In the first of these two papers, we discussed the requirements for undertaking a domiciliary eye care service. In this article, we will look at communication with the patient, record keeping, and the legal framework under which we should operate.

Communication

It is recognised that effective communication is important in any optometric consultation.1 A practitioner’s style of communication should be adapted to suit each individual patient and this may be particularly beneficial when examining a domiciliary patient, especially if the patient has dementia or another acquired cognitive impairment. Interacting with this type of patient may not seem straight forward or feel comfortable for many practitioners and the Code of Practice for Domiciliary Eyecare stipulates that providers of domiciliary eye care should ensure their personnel receive appropriate guidance in the specialist communication skills necessary for domiciliary patients.2 The Alzheimer’s Society suggests their ‘This is me’ form can be a useful support tool to enable health and social care professionals to build a better understanding of the individual and how best to communicate with them.3

- When approaching a person with dementia, it is recommended that one should move towards the individual from the front.4 The initial conversation should start with the optometrist identifying themselves5 and it is suggested that a more positive response may be obtained from some patients if they are addressed at first in a formal manner, using title and surname.4 Making eye contact and reducing extraneous noise can help the patient maintain focus on the optometrist and the task in hand.4,6 Additionally, if the practitioner positions themselves at eye level, this can help to maintain eye contact and avoids the practitioner appearing intimidating to a seated patient.4

When conversing with an individual with dementia, it is important to remember to keep sentences short and simple. It is also imperative not to rush the interaction.4,6 Breaking down more complex sentences into a series of more succinct and straightforward ones can make it easier for someone with dementia to understand what is being said. It is suggested that four to six words together are the optimum number for each sentence.5 Open questions should be avoided and sentences should be constructed to elicit a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.6,7

Eg. When taking a case history, the following may work well:5

- ‘I have some questions. I need some information. I need some information about your eyes. May I ask you a question? Do you have glasses? Do you wear your glasses all the time?’

It is also advised that real names are used for people and objects as this makes conversations easier to follow.7

- When showing a patient new frames, instead of asking, ‘Do you like them?’ try asking, ‘Do you like the glasses?’

Although linguistic understanding of conversations may diminish in patients with dementia, the message that is conveyed by the tone of the communicant’s voice and their body language will still be recognised.5 Therefore, the optometrist should endeavour to maintain a relaxed demeanour and encouraging tone of voice, while avoiding sudden, tense movements.

It should be remembered that individuals with dementia are unlikely to have requested an eye examination themselves. It is more likely that a relative or member of staff has arranged the visit on their behalf. The arrival of an optometrist can therefore come as a complete surprise. Even if their carer has mentioned the optometrist’s visit in advance, it is quite possible that the individual will not have retained this information. It is therefore good practice for the optometrist to explain the reason for their visit as part of their introduction to the patient.

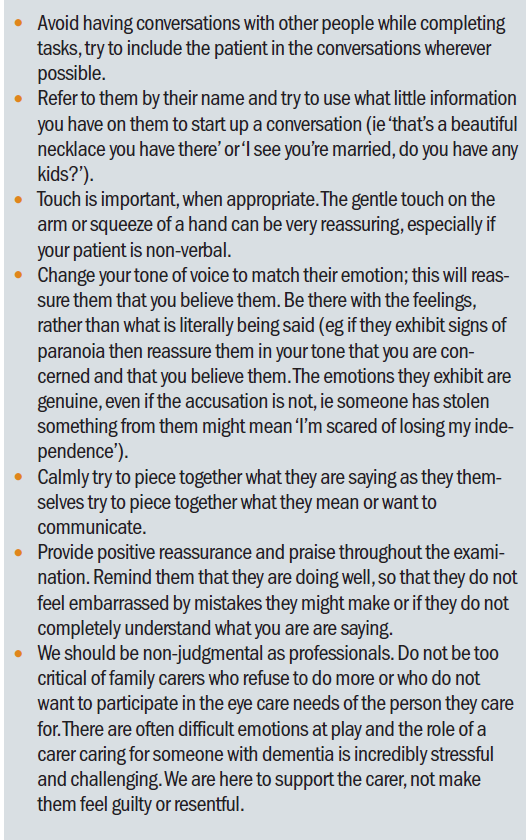

Table 1 suggests some ways of improving communication with a patient with dementia.8

