From physical harm to sexual or emotional exploitation and neglect of basic needs, abuse can embrace various forms. These types of maltreatments are particularly repulsive when they involve children or elderly that are less inclined to stand-up for themselves. These individuals usually end up in the emergency units and are seen and cared for by multidisciplinary medical teams. Nevertheless, optometrists and ophthalmologists could also spot, for the first time, ocular problems resulted from the so-called ‘non-accidental injuries’ (NAI) and their proper intervention and referral might save the life of the affected individual.

Child abuse

Physical harm is one of the most dangerous forms of child abuse and it has been reported that up to 80% of deaths from head trauma in infants result from violence in the family (American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect). Signs of physical abuse can be seen on various parts of the body and are represented by a large variety of injuries, from bruises, burns, bites, fractures, open wounds, haemorrhages and so on. The child’s behaviour is also affected. These children usually show signs of anxiety, aggression, look depressed, are uncomfortable with physical contact and look frightened in the company of adults. In addition, they also display abnormal speech, have short attention span and can look tired.

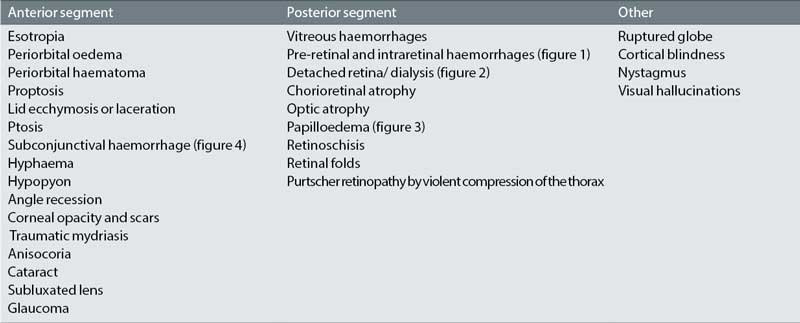

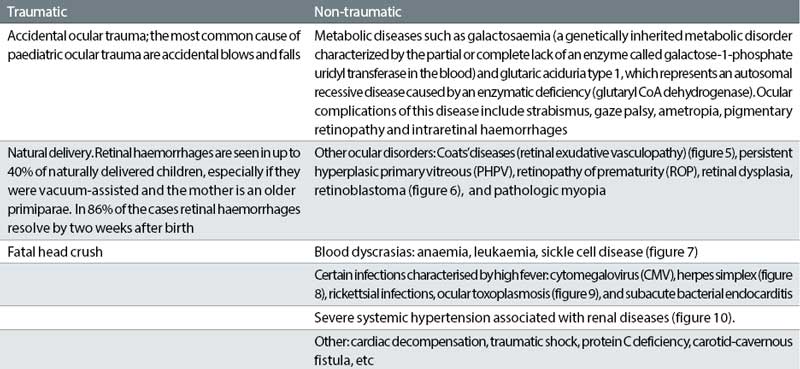

Figure 1: Pre-retinal and intraretinal haemorrhages

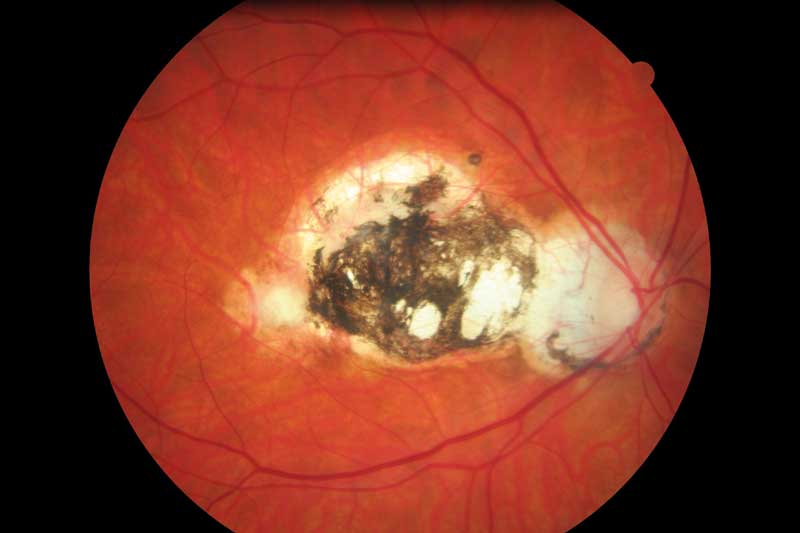

For optometrists, ocular signs of child abuse are particularly important to spot (table 1).1

Table 1: Ocular signs of abuse in children

Below are discussed two of the most common types of physical abuse in children.

Paediatric Abusive Head Trauma (AHT)

Paediatric AHT is a condition that results from shaking, blunt impact, suffocation, strangulation, dropping and throwing a child and leads to various neurological injuries in a baby or child less than 5 years old.2 Another term, ‘shaken baby syndrome’ (SBS) is also used to describe brain injury symptoms consistent with vigorously shaking an infant or small child, less than two years old. However, SBS-like injuries, can also be observed in older children. The exact mechanism producing the intracranial injuries in SBS is thought to be the ‘whiplash’ type movement of the head on the neck during manual shaking. The anatomical features of infants, which include a relatively heavy head, weak neck muscles as well as an immature, unmyelinated brain and open fontanelles, contribute to the degree of cerebral tissue injuries during violent shaking. Cerebral damage in SBS can also result from a combination between shaking and head impact. The child presents with symptoms such as high-pitched cry (in infants), irritability, tremors or convulsions, failure to thrive, red and watery eyes, fatigue, localised tenderness, stuffy nose, lethargy, sweating and coughs. Occasionally they present with earache, vomiting and diarrhoea.

