Glaucoma in its various forms is one of the most common ocular conditions, both primary and secondary care settings. It is thought that around one million outpatient visits are made each year in the UK for glaucoma-related appointments. This makes glaucoma the sixth most common reason for outpatient attendance according to underlying condition of any health problem in the UK. In the past 25 years, glaucoma care has progressed significantly in terms of our understanding of intraocular pressure (IOP) reduction, and the medications available to achieve the best treatment for the patient has greatly expanded.

To define what ‘best treatment’ means for any patient, I will quote Professor Augusto Blanco, a renowned ophthalmologist in the field: ‘The general aim (of treatment) is to maintain the patient’s sight, while as much as possible maintaining their quality of life.’

As clinicians, it is also in our interests to achieve a treatment balance that controls the disease but causes the least side effects as possible, and so minimise the number of clinic visits required for each patient. When prescribing glaucoma medications, it is impossible to accurately predict which patients will experience problems. However, it is useful if we can identify any situations where there might be an increased risk given our knowledge of the medications.

This article will explore the various different classes of pressure lowering eye drops currently used and discuss the most common side effects of each. It will also highlight the various situations where certain drugs should be avoided, or at least approached with caution.

The Need for Treatment

Before discussing drug treatments, it is worth mentioning that we first need to identify a need for or benefit from treatment. The key underlying concept requires us to ask the following question: ‘Is this patient likely to suffer visual loss within their lifetime as a result of their glaucoma and will this have a negative impact on their quality of life?’ A crystal ball might be needed to answer this, but we can take into account the clinical findings, patient age, general health and visual demands in order to give a sense of how aggressive a treatment regime is justifiable.

The general principle must be to treat the patient with the minimum amount of medication that is required to either control their existing disease state or to limit the future risk of disease impact. Usually, this means:

- Initiating treatment with a medication

- Reviewing the IOP to see if it has reduced to a safer level where you think the risk of damage will be reduced

- Monitoring for any disease progression

Multiple or combination drops are considered when progression is demonstrated or when one drop does not reduce the IOP to a level that is thought to be safe.

In modern glaucoma practice, there are four main groups of drugs used topically to lower IOP, namely:

- Prostaglandin analogues

- Beta-blockers

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

- Alpha-agonists

At the last count, there were approximately 30 different preparations available in the UK, if you include the various combinations products and preservative-free versions of these products. Add to that the numerous different manufactured preparations with slightly different formulations for many of the medications, and there are suddenly a considerable number of variations to be aware of. The management of most patients should be straightforward, and they can be controlled well with just one or possibly two medications with few effects, However, in some cases there can be a fine balance between adverse side effects and effective treatment in the face of a progressive disease.

We will now take a closer look at each of the drug groups.

