Eye care professionals are at the forefront of their patients’ ocular but also general healthcare. They can make a difference in so many ways, from improving vision to detecting ocular and systemic pathologies and even increasing the wellbeing of patients and their families. But nothing makes a more dramatic impact than saving a patient’s life if the situation arises. Our patients often suffer from diseases that, in their acute form, could threaten their life. Such acute events could occur any time and the eye care professional could face a situation when their quick response is the only way to save the patient before other help arrives. This article will present few of the most common medical emergencies that could occur in the optometrists’ consulting rooms, or indeed anywhere throughout the practice. These situations are presented in no particular order.

Heart angina and heart attack

Heart angina and heart attack are two manifestations of cardiovascular disease (CVD), a group of disorders in which the blood vessels throughout the body are blocked by high levels of cholesterol depositions, blood clots or combinations and, therefore, the blood supply to tissues and organs is impaired, leading to ischaemia and cellular death. It is important to note that although most of the patients suffering from these diseases are known to the medical profession and already under specific treatment, it is possible that in others, these acute manifestations of the CVD are the first presentation of the disease.

In case of heart angina, the patient will complain of constricting chest pain, more simply described like pressure, squeezing or crushing pain that can radiate to the neck, left arm or back. The patient is generally unwell and feels dizzy. In angina, the attack usually resolves within 10 minutes and the patients have a history of such episodes, so they carry glyceryl trinitrate medication (GTN tablets or spray) that they can use as soon as the symptoms occur. The eye care professional should help the patients with their medication, help keep calm and call the emergency services if the attack does not resolve in 10 minutes or the symptoms aggravate. Heart angina should be differentiated from more benign situations such as intercostal neuralgias (burning, sharp localised pain of the rib cage), muscle strain, heartburn, chest infections or even panic attacks.

In a heart attack, the chest pain is associated with additional symptoms such as shortness of breath, nausea, cold sweat, dizziness, fast and irregular pulse, numbness in the arms and shock. In some situations, a heart attack does not present with chest pain but with signs of acute abdominal pain and can be mistaken for diseases of the digestive system. Nevertheless, the patient’s history can help with a rapid differential diagnosis.

