The current situation

Prevalence

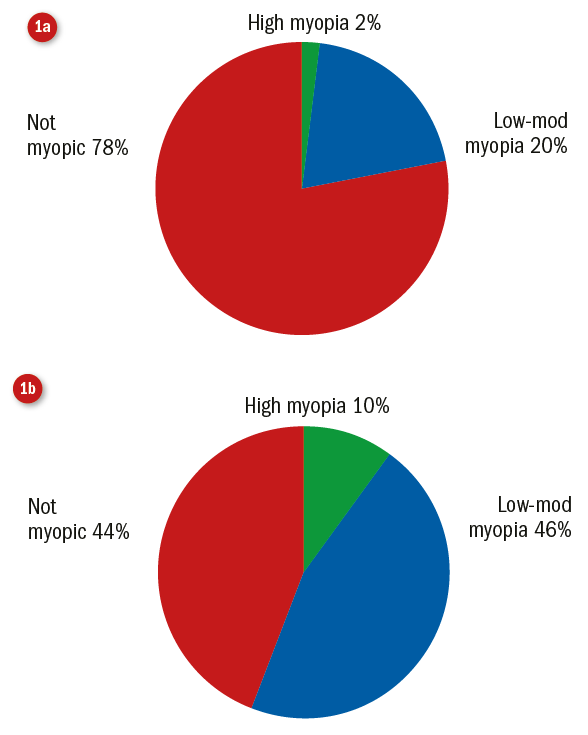

There is an optometry related statistic, one which many readers will have heard before, that by the year 2050 almost half of the world’s population (49.8%) will be myopic. Perhaps a more relevant statistic for UK eye care professionals (ECPs), but one which is less widely circulated, is that by the year 2050 myopia prevalence in Western Europe will have reached 56.2%. So, the predicted figure is not ‘almost’ 50%, but in excess of it (figure 1).

Figure 1: Western European distribution of high, low and no myopia in the year 2000 (a), predicted prevalence of high, low, and no myopia in the year 2050 (b)1

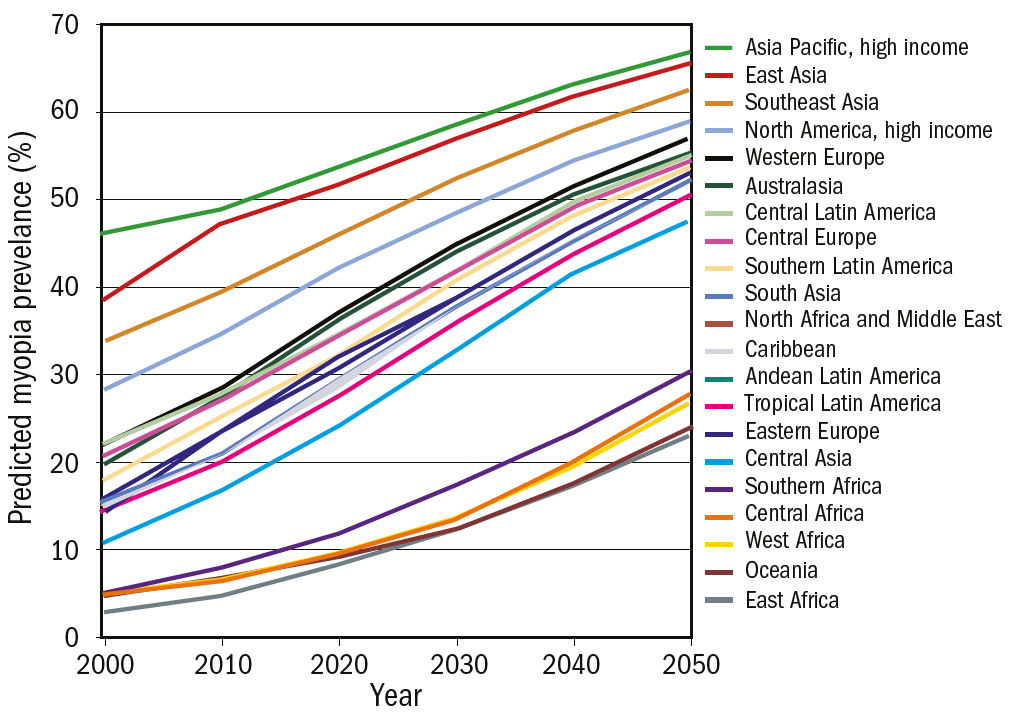

Worldwide, the predicted myopia prevalence statistics paint a bleak picture across the globe (figure 2).

