The need to provide appropriate healthcare support for people living with dementia has become more apparent as our population age rises, with more than 850,000 people in the UK currently diagnosed with a form of dementia.1 There is also a shift in emphasis away from the perception that dementia only affects people in the later stages of life.

Dementia has been called the greatest global challenge for social care in the 21st century

There are currently an estimated 42,325 people in the UK diagnosed with young onset dementia.2 This re-evaluation of dementia is important to consider, and not just from the perspective of those working in the care and medical professions who will increasingly be coming across people living with dementia. It is also important for businesses and employers who will need to accommodate the likelihood that their employees may develop dementia before retirement age.

In a recent commission, The Lancet stated that ‘Dementia is the greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st century’ and stressed that the responsibility of preventing dementia and improving the quality of life for carers lies with us all.3 Charities such as Alzheimer’s Society, Age UK and Mind are stressing the importance of wellbeing and trying to change the stigma surrounding dementia.

What is dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term to describe a set of symptoms associated with an ongoing decline of brain functioning. Memory loss is the symptom most commonly associated with dementia however it isn’t always the first or more prominent symptom, other symptoms include:

- Communication difficulties

- Disorientation of time

- Disorientation of place and person

- Mood swings

- Apathy and depression

- Lack of coordination or balance

- Visual perceptual difficulties and hallucinations

There is always a downward decline with dementia and it progresses at different rates for each individual. The two most common types of dementia are Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, but there are numerous other types of dementia such as dementia with Lewy Bodies, caused by tiny spherical protein deposits in the brain, or frontotemporal dementia, which tends to occur at a younger age, generally between the ages of 40 and 45, and which effects the part of the brain associated with empathy and executive function.

Some issues associated with dementia can be rectified by proper eye care

Although all forms of dementia exhibit similar symptoms, they often follow different patterns of decline. For example, with Alzheimer’s the decline tends to be a steady downhill slope, whereas with vascular dementia you might not notice any changes in someone for some time and then there will be a sudden deterioration in mood or behaviour caused by a minor stroke. This is often described as a staircase pattern of decline.

There is no known cure for dementia, but there is medication that can be taken by Alzheimer’s patients to help with memory loss and confusion as well as improve concentration, motivation, and help with aspects of daily living such as cooking or shopping. A person with mild or moderate dementia might be prescribed an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI), most commonly donepezil, and memantine may be prescribed for people with mid-stage disease who cannot take AChEIs, and for people with advanced dementia or mixed dementia (most typically a mixture of Alzheimer’s and vascular, but this can also be other variations).4

What does this mean for eye care practitioners?

There are currently 250,000 people living with dementia and sight loss in the UK and a recent study carried out by the College of Optometrists found ‘the prevalence of sight loss in people with dementia is higher than the overall population, and almost 50% of those with sight loss were no longer classified as visually impaired when wearing the correctly prescribed glasses’.5 The RNIB encourages people with dementia to get regular eye checks because common side effects of dementia can be alleviated by low vision aids. Often symptoms of dementia, such as problems with balance or visual perception issues, are dismissed as dementia when they are actually caused by sight loss or treatable visual issues. Loss of vision causes someone with dementia to lose confidence in moving around spaces safely and often prevents them from carrying out familiar activities. Accommodating for both dementia and sight loss can be harder than living with either condition on its own and causes the ‘loss of independence, increased confusion and disorientation’ and ‘people with both conditions are also at a heightened risk of anxiety, depression, communication difficulties, low self-esteem, sleep disturbance and social isolation’.6 The chances of developing dementia and the speed in which symptoms of dementia progress is exacerbated by social isolation.7 It is therefore vital that we as professionals make every moment count, because the trip to the optician might be the only social interaction your elderly patient will have that week.

Obstacles facing eye care professionals when treating dementia patients

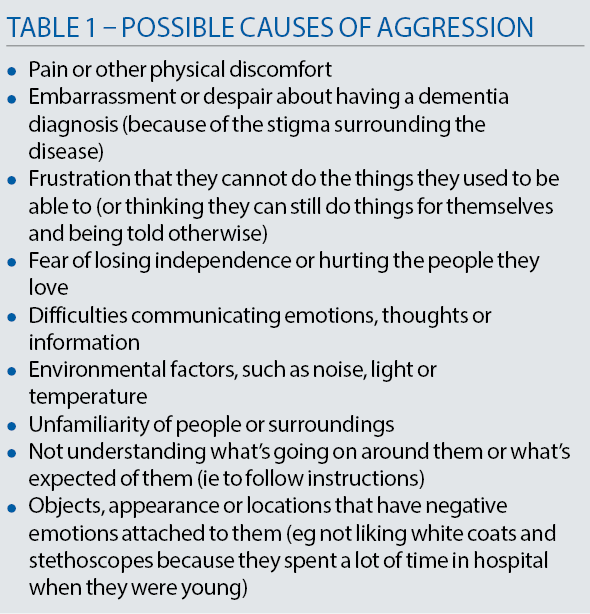

Aggression and communication difficulties are some of the biggest difficulties facing eye care practitioners when treating someone with dementia. It is important to identify probable causes of these behaviours in order to make sure patients can get the appropriate treatment. Table 1 outlines possible causes of aggression

