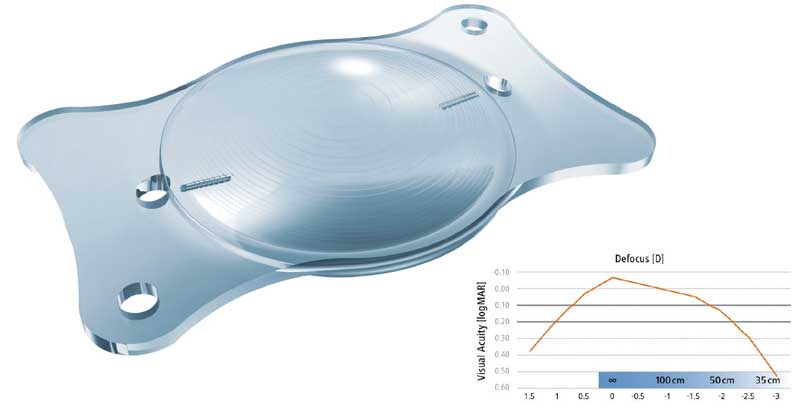

Over the past two decades or so, intraocular lenses (IOLs) have become increasingly sophisticated. In addition to traditional monofocal lenses, surgeons are now able to offer accommodating, extended depth of focus (EDOF), bifocal and trifocal IOL options to patients whose primary goal is to achieve as much spectacle independence as possible with a surgical solution (figure 1).

Figure 1: Many IOLs are not monofocal. Shown is the AT LISA multiocal toric IOL. Shown is an AT LARA toric IOL with a defocus curve

Within the increasing numbers of patients undergoing elective refractive lens exchange there is a cohort of patients with high expectations and exacting requirements regarding their visual outcome in terms of distance, intermediate and near vision.

Optometric clinical input in managing such patients is clearly important – either in a hospital setting, where the optometrist may work alongside ophthalmological colleagues, in a co-management partnership, or in community practice when the patient has been advised by their surgeon that they are ready to return to the care of their optometrist.

This article offers some guidance and pearls regarding the pre and postoperative examination of patients undergoing cataract surgery and refractive lens exchange.

Biometry and outcomes

Surgeons pay close attention to their refractive outcomes and the data are often reported as part of their revalidation process. One of the standard metrics audited following intraocular lens surgery is the postoperative spherical equivalent refraction versus the predicted postoperative refraction (PPOR). Using the postoperative subjective refraction data, surgeons can personalise the A constant values for their preferred intraocular lenses to make their biometric calculations of required IOL power as accurate as possible. The A constant values vary by lens design and type. This data can also be uploaded on to a website for users of partial coherence interferometry devices (figure 2), such as the IOL Master (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Germany), to update the optimised lens A constants (http://ocusoft.de/ulib/c1.htm). Increasingly, surgeons are being encouraged to report their outcomes data to external registries that can be accessed online by patients.

Figure 2: Zeiss IOL Master

Therefore, the role of the optometrist is becoming more and more important in the patient management pathway. In the past, cataract surgeons may have been content to see whether their patients had achieved uncorrected vision of 6/9 or better postoperatively, perhaps with an autorefraction reading, and made requests for subjective refraction only in cases of unexpectedly reduced unaided distance visual acuity (UDVA).

In refractive lens exchange cases, accurate subjective refraction, typically carried out by an experienced optometrist, and reliable assessment of unaided distance, intermediate and near vision monocularly and binocularly are important outcome measures. Corrected postoperative distance and distance corrected near visual acuity (CNVA and DCNVA respectively) are also used to evaluate the outcome of the surgery.

Similarly in cataract cases, the potential to attain 6/12 and 6/6 CDVA are key outcome measures and feedback to the surgeon from the optometrist in practice who performs the final refraction and assessment of visual acuity will be sought and highly appreciated.

Information for the optometrist

During the postoperative examination, it is helpful for the optometrist to have as much information as possible before the consultation, and this will typically include:

- Type of procedure – cataract or refractive or ‘clear’ lens extraction.

- Details of any operative or postoperative complications.