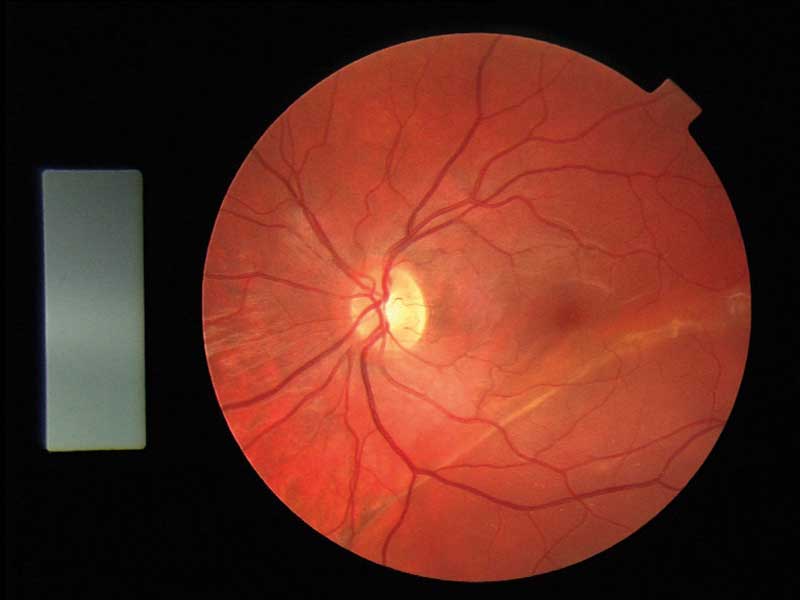

Figure 2: Detached retina/dialysis

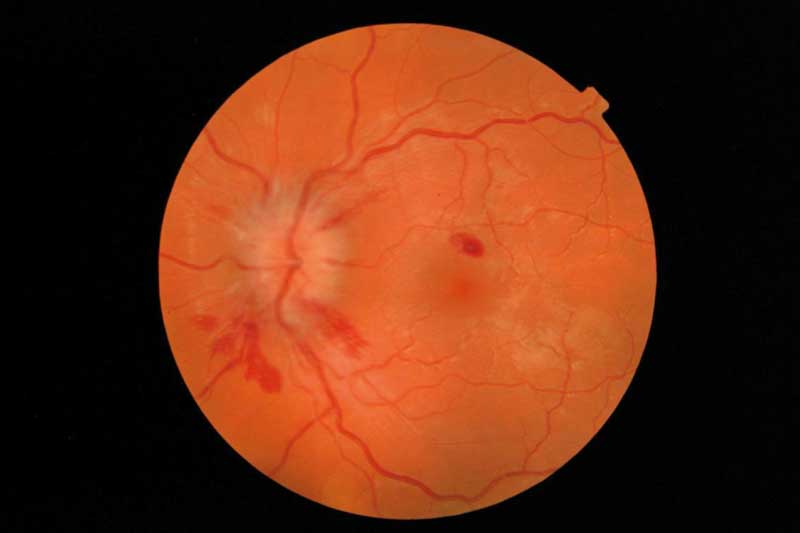

Ocular injuries are present in approximately 70% of SBS children. The triad of SBS refers to encephalopathy with a subdural haematoma and retinal haemorrhage. Retinal haemorrhages occur in 50 to 80% of cases3 and vary in size, shape and severity. They are most often flame-shaped, extensive and can obscure other retinal structures. Vitreous and retinal haemorrhages can be the direct result of acute intracranial hypertension but can also occur following venous transmission to the eye of intrathoracic forces and direct head trauma.

Other possible ocular lesions such as circular perimacular retinal folds and peripheral retinoschisis as well as lack of visual response to stimuli following trauma have been found to correlate with a fatal outcome.4 Visual loss in SBS is due to retinal damage, optic atrophy and damage of the visual cortex. Amblyopia, due to visual deprivation by vitreous haemorrhage may also occur.