Consent

It is vital to gain consent from the patient before commencing any of the test procedures and to take into account any verbal or non-verbal behaviour that could indicate that consent has not been given. This may be demonstrated by the patient turning their head away from the optometrist or by a more vociferous outburst. The GOC Standard of Practice 2.310 makes explicit reference to the need to consider all types of communication when interacting with a patient:

- ‘Be alert to unspoken signals which could indicate a patient’s lack of understanding, discomfort or lack of consent.’

Supplementary Guidance on Consent,11 also issued by the GOC, gives further advice on the need to consider the possible vulnerability of patients in domiciliary settings when it comes to considering whether or not consent has been given freely:

- ‘Voluntary consent means that the decision to consent or not to consent is made by the patient themselves based on informed consideration. Patients must not be coerced by healthcare professionals, relatives or others to accept a particular type of treatment or care, or in the sale and supply of optical appliances. You should be aware of situations in which patients may be vulnerable, for example, in domiciliary settings.’

If the patient appears to be unhappy at any point about the examination proceeding, it is paramount that the optometrist ‘downs tools’ and attempts to re-establish consent before continuing.

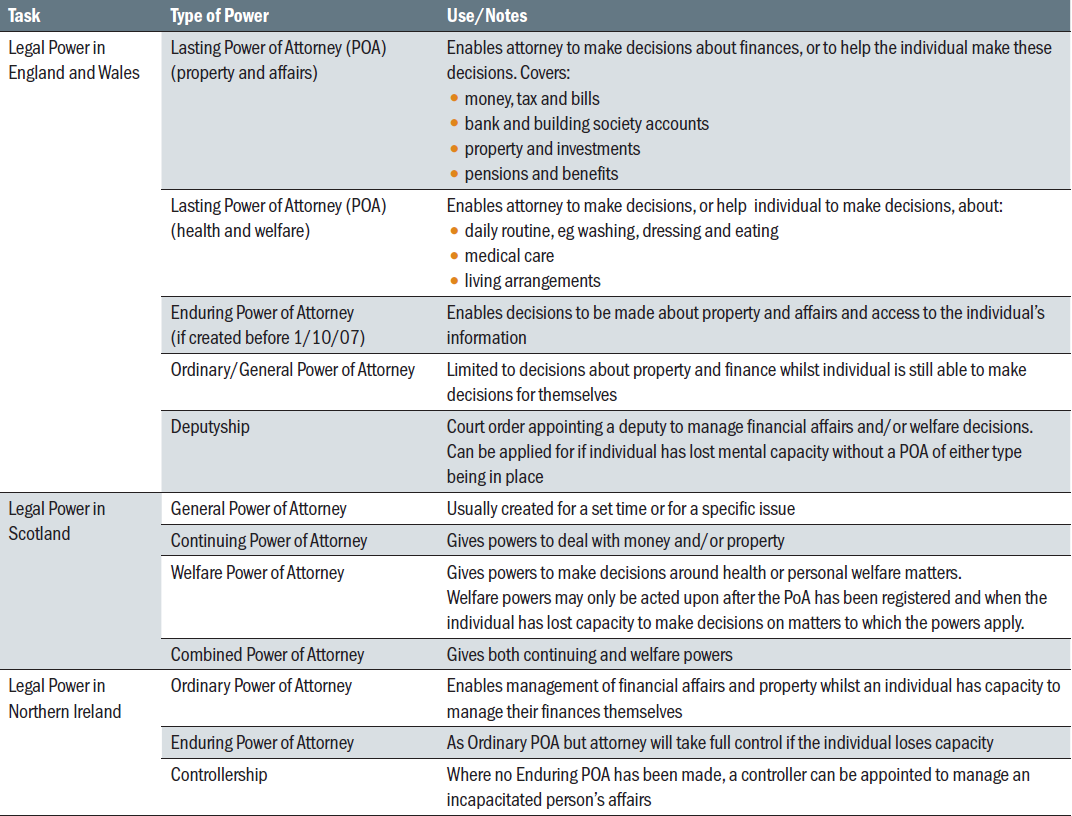

Assessing capacity to consent was discussed in part one of this article. Should the patient lack capacity to consent, it is important to consider who may give consent on behalf of the patient. Of particular note is the difference between the legal power to manage property and affairs and that which enables decisions to be made about an individual’s health and welfare (see table 2).