Figure 2: Global myopia prevalence predictions for years 2000-2050 1

While predictions show that areas such as East Asia will continue to be some of the worst affected in terms of overall myopia prevalence, even areas which have historically had lower myopia prevalence have cause for concern. For instance, consider the impact upon areas such as East Africa, where an approximate seven-fold increase in myopia prevalence is predicted over a 50 year period. The likely increase in need for ECPs, demand for refractive correction, and management of associated ocular pathologies are just some of the considerations which will need to be taken into account when allocating future healthcare resources.

Myopia and axial length

Typically, increasing myopia is accompanied by a corresponding elongation of axial length. That 1mm increase in axial length equates to approximately 3.00 DS of myopia is a compelling statistic. Myopia is a lifelong condition; axial elongation of 1mm can dramatically impact a patient’s life, for life.

Myopia and pathology

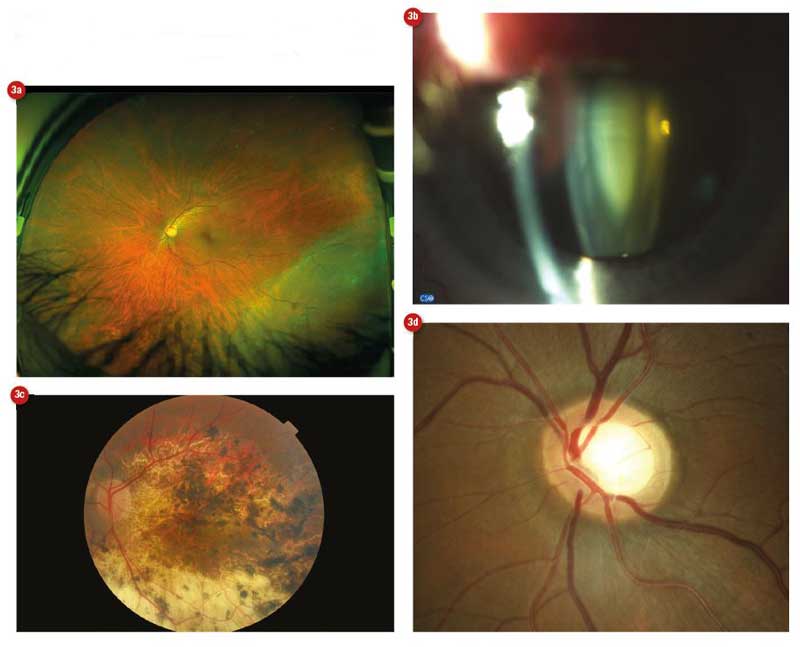

Structural changes are not, however, limited to the axial dimension, changes can occur in the eye height, width, and to the overall shape of the eyeball.2-4 Myopia is also associated with an increased risk of retinal detachments, nuclear cataracts, myopic maculopathy and other ocular pathologies (figure 3).5-7 A number of myopia related pathologies are reported to be ‘dose-dependent’ in that the greater the level of myopia, the greater the risk of developing the pathology. Thus, impeding the progression of myopia such that it is retained at lower levels should reduce the overall risk of developing pathology.

Figure 3: Myopia is associated with an increased risk of a range of ocular diseases, including (a) retinal detachment, (b) cataract, (c) myopic maculopathy and (d) glaucoma

Why is there a global increase in myopia?

While a comprehensive review of the theories underlying the recent increase in myopia prevalence is outside the scope of this article, it is worth mentioning that environmental factors, such as increased close work and reduced time outdoors, have been linked to myopia development.8-10 Minimising peripheral hyperopic defocus and reduction of accommodative lag are two popular approaches underpinning the design of several myopia control therapies.

Optometry workforce

Numerous therapies have been developed to combat the increasing levels of myopia.11 While not all therapies are commercially available across the world, most ECPs are able to access at least some form of therapy or provide advice to patients. Anecdotally, there appears to be a great deal of ECP interest in myopia control, however, such interest has not necessarily translated into uptake.12