Figure 3: Papilloedema

SBS victims are difficult to diagnose for several reasons:

- They present with non-specific symptoms that can be attributed to other general illnesses.

- External signs are often subtle.

- The parents hide the history of injury.

- These children are often seen by non-ophthalmic medical personnel who usually do not examine the retina for retinal haemorrhages.

In addition, a diagnosis of inflicted head injury cannot be performed only on the finding of retinal haemorrhage alone. Indeed, other situations can also result in retinal haemorrhages (table 2). Nevertheless, the type and distribution of these haemorrhages are different. The association of severe bilateral flame-shaped haemorrhage and a parental explanation of accidental head injury, however, is suggestive of SBS.3

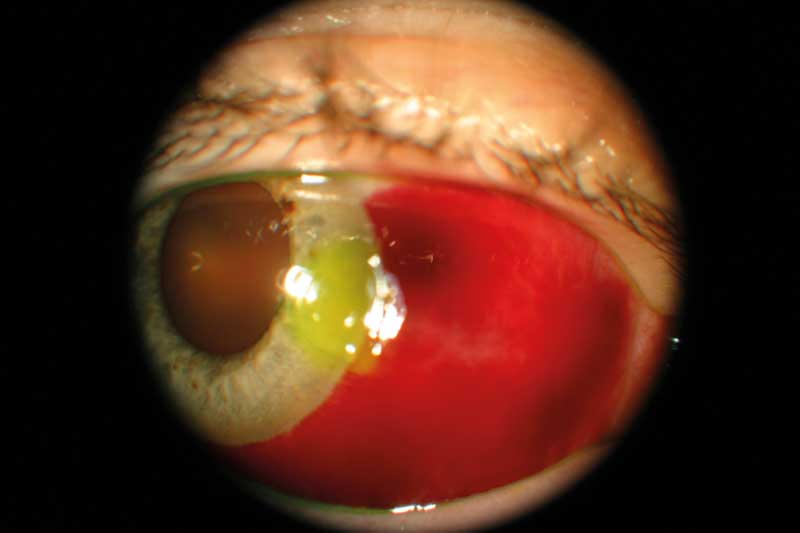

Figure 4: Subconjunctival haemorrhage

Fabricated or Induced Illness by Carers (FII)