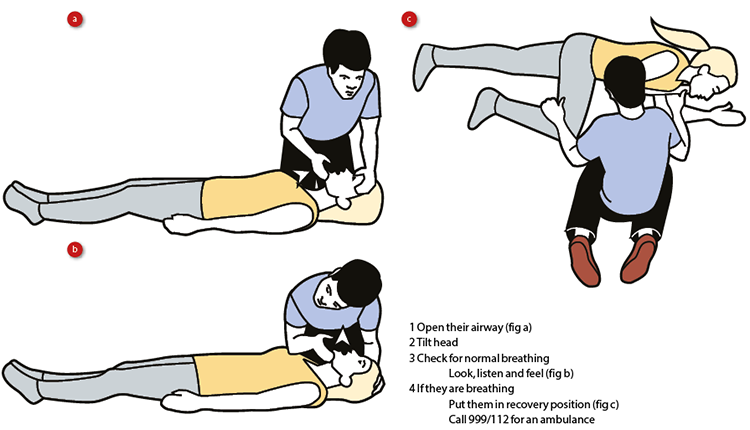

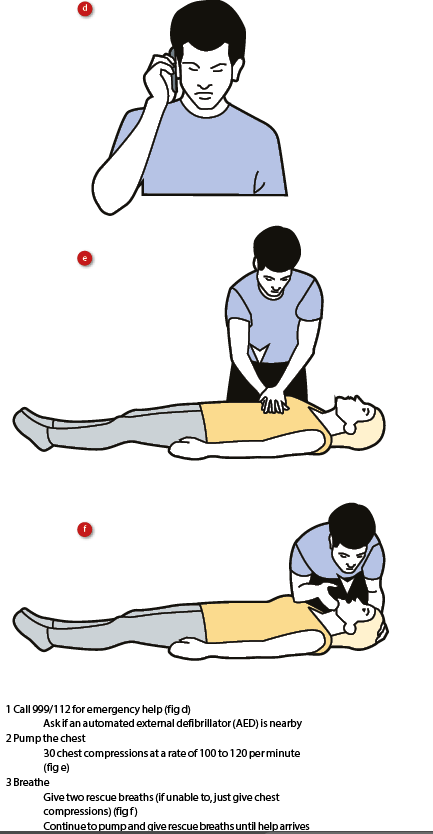

In case of suspicion of a heart attack, immediate call for the emergency services is necessary. If the patient goes into cardiac arrest before the ambulance arrives, it is important to administer resuscitation (see figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: First aid for a non-responsive patient still breathing

Stroke

A detailed description of the role of the eye care practitioner before, during and after stroke was provided in a recent issue of this journal (Optician 19.05.17). It is important to remember that, during a stroke, the patient can exhibit various symptoms, such as weakness or paralysis on one side of the body (face, arm, leg), slurred speech, confusion, loss of balance, tingling, burning or numbness of the skin, headache and vision loss.

The eye care professional should remember to recognise and respond to stroke as eFAST:

- Eyes: In stroke, there could be conjugate ocular deviations towards the affected hemisphere of the brain.

- Face: Ask the patient to smile and assess the asymmetry of the face. In case of a stroke, one side of the face is drooping or feels numb, therefore the smile appears uneven.

- Arms: Ask the patient to raise both arms and observe weakness. One side of the body is usually affected and the patient cannot move the arm on that side.

- Speech: Slurred speech when trying to answer questions or when asked to repeat a simple phrase.

- Time: Call 999 immediately if any of the above occur.

It is important to remember that each patient is affected differently by stroke and only one or a couple of the changes described above can appear evident at the initial inspection. In addition, there are other signs and symptoms that may point towards development of a stroke, including:

- severe headache

- loss of balance

- blurred vision

- memory loss

- behavioural changes

- muscle stiffness

- difficulty swallowing

By being able to recognise even the most subtle of changes and by acting eFAST, the eye care professional can offer help immediately and contribute to saving the life of the patient.

Diabetic acute hyper- and hypoglycaemia

Optometrists play an important role in the diagnosis, follow-up and referral of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetics of all stages of the disease are therefore common attendees within optometric practice. However, retinopathy is only one complication of diabetes, a very complex systemic disorder that affects all the organs and the systems of the human body. Eye care professionals are part of the diabetic patients’ health care teams and they should recognise and act when other complications occur, especially in their acute form. Two of such complications, that can put the patient’s life in danger, are hyper- and hypoglycaemia.

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) occurs when the level of blood glucose is too high due to insufficient insulin. This complication can be triggered by various factors, including infections, stress as well as a missed insulin dose or insufficient insulin administration associated with a high caloric intake. Patients suffering from DKA present with acute shifts in refractive errors, dehydration, abdominal pain and vomiting. They have a high urgency to urinate frequently, breath very fast, feel tired and confused and can also pass out. A very characteristic feature of patients with DKA is their breath that has a strong fruity smell, easily recognisable.

These patients need prompt recognition of their symptoms and intervention. The patient is usually a known diabetic with possible history of similar episodes. The emergency services should be called in and the condition is treated at the hospital with insulin, fluids and electrolytes perfusions.

Hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia is the most common and potentially, the most dangerous acute diabetic complication being fatal in more than few occasions. It occurs if there is not enough sugar in the bloodstream to counteract high levels of insulin. Situations that can lead to this imbalance are skipping meals while injecting a full dose of insulin, alcohol consumption, infections treated with antibiotics as well as treatments with antidepressants and beta-blockers, all medications that enhance the action of insulin.1

Symptoms of hypoglycaemia are:

- dizziness

- change in behaviour (anxiety, irritability)

- hunger

- sweating

- headache

- confusion

- difficulty speaking

- visual disturbances.

If it is untreated immediately, the patient can have a seizure and become unconscious.