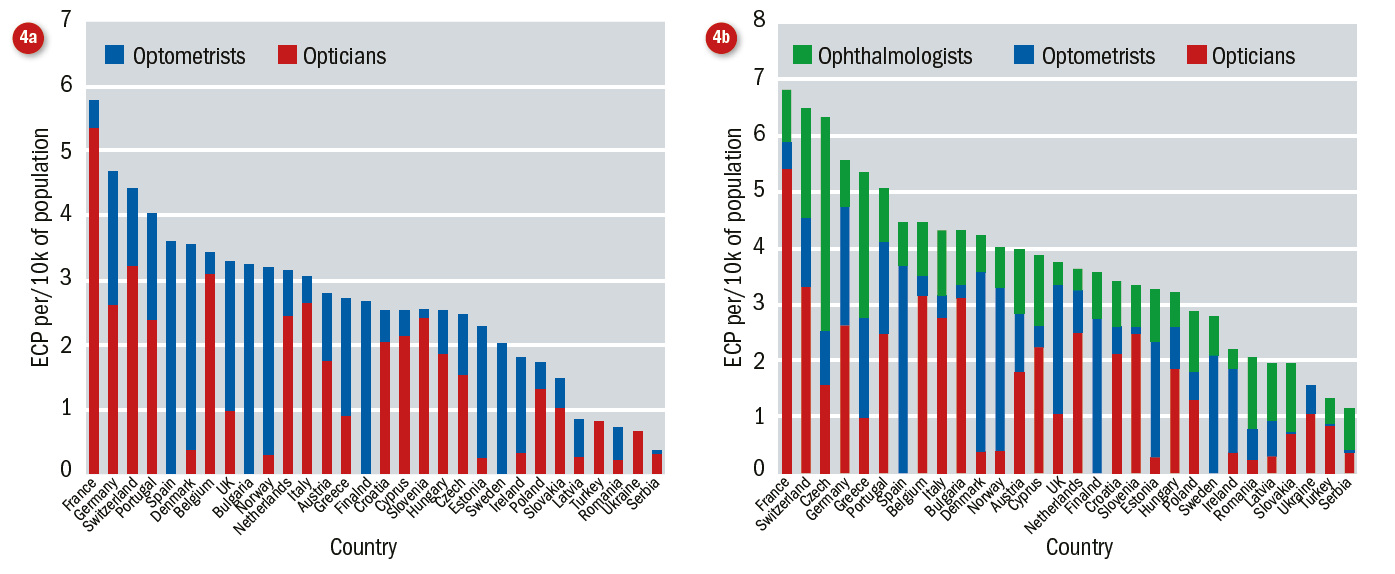

To understand the potential for myopia control, it is helpful to consider the landscape of ophthalmic care provision in the UK and beyond. According to data compiled by the European Council of Optometry and Optics, the UK has over 15,000 optometrists and more than 6,500 opticians; collectively this represents one of the larger optical workforces (opticians and optometrists) in Europe (figure 4).

Figure 4: European eye care professionals. (a) Optical workforce comprising opticians and optometrists; (b) the optical workforce comprising opticians, optometrists and ophthalmologists (source: ECOO blue book)

The roles and responsibilities of an optometrist, optician, and ophthalmologist are not, of course, equivalent across Europe; there are significant differences in the scope of practice for each ECP. Nevertheless, there appears to be a reasonably healthy workforce for providing myopia control, so what could be causing practitioner hesitance?

Barriers to myopia control uptake

Stakeholders

When considering myopia control prescribing patterns, the focus is generally on the practitioner.12 The practitioner is, however, only one part of the process. There are multiple stakeholders, including:

- Manufacturers and marketers of therapies

- Researchers involved in product development and trials

- The practice in which an ECP works

- The patient (and parent)

Each stakeholder will have their own set of objectives or level of interest with respect to the myopia control process, their respective levels of influence on the process of myopia control will also differ. For example, a practice owner may have low interest in myopia control. As a result, the myopia control provisions offered by an ECP working in the practice may be limited by an absence of senior buy-in. This might be reflected in, for example, lack of investment in a corneal topographer. This in turn might prevent an otherwise willing ECP from offering orthokeratology.