Fabricated or Induced Illness by Carers (FII) is a term adopted in 2002 by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) to replace the older term of Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy (MSbP), introduced in 1970. FII is not a physical harm per se only but represents a ‘continuum of parental health-care seeking for a child, which ranges from extreme neglect (failure to seek medical care for the child) to induced illness’ , in a context of an abnormal relationship with health and social-care providers, with an adverse effect on the child.5 The incidence of FII in the UK and Republic of Ireland is estimated to be 0.5-2.8/100,000 children under 16 years of age although the vast majority of cases are usually four years of age or under.

Table 2: Other situations that could result in retinal haemorrhages in a child

FII can include exaggeration or misconstruction of events, false reporting, falsification of records, interference with medical investigations and inducing illness in a child (poisoning, overmedication, suffocation, starvation, etc). In more 50% of cases, the parent or caregiver suffers from a personality disorder or from a factitious disorder themselves. It is believed that some explanation for this type of behaviour in a parent could be provided by the existence of extreme anxiety, wish for attention, deflection of blame and material gain.5 This condition is usually identified by paediatricians but needs to be managed using an interdisciplinary approach.

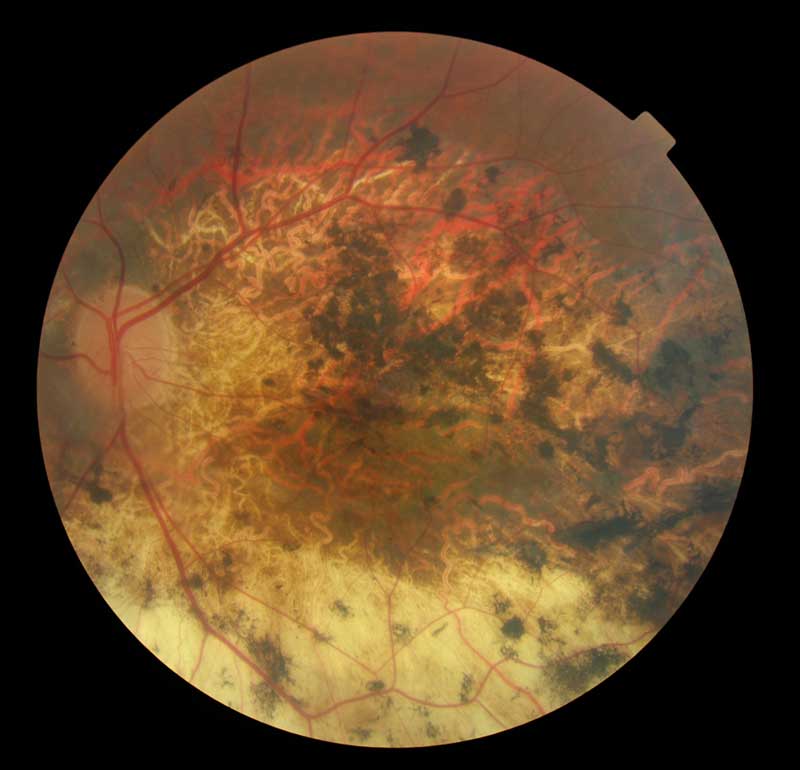

Figure 5: Coats’ diseases (retinal exudative vasculopathy)