Prostaglandin Analogues

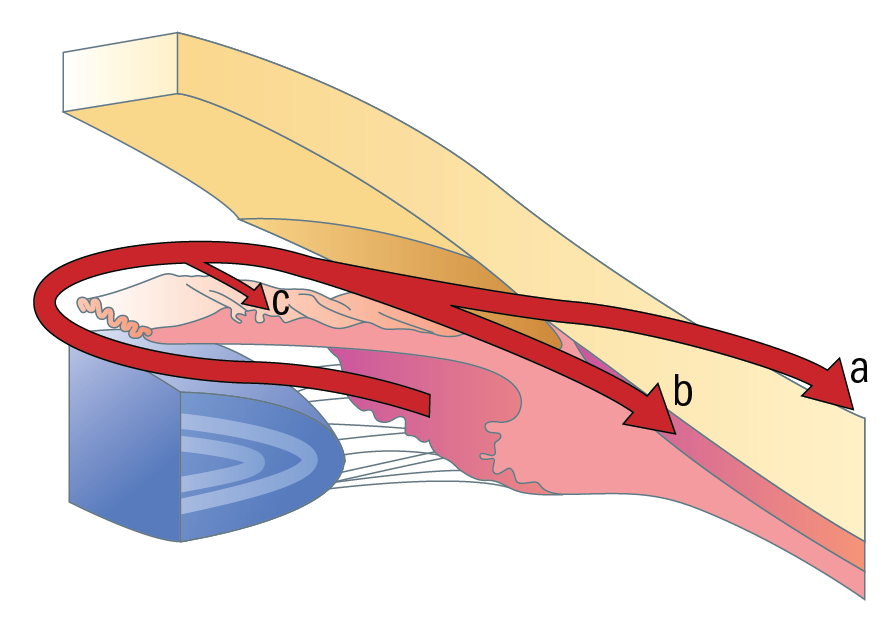

This group of drugs came into use in the late 1990s and has proved integral to the management of glaucoma. Prostaglandin analogues (PGAs) reduce IOP by increasing the outflow of aqueous through the uveoscleral outflow route. In humans, uveoscleral drainage represents around 10% of total outflow (figure 1). The exact mechanism for this is not well understood. However, PGAs are effective in bringing IOP down by an average of 20 to 30% from baseline. PGAs can be prescribed in both preserved and preservative-free versions, as well as in combination with the beta-blocker timolol (see later).

Figure 1: Aqueous drainage routes; (a) trabecular (b) uveoscleral (c) iris

The main topical PGAs in use are:

- Latanoprost

- Tafluprost

- Travoprost

- Bimatoprost

One of the early concerns when they first appeared was around the fact that prostaglandins are mediators in a whole variety of functions in healthy tissues throughout the body, including inflammation. Clinicians were worried that PGAs might encourage inflammation or exacerbate ocular inflammation where it was already present. There were also predictions that they might cause cystoid macular oedema. In reality, these concerns have never really played out. As a precaution, it is usually advisable to avoid PGAs in aphakic eyes or in those with a compromised lens capsule.

PGAs did, however, cause some unusual cosmetic side effects. The first of these was a change to iris colour, most noticeable when one eye only was being treated. This irreversible change is thought to be brought about to an increase in melanin in the iris structure resulting in a darkening of eye colour. The extent of discolouration is to some extent influenced by the original colour of the iris. Hazel coloured eyes consisting of a mosaic of different colours have been found to be affected to a greater extent than eyes of a more uniform colour, such as dark brown or blue. Discolouration occurs in between 10 to 18% of patients within the first two years of treatment, with those of patients over the age of 75 being at higher risk. It is worth warning patients of this possible side effect, and perhaps considering treating both eyes to maintain symmetry. It is also worth noting that there is a significant online trade for such drugs, especially in the US, where people are using them deliberately to change their eye colour.

A second adverse effect, also linked to increased melanin levels, is a change in peri-ocular appearance whereby the skin becomes darker. In contrast to the iris changes, this is reversible and will slowly resolve if usage of the drops ceases.

The third cosmetic change of interest associated with topical PGAs is increased eyelash growth. Up to 50% of patients experience one or more of the following changes:

- Increased length

- Increased thickness

- Increased number

- Darker colour

- Increased curliness

Again, this is something that might be worth pre-warning the patient of.

As prostaglandins are involved in uterine contractions in late pregnancy, PGAs are usually avoided in pregnant patients. However, it is thought that the actual plasma concentration as a result of topical PGA use would be very low and unlikely to have any significant impact on the foetus.

Along with most other topical preparations, other known ocular side effects can occur and include:

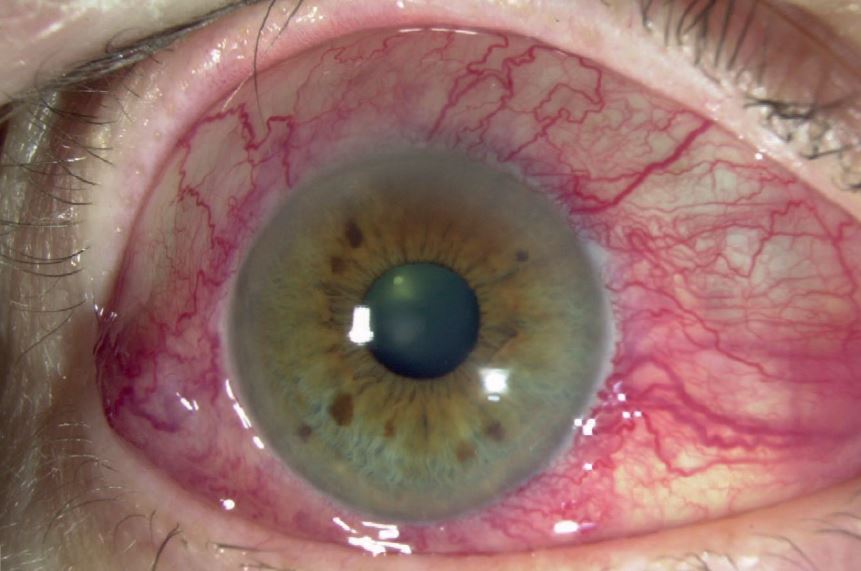

- Conjunctival redness or hyperaemia

- Sensations of burning, itching and irritation

However, these effects are most likely to be related to the other constituents within the PGA preparation, such as a preservative (figure 2).

Figure 2: Conjunctival hyperaemia may be due to preservatives used in some drug formulations

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers predate the introduction of PGAs and were the first line treatment in most cases prior to this. Nowadays, they tend to be used as second or third line treatment, often in combination with other drug groups. The two main drugs used currently are:

- Timolol

- Betaxolol

Timolol is available as a once daily or twice daily dose, and both drugs are available in either preserved or non-preserved forms.

Beta-blockers reduce IOP by reducing the rate of aqueous production. Again, their exact action is not fully understood, but they seem to have some effect on the ciliary epithelium. Aqueous is first secreted from the ciliary processes. Typically, a beta-blocker may reduce the IOP by between 15 to 20% from baseline.

There is, however, one area of concern regarding the use of topical beta-blockers that needs to be considered.

When used topically, any beta-blocker can be detected in the blood serum in a sufficient concentration to have an effect elsewhere in the body. This is partly due to the fact that ocular instillation avoids first-pass liver metabolism. Beta-blockers can have an effect on β1 receptors, β2 receptors and the central nervous system (CNS) receptors causing a variety of problems.

- β1 receptors – blockade of the β1 receptors may reduce cardiac output by slowing down the heart rate (bradycardia), reducing myocardial contraction and lowering systemic blood pressure. This could be potentially serious for any patient who has cardiovascular disease, and so should be avoided. For these reasons too, it is also best practice to avoid a topical beta-blocker drug for any patients who are already using an oral beta-blocker for blood pressure control. Interestingly, in patients with normal tension glaucoma (NTG), the advice is to avoid topical beta-blockers in the evening as they increase the risk of overnight systemic hypotension. This is significant, as NTG is a disease of reduced optic nerve head perfusion, so taking a beta-blocker at night might inadvertently reduce blood flow to the nerve, so risking further nerve damage.

- β2 receptors – blockade of the β2 receptors may affect the pulmonary system causing increased airway constriction and bronchospasm. Again, this could be serious for patients with pre-existing conditions such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Central nervous system – impacts of topical beta-blockers upon the CNS are less well understood than those upon beta receptors. However, known possible adverse effects include drowsiness, fatigue, impotence, depression, reduced libido and sleep disturbance.

Given the above list of problems, beta-blockers sometimes get a bad press. However, they remain an incredibly important part of glaucoma management strategy and remain in common use. The key for the clinician is to be aware of the risks, and to identify patients who might be at risk of cardiac and pulmonary side effects through a clear history.

With relation to the CNS issues, it is good practice to pre-warn the patient of potential effects so that, if they do start to experience any of these, they can report back at the earliest opportunity and treatment can be reviewed.

Finally, beta-blockers carry the usual risks of ocular irritation and injection as with any preserved topical drug preparation. In recent years, preservative-free versions have been developed, including some preservative-free combinations with PGAs and with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs.)

Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) are another group of medications which reduce IOP by dampening the rate of aqueous production. Carbonic anhydrase is an enzyme found within the red blood cells of the ciliary body. Inhibition of this enzyme reduces bicarbonate formation which is involved in the production of aqueous. Interestingly, CAIs have a similar effect in the kidneys, so these have to be used with caution in patients with renal conditions.