Diffusion of innovation

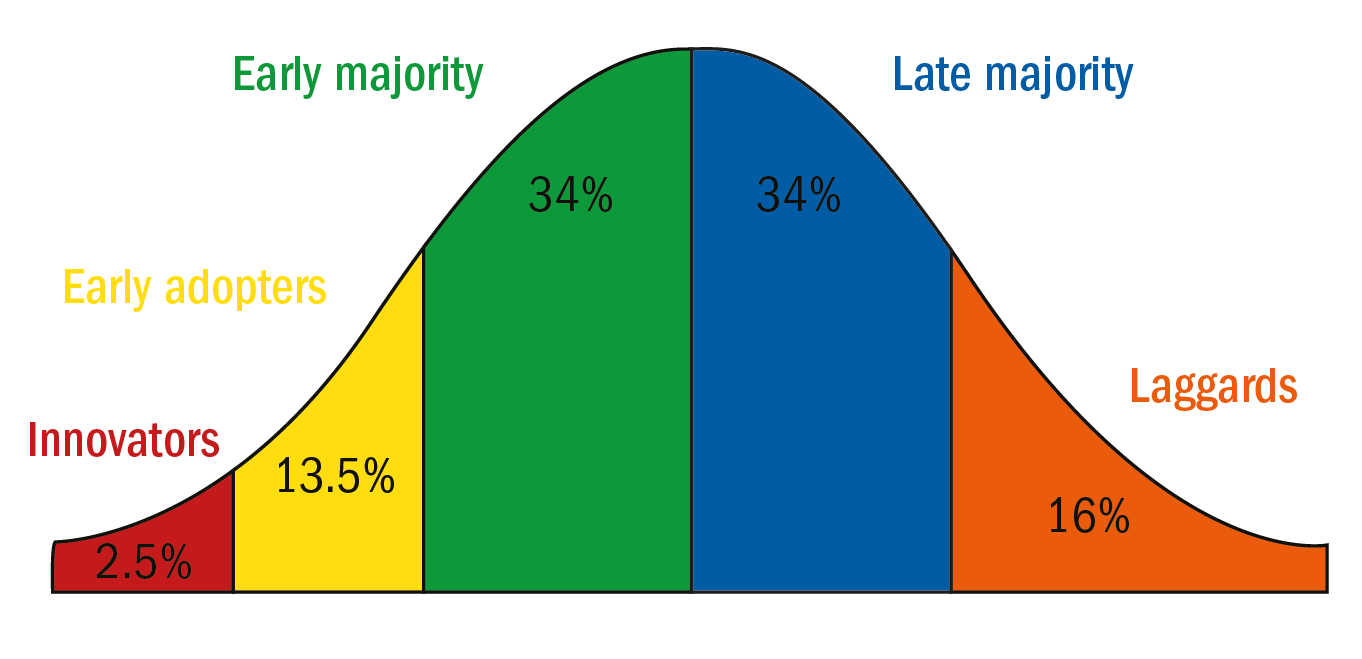

While there are gaps in the research, and therefore in our knowledge, of myopia control and such concerns are reflected in professional guidance; the diffusion of innovation theory describes how, over time, a product or an idea spreads across a specific population.13 Rogers popularised the theory, describing five groups of people, each demonstrating different levels of readiness with regards to adopting new technologies (figure 5). The model emphasises the importance of communication channels in the diffusion of technology.

Figure 5: Roger’s diffusion of innovation categories with estimated percentage of adopters for each group

Figure 5: Roger’s diffusion of innovation categories with estimated percentage of adopters for each group

When a new technology is introduced, we may initially see a peak in interest. This initial ‘hype’ is likely to be led by the group termed ‘innovators’. Innovators are described as being venturesome. Such individuals are interested by new products or ideas, they are perhaps the sort of individuals who would have embraced the 1980s Sinclair C5 or relished the chance to own the early ‘brick’ mobile phones. Their interest in new ideas moves them out of their local peer networks to developing more cosmopolite social relationships.14 Innovators typically have the means to take on greater financial risks.

The next group, the ‘early adopters’ need little convincing as they are already willing to adopt new ideas, typically this group will represent opinion leaders or those in leadership roles with a desire to be trend setters.

The ‘early majority’ will be more cautious than the innovators and the early adopters, they may want to see evidence prior to adopting a new idea. Although the early majority are willing to adopt innovations before the average person, they will rarely lead on embracing new technologies.

The last two groups may have low tolerance for economic risk. The ‘late majority’ will typically only adopt a new idea after the average member of a population and once the risks associated with adopting an idea have been minimised; they are responsive to peer pressure and economic necessity. The final group is termed the ‘laggards’ and considered to have a conservative or sceptical outlook. The laggards tend to make decisions based on what has worked in the past and have little interaction with opinion leaders.14,15

Rogers outlines different approaches when appealing to each of the five groups. With respect to optometry, we may conclude that not every ECP is looking for the same information and assurances. We cannot expect all ECPs to embrace innovations with the same level of interest and enthusiasm. Factors such as ability to withstand economic risk may play a role in an individual’s decision to adopt new technologies.

Practitioner perspectives

A worldwide survey published in 2016 considered the views of ECPs (n=971) with respect to myopia control. Responses from Asia, Europe, Australasia, North and South America were reported. Survey respondents were mainly optometrists (72.4%) and ophthalmologists (18.6%) and the majority worked in clinical practice (84.4%). The study outcomes showed that despite concern among ECPs about increasing paediatric myopia (concern was scored as a median 7/10 for all continents included in the study except Asia, where concern was higher at a median 9/10), over two-thirds of practitioners (68%) continued to prescribe young/progressing myopes single vision contact lenses or spectacles. The report also found myopia control was not introduced early enough in a child’s ocular development, thus limiting its usefulness.