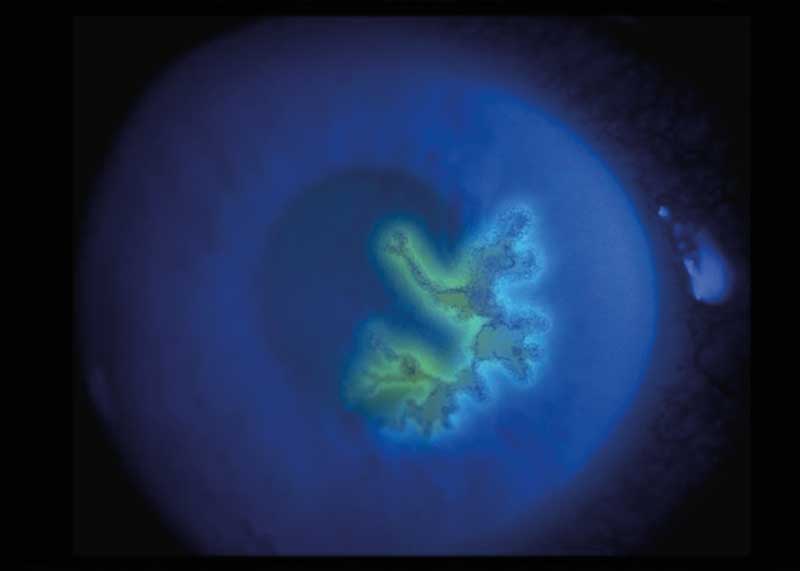

Figure 6: Retinoblastoma

Ocular conditions that can be ‘fabricated’ are rare, but possible. In a case report published in 2016, Valeina et al reported various ophthalmic findings associated with retardation, somnolence and seizure in two siblings from the age of six months to 12 years.6 After comprehensive evaluation, all other potential causes have been eliminated and FII was established. Nevertheless, this kind of diagnosis by eliminations can take a very long time and this goes against the well-being of the child. Recurrent conjunctivitis (figure 11) has also been reported in such cases and FII should be included in the differential diagnosis of these conditions in children whenever a possible physical explanation cannot be found.7

Figure 7: Sickle cell disease

Figure 8: Herpes simplex

Evaluation and attitude

In general, consultation in the case of physical child abuse should involve the presence of an interdisciplinary team composed of a paediatrician, orthopaedic surgeon, ophthalmologist, geneticist and child mental health specialist. A detailed history is very important and although the story offered by caregivers is often misleading, an intelligent investigation and a careful examination are invaluable for a positive diagnosis. Wherever possible, the child and the caregivers should be questioned separately.

The doctors should document:

- The date, time and place of the injury.

- Who was present when the injury occurred.

- The measures that caregiver has taken after the injury.

- If the caregiver presented immediately with the child to the doctor.

Physical examination of the child is extremely important. In critically injured children, however, physical examination is performed in conjunction with first aid measures. It is vital that photographs are taken as soon as the child arrives in the hospital and these should be preserved with care. The physical and psychological status of the child should also be considered (see above). Ophthalmological consultation should be performed in all cases of suspected child abuse and the doctor should note and document any ocular injury. The finding of bilateral retinal haemorrhages requires a head CT for the existence of subdural haematoma.

Figure 9: Ocular toxoplasmosis

Figure 10: Severe systemic hypertension associated with renal diseases

In 2017, the Optical Confederation published the updated ‘Guidance on Safeguarding, Mental Capacity and the Prevent Strategy’ that provides a simple five steps for optometrists and opticians to safeguard children and vulnerable adults in the line with the current legislation. Guidance on responsibilities,

working in partnership and referral are also provided. It is recommended that these guidance is available to all practices and practitioners should ensure that they complete appropriate recommended training in line with the Level 2 in the Intercollegiate Safeguarding Guidance (2014).8 Based on their recommendations, in case of suspicion of abuse, the practitioners should:

- Observe factual signs and symptoms.

- Discuss with the manager or local authority safeguarding team.

- Act to inform the local authority safeguarding team.

- Confirm notifications .

- Record all observations.

