Patients who are eligible for a National Health Service (NHS) sight test, but unable to attend an optometrist’s practice unaccompanied, due to a physical or mental illness or disability, are entitled to request an NHS domiciliary sight test. When the area of domiciliary eye care was last discussed in 2014, it was noted that 481,674 NHS domiciliary sight tests were carried out in the UK in the 12 months between April 1, 2011 and March 31, 2012.1 More recent figures demonstrate an increase in the number of NHS domiciliary sight tests taking place in the UK, with 548,295 having been conducted in 2016/17.2-5 This rise in the demand for NHS domiciliary eye care, along with several regulatory changes which have taken place in recent years, would suggest that a review of the professional, legal and ethical responsibilities of optometrists working in this area would be a timely one.

The first part of this review will look at NHS provision, examination considerations and mental capacity.

NHS Provision

NHS domiciliary eye care falls under the umbrella of the General Ophthalmic Services (GOS) and as such, is commissioned at a local level throughout the UK. In Scotland, NHS Boards issue contracts and optometrists are paid via Practitioner Services. In Wales, the NHS Wales Business Services Centre supports the Local Health Boards, providing contractor services for primary care optometry, including contracts management and payment processing. In Northern Ireland, the Health and Social Care Board has responsibility for the provision of General Ophthalmic Services.

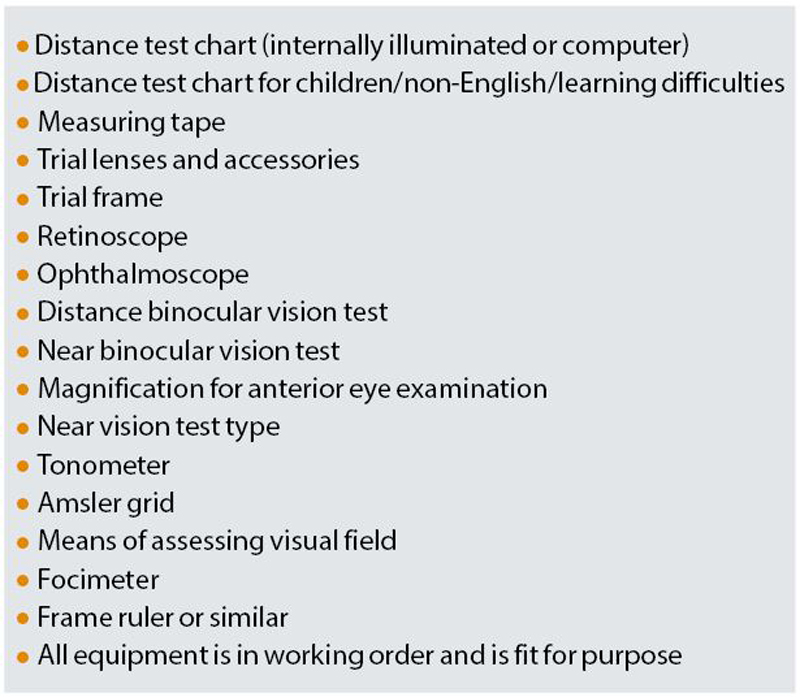

Table 1 Mobile equipment requirements

NHS England is in charge of commissioning Primary Health Care in England. Since its inception in April 2013, the organisation has been through a number of changes. Currently, for operational purposes, it is split into five regional areas. These are further divided into subregions to provide a more local service.6

Regulations stipulate that GOS sight tests may only be provided at a listed practice, at a patient’s normal place of residence (including residing at a residential home), or at some day centres.7-10 Although possession of a contract to provide Mandatory Services is sufficient if sight tests are to be carried out at a practice address, in England, a separate contract to provide Additional Services must be obtained in order to provide domiciliary sight tests. Any provider wishing to offer NHS domiciliary sight tests must apply for a contract with their relevant local commissioner. It is also important to note that a separate Additional Services contract must be held for each local area in which the contractor wishes to carry out domiciliary visits.7 However, the contractor is not obliged to cover the whole of the commissioner’s area.11 Applications for Additional Service contracts can be made by individuals or partnerships, or corporate bodies or limited companies.

