It has long been recognised that magnification can assist a visually impaired patient, or indeed any patient, in undertaking a variety of tasks, and therefore offer the chance to improve their quality of life and perhaps maintain independence. In the past, many low vision practitioners tended to shy away from recommendation of electronic low vision aids (which historically tended to be grouped together as CCTVs), or to use the preferred terminology ‘electronic visual enhancement systems’ (EVES), often, but not exclusively, due to cost factors or the patients unfamiliarity with electronic and computer-based devices.

Computers and electronic devices are now well established in everyday life; in schools, work environments and the home. Patients attending low vision clinics are increasingly computer literate, some having had prior years of experience perhaps in their current or previous jobs or indeed at home. Manufacturers of electronic low vision aids have also moved with the times, from supplying a limited range of aids to a now fairly extensive selection.

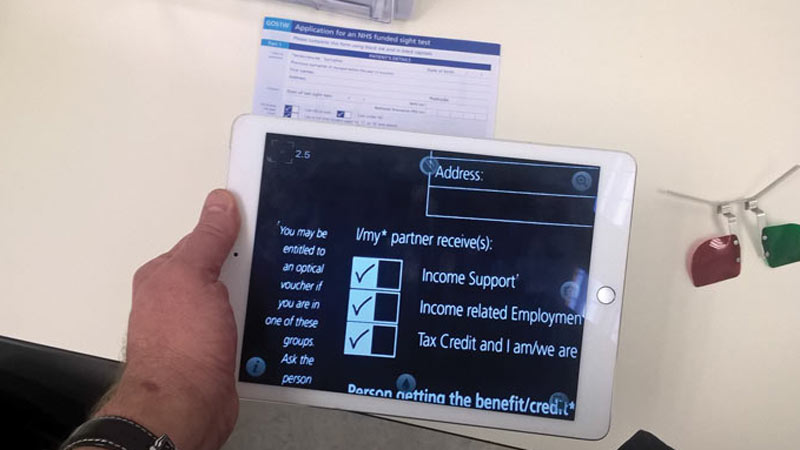

A patient’s success with a low vision aid does not just rest solely on acuity and other clinical measures, but is influenced by real life considerations such as ease of use and cosmesis. Electronic devices nowadays are usually simple to use, often more so than a standard optical magnifier, and additionally have the advantage of being perceived as more socially acceptable. Indeed, there has been rapid development in software used by existing electronic devices, such as tablets (figure 1) and smartphones, and these can offer often very cost-effective options using a medium everyone is familiar with and unlikely, therefore, to suffer some of the stigma associated with many low vision aids.

Figure 1: Use of a tablet and a magnification app

Who Are They For?

EVES essentially present a magnified image upon a screen and may be complemented with further attempts at magnification, such as reduced working distance.

Experienced low vision practitioners will be aware that the philosophy in the past was that electronic aids were only for the young and highly motivated visually impaired persons. Though this may obviously still hold some truth, encouragement of all age groups should now be the norm. Success with any low vision aid however, does still depend on a degree of motivation and similar criteria for suggesting an optical magnifier should therefore still be used if recommending an EVES.

As with traditional optical magnifiers, the prior assessment of visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and visual fields remains essential. Common sense dictates the better these three factors are, the better the success with the aid will be. From experience, the author has found that EVES will only have limited success if the acuity is worse than logMAR 1.20, and/or the contrast sensitivity worse than 22% (0.60 log CS), though some highly motivated patients may still surprise you. Practitioners should not ignore the fact that there may be audio options with some devices that will enhance performance in the more significantly sight impaired.

Unlike traditional optical magnifiers, EVES are usually not available for funding via the NHS. This is changing, however, and the Welsh Low Vision scheme, for example, offers the supply of an EVES device where its usefulness can be argued. Also, as many patients already own computers, tablets and smartphones, access to electronic magnification is often very cheap and easy.

There is statutory provision, following assessment, for those who are deemed eligible; ie for those in full time education, or those in employment via the ‘Access to Work’ scheme (throughout the UK except Northern Ireland).1

For those in education, children are ‘statemented’ and receive a Statement for Special Educational Needs (SEN) which outlines the help they require which may include EVES (figure 2). The Access to Work scheme provides practical support and financial help for those with visual impairment, and other disabilities. Some charities may help certain individuals, for example St Dunstan’s (Blind Veterans UK) may help those previously or indeed currently in the armed forces. If not, eligible patients will need to purchase EVES privately, with some charities (eg Macular Society) offering limited help and possibly access to second hand markets which may reduce costs.

Figure 2: Child using a smartphone reading enhancement app

The p-EVES Study

The p-EVES Study was designed to answer the question of whether p-EVES devices offer real benefits to users for near tasks and activities, in addition to traditional optical LVAs.2 The p-EVES Study was a prospective two-arm cross-over randomised controlled trial to determine the clinical effectiveness, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness of p-EVES devices compared to optical LVAs.