The survey highlighted some education issues: respondents correctly considered orthokeratology to be one of the most effective methods of myopia control but underestimated the effectiveness of pharmaceutical methods and overestimated the effect of time outdoors on myopia. The main reasons preventing practitioners from undertaking myopia control differed across continents; for example, concerns about inadequate information were most common among European practitioners, but in Asia the primary concern was safety. Other reasons for not

undertaking myopia control included: unpredictable outcomes; a belief that myopia control methods were not effective; the limited availability of products; and limited access to necessary instrumentation.12

Uptake of myopia control

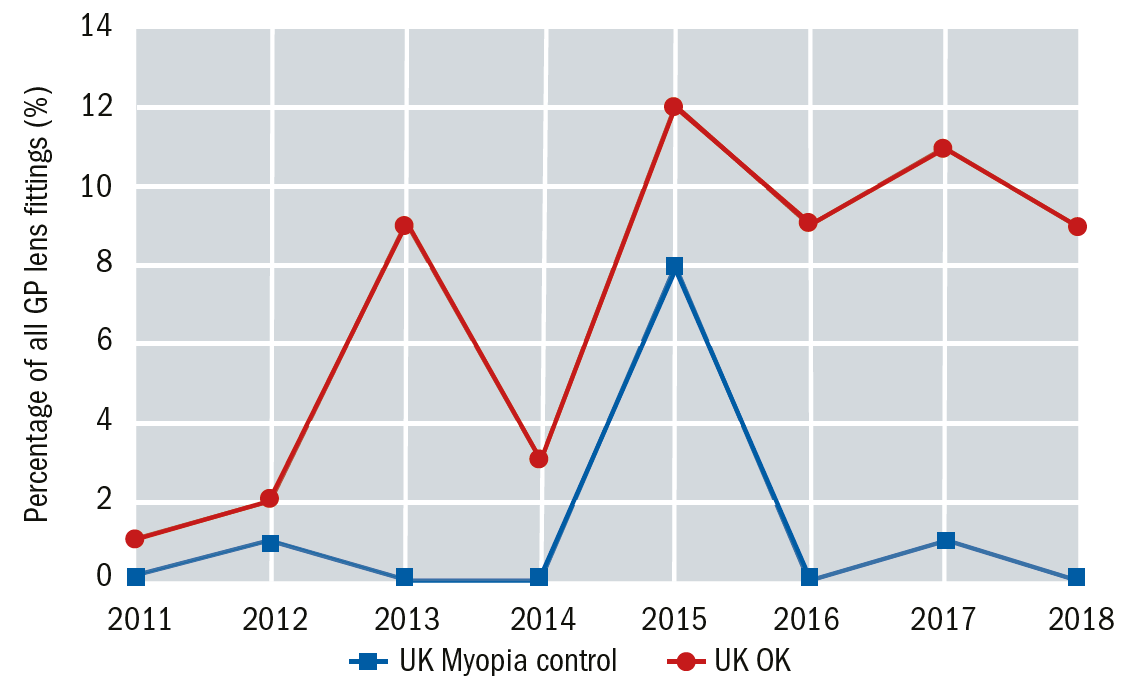

Figure 6 shows the percentage of orthokeratology fittings and ‘myopia control’ fittings out of the total rigid lens fittings in the UK (using data from Morgan et al).

Figure 6A: Annual percentage of orthokeratology (red) and GP myopia control fittings (blue)16 out of all GP lens fits. GP lenses (all types) accounted for approx. 4% of all contact lens fittings in the UK in 2018