Some symptoms, most commonly aggression, but also hallucination and symptoms caused by low vision, are often incorrectly ascribed to dementia. There is a persistent ideology that dementia causes aggression, or that there is a form of dementia that causes violent behaviour, but in most cases the aggression is caused by social factors (there are some exceptions, of course). These social factors are wide and varied, and it is often the job of a family member, carer or healthcare professional to detect the cause of the problem. Aggression in dementia patients is usually caused by external factors such as temperature, noise or pain and should be taking as indicators of physical or psychological distress. Someone with dementia may not be able to locate the cause of their discomfit or might struggle to communicate that they are experiencing pain or confusion.

Better communication and person-centred care

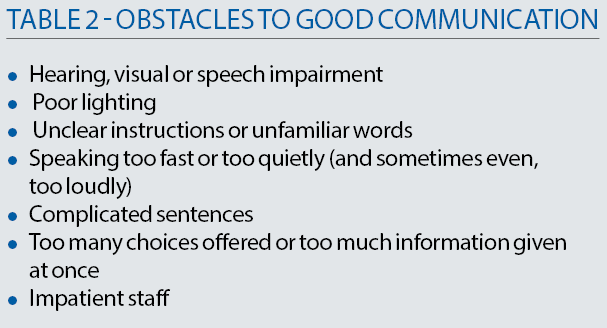

The first means of improving communication with dementia patients is to limit any environmental factors that could cause distress. Someone with dementia can find background noise, like televisions, radios or chatter, very distressing. Find a quiet well-lit place to carry out assessments, minimising outside distractions wherever possible. Try to make the environment as dementia friendly as possible, this may include making small changes to your consultation rooms. These changes may include using contrasting colours, so that the chairs are distinguishable from the floor, and avoid heavily patterned or shiny surfaces wherever possible because someone with dementia may have difficulties seeing things in three dimensions. Someone with dementia may refuse or avoid entering a room because they think the floor looks wet or because to them it looks like there is a large hole in the ground. In a room with heavily patterned flooring, someone with a dementia would be more prone to falls because the floor looks like it is covered in objects and they may lean down to pick them up. Poor vision and issues with 3D perception can account for paranoia or delusions experienced by the patient, especially in poorly lit rooms.Table 2 summarises possible obstacles to good communication.

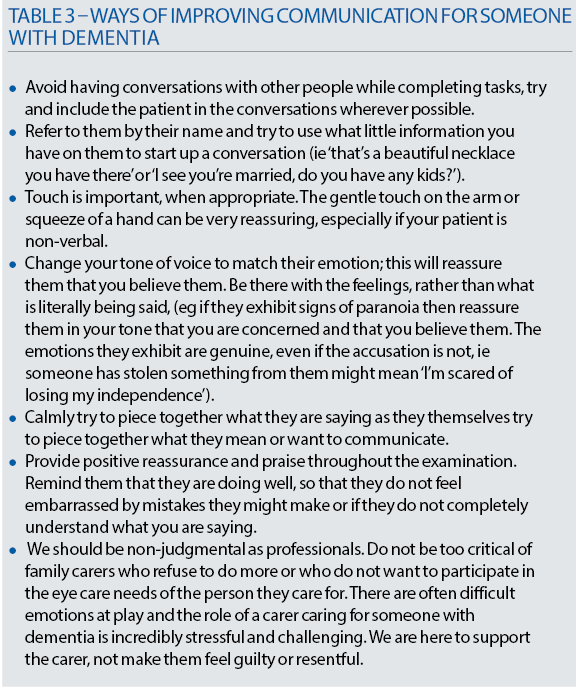

It is also useful for eye care practitioners to adapt their speech and body language to be more accommodating to someone with dementia. Improved communication and person-centred care largely involves ‘considering what the person with dementia understands, is trying to say, and what they want, rather than being focused on completing a task […] It involves verbal and non-verbal communication’.8

Using a calm tone, maintaining eye contact and smiling are all very reassuring, especially if the patient is scared or confused. Try breaking down tasks or explanations into short, clear and simple instructions, and avoid giving too many choices at once. Take the time to repeat or simplify what you have already said and be patient, this will save you more time in the long run because you will avoid challenging behaviours. Sometimes people with dementia have difficulty relating words to objects and it can help showing them the object you are talking about, for example when asking them ‘would you like a drink?’ do so while showing them a mug or glass.