- Type of intraocular lens implanted – monofocal, EDOF or multifocal.

- Time since surgical procedure.

- Predicted postoperative refraction – plano, monovision, or to meet other requirements such as to match a still phakic eye in a unilateral cataract extraction case.

Where the optometrist has fostered a good working relationship with the surgeon and/or has a loyal patient base, then the referring optometrist will receive a letter from the treating surgeon including the details above prior to seeing the patient postoperatively. The patient will also have been issued with a credit card sized IOL information record, which also indicates the type of intraocular lens implanted. Further details can also be gleaned during a brief discussion with the patient regarding their procedure as a natural part of the history and symptoms.

Pre-screening

It can, in some cases, be helpful to have an initial autorefractor reading prior to seeing the patient. Where this procedure is carried out by another colleague in the practice, if the patient is unhappy with their outcome for any reason, they will often have communicated this to that colleague, and sharing this information enables the optometrist to be forewarned.

Similarly, it may be evident, in most cases from autorefraction (and keratometry if this is also provided by the device), whether we have a refractive surprise. For example, on the rare occasion a toric intraocular lens has rotated out of alignment in the early post-operative period, there may be a large degree of residual astigmatism present, which can help explain any reduction in unaided vision.

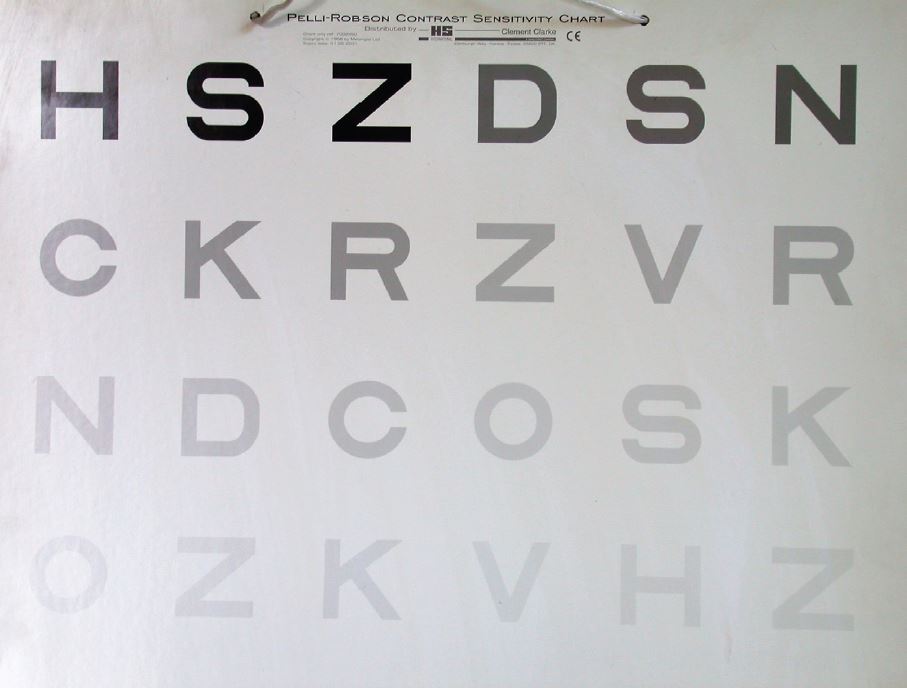

Refraction

It should be noted that, where multifocal IOLs have been implanted, autorefractor results may be inaccurate (figure 3). With some IOL designs, the autorefractor may indicate -1.00 to -1.50DS more myopia than is actually present. The experienced optometrist will quickly recognise this, as the level of uncorrected acuity will not relate to the autorefractor result refraction. For example, a patient who can achieve 6/7.5 unaided will not have a refraction of -1.50DS. Where rotationally asymmetric IOL designs have been implanted, the autorefractor reading of the cylinder component can also be inaccurate.

Figure 3: Autorefraction can be useful, but results may be inaccurate with multifocal IOLs.