Figure 11: Conjunctivitis

The RCPCH as well as the HM Government also have produced materials on safeguarding children in whom illness is fabricated or induced.9,10 Safeguarding these children entails joint responsibility of children’s social care services and the police and usually results in proceedings to establish whether the abusing parent should continue to care for the child. Criminal prosecutions are also possible. Therefore, suspicion of FII caries heavy responsibilities. Nevertheless, in case of strong suspicion, appropriate reporting before the child comes to serious harm, is extremely important and should follow the above guidelines.

Elder physical abuse

It has been reported that 10% of people aged 65 and over are experiencing some kind of abuse (Action on Elder Abuse, 2017). However, many other cases go unreported. Indeed, although some individuals will complain of mistreatment, most will only exhibit signs of trauma, poor hygiene, malnutrition or dehydration.11 Maltreatment in elderly can exhibit various forms, from physical harm, psychological abuse, sexual assault, material exploitation and neglect.11

Figure 12: Falling injuries are common in the elderly but could it indicate abuse?

Searching for ophthalmic literature reporting physical abuse in the elderly, triggered very few results indeed. The reason behind this is unclear. Many of the physical signs of abuse can be attributed to falls, knowing that fall hazard is high in this age group (figure 12). Nevertheless, facial and eyelids bruises and lacerations, conjunctival haemorrhages, corneal trauma or even ectopia lentis12 that cannot be explained by other causes should be regarded as highly suspicious of abuse, especially in the context of a withdrawn, malnourished and anxious elderly individual with multiple bruises and with a caregiver that is, most of the time, financially dependent on the victim or is institutionalised.

Conclusion

The optometrist should always put the interest of the patient above all other interests. Sometimes is easier to just address the ocular complaint and ignore the rest. However, as health care providers, the role of the optometrist is crucial in insuring the general well-being of their patients. They should work as part of the patients’ care teams with the patients’ needs at the core of their practice. By doing this, the professional optometrists can play a role not only in detection and management of ocular condition but also in prevention and intervention in more general pathological and even social issues that affect each individual patient. A proper diagnosis and referral could secure the future and the life of children and other vulnerable individuals abused or at risk of being abused. Optometrists are the ‘gatekeepers’ for their patients and although they cannot directly act when maltreatment is suspected, they can alert other specialists, help social workers and ensure that the proper care is given to the affected individual.

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

References

- Smith SK. Child abuse and neglect: a diagnostic guide for optometrist. J Am Optom Assoc 1988; 59: 760-766

- Joyce T, Huecker MR. Pediatric abusive head trauma (Shaken Baby syndrome). StatPearls. Treasure island (FL); StatPearls Publishing 2018, may 15

- Togioka BM, Arnold MA, Bathurst MA et al. Retinal hemorrhages and shaken baby syndrome: an evidence-based review. J Emerg Med 2009; 37: 98-106

- Mills M. Fundoscopic lesions associated with mortality in shaken baby syndrome. J AAPOS 1998; 2: 67-71

- Bass C, Glaser D. Early recognition and management of fabricated or induced illness in children. Lancet 2014; 383; 1412-1421

- Valeina S, Krumina Z, Sepetiene S et al. Fabricated or induced illness presenting as recurrent corneal lesions, cataract and uveitis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2016; 4; 53

- Baskin DE. Stein F, Coats DK, Paysse EA. Recurrent conjunctivitis as a presentation of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Ophthalmology 2003; 110; 1582-1584

- Optical Confederation. Guidance on safeguarding, mental capacity and the prevent strategy. Protecting children and vulnerable adults. Updated June 2017. http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/oc-safeguarding-guidance – updated – june-2017.pdf

- Child Protection Companion (2nd edn), Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, London (2013)

- HM Government: Safeguarding children in whom illness is fabricated or induced: supplementary guidance to Working Together to Safeguard Children, Department for Education, London (2008)

- Lachs ES, Pillemer K. Elder abuse. Lancet 2004; 364: 1263-1272

- Scothorn DM, Sporn A, Terry JE. Ectopia lentis secondary to physical abuse in traumatized, elderly patient. J Am Optom Assoc 1991; 62; 630-633