This article is based on material to be used in a new course to be launched this coming October. Aston University will be the first optometry department in the UK to launch a course in Geriatric Optometry. For further information and details of how to apply, go to www.aston.ac.uk/lhs/continuing-professional-development/geriatric-optometry-standalone-module.

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) represents a complex disorder with multiple risk factors. In addition, due to the fact that is more common in the elderly, POAG can also co-exist with a large variety of age-related ocular and systemic conditions and this cohabitation has profound effect on disease prognosis both ways as well as on the patients’ wellbeing. Below we will discuss some of these situations.

I Glaucoma and ocular co-morbidities in elderly

1 Ocular surface disease (OSD) and glaucoma

Both dry eye and glaucoma are more common in the geriatric population and when occurring together, they can have a profound effect on each other’s prognosis but also on the patient’s wellbeing. OSD represents a spectrum of disorders from dry eye, meibomian gland dysfunction, rosacea (figure 1), allergies, as well as other anterior eye surface damage caused by chronic use of eye drops.

Figure 1: Ocular surface diseases are more common in the elderly

The presence of OSD is diagnosed based on the characteristic symptoms as well as tests, such as Schirmer, tear osmolarity and tear break-up time (TBUT). Most of the glaucoma drops could have significant side effects on the ocular surface, which can aggravate a pre-existing OSD.1

Indeed, beta-blockers, alpha-2 agonist, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and prostaglandins, can all have various ocular side effects, from redness, burning, itching, to dermatitis, skin pigmentation, and even punctate keratitis.2 These side effects are mostly due to the presence of preservative benzalkonium chloride (BAK).

It has been reported that one in six glaucoma patients have OSD severe enough to require treatment for it.3 The presence of these complications could result in significant decrease in the glaucoma patient wellbeing due to discomfort, this will further impact on compliance to treatment and, therefore, have a negative impact on the patient’s outcome. In addition, due to the associated inflammation, OSD can also impact greatly on the success of glaucoma filtration surgery procedures.

In the glaucoma clinic, specialists are often focused on treating glaucoma itself, especially in difficult cases that progress despite all efforts. Therefore, it can be possible that the presence of OSD in a glaucoma patient with multiple complications and disease progression, is overlooked.

Nevertheless, the possibility of its existence should always be considered, especially in patients with multiple medication. Whenever starting a patient on an antiglaucoma drop, it is necessary to perform a full examination of the ocular surface. Use of preservative-free drops and used fixed combinations of medication for glaucoma to reduce the amount of drops given, should be considered on a case by case basis, paying particular attention in elderly patients with other systemic morbidities or disabilities.

2 Cataract and glaucoma

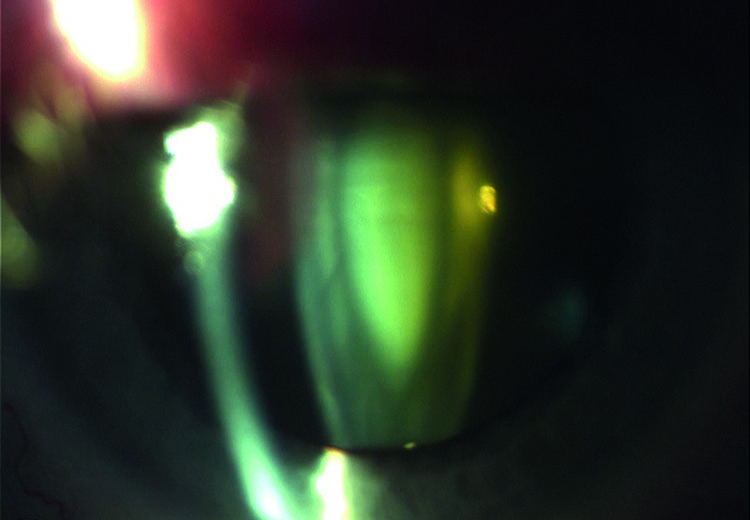

Both cataract (figure 2) and glaucoma are diseases of the old age and, therefore, often co-exist in the elderly. When present, the cataract can affect the diagnosis and follow-up of glaucoma. In addition, cataract surgery has also an effect of the IOP, both immediate post-surgery and also longer term, if complications occur.

Figure 2: Cataract is an age-related problem and common in glaucoma sufferers

Therefore, when a patient has both pathologies, the treatment goals are more complex and involve long-term IOP control, as well as an increased care to preserve optimal visual function and to improve patients’ quality of life.4

Most of the time, these patients are treated using various combined surgical procedures that are beyond the scope of this article. The decision on single or combined procedures is usually based on the target IOP, treatment compliance, side effects of the glaucoma drugs, patients’ background (social, access to treatment), presence of other disabilities and the patients’ quality of life.4

The optometrists should be aware that before surgery, the routine assessments for both glaucoma and cataract should be performed in parallel. In addition, the possible side effects of previous anti-glaucoma drops, as described in the OSD section, should be considered when assessing the possible outcome of the cataract removal procedures.