Patient examination

Figure 4: Contrast sensitivity and other assessments of visual function would be useful but may be time-consuming

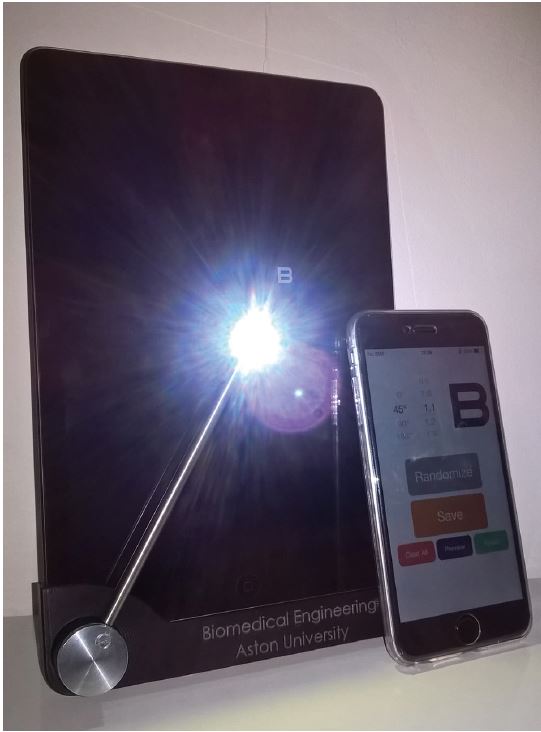

In patients with monocular IOLs, the examination process should be reasonably straightforward. With multifocal IOLs, while an evaluation of visual performance at different distances would ideally be complemented by assessment of contrast sensitivity (figure 4), objective assessment of dysphotopsia (for example using an Aston Halometer, figure 5), reading speed and defocus curves, these measures can be time consuming and difficult to perform as part of routine follow up.1

Figure 5: The Aston Halometer (courtesy of Professor James Wolffsohn)

However, it is always useful before any clinical measurements are taken, to gauge the level of patient satisfaction. Patients undergoing refractive lens exchange are counselled carefully on the risks and benefits and the management of expectations is naturally key in this type of elective surgery. Therefore, the optometrist may find that sometimes patient satisfaction does not necessarily correlate with the clinical findings. One patient may be delighted with vision of 6/9 unaided in the presence of a small amount of residual cylinder, eg -0.75 D, whereas another patient with the same outcome, may be seeking further refractive enhancement. It is therefore important, if the patient is perfectly happy with their binocular outcome, not to inadvertently suggest that their outcome is in some way sub-optimal simply because 6/6 distance acuity has not been achieved in one or both eyes. If the patient interprets something is not as it should be, they may become unduly worried and end up back with the treating surgeon who will ultimately have to provide the necessary reassurance as appropriate.

Notwithstanding, where a patient is unhappy with their outcome, the optometrist should consider referring the patient back to the treating centre for review and in a small number of cases, enhancement with laser vision correction or secondary lens will be a possible option. Clearly an accurate refraction is required particularly where this will form part of the planning process for any future intervention being considered.

After advanced technology IOL surgery, patients may need to be encouraged to try to read as far as possible down the chart, and not to give up too soon. This is especially important with multifocal IOLs because the patient has simultaneous distance and near images. Therefore, there needs to be a degree of neuroadaptation over the first few months or so as the brain ‘gets used to’ which image to concentrate on in different viewing situations. In the early postoperative period, these patients often need to spend a few moments looking at the chart and they often comment their distance acuity gets better as they do so. Encouragement to ‘try the next line’ until they are making three or more errors is often helpful and reassuring for the patient. The optometrist needs to allow sufficient time to obtain an accurate assessment of their monocular and binocular vision which is important for the detection of change as well as for accurate assessment of the true clinical outcome. If the patient can achieve 6/6 or better at distance this needs to be captured. This, coupled with assessment of monocular and binocular near and intermediate vision at the appropriate distance, and the patient reported outcome (including satisfaction) provides a fuller picture of the outcome.