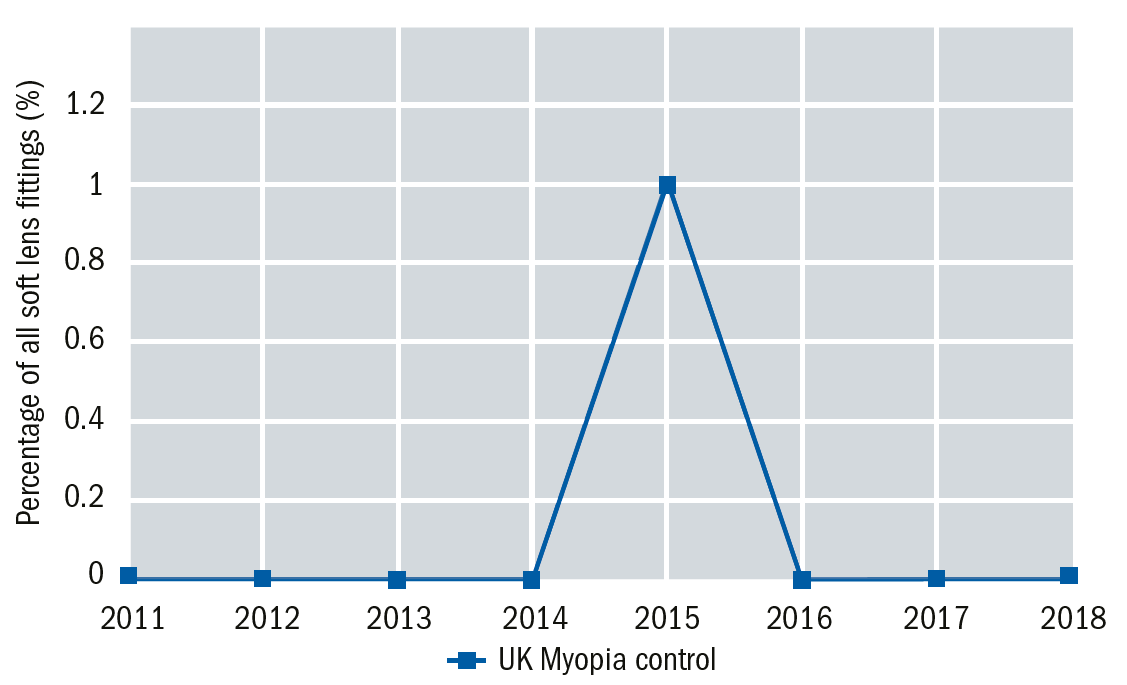

Figure 6B: Annual percentage of soft lenses fitted for myopia control (blue) out of all soft lens fits. Soft lenses (all types) accounted for approx. 96% of all contact lens fittings in the UK in 2018

Despite some annual fluctuations, there appears to be a general increase in orthokeratology (OK) prescribing. While these data are likely to include individuals who have chosen OK as an alternative to spectacles or daily lens wear, the rise in fittings may at least in part be attributed to growing interest in myopia control. The percentage of soft contact lens fittings for myopia control, appear to have remained steady except for a peak in 2015. Given the recent introduction of MiSight, a licensed soft daily disposable lens for myopia control, which has recently been stocked by a multiple, we may see the soft lens myopia control market regain momentum in the near future.