3 Retinal disorders and glaucoma

It is estimated that more than 15% of POAG patients suffer from a coexisting retinal pathology, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) or diabetic retinopathy (figure 3) (DR).5

Figure 3: Diabetic retinopathy may coexist with glaucoma

POAG and AMD are both disorders associated with irreversible blindness. In addition, they also affect different parts of patients’ vision, making their co-existence even more critical. Indeed, in patients suffering from both conditions, there is a significant increase in the degree of sight loss with its direct consequences on the individual, family and society. In these individuals, depression, social isolation, hallucinations and medication errors are at high levels.6

Moreover, when occurring together, central and peripheral vision loss can also increase the risk of geriatric falls and related injuries. Therefore, early diagnosis and prompt treatment of these conditions could prevent life-long morbidities and social isolation for the patient.

Although inconsistently, it has been suggested that intravitreal injection with anti-VEGF drugs for AMD can result in a thinning of the retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) in patients with POAG due to IOP fluctuations induced by these treatments, therefore contributing to disease progression.7 Therefore, even if the research results are inconclusive, the practitioner’s duty is to closely monitor the RNFL in patients with glaucoma receiving anti-VEGF treatments whenever possible.

In patients treated for neovascular diabetic retinopathy, it is important to be aware of possible IOP increase after intravitreal steroid8 or bevacizumab.9 These effects can last as long as six to 12 months. In addition, patients treated with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP, figure 4) have thinner RNFL than non-diabetic patients.10

Figure 4: Panretinal photocoagulation

II Glaucoma and systemic co-morbidities in the elderly

1 Hearing disorders and glaucoma

Hearing loss is a common problem among elderly individuals. Although some studies did suggest a direct association between glaucoma and sensorineural hearing loss, others do support them. Nevertheless, despite this uncertainty, there is a strong association between hearing and vision loss supported by scientific evidence and increasing continuously.

Therefore, the association between glaucoma and hearing loss is posing a huge challenge to the eye care providers. Possible problems with these patients can occur from difficulties with examination, communication and compliance to treatment. In addition, patients with both vision and hearing loss are exposed to risks such as reduced mobility and ability for self-care and high levels of anxiety and depression. Optometrists should step-up to this challenge and educate themselves on the best approaches for an early diagnosis but also appropriate management of patients with multiple sensory loss.

2 Glaucoma and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) in the elderly

It is estimated that OSA affects about 1.5 million adults in the UK; however, it is also predicted that around 85% of those are still undiagnosed. (British Lung Foundation, 2015). In elderly population, who suffer of an alteration of sleeping patterns, snoring, a manifestation of OSA is more common that in younger adults.

OSA represents an important risk factor for CVD, memory loss, anxiety and depression. In addition, OSA is associated with various ocular disorders, including glaucoma11. More details about OSA and glaucoma were already presented in this journal. The best management for these patients will include a close monitoring of their glaucoma as well as good communication with the rest of the patients’ care teams.

3 Glaucoma and diabetes in elderly people

Although there is no clear evidence that diabetes is a risk factor for POAG, it is often that patients can suffer from both disorders. It was also implicated that POAG in patients with diabetes and obesity, have a more severe form of the eye disease and should be monitored more closely, as high risk individuals. Another implication could be an increase in central corneal thickness (CCT) in severe diabetes. This can have an effect on IOP assessments as well as on POAG progression.12

4 Glaucoma and hypertension

Most of the existing evidences point to low and not high pressure being associated with POAG and NTG occurrence and progression. Nevertheless, as diseases of the old age, glaucoma and systemic hypertension co-exist in a large number of our patients.

This can have profound implications when considering blood pressure (BP) lowering drugs; when given or taken incorrectly, they will lower the BP beyond the body’s ability to cope with it and critical organs, including the eye, will not receive a proper blood supply. In glaucoma patients, this will contribute to glaucoma occurrence and progression. It is often the case in clinics when optometrists and ophthalmologists are faced with patients with IOPs at target but still progressing.

Until these patients are not properly screened for vascular risk factors or improper treatments for systemic hypertension, the cause will not be discovered and the situation will not be solved. These patients are often put unnecessarily on multiple antiglaucoma drops or undergo various surgical procedures in an attempt to lower the IOP even further and stop progression.

Nevertheless, until the above risk factors are addressed, the patient will continue to lose vision. These patients should be monitored more closely and the eye care practitioners should work together with the patients’ GPs and cardiovascular care team in order to improve glaucoma prognosis.