Table 2 Types of Legal Power in the United Kingdom12,14,15

Record Keeping

The College of Optometrists advise that an optometrist has a duty to ensure that they keep complete, contemporaneous and legible records of the patients under their care.16 Additionally, record keeping is a fundamental part of contract compliance within the GOS.17 When working in a domiciliary setting, extra information can be usefully included in a patient’s record. The reason for a domiciliary sight test and any eligibility for an NHS voucher should be recorded18,19 along with the name of any person who is accompanying the patient. It can also be beneficial to note the name of any individual with whom the patient has consented to share the results and recommendations of the sight test.20

As discussed in part one, it is recognised that, depending on the nature of the patient, the exact content and format of the examination may need to be varied.19 However, if it is impossible to include the full range of procedures due to patient’s medical limitations, the reasons should be noted on the record card.19,20

Prescribing Considerations

As with any patient, when deciding whether to prescribe an optical appliance, an optometrist should consider whether there is a relevant change in prescription and whether this improves the patient’s functional vision. The serviceability of the patient’s current optical appliance and whether or not it is actually used, should also be taken into account. Additionally, for patients with dementia or other acquired cognitive impairment, the individual’s ability to make the choice as to whether to have a new prescription made up should also be a factor in this process.20

After the examination

As well as issuing a spectacle prescription or statement that no correction or change is necessary, a practitioner should provide additional details summarising the outcome of the sight test with the patient or, with the patient’s consent, with their carer or care home. Additionally, the patient should be given the contact details of the provider.21

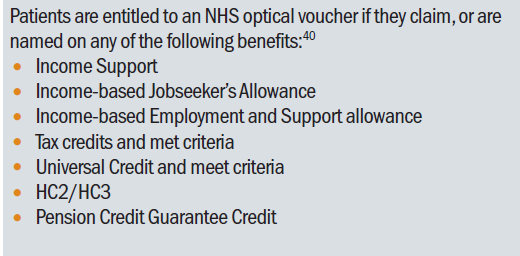

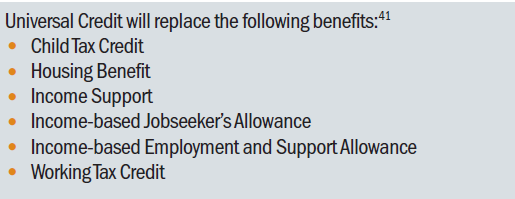

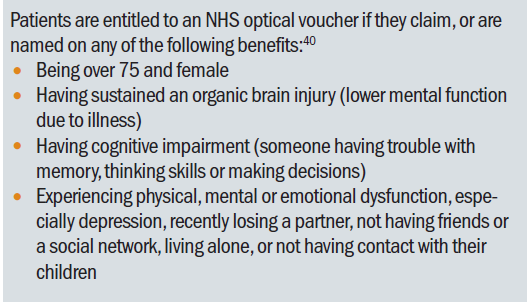

Table 3 Voucher entitlement  Careful consideration as to whether the patient is entitled to an NHS optical voucher on benefit grounds should be made (table 3).21 Universal Credit is currently being introduced in stages across the United Kingdom and will replace a certain number of these benefits (table 4).22 However, Pension Credit, of which a number of domiciliary patients may be in receipt, will not be affected. A clear distinction should be made between the two different types of Pension Credit; Guarantee Credit and Savings Credit. Only those receiving Guarantee Credit are entitled to an NHS optical voucher and an optometrist issuing such a voucher should satisfy themselves that the relevant benefit is being claimed. This may involve checking the applicable paperwork or calling the pension service to enquire. As an enquiry to this service will mean that the patient will need to answer a number of security questions over the phone, this approach may not be suitable in cases where the patient is hard of hearing or may be confused. A useful approach in this situation can be for the optometrist to explain matters to the pension service, asking to establish implicit consent. Once this is confirmed, the relevant information can then be supplied.23