A minimum standard of equipment is required for Additional Services contractors and Additional Services applicants are asked to bring their mobile equipment into the commissioner’s office so that it might be checked and approved. If this is likely to prove problematic, the commissioner can agree with the applicant a suitable time and place for inspection and approval. During this meeting, the applicant has the opportunity to answer pertinent questions about their facilities for record-keeping and their staffing arrangements.6,12 The minimum equipment for additional services contractors can be found in table 1.

In Scotland, if a practitioner, sole trader or body corporate is registered under part 1 of the ophthalmic list of the appropriate NHS Board then they may, where requested to do so by or on behalf of a patient, agree to provide ophthalmic services at the patient’s place of residence or day centre, providing the patient is eligible for a domiciliary visit.12

In Wales and Northern Ireland, providing a practitioner, sole trader or body corporate is registered under part 2 of the ophthalmic list, has stated to the appropriate local body that they wish to provide domiciliary services and agreed to follow the terms of service for mobile services, they may undertake domiciliary work.12

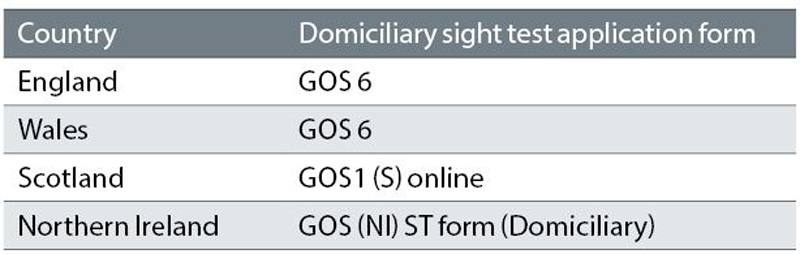

Table 2

Before visiting patients, contractors are required to inform the appropriate area team or health board of their intent to provide domiciliary services. In England and Wales, 48 hours’ notice must be given if one or two people will be visited at the same address, while if three people or more are to be visited, three weeks’ notice should be provided.7,9,13 In Scotland, the relevant health board should be notified one month in advance of any proposed visit to three or more people at the same address, while in Northern Ireland, 48 hours’ notice is required except if the situation is urgent, when no notification is needed.8,10,13

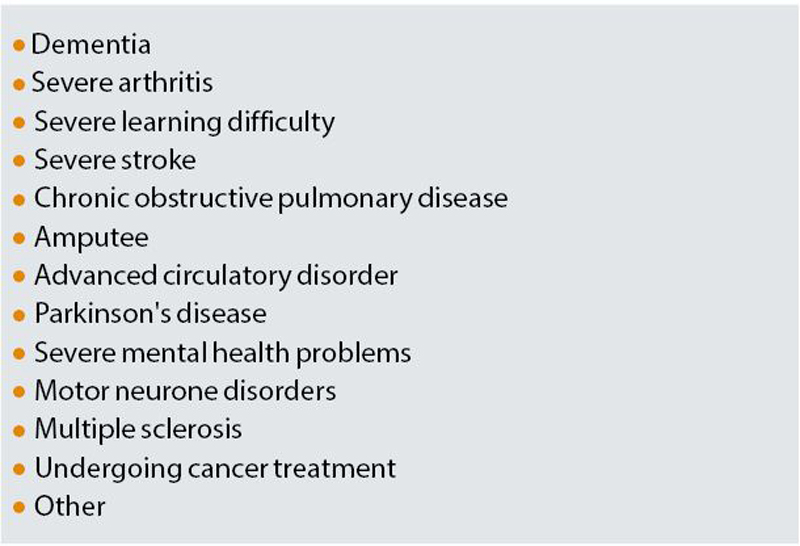

Table 3 Reasons why patient unable to attend optometric practice as offered by drop down menu on Scottish electronic GOS 1 form15

In England and Wales, any changes to the original notification given by the contractor may be made, providing that this takes place at least 48 hours before the intended visit. Up to three changes (additions or substitutions) may be made on the day of the visit, but only if it would not have been possible to give 48 hours’ notice, eg in respect of a new resident or a person who has only just developed an eye or vision problem.7,9 In Northern Ireland, 24 hours’ notice is required for any changes to a planned visit. However, if circumstances arise which mean that it would not have been possible to notify the Social Care Board in advance, it is possible to add up to three patients to those being tested.10 In Scotland, substitutions can be made on the day of the visit, providing the health board had received notification, at least a month in advance, of the substituted location or patients.8

If visiting a day care centre, the contractor should check in advance with the commissioner whether the particular centre complies with the definition of a day care centre.7-10 Although an appropriate domiciliary sight test application form should be completed (table 2), visits to day care centres do not attract a domiciliary visit fee.