Use a calm tone and maintain eye contact

Reminiscence is one of the best tools we have for communicating with someone with dementia. Short-term memory is impaired in dementia patients, but long-term memory remains very acute for a long time, and when speaking with someone with dementia we often have to enter their timeline and reality. Someone with dementia may keep losing or refuse to wear their new glasses because they do not recognise them. It might be better, where possible, to fit old frames with new lenses or help carers choose new frames that are as similar to the patient’s old glasses as possible.

It might be helpful using older terminology or equipment that resembles older models, or using objects or language that is more familiar to them. Try to use what little information you might have about the person with dementia to encourage them to open up and talk about themselves. This will make them calmer and therefore make it easier to test their eyes, but also enables this brief eye examination to be a meaningful interaction. One of the treatments currently used by memory doctors is Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST), which uses reminiscence, games and activities and group social interaction to stimulate brain activity and thus help slow down further cognitive decline.9 If appropriately utilised, even the shortest eye examinations can have positive results for dementia patients, or elderly patients who are more at risk of developing dementia. Studies have shown social engagement can be an important mechanism for improving the quality of life among people with dementia.10

Simple steps can improve communication with dementia sufferers

If there is a carer present, then utilise their knowledge of the patient and work with them to ensure their loved one is calm and comfortable. Family carers ‘are the most important resource available for people with dementia’ and consequently for healthcare professionals.11 Use their knowledge and experience to communicate effectively with your patient. However, do not leave the person with dementia out of the conversation, do not ignore them while talking to the carer and always include them in decisions about their care wherever possible. Avoid situations where the carer might be contradicting the patient (‘yes – I have been putting my eye drops in every day’), if this situation occurs try to provide the opportunity to speak briefly with the carer in private. Table 3 summarises the various approaches to improving communication with a dementia patient.

What help is there available?

Currently there is not a national organisation for dementia but most local boroughs will have services or charities who can support both people living with dementia and their carers. If your patients exhibit any of the symptoms of dementia previously described, the procedure is to refer them to their GP who will do an initial cognitive assessment. There are several different tests but the most common one used by GPs is the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) or the Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS). Based off the test scores the GP will refer them to the local Memory Service for further cognitive assessments and brain scans. Once the diagnosis is in place they can access more support services, these vary from borough to borough. Some London boroughs have established dementia hubs, which are information and signposting services and can answer most of your dementia related questions (check out the Bromley Dementia Support Hub). There is also a lot of resources online, Alzheimer’s Society has a whole of wealth of information fact sheets and leaflets on dementia, varying from ‘Understanding and supporting a person with dementia (524)’ to ‘Sight, perception and hallucinations in dementia (527)’. These fact sheets are useful for anyone who wants to know more about dementia and are not restricted to dementia patients. •

Tallulah Harvey is a liaison officer with the mental health charity MIND and is involved in linking people with dementia with healthcare professionals.

References

- ‘Facts for the Media’, Alzheimer’s Society, https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/news-and-media/facts-media

- (Ref Dementia UK, 2nd edition 2014, Alzheimer’s Society), https://www.youngdementiauk.org/sites/default/files/Dementia_UK_Second_edition_-_Overview.pdf

- ‘Dementia prevention, intervention, and care’. The Lancet Commissions. Published online July 20, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6, pp. 1, 46

- ‘Dementia prevention, intervention, and care’. The Lancet Commissions. Published online July 20, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6, pp. 22-25

- ‘Dementia and sight loss: promoting good eye health’, RNIB. http://www.rnib.org.uk/professionals-social-care-professionals-complex-needs-social-care/dementia-and-sight-loss

- The Journal of Dementia Care. ’Dementia and sight loss: a challenging combination’ (pp. 26-7) Paul Ursell; Gemma Jolly ( Vol 25 No 5 September/October 2017), p. 26-7.

- Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Oude Voshaar RC, et al, ‘Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev 2015; 22: pp. 39-57

- ‘Dementia prevention, intervention, and care’. The Lancet Commissions. Published online July 20, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6, p.31

- Spector A, Thorgrimsen L, Woods B, et al. ‘Efficacy of an evidence-based cognitive stimulation therapy programme for people with dementia: randomised controlled trial’. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183: pp. 248-54

- ‘Dementia prevention, intervention, and care’. The Lancet Commissions. Published online July 20, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6, p.31

- ‘Dementia prevention, intervention, and care’. The Lancet Commissions. Published online July 20, 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6, p. 37