Careful consideration as to whether the patient is entitled to an NHS optical voucher on benefit grounds should be made (table 3).21 Universal Credit is currently being introduced in stages across the United Kingdom and will replace a certain number of these benefits (table 4).22 However, Pension Credit, of which a number of domiciliary patients may be in receipt, will not be affected. A clear distinction should be made between the two different types of Pension Credit; Guarantee Credit and Savings Credit. Only those receiving Guarantee Credit are entitled to an NHS optical voucher and an optometrist issuing such a voucher should satisfy themselves that the relevant benefit is being claimed. This may involve checking the applicable paperwork or calling the pension service to enquire. As an enquiry to this service will mean that the patient will need to answer a number of security questions over the phone, this approach may not be suitable in cases where the patient is hard of hearing or may be confused. A useful approach in this situation can be for the optometrist to explain matters to the pension service, asking to establish implicit consent. Once this is confirmed, the relevant information can then be supplied.23

Alternatively, it may be possible to determine whether or not a resident of a care home is entitled to receive an NHS optical voucher by enquiring about how their care is funded. If local authority funding covers their fees completely, it is very likely that the resident is in receipt of Guarantee Credit. Although nursing and care staff will not be privy to this information, it may be possible to contact finance staff to clarify the situation.

Table 4 Benefits replaced by universal credit

Patients receiving domiciliary eye care are entitled to have their prescription made up by whomsoever they choose. Any provider agreeing to provide optical goods to a patient during a domiciliary visit should be mindful of the fact that an ‘off-premises’ contract will be created. This entitles the person placing an order to change their mind and withdraw from the contract without having to provide any specific reason why. The cooling-off period starts when the customer receives the product and lasts for fourteen days. Prescription spectacles and contact lenses, along with products valued below the value of £42 are exempt from this legislation.24 However, practitioners offering other items to domiciliary patients, eg non-prescription low vision aids, may find that the cooling off period applies to the transaction.

It is paramount that any spectacles dispensed are fitted individually to patients19 and it is important to remember that the supply of any optical appliances to patients who are registered sight impaired or severely sight impaired or who are under-16 is carried out by, or under the supervision of an appropriately registered person.25 It is recommended that any spectacles supplied are labelled with the patient’s name although this should be done sensitively with respect to the patient’s dignity and should take in to account infection control.19,20

It is important that providers of domiciliary services can offer continuing care to patients, being available for adjustments, advice, etc and do not see the sight test as a ‘one-off’ event.19,20 Patients should be informed in advance whether any payment will need to be made for any follow up service requested and in the event of any tolerance issues arising, fully trained staff must be available to attend to these.20

Safeguarding

All public services, including healthcare services, have a clear responsibility to ensure that people in the most vulnerable situations are safe from abuse or neglect. It is thought that the majority of domiciliary visits are made to adults who are considered at risk of harm.12 Certain factors have been shown to increase the chance of abuse (table 5).26

Table 5 Factors shown to increase the chance of abuse26

It is therefore important for domiciliary practitioners to remain alert to possible safeguarding issues. If a particular situation feels uncomfortable, or concerns about a patient’s safety are felt, practitioners should seek further advice from their professional body or their local safeguarding official.27

Conclusion

The Code of Practice for Domiciliary Eyecare reminds providers of domiciliary services that they are acting in a privileged position of trust.21 It can be predicted that numbers of those needing domiciliary visits will continue to rise. It is hoped that this article will assist those working in a domiciliary environment to give their best possible attention to the professional, legal and ethical obligations of this expanding and very valuable work.

Catherine Viner is an optometrist and senior lecturer at Bradford University.

References

- General Optical Council (2015). Optometry Handbook 2015. Available online at: https://www.optical.org/en/Education/core-competencies--core-curricula Accessed 29th October 2018.

- Optical Confederation (2013). Optics at a Glance 2012. Available online at: http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/key-statistics/optics-at-a-glance2012web.pdf Accessed 27th September 2018.