When an NHS domiciliary sight test takes place, both the optometrist and the patient have a responsibility to ensure that the domiciliary visit is necessary. The optometrist should ask the patient to specify the specific illness or disability which prevents him/her from attending a practice and this should be noted on the relevant GOS form.7-10 Generic terms such as ‘housebound’, ‘immobile’, ‘wheelchair-bound’ or ‘resident of a home’ are insufficient. In Scotland, GOS claims can be made electronically (with paper based claims no longer being accepted after April 1, 2019),14 and the reason why a patient is applying for a home visit can be selected by the practitioner from a drop down menu (table 3).15 Giving the reason why the patient cannot leave home unaccompanied is the patient’s responsibility rather than the practitioner’s, and there is, therefore, no issue of medical confidentiality.7-10

Having a role as a carer for a person who is housebound, does not make that individual eligible for an NHS-funded domiciliary sight test, even if it is difficult for the carer to leave their house, due to their caring responsibilities. When completing the GOS form, the optometrist should also indicate whether the patient was the first, second, or third or subsequent person seen at that address on that visit.7-10

Current (April 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019) NHS domiciliary visiting fees paid to the contractor are set at £37.56 for first and second patients and £9.40 for third and subsequent patients.16 This amount can be claimed in addition to the sight test fee for each patient seen.

ExamInation considerations

Guidance issued by the Optical Confederation is clear that any patient receiving domiciliary eye care must receive the same quality of service as they would in a fixed practice consulting room.12 Additionally, individuals who have protected characteristics, defined by the Equality Act (2010), are protected from discrimination. Characteristics which may be relevant when considering providing domiciliary eye care are age and disability. In particular, service providers should not offer a lower standard of service to anyone with a protected characteristic.17

