patient years of contact lens wear. Again, there were no cases of microbial keratitis. Among the 55 non-serious events, there were five cases of infiltrative keratitis and 13 instances of asymptomatic infiltrates. The incidence of symptomatic corneal infiltrative events was 136 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 50, 300).

Finally, in the recently completed CooperVision MiSight Three-Year Clinical Trial, 132 children aged eight to 12 years were randomised to MiSight or Proclear lenses resulting in 344 documented patient years of lens wear. There were no cases of microbial keratitis and just four corneal infiltrative events giving an incidence of 116 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 37, 280). Furthermore, all of these infiltrates were observed at scheduled visits, so they should be considered asymptomatic. Thus, the incidence of symptomatic corneal infiltrative events is 0 per 10,000 patient years (95% CI: 0, 108).

In conclusion, it is possible to make a valid assessment of the safety of soft contact lenses in children by comparing a number of different studies.23 Looking at table 1, four of the six studies observed no corneal infiltrative events, but the 95% confidence intervals can still be estimated. Note that the upper limit never exceeds 300 per 10,000 patient years. Figure 3 summarises the incidence of corneal infiltrates in children, teenagers and adults and the comparison is striking. The overall picture is that the incidence of corneal infiltrative events in children is markedly lower than in adults. The upper confidence interval never reaches the estimated incidence in older patient groups. The prospective studies of children represent over 2,000 patient years of soft contact lens wear. Combining the six prospective studies, the estimated incidence of corneal infiltrative events in children is per 54 per 10,000 patient years and the upper 95% limit is 86 per 10,000 patient years. In other words, each year, no more than 86 cases of corneal infiltrative events each year per 10,000 patients. In contrast, we would expect to see 300 such events in adults.

Figure 3: The incidence of corneal infiltrates in children, teenagers and adults

Take Home Message

If children 12 and younger can handle contact lenses, then we should not be unusually concerned about safety. The frequency of adverse events is lower in these younger children than in teenagers, university students and young adults. Furthermore, the likelihood of microbial keratitis is negligible, with no reported cases in over 2,000 prospective and 400 retrospective patient years of lens wear. Daily disposable soft contact lenses may reduce corneal infiltrative events in all patients, including children. So, as we press forward into the brave new world of myopia control in children, soft contact lenses should be high on our list of treatment options.

Vigilance is still needed in spite of the low incidence of microbial keratitis in children. As they say, ‘it ain’t rare if it’s in your chair,’ so we must educate all patients on the importance of good hygiene and list risky behaviours that can have consequences. Any patient with an uncomfortable red eye needs to be seen promptly and managed appropriately.

Professor Mark Bullimore is a British-trained optometrist and scientist, former president and development director of the American Optometric Foundation and the former editor of Optometry and Vision Science, and executive director of the World Council of Optometry.

Author’s Note

A comprehensive discussion of this topic can be accessed here:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5457812/pdf/opx-94-638.pdf

References

- Efron N, Nichols JJ, Woods CA, Morgan PB. Trends in US contact lens prescribing 2002 to 2014. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92:758-67.

- Efron N, Morgan PB, Woods CA, International Contact Lens Prescribing Survey Consortium. Survey of contact lens prescribing to infants, children, and teenagers. Optom Vis Sci 2011;88:461-8.

- Wolffsohn JS, Calossi A, Cho P, Gifford K, Jones L, Li M, Lipener C, Logan NS, Malet F, Matos S, Meijome JM, Nichols JJ, Orr JB, Santodomingo-Rubido J, Schaefer T, Thite N, van der Worp E, Zvirgzdina M. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2016;39:106-16.

- Sindt CW, Riley CM. Practitioner attitudes on children and contact lenses. Optometry 2011;82:44-5.

- Gifford P, Gifford KL. The Future of Myopia Control Contact Lenses. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93:336-43.

- Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, Naduvilath T, Dart JK, Brian G, Holden BA. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1655-62.

- Chalmers RL, McNally JJ, Schein OD, Katz J, Tielsch JM, Alfonso E, Bullimore M, O’Day D, Shovlin J. Risk factors for corneal infiltrates with continuous wear of contact lenses. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:573-9.