Presbyopia correcting intraocular lenses

As with contact lenses, monovision can be achieved with intra-ocular lenses and can give a high rate of spectacle independence with minimal dysphotopsia side effects in appropriately selected patients.2 Surgeons can achieve this in a number of ways using two monofocal IOLs or adopting a modified monovision approach whereby a combination of monofocal and multifocal or EDOF lens designs are used.

Restoring accommodative function that is similar to that of the young eye, remains the ‘holy grail’ of presbyopia correction.3 The ciliary muscle of the ageing eye retains some ability to contract, giving hope that implanting a flexible IOL after removing the crystalline lens could restore some level of ‘pseudo’ accommodation. However, the optimal accommodating IOL with a wide range of accommodative amplitude still remains elusive although progress has been made and a number of IOL designs are in varying stages of development and commercial use. Different strategies are being used in these lenses in order to achieve the required dynamic changes in focus.4

At present, accommodating IOLs arguably have a role for patients who wish to gain good distance vision with some level of ‘social reading’ with less risk of dysphotopsia symptoms such as glare and haloes. These patients will be counselled that they may have difficulty reading smaller print or reading in low light levels. With some earlier designs, surgeons would generally encourage patients to read as much as possible unaided, especially in the first three months postoperatively as they needed an active ciliary muscle to optimise the performance of the lens. An exception to this was with Crystalens AO (Bausch + Lomb, Rochester, USA) where, in the first seven days, the patient may have been prescribed atropine 1% to relax their accommodation and asked to refrain from ‘trying’ to read and use +3.00D reading glasses. This was because the lens needs to be vaulted towards the posterior lens capsule for the best outcome and to reduce any forwards vaulting while the lens was settling.

Once this period was over, patients often appreciated the support of the optometrist as they adapted to using the lenses, with advice about lighting and demonstration of how their reading ability was improving. Studies have shown that geometrical and alignment changes in the IOL such as induction of higher order aberrations, lens tilt and miosis, rather than actual forward movement, contribute to the increased depth of focus observed in some patients with some designs.4 It should be borne in mind that patients with a degree of ‘pseudoaccommodation’ have the potential to be over-minused during the refraction process.

Patients with presbyopia correction IOLs can be offered extended depth of focus, bifocal or trifocal intraocular lens implants and the remainder of this discussion concentrates on those lens types. There are various options available within each of these categories nowadays (including toric options). Surgeons can adopt a mix and match approach, implanting the second eye with a different near addition power bifocal (such as +1.50 versus +3.00), or even a different lens design to the first eye in order to optimise the range of binocular clear vision and the level of spectacle independence achieved.

Extended depth of focus IOLs (such as the Symfony IOL, Johnson & Johnson, Vision, Santa Ana, CA, USA, or the AT LARA, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) are designed to give a good balance between spectacle independence and less visual side effects. They are designed to offer high levels of spectacle independence from far to intermediate distances, and may be an attractive option for patients with active lifestyles, who do not mind wearing reading glasses for some near tasks and who may be more sensitive to visual side effects at night.

For patients seeking maximum possible spectacle independence at all distances with the possibility of some night vision disturbances, options such as a trifocal IOL (such as the Panoptix, Alcon, LISA Tri (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) may be considered. These offer broadly similar distance visual acuity levels compared to EDOF lenses, with better vision at near, and better vision at intermediate distances compared to bifocal lenses.

The surgeon will aim to select the IOL combination that will best satisfy the requirements of each individual patient. Generally, the nondominant eye is implanted first with a lens that may be optimised for near distances. With some IOL designs, an eye with good visual potential may be expected to see N4 or N5 at a distance of approximately 40cm or so (depending on the near addition power of the IOL). Trifocal IOLs offer good distance vision, and depending on lens type, may have a +1.66DS intermediate addition and a +3.33DS near addition in the IOL plane, offering good levels of near and intermediate vision.

It is useful therefore during the examination to consider what lens type has been implanted, and what was the expected outcome. Was the patient meant to have monovision or another option, were they to be left with as much spectacle independence as possible, and were there any other factors to consider (such as low-grade amblyopia in one eye)? The answers will help the examination and discussions to be framed accordingly.