CAIs can be used in glaucoma management in either a topical eye-drop form or in tablet form to be taken orally. CAIs are also to be found in combination products, typically with a beta-blocker or an alpha-agonist, and some topical CAIs are available in a preservative-free option. Examples of topical CAIs include:

- Brinzolamide

- Dorzolamide

CAIs are often used as a second or third line treatments, in a similar fashion to beta-blockers. Usually, the choice between a CAI or a beta-blocker will be down to the individual patient and which of these would be most suitable (or least likely to trigger and adverse response). CAIs have similar IOP lowering properties to beta-blockers, and can achieve an approximate reduction of 15 to 20% from baseline.

The CAI that is administered orally is acetazolamide. This tends to be given in very specific circumstances, and only intended for short-term use due to its risk of side effects. These are various and many and, as the drug readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, include CNS adverse responses. Adverse effects may include:

- Dizziness or light-headedness

- Increased urination

- Blurred vision

- Dry mouth

- Drowsiness and tiredness

- Loss of appetite

- Stomach upset

- Headache

- Pins and needles in the hands and feet

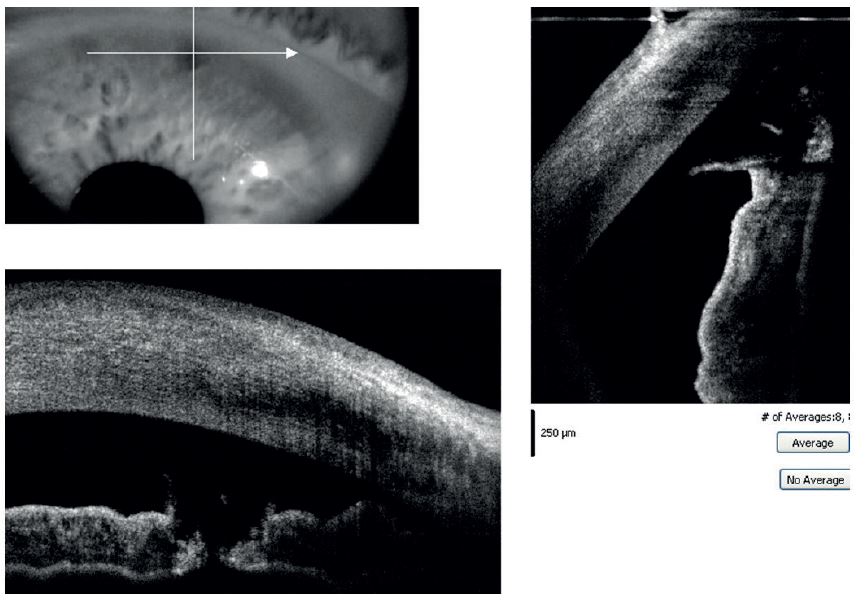

In situations where a rapid reduction in IOP is required, such as during an attack of angle closure glaucoma or with a central retinal artery occlusion (figure 3), acetazolamide is appropriate. In emergency situations it is often administered intravenously.

Figure 3: Acetazolamide may prove useful in the management of retinal artery occlusion

When a patient is on maximum topical medication dosage and their glaucoma still progresses, they might be put on oral acetazolamide to tide them over until surgery can be performed. Some surgeons may also use the drug in the lead up to a trabeculectomy to give the eye a rest from topical eyedrops and with the aim of reducing the risk of post-operative inflammation and bleb healing.

Long-term use is avoided due to the potential for reduced kidney function – and should be avoided completely in patients with known kidney problems. Kidney function needs to be monitored whenever acetazolamide is used for any significant duration. The drug may also interfere with the metabolism of other medications.

Topical use of brinzolamide or dorzolamide may potentially cause similar side effects as those mentioned previously. However, this is much less likely due to the much smaller concentration of medication reaching beyond the eye, so are considered as safe to use long-term as any other topical preparation.

Patients sometimes describe an unpleasant taste in their throat after instilling topical CAIs, so it is good practice to apply a bit of punctal pressure after taking these drops (figure 4).