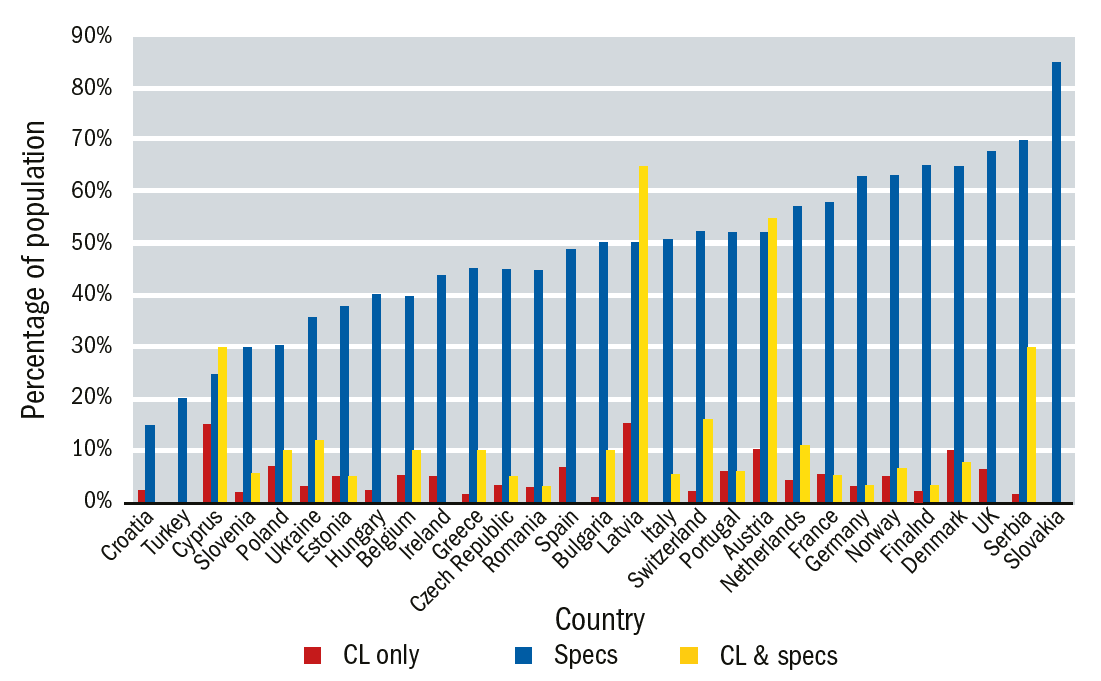

Nevertheless, it is worth considering that while there are approximately 3.7 million contact lens wearers in the UK (less than 6% of the population) and approximately 10% of these are children and teenagers,17 the contact lens market is still relatively small compared to the spectacle lens market. Practitioners appear to be more willing to adopt spectacle lens-based myopia solutions with younger children, compared to contact lenses. Wolffsohn et al12 reported that multifocal spectacle solutions were, on average, prescribed to children age six to seven years old (bifocals, 6.3 ±2.3 years; PALs, 7.3 ±2.8 years) whereas average age for myopia control contact lens solutions was around eight to nine years (orthokeratology, 8.8 ±3.1 years; novel soft myopia control lenses, 8.8 ±3.1 years; multifocal, 8.9 ±3.1 years). Figure 7 shows spectacle and contact lens wear across Europe, not just that relating to myopia control.

Figure 7: Spectacle and contact lens wear(not just relating to myopia) in Europe (source ECOO blue book)

Practice

Senior buy-in from employers may also influence prescribing decisions. Morgan and Efron18 found contact lens fitting behaviour to be influenced by practice setting. They reported that those working in independent practices prescribed more extended wear and multifocal lenses, but tended to fit fewer soft, soft torics, and daily disposables.

With respect to myopia control, senior buy-in may be a prerequisite for some types of therapies, particularly those which require changes to practice infrastructure. Perhaps a good way of illustrating the impact of senior buy-in is through the recent example of OCT introduction into Specsavers practices. Press reports indicate that prior to the senior buy-in, only around 20 to 35 of Specsavers’ 740 practices had OCT. They report that within days more than half of practices had expressed interest and now Specsavers are aiming to have an OCT in every practice by early 2020.19-21

Patients and parents

McCann et al22 found that 46% of parents viewed myopia as a health risk and the same percentage viewed it as an optical inconvenience. Just under a third (31%) viewed myopia as an expense, while only 14% considered it a cosmetic inconvenience. No significant differences were found between the lifestyles of parents who considered myopia a health risk and those who did not.

However, parental intervention, when applied, can be effective in controlling myopia onset. Zhou et al23 found parents of non-myopic children paid greater attention to introducing myopia-inhibiting activities when compared to parents of myopic children. Positive parental intervention was found to significantly lower the risk of myopia.

Bring about change

While there are still aspects of myopia control which remain uncertain and research is needed to establish the longer-term effects of some myopia control treatments, we do have data showing us the negative impact of myopia, data showing us that myopia can be inhibited, and most recently, the introduction of a licensed myopia control product. Is there likely to be a cultural shift among ECPs, with regards to myopia control?