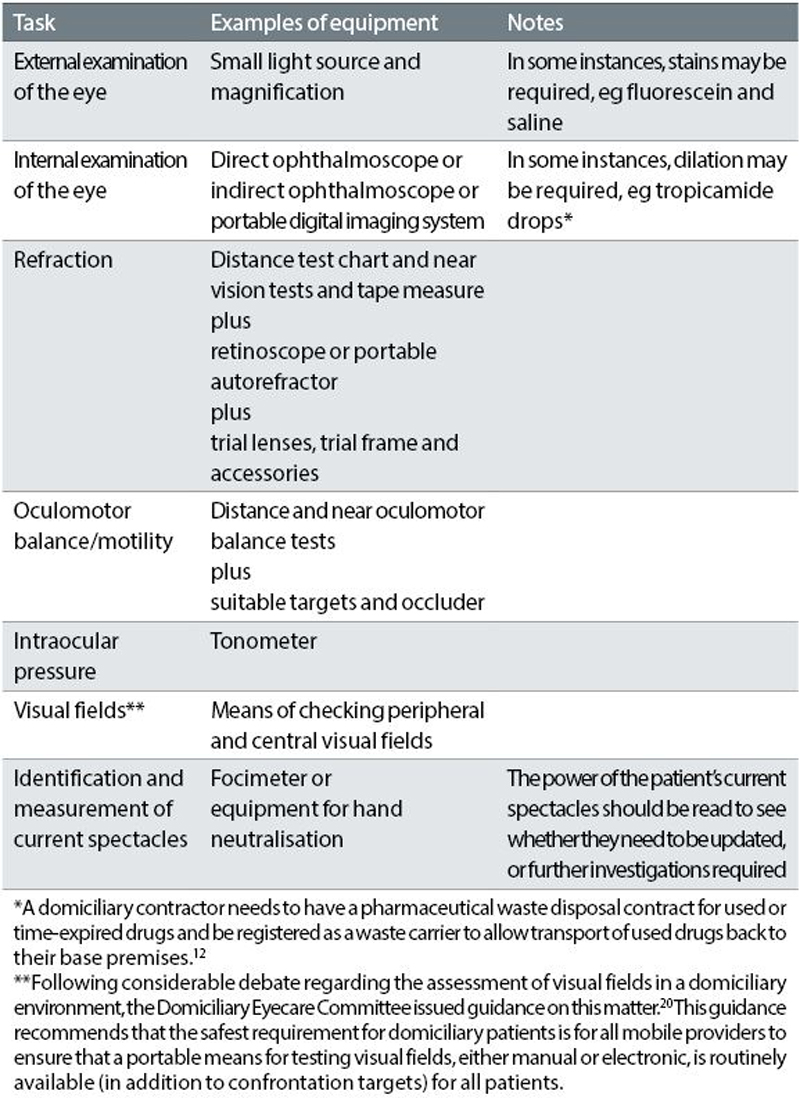

However, the College of Optometrists recommends flexibility when examining domiciliary patients, adapting techniques as necessary. In its Professional Guidance it advises that the optometrist should carry out whatever tests are possible to determine the patient’s needs for vision care for both sight and health, with the format and content of the eye examination being determined by the practitioner’s professional judgement and the legal requirements.18 Joint guidance from ABDO, FODO, the AOP and the College of Optometrists lists the tasks that a practitioner providing mobile ophthalmic services would normally be expected to perform and examples of equipment considered suitable to perform these tasks (table 4).19

Particular attention should be paid as to whereabouts in the residential environment the sight test will be carried out. The College of Optometrists acknowledges that in the case of a patient who does not leave their place of residence, carrying out an eye examination in this setting can be advantageous. This is due to the fact the practitioner is able to take into account lighting levels, television viewing distance, room set up, etc, before giving advice on achieving optimum vision.18 However, for personal protection, it is not advisable for the practitioner to enter any rooms other than the one that the patient is in at the time.12

Table 4

Information available to those who wish to arrange a domiciliary sight test advises that a room with good lighting and blinds or curtains to allow the room to be darkened should be available. The availability of easy access to a plug socket is also emphasised. Additionally, it is recommended that the optometrist should be able to get to both sides of the patient and that three metres of space should be available in front of the person’s bed or chair.13 Permission should be sought before moving furniture and the practitioner should ensure that any items moved are returned to their usual position at the end of the test.12 Rearrangement of a room’s layout can sometimes be distressing for an individual so if this is necessary, it can be beneficial for this change to be explained in advance of the sight test and for the person to be reassured that it is only temporary.13

It is also important to ensure that the patient’s dignity and privacy is respected within the domiciliary setting21 and the Care Quality Commission have emphasised this need in care homes.22 The sight test should take place in an area where patient confidentiality can be maintained and where interactions between patient and practitioner cannot be observed or overheard by other residents. Each patient should also be treated as an individual21 and group testing is, therefore, not condoned.

The Standards of Practice, issued by the GOC in 2016,23 make reference to these considerations in Standard 12.3: “Ensure that when working in the home of a patient or other community setting, the environment is safe and appropriate for the delivery of care.”

Patients should have a free choice as to which practitioner is consulted7,21 and it is important to remember that a practitioner must only provide a domiciliary eye examination at the request of, and with the consent of, the patient or a relative or primary carer.12 It is suggested that limiting patient numbers to five to seven per session (morning or afternoon) will ensure that patient care is not compromised.24 These points are of particular relevance in a residential home or day centre setting.