Figure 4: Topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may cause an unpleasant taste which can be reduced by pressure on the lower punctum

There are reported cases of patients developing low mood or depression with topical CAIs, so it is worth being aware of this and prepared to intervene if the patient reports any such symptoms. Similar to other topical agents, their use may cause stinging, irritation and redness. Dorzolamide is a lower pH preparation than brinzolamide so can often cause more stinging on instillation. However, the drug is now available in a preservative-free form that seems to be tolerated much better.

Alpha-Agonists

The final group of topical agents, alpha-agonists are the third group of agents that lower IOP by reducing aqueous production. The exact mode of action is not fully known. However, it is thought that they cause vasoconstriction within the ciliary body which restricts the output of aqueous. It is also thought that topical alpha-agonists may promote a small increase in uveoscleral aqueous outflow.

There are two topical alpha-agonists currently in use:

- Aproclonidine

- Brimonidine

Apraclonidine is not a preparation that tends to be used for long-term treatment because of its side-effect profile. However, in a way similar to acetazolamide, it has a significant role in bringing about significant reductions in IOP over a short period of time in very specific situations. The main such use is before and after glaucoma-treating laser procedures, such as peripheral iridotomy or selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) where it helps to prevent IOP spikes (figure 5).

Figure 5: Alpha-agonists are useful before or after laser treatments for glaucoma, such as peripheral iridotomy as shown here

Apraclonidine carries a high risk of allergic reaction if used for any longer period. It can cause dryness of the oral and nasal mucosa, and around 5 to 10% of patients feel fatigue due to the drug, so it is generally only used in these specific circumstances.

Brimonidine is suitable for longer-term topical treatment, and tends to be used as a third or fourth line option once other class of drugs have been explored. The drug may be used on its own, but is also available in a combination with brinzolamide or with the beta-blocker levobunolol (a preparation known as Betagan).

Compared with apraclonidine, its side-effect profile is less concerning as brimonidine is a much more selective agent. However, it can be prone to causing a hypersensitivity reaction within the eye so tends to be the last line of treatment. This type of reaction can develop months after starting treatment with the drop, the patient developing a very red, itchy or burning eye. Where this occurs, use of the drug needs to be discontinued and it is always worth pre-warning patients that this may happen and to report it when it does. The British National Formulary (BNF) reports various other side-effects, including:

- Dizziness

- Sleep disturbance

- Dry mouth

- Malaise

However, the most common adverse response remains the localised reaction. Despite the side effects, brimonidine is still a useful option and may help in controlling a patient’s IOP and prevent them requiring surgery. There is also some evidence to suggest that this drop has a neuro-protective effect, so can be useful in normal tension glaucoma patients who are showing signs of progression.

Summary

The past 25 years has seen a tremendous advance in the availability of medications for the treatment of glaucoma. As clinicians, we have a wide choice of products to choose from when treating our patients and, in each case, it is a matter of trying to establish the best drop or combination of drops that controls the glaucoma while minimising unwanted side-effects for the patient.

This article may read like a list of the potential negative aspects of these drugs. However, most patients can be successfully treated medically with a regime that suits them. As clinicians, exploring these possible side effects is really important, so we have an awareness of them and can identify patients for whom specific drops are likely to cause adverse reactions, either locally or systemically.

Unfortunately, we can never predict in every case when a patient is going to develop problems with a drug, so it is always good practice to pre-warn patients when starting on a treatment of the potential side effects and give them a means of getting in touch with you if they occur. From a clinician’s perspective, we have to be prepared for patients reporting adverse problems and be able to address them. Obtaining a careful history of their symptoms and how this ties in with the use of their medication is important. You then have to think of the best plan of action to resolve these issues. This might include:

- Stopping use of the drug altogether

- Prescribing an alternative drug or class of drug

- Considering unpreserved versions of the same drug

- Considering other treatment modalities (such as laser or surgery) in cases where all possibilities have been explored in the face of progressing disease.

Stanley Keys is a hospital optometrist based at Raigmore Hospital in Inverness where he is involved in glaucoma clinics, cataract assessments and specialist contact lens practice