Because the patient is presbyopic and may have been used to holding things further away, the new ‘optimal’ reading distance may be unfamiliar to them in the early postoperative phase. Depending on lens type, the optometrist may find that when they hand the patient the reading chart, they will automatically read N8 or N10 at a longer working distance (figure 6). At this point, they can be gently encouraged to bring the chart closer and see whether that improves things. They can be reminded they are the ‘opposite’ of how they were – if they pick something up and cannot read it, they can try bringing it closer and it may well then come into focus. Similarly, with intermediate vision, such as using display screen equipment, the working distance may have to be slightly altered if patients report reduced clarity for such tasks.

Figure 6: Working distance may need to be different from the habitual one for a patient

It is important to note when refracting patients who have had trifocal IOLs, as there is already an in-built intermediate and near addition, a supplementary spectacle addition for intermediate and near is not required. Therefore, near vision can be assessed unaided and with any distance correction required. Unaided near vision can then be compared with ‘distance corrected’ near vision to give a true reflection of the near performance of that lens.

After first eye surgery, patients may report that they have difficulty with the computer display screen with higher addition bifocal lenses, as their working distance is too far away for the near part of the lens and too close to have clear vision through the distance part. If this is noted, the surgeon may advise a lower addition bifocal lens in the dominant second eye to provide better intermediate vision. The optometrist should bear in mind that near vision with the lower addition lens may be around N8 or so and not be surprised at the difference between eyes. It is important to remember that the goal of the surgeon will be optimal vision across as wide a range as possible binocularly, if this is what the patient desires.

With so-called advanced technology IOLs, the subjective refractive outcome should typically be close to the predicted post-operative refraction (often, but not always, near emmetropia) and the expected subjective refraction should relate to the unaided distance and near visual acuity. It may be more difficult to get a crisp end point during the subjective refraction, due to the IOL design and/or possible dry eye issues causing fluctuations in vision, typically the latter are most prevalent in the early post-operative period.

Referral back to the treating provider

Finally, if the patient expresses concern or dissatisfaction with their outcome, or appears to have developed a complication (visual acuity worse than expected, vision dropping, patchy or other unexplained signs or symptoms), the optometrist should always liaise with the treating surgeon who will be more than happy to re-examine the patient. Bear in mind that cystoid macular oedema and posterior capsule opacification will impact on

distance and reading ability. With PCO it may be necessary at some stage – even years after treatment – to refer the patient back for attention and possible YAG laser capsulotomy.

Summary

Optometrists and their patients will benefit from the experience gained in post-operative examination of patients with a variety of intraocular lenses. The field is fast changing and advances include IOLs that can have multifocality applied to them (or removed) after the primary surgical procedure as well as bifocal and trifocal designs that can be implanted as secondary lenses in pseudophakic patients who subsequently become interested in becoming more spectacle independent. Keeping up to date helps build practices, patient loyalty and respect and good optometrist-surgeon relationships that will ultimately benefit patients. There is a wealth of information aimed at both patients and practitioners available in the literature and on the websites of IOL manufacturers and it is worth finding out which may be the preferred lenses of local consultants.

Christa Gore is an optometrist at the Optegra Manchester Eye Hospital and Dr Clare O’Donnell is Head of Eye Sciences at Optegra and a Reader at Aston University.

References

- Kretz F. (2015). Top tips for premium IOL refraction. The Ophthalmologist. https://theophthalmologist.com/subspecialties/top-tips-for-premium-iol-refraction. 12/2/2015. Accessed 31 1 2019

- Labiris G, Toli A, Perente A, Ntonti P, Kozobolis VP (2017). A systematic review of pseudophakic monovision for presbyopia correction. Int J Ophthalmology 10 992-1000

- Wolffsohn JS and Davies L (2019). Presbyopia: effectiveness of correction strategies. Prog Ret and Eye Research. DOI 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.09.004

- Pepose JS, Burke J, Zazi MA (2017). Accommodating Intraocular Lenses. Asia Pac J Ophthalmology (Phila) 6 350-357.