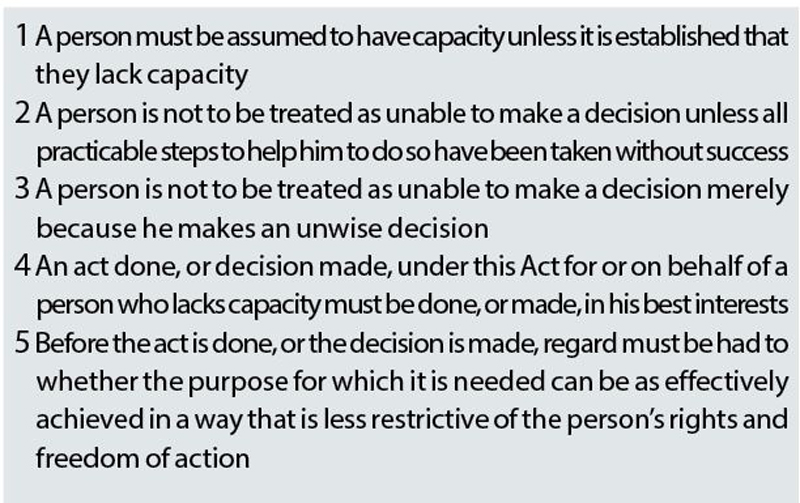

Consideration of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) may be appropriate when working with some domiciliary patients (table 5). This Act, which applies in England and Wales, provides a comprehensive framework for decision making on behalf of adults aged 16 and over who lack capacity to make decisions on their own behalf. Scotland has its own legislation, the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000, while in Northern Ireland the Mental Capacity Act (Northern Ireland) 2016 applies.

Table 5 The five key principles of the Mental Capacity Act (2005)25 are:

The Mental Capacity Act affects anyone with an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain.25

A fundamental principle of the Act is that people over the age of 16 are presumed to have legal capacity to make decisions for themselves, unless it can be shown that they lack the capacity to make the decision for themselves at the time the decision needs to be made. The Act also states all appropriate help and support should be given to enable people to make their own decisions or to maximise their participation in the decision making process. This could mean supplying relevant information in alternative formats, eg pictorially, or delaying decision making until a time when the individual is more able or more alert. It should be remembered that individuals who do not possess the mental capacity to make major decisions (eg giving consent to being referred to an ophthalmologist) may still be able to make more straightforward ones (eg colour choice of a new spectacle frame).

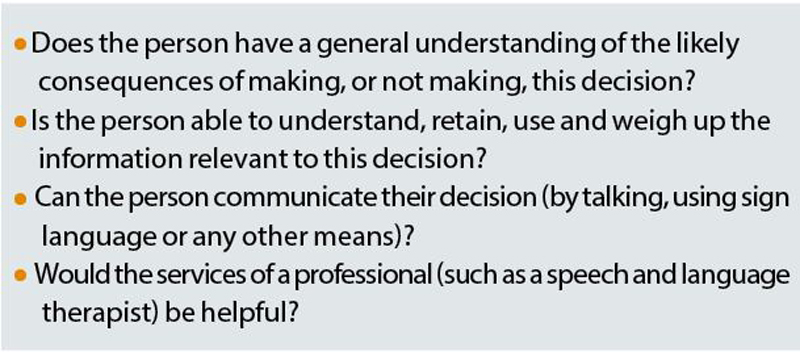

Table 6 Assessing a person’s ability to make a decision20

However, if a decision is made, or action is taken, on behalf of someone who lacks the capacity to make the decision or act for themselves, then the decision or action should be carried out in their best interests.26

If a doctor or healthcare professional proposes treatment or an examination, they must assess the person’s capacity to consent (table 6). Additionally, as a healthcare professional, an optometrist should work within the Code of Practice which accompanies the Mental Capacity Act.27 This Code explains that a person must not be assumed to lack capacity because of their age, their appearance, any mental health diagnosis they may have or any other disability or medical condition they may have.

Part 2 of this article will go on to review communication, consent, record keeping, prescribing considerations as well as look at looking at matters to take into account after the eye examination.

Catherine Viner is an optometrist and senior lecturer at Bradford University.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Kalpana Theophilus BSc MCOptom LLB (Hons) for her help in compiling this article.

References

- Optical Confederation (2013). Optics at a Glance 2012. Available online at: http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/key-statistics/optics-at-a-glance2012web.pdf Accessed 27th September 2018.

- NHS Digital (2017). General Ophthalmic Services activity statistics - England, year ending 31 March 2017. Available online at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/general-ophthalmic-services-activity-statistics/general-ophthalmic-services-activity-statistics-england-year-ending-31-march-2017 Accessed 24th September 2018.

- Health and Social Care Board (2017). Ophthalmic Quarterly Reports. Available online at: http://www.hscbusiness.hscni.net/services/2516.htm Accessed 24th September 2018.

- StatsWales (2017). NHS Ophthalmic Statistics by Year. https://statswales.gov.wales/Catalogue/Health-and-Social-Care/NHS-Primary-and-Community-Activity/Sight-Tests-and-Vouchers/nhsopthalmicstatistics-by-year Accessed 24th September 2018

- ISD Scotland (2017). General Ophthalmic Services Statistics http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Eye-Care/Publications/2017-10-10/2017-10-10-Ophthalmic-Report.pdf Accessed 24th September 2018.