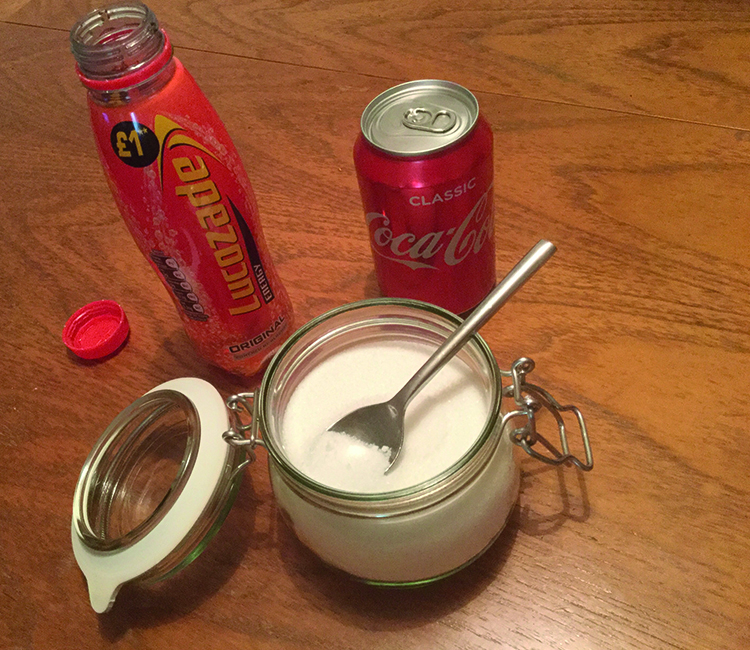

Diabetic patients are used to having various hypoglycaemic episodes and usually carry with them a source of glucose (sweets, juice) that they can access in case of such an event. Nevertheless, when dealing with acute hypoglycaemia the NICE guidelines state to give 10g-20g of glucose (two to four teaspoons of sugar or three to six sugar lumps) or 110mL Lucozade or 100mL Coca-Cola and repeat if necessary after 10-15 minutes (figure 3).

Figure 3: Initial emergency treatment for hypoglycaemia according to NICE guidelines (two to four teaspoons of sugar or 110mL of Lucozade or 100mL of Coca-Cola, repeated as necessary

After this initial treatment, the patient should have a snack (eg a sandwich, fruit, milk, or biscuits) or a full meal (if it is due). If the patient falls unconscious, they should be lain with their feet higher than the heart to facilitate circulation towards the brain and the emergency services called immediately. In this case, the patients will need immediate intravenous treatment with

glucose.

Syncope and seizures

Syncope is the term used to describe an episode of loss of consciousness caused by a reduction in blood flow to the brain due to pre-existing cardiovascular disease, stress, extreme pain, acute loss of blood, panic attacks or prolonged standing that, in predisposed individuals, could result in a drop in blood pressure. Before fainting, the patient will look pale and feel unwell, light headed, nauseous and will complain of blurred vision. The blood pressure will be low (a 30 mmHg or more drop in the systolic blood pressure) and the pulse is high. Without help, the patient will lose consciousness. In real syncope, the consciousness is regained in couple of minutes but the patient will still feel confused and anxious for a short while.

The eye care professional should help the patient lie down, in a safe position to minimise risk of injury and keep the patient hydrated. The legs should be elevated above the heart level to facilitate brain perfusion with blood. In addition, neckties and shirts should be loosened up around the neck.

These patients should be referred to their GP for a complete evaluation of their health. In certain conditions, when the patient complains of diplopia, dizziness and occipital headaches, a basilar artery insufficiency can be suspected and the patient should also be evaluated for risk of stroke.2

Syncope should be differentiated from seizures, especially those episodes associated with convulsions. However, post syncope, the patients will recover faster and their confusion state does not last long, as opposed to seizures.

Seizures represent episodes of lost consciousness associated with convulsions due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Repeated episodes of seizures constitute epilepsy, a complex spectrum of disorders with different causes and manifestations. Seizures are caused by various neurologic disorders, hypoglycaemia, drugs, head trauma, brain infections (meningitis), brain tumours or eclampsia.