Overall, maximum reading speed for high contrast sentences was not significantly different between optical aids and p-EVES, although the critical print size and threshold print size which could be accessed with p-EVES were significantly smaller (p<0.001 in both cases), due to the higher magnification available. However, p-EVES were preferred for leisure reading by 70% of participants and allowed longer duration of reading (p<0.001). Although the original hypothesis was that p-EVES would be more versatile, and might replace several other devices, in fact the optical aids were used for a larger number of tasks (p<0.001) and used more frequently (p<0.001). The p-EVES is therefore an extra device in the clinician’s armoury, in that it complements rather than replaces other aids for near vision.3

The findings of the p-EVES Study are sufficiently positive to support a bid to commissioners of services to introduce p-EVES supply as a potential service development in NHS clinics throughout the UK, so they can meet the requirements of the Joint Strategic Needs Assessment for Eye Care and Sight Loss Services.4

Advantages of EVES

There are several advantages of EVES. As in many respects with developments in technology and an increasing number of computer literate patients boosting demand, EVES are relatively simple to use and can be operated at variable working distances. Furthermore, the devices can be shared easily between users and also have the benefit of offering real image magnification. In a similar vein, they may be more socially acceptable as they draw attention to the casual observer that the user has a visual impairment. Unlike many magnifiers, EVES can be used binocularly at a more natural (and usually variable) working distance and with a more comfortable posture. This may not be an advantage if the patient is not binocular or needs to supplement the device with, for example, a hand or stand magnifier.

From experience, with desktop-based devices, the majority of patients seem to work comfortably at about 40cm although this will vary with patient and device. As with any computer user there is always the risk of repetitive strain injury so the prescribing clinician would be well advised to go over carefully all the advice about careful set up of the work station and the need for appropriate lighting and regular breaks. EVES can be used for a variety of tasks including viewing print, medicine bottle labels and sometimes photographs, though the actual tasks will again be device and patient specific.

From a more technical point of view, further advantages include a variety of additional features available for any particular device, though yet again this depends on the exact device and whether the patient needs the adaptation. These features include:

- monochrome and colour options (including reverse polarity)

- contrast control

- text editing, including highlighting

- text isolation

- adjustable magnification (with achievable magnification to 65X +)

- zoom functions

- variable screen illumination/ luminance (brightness)

- adjustable font size

- split screen options including horizontal and vertical masking options

- optical character recognition and voice output

Disadvantages

Unsurprisingly there are disadvantages to EVES. With a lack of funding, for many patients cost can be a major inhibitory factor. Though EVES are less expensive than previously was the case when first introduced, it remains a considerable outlay, especially for a device with a limited time of usefulness (as is often the case with the very elderly or those with a progressive condition). Some manufacturers allow patients to trial devices before purchasing. Some larger low vision resource centres may have devices to try ‘on site’ with staff available to aid selection and give training. In addition, some low vision clinics may also have visiting staff at specific times who will demonstrate a selection of EVES. As with any equipment of this nature there is a risk of them developing faults which may be complicated to rectify, and as the value of the device will depreciate quickly users may have to decide if they feel it is worthwhile to repair.

As with any technology, EVES will become outdated relatively quickly, though to most patients, this is not a disadvantage per se. Due to the nature of the device, frequently a power supply is required which, if mains only, may reduce portability and a possible increase in risk of becoming a trip hazard. If battery powered, this could also be considered a disadvantage due to the costs and changing the batteries can sometimes be a challenge in itself, though many suppliers and manufacturers have made significant improvements to facilitate an easier access to battery compartments. Readers may agree that this point applies to all illuminated low vision aids. Even though many traditional optical magnifiers may also require battery power, the battery life is frequently longer with these as compared with EVES. It could also be argued that electronic devices need more maintenance than optical ones, though this is debateable.

With the larger devices portability may be limited anyway, though there are an increasing number of portable choices which will be discussed later. A disadvantage with earlier portable devices was a lack of robustness and durability, with some early adopters suffering breakages and damage after just a few excursions. Robustness has improved greatly in recent years. The additional training required for optimal usage may be a hindrance to some, but it should not be forgotten that even simple hand magnifiers may need training. The aforementioned advantage of availability of higher magnification with EVES leads to the disadvantage, as with any magnification system, of a poorer field of view. As expected the optimal use including best reading speeds will be achieved when using minimum magnification as will give the patient the maximum field of view. There may also be, depending again on the device, some difficulty with examining curved surfaces or objects.