- Chalmers RL, Wagner H, Mitchell GL, Lam DY, Kinoshita BT, Jansen ME, Richdale K, Sorbara L, McMahon TT. Age and other risk factors for corneal infiltrative and inflammatory events in young soft contact lens wearers from the Contact Lens Assessment in Youth (CLAY) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:6690-6.

- Szczotka-Flynn L, Jiang Y, Raghupathy S, Bielefeld RA, Garvey MT, Jacobs MR, Kern J, Debanne SM. Corneal inflammatory events with daily silicone hydrogel lens wear. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91:3-12.

- Dart JK, Radford CF, Minassian D, Verma S, Stapleton F. Risk factors for microbial keratitis with contemporary contact lenses: a case-control study. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1647-54, 54 e1-3.

- Keay L, Edwards K, Stapleton F. Signs, symptoms, and comorbidities in contact lens-related microbial keratitis. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86:803-9.

- Fong CF, Tseng CH, Hu FR, Wang IJ, Chen WL, Hou YC. Clinical characteristics of microbial keratitis in a university hospital in Taiwan. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137:329-36.

- Hsiao CH, Yeung L, Ma DH, Chen YF, Lin HC, Tan HY, Huang SC, Lin KK. Pediatric microbial keratitis in Taiwanese children: a review of hospital cases. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:603-9.

- Lee YS, Tan HY, Yeh LK, Lin HC, Ma DH, Chen HC, Chen SY, Chen PY, Hsiao CH. Pediatric microbial keratitis in Taiwan: clinical and microbiological profiles, 1998-2002 versus 2008-2012. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157:1090-6.

- Young AL, Leung KS, Tsim N, Hui M, Jhanji V. Risk factors, microbiological profile, and treatment outcomes of pediatric microbial keratitis in a tertiary care hospital in Hong Kong. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:1040-4 e2.

- Lam DY, Kinoshita BT, Jansen ME, Mitchell GL, Chalmers RL, McMahon TT, Richdale K, Sorbara L, Wagner H, Group CS. Contact lens assessment in youth: methods and baseline findings. Optom Vis Sci 2011;88:708-15.

- Wagner H, Richdale K, Mitchell GL, Lam DY, Jansen ME, Kinoshita BT, Sorbara L, Chalmers RL, Group CS. Age, behavior, environment, and health factors in the soft contact lens risk survey. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91:252-61.

- Chalmers RL, Hickson-Curran SB, Keay L, Gleason WJ, Albright R. Rates of adverse events with hydrogel and silicone hydrogel daily disposable lenses in a large postmarket surveillance registry: the TEMPO Registry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:654-63.

- Cheng X, Xu J, Chehab K, Exford J, Brennan N. Soft Contact Lenses with Positive Spherical Aberration for Myopia Control. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93:353-66.

- Sankaridurg P, Chen X, Naduvilath T, Lazon de la Jara P, Lin Z, Li L, Smith EL, 3rd, Ge J, Holden BA. Adverse events during 2 years of daily wear of silicone hydrogels in children. Optom Vis Sci 2013;90:961-9.

- Walline JJ, Jones LA, Mutti DO, Zadnik K. A randomized trial of the effects of rigid contact lenses on myopia progression. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:1760-6.

- Walline JJ, Jones LA, Sinnott L, Manny RE, Gaume A, Rah MJ, Chitkara M, Lyons S, Group AS. A randomized trial of the effect of soft contact lenses on myopia progression in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008;49:4702-6.

- Bullimore MA. The Safety of Soft Contact Lenses in Children. Optom Vis Sci 2017;94:638-46.

This article was written with support from CooperVision

Optician CooperVision Myopia Series

Part 1: The concern about myopia prevalence – Professor Desmond Fonn

Part 2: What does a good myopia control study look like? Part 1 – Dr Kathy Dumbleton

Part 3: What does a good myopia control study look like? Part 2 – Dr Kathy Dumbleton

Part 4: Why fitting contact lenses in young children is safe? – Professor Mark Bullimore

Part 5: Three year milestone results in contact lens myopia control – Dr Paul Chamberlain