- Alzheimer’s Society (2017). This is me. Available online at: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/publications-factsheets/this-is-me Accessed 29th October 2018.

- Alzheimer’s Society (n.d.). Top Tips for Nurses: Communication. Available online at:https://southtees.nhs.uk/content/uploads/Top-Tips-for-Nurses.pdf Accessed 29th October 2018.

- Weirather, R.R. (2010). Communication Strategies to Assist Comprehension in Dementia. Hawai‘i Medical Journal 69: 72-74.

- Alzheimer’s Society Website (2018). Communicating and language. Available online at: http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=130 Accessed 1st November 2018.

- Stokes, G. (2013). Tackling communication challenges in dementia care. Nursing Times 109: 8, 14-15.

- Harvey, T. Communicating with the dementia patient. Optician, 08.06.2018.

- General Optical Council (2016). Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. Available online at:

- https://www.optical.org/filemanager/root/site_assets/standards/new_standards_documents/standards_of_practice_web.pdf Accessed 30th September 2018.

- General Optical Council (2017). Supplementary Guidance on Consent. Available online at: https://www.optical.org/filemanager/root/site_assets/standards/new_standards_documents/supplementary_guidance_on_consent.pdf Accessed 1st November 2018.

- Optical Confederation (2018). Providing Domiciliary Eyecare Services. Available online at:www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/providing-domiciliary-eyecare- services----march-2018-.pdf Accessed 29th September 2018.

- Alzheimer's Society. www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/legal-financial/types-lasting-powers-attorney

- Gov.UK website. Lasting power of attorney: acting as an attorney. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/lasting-power-attorney-duties/property-financial-affairs Accessed 2nd November 2018.

- Office of the Public Guardian (Scotland) website. Types of power of attorney (PoA). Available online at: http://www.publicguardian-scotland.gov.uk/power-of-attorney/power-of-attorney/types-of-power-of-attorney Accessed 2nd November 2018

- The College of Optometrists (2018). Professional Guidance: Patient records. Available online at: http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and-performance-domain/patient-records/#open:566 Accessed 1st November 2018.

- Quality in Optometry Website. Available online at: http://www.qualityinoptometry.co.uk Accessed 1st November 2018.

- The Optical Confederation, AOP (2014, amended 2018). Making Accurate Claims in England. Available online at: https://www.aop.org.uk/advice-and-support/regulation/england/making-accurate-claims Accessed 28th September 2018.

- Domiciliary Eyecare Committee (2014). Code of Practice for Domiciliary Eyecare. Available online at: http://www.aop.org.uk/regulation/domiciliary Accessed 1st October 2018.

- The College of Optometrists (2018). Professional Guidance: Principles of examining patients with cognitive impairment. Available online at: http://guidance.college-optometrists.org/guidance-contents/knowledge-skills-and-performance-domain/examining-patients-with-dementia Accessed 1st November 2018.

- NHS Website. Free NHS eye tests and optical vouchers. Available online at: https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/help-with-health-costs/free-nhs-eye-tests-and-optical-vouchers/ Accessed 2nd November 2018.

- Gov.UK website. Universal Credit. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/universal-credit. Accessed 2nd November 2018.

- Department for Work and Pensions (2015). Working with representatives – Guidance for DWP staff. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/461988/working-with-representatives-sept-2015.pdf Accessed 1st November 2018.

- Optical Confederation (2015). Cooling-Off Period Guidance. Available online at: http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/ocukcooling-ffperiodguidanceaug2015final.pdf Accessed 1st November 2018.

- The Opticians Act 1989, Amended 2005. Available online at: https://www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/opticians_act.cfm Accessed 1st November 2018.

- Office of the Public Guardian (2017). SD8: Office of the Public Guardian safeguarding policy (web version). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/safeguarding-policy-protecting-vulnerable-adults/sd8-opgs-safeguarding-policy Accessed 2nd November 2018

- Optical Confederation. (2017). Guidance on Safeguarding, Mental Capacity and the Prevent Strategy: Protecting Children and Vulnerable Adults. Available online at: http://www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/oc-safeguarding-guidance---updated--june-2017.pdf Accessed 2nd November 2018