Design

Basically, an EVES is a camera with a monitor. Many older low vision references may often refer to these devices as ‘CCTV for low vision’ as this is, in simplistic terms, what the devices are. The camera may be fixed or adjustable. The image is a ‘live view’ but some devices may have the option of saving or recording or capturing ‘stills’. Larger devices sometimes have a foot pedal to facilitate this. As with digital cameras, the modern EVES usually have some degree of variable focus with the most advanced being able to manage distance, intermediate and near vision tasks, with either a single camera or a dual camera system. Some of the desktop devices have a moveable integral table, usually on an X-Y platform, particularly useful for steady eye strategy (this is where the user moves the target under view while keeping their eyes and gaze still – a big help when a central scotoma is off centre towards the side they read towards). As with a standard desktop, or indeed a connected laptop, pivotal screens can be incorporated to assist posture.

There are several categories of EVES:

- video magnifier (desktop or ‘laptop’)

- portable (pocket or head mounted)

- TV readers

There are a number of manufacturers and suppliers of EVES, each having different ranges and hence options and costs. Both practitioners and perhaps more importantly patients should be allowed to choose according to needs and financial considerations. The author does not wish to influence any decision making so the aids described forthwith are generic descriptions. A good start for those interested in looking at individual designs and their features, RNIB website (rnib.org.uk) and follow the ‘electronic’ link.

Desktop

The desktop magnifier (figure 3) is analogous in many ways with the traditional desktop PC or Mac, and the more portable versions comparable to a laptop or MacBook (or larger tablet). These are traditional ‘CCTV’ devices with a camera, light source and monitor, with some having the option of attaching (or buying as integral) the aforementioned X-Y platform. The disadvantage of the desktop devices is they are not portable and require dedicated space.

The portable ‘laptop’ versions can also be heavy and bulky but offer larger monitors/screens than the true portable devices.

Figure 3: Desktop magnifier

Portable

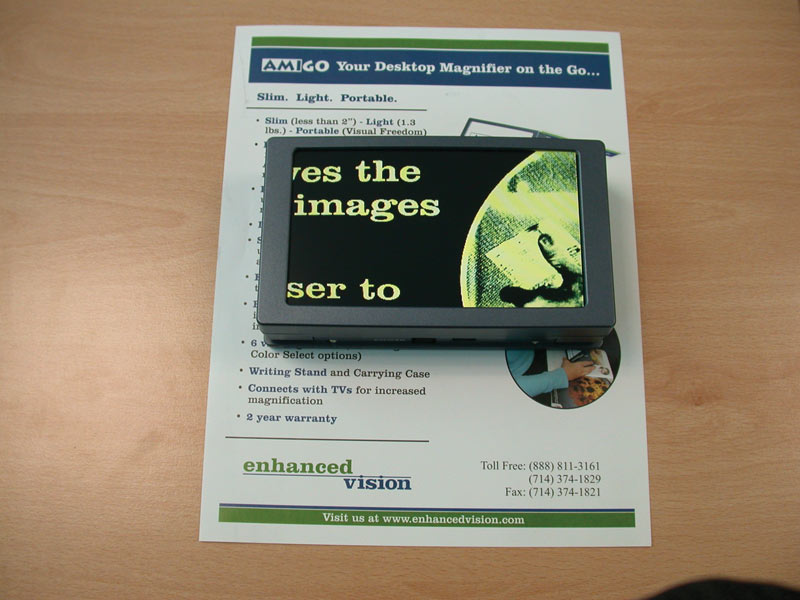

The truly portable devices usually have an ‘all in one’ integral screen and camera which may have the additional feature of being connectable to a larger laptop or desktop device or indeed head mounted visors (figure 4). These devices are similar to a smaller conventional tablet, are handheld and will fit into a briefcase or similar sized bag. Smaller portable devices specifically for visually impaired users are also handheld with an integral camera and screen. They are about the size of the ‘mini’ tablets which are currently popular. They can be battery, rechargeable or mains operated, the latter for use at home to save the integral battery.

Figure 4: Portable magnifying device

There is usually variable, though limited, magnification and such a device is useful in shops, restaurants and libraries. The more expensive devices may include some editing options. These devices are lightweight, and as with other EVES, often come with the option to connect to a larger screen or headset, and also capture images for playback. In addition, there are the even smaller ‘pocket devices’ which are similar in size to a smartphone. These have the same advantages and disadvantages as the portable devices with the additional disadvantage of the small screen area which may cause problems with higher magnifications (figure 5).

Figure 5: Small magnifying device

Head mounted devices are usually LCD screens, often with an integral positive lens. The camera may be part of the head mounting or hand held. They usually offer good magnification, and decent contrast thus allowing for good acuity (if possible). They offer some degree of portability and are useful (in the more expensive versions) of being adjustable for distance, immediate and near, and usually offer a decent field of view. They are surprisingly lightweight and come in compact and hence more portable options. They are available in battery and mains-controlled options and may come with docking stands as an optional extra. Unfortunately, these devices are not popular with patients, or indeed practitioners. They are difficult to fit comfortably and some patients experience symptoms of claustrophobia. Steady control is also required. Without high motivation and perseverance, performance is reduced from optimal; notably dynamic visual acuity is often reduced with these devices.