The appropriate response to seizures is similar to that in a case of syncope. If the patient does not regain consciousness, the emergency services should be called in.

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a severe allergic reaction presenting with urticaria (hives), angioedema (swelling of the skin), bronchospasm (constriction of the air tubes) and cardiovascular instability. It can affect one in 1,000 of the general population (according to recent statistics from Allergy UK).

It occurs just minutes after allergen exposure and, when there is respiratory distress and vascular collapse, death can occur so it is a life-threatening condition. Anaphylaxis is usually triggered by allergens such as food (typically peanuts and shellfish, though people may be sensitised to many others), insect venom and some medications.

Usually, the patient has a history of allergic reactions and presents with symptoms that may include:

- swelling of the tongue and throat

- difficulty swallowing and speaking

- wheezing or difficulty breathing

- abdominal pain

- vomiting

- dizziness

- collapse

- loss of consciousness

Although rare, it is possible for anaphylaxis to occur after instillation of eye drops. Indeed, anaphylaxis after instillation of polymyxin B-trimethoprim drops,3 fluorescein staining,4 cyclopentolate,5 eye-drops containing benzalkonium chloride preservative, and even hydroxypropyl methylcellulose during cataract surgery6 have all been reported. Nevertheless, even if extremely rare, it can occur. Therefore, a good medical and drug history should be taken from all patients before the administration of any eye drop and this should be clearly recorded as having been undertaken. Particular attention should be paid in patients with multiple food and drug allergies. Patients with previous anaphylaxis episodes should be monitored very close after instilling any drop.

If anaphylaxis occurs, all eye care professionals should be able to recognise immediately its symptoms because death can occur in a few minutes. The first line of treatment in anaphylaxis is adrenaline given by injection (available in the UK are: Epipen, Emerade or Jext – figure 4). Patients prone to anaphylaxis carry these pens with them at all times. An ambulance should be called immediately and stated that the patient suffers from anaphylaxis.

Figure 4: An Epipen can make the difference between life and death

Conclusion

Although eye care professionals are trained to diagnose and manage most of the existing ocular emergencies, sometimes they find themselves unsure about the first response in case of a medical emergency that occurs in their consulting room. Even before the ambulance arrives, to make the differences between a life lost and a life saved, it is important that certain manoeuvres are administered as soon as possible. Therefore, prompt recognition of symptoms and adequate first aid knowledge is important. NICE states that healthcare organisations (including primary care settings) ‘have an obligation to provide a high quality resuscitation service, and to ensure that staff are trained and updated sufficiently regularly to ensure that they are proficient in resuscitation in relation to their expected role’.7

Eye care professionals, as primary care providers, should be qualified first aiders and facilitate basic first aid in the practice they work for. Appropriate use of a defibrillator and access to one should be known and available for all practices.

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

References

1 Cavallerano JD. The myriad threats of diabetes mellitus. Rev Optom 1994 Oct 15;131(10):93-110.

2 Muchnick BG. Clinical medicine in optometric practice. 2008. Mosby Elsevier

3 Henao MP, Ghaffari G. Anaphylaxis to polymyxin B-trimethoprim eye drops. Ann allergy Asthma Immunol 2016; 116: 372

4 Kaimbo WK. Anaphylactic shock after fluorescein staining corneal abrasion. A case report. Bull Soc Belge Ophthalmol 2011; 317: 29-31

5 Tayman C, Mete E, catal F, Akca H. Anaphylactic reaction due to cyclopentolate in a 4-year old child. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2010; 20: 347-348

6 Munk SJ, Heegaard S, Mosbech H, Garvey LH. Two episodes of anaphylaxis following exposure to hydroxypropyl methylcellulose during cataract surgery. J cataract Refract Surg 2013; 39: 948-951

7 Resuscitation Council (UK). Quality standards for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and training. https://www.resus.org.uk/quality-standards/