5 Glaucoma and stroke

It has been proposed that POAG and stroke are associated,13 with a diagnosis of POAG being a strong predictor for risk of stroke. This association can be blamed on the common ageing and vascular risk factors implicated in both disorders.

The eye care of the patient with stroke or at risk of one has been detailed in another issue of this journal.

6 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and glaucoma

CKD is a serious health problem, associated with multiple other co-morbidities, such as CVD, diabetes and obesity. It is estimated that one in 10 people have some degree of CKD, with half of individuals over 75 years old suffering from it (National Kidney Foundation statistics). These numbers are expected to increase, due to an ageing population and increased prevalence of associated chronic conditions.14

The risk factors for CKD are also contributors to certain ocular disorders, including AMD and glaucoma. For the particular topic of this article, it is important to point out that atherosclerosis, vascular endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation are common to both CKD and glaucoma.15

In addition to the possible association between the two disorders, people with CKD are at risk of developing IOP spikes during dialyses sessions. These spikes occur due to the fact that haemodialysis removes urea from circulation faster than from the cerebrospinal fluid or the aqueous humour, and the urea gradient created in this way causes the water to move into the anterior chamber, thus increasing the IOP.16

Optometrists should screen for glaucoma all patients suffering from CKD. In addition, patients with glaucoma and CKD will need to be monitored for IOP spikes during dialysis. These spikes can be extremely detrimental to the visual function, especially in advanced forms of glaucoma.

7 Glaucoma and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

The possibility that AD and glaucoma may share a common underlying mechanism has been increasingly realised over recent years. It has been suggested that POAG is an ocular form of AD and AD is a cerebral form of glaucoma. The two conditions have obvious associations: they are both chronic neurodegenerative diseases, are strongly related to ageing and their pathogenesis involves the loss of nerve cells by apoptosis.

Other aetiological theories linking AD and POAG have also been proposed relating, for example, to decreased cerebrospinal fluid pressure in both conditions17 raised intracranial pressure in association with raised IOP18 or the presence of common genetic risk factors.19 In addition, multiple studies have demonstrated an increased rate of occurrence and progression of POAG or NTG in patients diagnosed with AD and an increased prevalence of glaucoma in those with cognitive impairment or dementia.20,21

Particularities of caring for patients with ocular diseases and AD have already been published in this journal. Depending on the disease severity, optometrists and ophthalmologist should alter their management in patients with AD, paying particular attention to the type of tests they use, but also to medication, considering the effect on the patient’s quality of life (QoL) and compliance to treatment in each particular case.

8 Glaucoma and Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease represents a long-term neurodegenerative disorder that affects the motor system. Due to this fact, it can also affect the ocular motility. In addition, it is also associated with dry eyes, blepharospasm, diplopia, impaired contrast sensitivity and colour vision and affects visuo-spatial orientation.

It has been demonstrated that Parkinson’s disease occurs with higher frequency in patients with glaucoma.22 In terms of treatment, however, although levodopa and anticholinergics used for Parkinson’s disease could cause acute angle closure glaucoma attack in predisposed patients, they have no implication in POAG.

9 Glaucoma and depression in the elderly

It is estimated that patients with ocular diseases and vision loss have higher incidence of depression, anxiety and sleep disorders.

These changes are more pronounced in patients with multiple eye disorders or with dual sensory loss. When co-existing with glaucoma, depression affects the patient at all levels, including physically, functionally, socially and psychologically.23

In addition to the effect of the glaucoma diagnosis itself and loss of visual function, some antiglaucoma medication also increases risk for depression. Depression can also occur when glaucoma is complicated by other ocular side effects of the antiglaucoma drops, as detailed above.

Moreover, as glaucoma patients need to adhere to a strict schedule, they will have limited access to activities and social interactions than age-matched healthy individuals. This will result in non-compliance to glaucoma medication, which in turns affects prognosis and starts a vicious circle of more deterioration and depression.24

Co-existence of depression with old age eye disorders is now considered a public health issue. These patients need to be managed by a multidisciplinary team and eye care providers should work closely with psychologists, psychiatrists and other therapists in order to improve the prognosis and QoL of these patients.

Conclusion

It is often the case that when faced with a POAG patient, we concentrate only on this disorder and neglect other possible comorbidities. This practice, however, will have a detrimental effect not only on glaucoma management and prognosis, but also on the co-existing disorder as well as on the patient’s QoL.

It is important to remember that patients will deteriorate more when affected by multiple comorbidities than when they have only one condition. This situation is even worse in the elderly. Such cases should be monitored closely, using a multidisciplinary approach and each patient assessed and managed on an individual-tailored basis.