TV readers

TV readers are an inexpensive option and hence popular with patients particularly those who are self-financing. These are essentially a portable camera which then plugs directly into a PC or TV as the monitor. The connection can be via USB or SCART. The magnification is usually limited or indeed fixed with typical magnification is 16-28X. The devices usually look like a handheld computer ‘mouse’ (figure 6). The least expensive will be simple black and white; more expensive readers will have colour options, and possibly the option for reverse polarity. These are truly portable but do require a monitor, but nonetheless useful for domestic use as most households will have a TV or computer.

Figure 6: TV reader using a mouse

As referred to earlier, there are many devices available in the domain of the general population. These include your standard desktops and laptops which may have built-in cameras or have a USB port for a webcam, as well as editing and accessibility options. Also, regularly available tablets, smartphones and eBook readers may also be suitable for many visually impaired patients, possibly at a fraction of the cost to specifically manufactured devices. Kindle software, for example, is available for most devices and offers both magnification, contrast reversal and, for selected titles, audio options.

From a practical application the practitioner needs to balance magnification with field of view and reading speed. An increase in magnification may result in improvement in reading speed, but a further increase may have a detrimental effect due to the decrease in the field of view, though all these factors will be affected by the working distance. Each user should be considered and assessed individually and practitioners should be wary of making pre-assessment assumptions about a user’s capability with a device. Be prepared for a surprise with many patients.

Software

As discussed, there are a variety of specifically designed hardware options, but you cannot discuss EVES without mentioning briefly the specifically designed software options. The modern standard computers, tablets and smartphones may have built in magnification, contrast, speech and audio options and these are often limited, though there are some good applications available. For a PC, have a look at the ‘accessibility options’ available on all modern systems.

Specialised programmes for magnification, audio and speech are available. Relatively simple options may be available for free download, including ‘read aloud’ and talking keyboard options, but they have limited functionality, may have electronic voices some patients may find irritating and the magnification options may sometimes pixelate the image to the extent it becomes more difficult to see than at the original size. Specialised screen magnification software magnifies the screen image without pixelation, and with smooth edges. Rather than having the whole screen magnified, the user may have the option of selecting a particular area or a split screen/letterbox option thus customising the view. The disadvantage is the limited area on view often exacerbated by screen size. There may be options to alter the colour which some patients find more comfortable, for example blue on yellow. The mouse cursor can be changed to make it more visible than the standard options, and some programmes also come with an audio keyboard.

Screen readers essentially enable the computer to talk. It reads the screen for the user and synthesises it into recognisable speech. These can be user defined to reading specific areas or the whole screen, including menus and dialog boxes. Punctuation, symbols and acronyms are easily recognised. Standard text to speech software is a less expensive (or even free) option. Also readily available is dictation software. After a controlled set up, a user can dictate text including punctuation layout, acronyms and symbols.

Another option is an OCR (optical character recognition) reader. A hard copy document is scanned and the software recognises the words and converts them into easy read documents or, with screen reader software, reads them to the user. The more expensive options can recognise handwritten documents. There are standalone OCR scanning systems as well as integral options.

The OrCam

The OrCam is one example of a spectacle mounted device capable of object recognition that then informs the wearer of what is being viewed. It is likely that, in the coming years, smart screen spectacle devices and adapted frames will become more readily available and offer fully portable magnification and identification options for a patient.

Figure 7: The OrCam

Keep an Open Mind

Though there are studies which indicate that certain patient attributes may influence success with EVES, practitioners should not assume that success can be completely predicted from the patient’s age, gender, underlying pathology, length of diagnosis, emotional status or even previous experience and hence should keep an open mind when suggesting them as a viable option. As with any low vision aid the practitioner should consider physical constraints (with hand held options, the ability to grip or presence of any hand tremor may be a contraindication), clinical results including position of any scotoma(ta) and most importantly motivation. •

Dr Joy Myint is an optometrist and programme lead at the University of Hertfordshire.

In the next article we will discuss dedicated apps for the visually impaired.

References

- www.disabilityrightsuk.org/access-work

- Bambrick R, Dickinson C, Taylor J and Harper R. Prescribing magnification using optical and electronic magnifiers. Optician, 28.04.2017, pp 22-29.

- Taylor J, Bambrick R, Brand A, et al (2017) Comparing portable electronic vision enhancement systems (p-EVES) to optical magnifiers for performance of near vision activities: Results of a randomised crossover trial Ophthalmic Physiological Optics.

- UK Vision Strategy (2014) Outcome 2 Available at: www.vision2020uk.org.uk/UKVisionstrategy/page.asp?section=288§ionTitle=Outcome+2