- Slade S.V. (28th September 2018). Personal Communication.

- The Optical Confederation, AOP (2014, amended 2018). Making Accurate Claims in England. Available online at: https://www.aop.org.uk/advice-and-support/regulation/england/making-accurate-claims Accessed 28th September 2018.

- Optical Confederation (2017). Making Accurate Claims in Scotland. Available online at: http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/making-accurate-claims-in-scotland---2017-update.pdf Accessed 29th September 2018.

- ABDO, AOP, FODO, Optometry Wales (2007). Making Accurate Claims in Wales. Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/downloads/gos/Making_Accurate_Claims_in_Wales_2007.pdf Accessed 28th September 2018.

- ABDO, AOP, FODO, Optometry Northern Ireland (2007). Making Accurate Claims in Northern Ireland. Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/downloads/gos/Making_Accurate_Claims_in_Northern_Ireland_2007.pdf Accessed 30th September 2018.

- NHS England (2018). Eye Health Policy Book. Available online at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/eye-health-policy-book-v3-4.pdf Accessed 27th September 2018.

- Optical Confederation (2018). Providing Domiciliary Eyecare Services. Available online at: http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/providing-domiciliary-eyecare-services----march-2018-.pdf Accessed 29th September 2018.

- Thomas Pocklington Trust, The College of Optometrists, Optical Confederation (2013). Sight Tests at Home leaflet. Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/resource-categories/domiciliary-eyecare Accessed 1st October 2018.

- Directorate for Population Health, Primary Care Division (2017). Memorandum to NHS: PCA(O)(2017)2. Available online at: https://www.sehd.scot.nhs.uk/pca/PCA2017(O)02.pdf Accessed 30th September 2018.

- National Health Services Scotland Website: Using eOphthalmic Available at: https://nhsnss.org/services/practitioner/ophthalmic/eophthalmic/using-eophthalmic/general-ophthalmic-services-1-gos1/examination/ Accessed 30th September 2018

- FODO Website. Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/resource-categories/nhs-sight-test-fees Accessed 1st October 2018.

- Gov.uk website. Equality Act (2010) Guidance. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance Accessed 1st October 2018.

- The College of Optometrists (2018) Professional Guidance: The domiciliary eye examination. Available online at: https://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and-performance-domain/the-domiciliary-eye-examination/#open:99,100,101,102 Accessed 30th September 2018

- ABDO, AOP, College of Optometrists, FODO (2006) Equipment for Use in Mobile (Domiciliary) Ophthalmic Services (GOS). Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/downloads/domiciliary/domiciliary_equipment_guidance_July_06.pdf Accessed 30th September 2018.

- Domiciliary Eyecare Committee (2010). Field Screening in the Domiciliary Setting. Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/downloads/domiciliary/DEC%20Position%20Statement%20Visual%20Field%20Screening%20July%202011.pdf Accessed 1st October 2018.

- Domiciliary Eyecare Committee (2014). Code of Practice for Domiciliary Eyecare. Available online at: http://www.aop.org.uk/regulation/domiciliary/ Accessed 1st October 2018.

- Care Quality Commission (2012). Time to Listen in Care Homes. Available online at:http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/time_to_listen_-_care_homes_main_report_tag.pdf Accessed 1st October 2018.

- General Optical Council (2016). Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. Available online at: https://www.optical.org/filemanager/root/site_assets/standards/new_standards_documents/standards_of_practice_web.pdf Accessed 30th September 2018.

- Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network – Northern Ireland (2010). Best Practice Guidance for the Provision of Domiciliary Eyecare in Nursing/Residential Homes and Day Care Facilities. Available online at: http://www.fodo.com/downloads/clinical/eyecareaudit2010.pdf Accessed 1st October 2018.

- Mental Capacity Act 2005.Available online at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents Accessed 1st October 2018.

- The College of Optometrists (2018). Professional Guidance: Capacity to consent – adults Available online at: https://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/communication-partnership-and-teamwork-domain/consent/capacity-to-consent--adults/ Accessed 1st October 2018.

- Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice. Available online at: http://www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/protecting-the-vulnerable/mca/mca-code-practice-0509.pdf Accessed 1st October 2018..