The General Optical Council (GOC) stepped up to the challenge imposed by an ageing population and ensured that UK optometrists have access to high quality training and professional certifications for a large number of clinical specialties, including some that are linked to ageing, such as glaucoma and low vision.

Nevertheless, these subjects cover only the tip of the iceberg. Geriatric optometry is a field that needs exploring in depth. Our optometrists should be properly prepared to adapt their eye exam and treatment to all the needs of elderly patients. ‘If optometrists are to provide care to the elderly as they must, it is imperative that every optometrist receive formal training in geriatric

optometry.’25

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the Optometry School, Aston University.

References

1 Banitt M, Jung H. Ocular surface disease in the glaucoma patient. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2018; 58: 23-33

2 Kastelan S, Tomic M, Soldo KM, Salopek-Rabatic J. How ocular surface disease impacts in the glaucoma treatment outcome. Biomed res Int 2013; doi: 10.1155/2013/696328

3 Fechtner RD, Godfrey DG, Budenz D, Stewart JA, Stewart WC, Jasek MC. Prevalence of ocular surface complaints in patients with glaucoma using topical intraocular pressure-lowering medications. Cornea. 2010;29(6):618–621

4 Bhartiya S, Sethi HS, Chaturvedi N. Cataract and coexistent glaucoma: a therapeutic dilemma. J Curr Glaucoma Practice 2008; 2: 33-47

5 Griffith JF, Goldberg JL. Prevalence of comorbid reytinal

disease in patients with glaucoma at an academic medical centre. Clin Ophthalmol 2015; 13; 1275-1284

6 Pelletier AL, Thomas J, Shaw FR. Vision loss in older persons. Am Fam Physician 2009; 79: 963-970

7 Shin HJ, Kim SN, Chung H, Kim TE, Kim HC. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy and retinal nerve fiber loss in eyes with age-related macular degeneration; a meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; 57: 1798-1806

8 Reichle ML. Complication of intravitreal steroid injections. Optometry 2005; 76: 450-460

9 Jaffar S, tayyab A, Matin ZI, Masrur A, Naqaish R. Effect of intra vitreal injection of bevacizumab on intre-ocular pressure. J Ayub Mad Coll Abbottabad 2016; 28: 360-363

10 Lim MC, Tanimoto SA, Furlani BA et al. Effect of diabetic retinopathy and panretinal photocoagulation on retinal nerve fiber layer and optic nerve appearance. Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127: 857-862

11 Santos M, Hofmann RJ. Ocular manifestations of obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13: 1345-1348

12 Kuman N, Pop-Busui R, Musch DC, et al. Cornea, 2018 doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001668. [Epub ahead of print]

13 Belzunce A, Casellas M. Vascular risk factors in primary open angle glaucoma. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2004; 27: 335–344

14 The global burden of chronic kidney disease and the way forward, Ethn Dis, 15 (2005), pp. 418-423

15 Wong CW, Wong TT, Cheng CY et al. Kidney and eye diseases: common risk factors, etiological mechanisms and pathways. Kidney International 2014; 85; 1290-1302

16 Intraocular pressure during haemodialysis: a review. Eye (Lond), 19 (2005), pp. 1249-1256

17 Wostyn P, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP. Alzheimer’s disease and glaucoma: is there a causal relationship? British Journal of Ophthalmology 2009;93:1557-1559.

18 Wostyn P, Audenaert K, De Deyn P. Alzheimer's disease-related changes in diseases characterized by elevation of intracranial or intraocular pressure. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2008;110:101-109

19 Huang W, Qiu C, von Strauss E, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. APOE Genotype, Family History of Dementia, and Alzheimer Disease Risk: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1930-1934.

20 Chandra V, Bharucha NE, Schoenberg BS. Conditions associated with Alzheimer’s disease at death: case-control study. Neurology 1986;36:209-211.;

21 Yochim B, Mueller A, Kane K, Kahook M. Prevalence of Cognitive Impairment, Depression, and Anxiety Symptoms Among Older Adults With Glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2011;[Epub ahead of print].

22 Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Glaucoma correlates with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in elderly: a national-based cohort study in Taiwan. Curr Med Res Opin 2017; 33: 1511-1516

23 Labiris G, Giarmoukakis A, Kozobolis VP: Quality of Life (QoL) in Glaucoma Patients. In Rumelt S (ed): Glaucoma– Basic and Clinical Concepts, 307-318. In Tech Europe, 2011.

24 Palcic G, Ljubicic R, Barac J, Biuk D, Rogoic V. Glaucoma, depression and quality of life: multiple comorbidities, multiple assessments and multidisciplinary plan treatment. Psychiatria Danubina 2017; 29: 351-359

25 Verma, S. B. Training Programs in Geriatric Optometry. Journal of the American Optometric Association, 1988, 59, 312- 315.