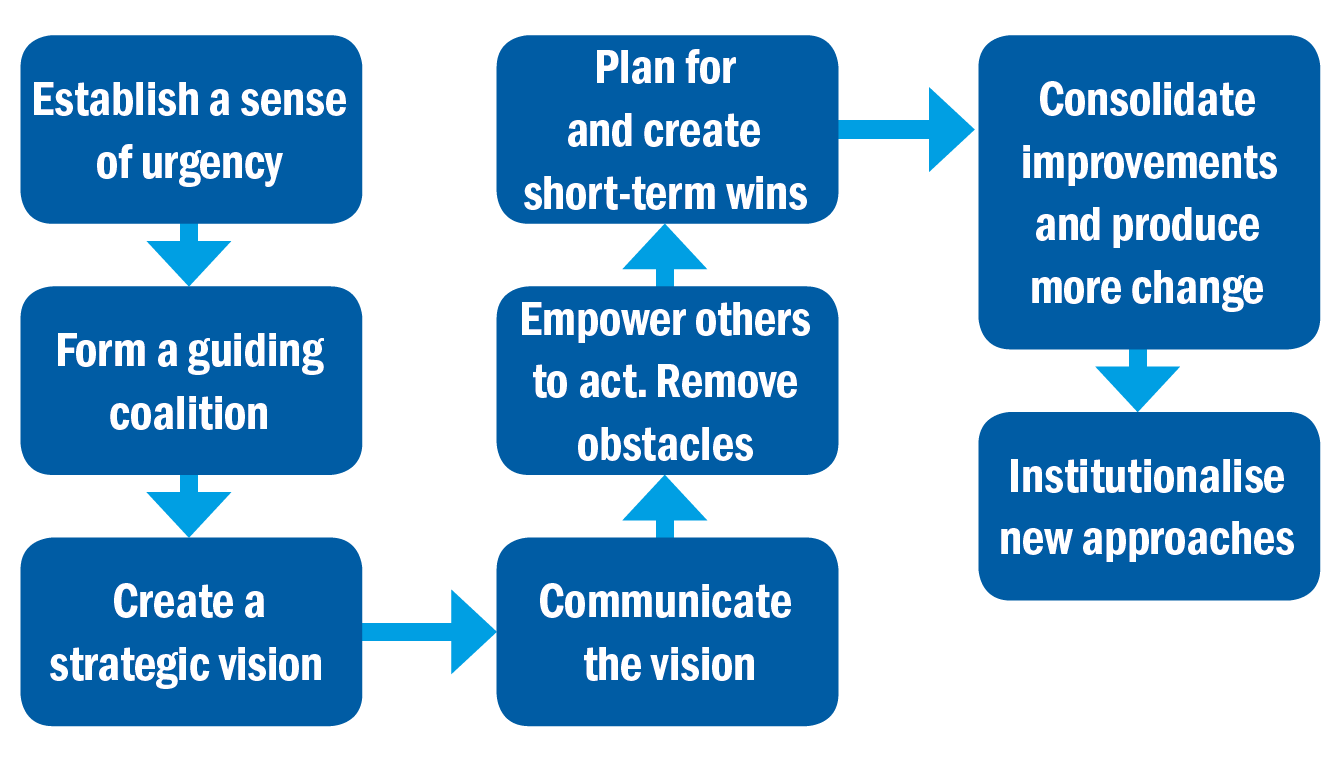

Numerous models of change exist. One well known model is Kotter’s eight-step process for change. The steps are shown in figure 8 and as an example, the MiSight journey could be mapped onto these steps.24,25 Based on information in the public domain, the multi-centre clinical trial could be said to represent the ‘guiding coalition’ as could those involved in the initial limited release of the lens. The ‘vision’ has been communicated and marketed through various optical press and educational channels. Regulatory approval of the product and developments in professional guidance demonstrate a removal of ‘obstacles’. Short term wins have included a national award, but whether an introduction of the lens into a large multiple indicates the start of institutional change remains to be seen.

Figure 8: Kotter’s eight-step process for change

There will, however, always be external factors which influence the uptake of any technology. If we undertook a simple PESTLE analysis, considering the:

- Political

- Economic

- Social

- Technological

- Legal

- Environmental influences...

then additional factors can be identified. One of the current issues in health is that of health inequalities. Does introducing a service such as myopia control, which may be the preserve of those who have the means to pay, exacerbate existing health inequalities? Will children from poorer economic backgrounds grow to be adults with a greater risk of myopia related pathologies simply because their parents could not afford to impede their escalating myopia? Popularity of such therapies can also be influenced by other social factors: parental education, national campaigns, a celebrity endorsement. As technologies develop, costs decrease and user friendliness increases, we may see myopia control become more accessible for both practitioners and patients.

Summary

Multiple stakeholders are involved in myopia control. Information and education should address concerns of all groups and include clarification of common misunderstandings.

Published data shows spectacle lenses tend to be prescribed at an earlier age than contact lenses and that type of practice setting can influence prescribing patterns. Practitioners are concerned about issues such as safety, lack of information, and effectiveness. Based on such findings it seems an ideal therapy is a simple optical solution, one with senior buy-in, low clinical risks, and long-term safety and efficacy data.

Dr Manbir Nagra is a Reader in Optometry at the University of Portsmouth and works as a consultant in the optometric sector.

References

- Holden, B.A., Fricke, T.R., Wilson, D.A., Jong, M., Naidoo, K.S., Sankaridurg, P., Wong, T.Y., Naduvilath, T.J. and Resnikoff, S., 2016. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology, 123(5), pp.1036-1042.

- Atchison, D.A., Jones, C.E., Schmid, K.L., Pritchard, N., Pope, J.M., Strugnell, W.E. and Riley, R.A., 2004. Eye shape in emmetropia and myopia. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 45(10), pp.3380-3386.

- Gilmartin, Bernard, Manbir Nagra, and Nicola S. Logan. Shape of the posterior vitreous chamber in human emmetropia and myopia. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 54.12 (2013): 7240-7251.

- Hsiang, H.W., Ohno-Matsui, K., Shimada, N., Hayashi, K., Moriyama, M., Yoshida, T., Tokoro, T. and Mochizuki, M., 2008. Clinical characteristics of posterior staphyloma in eyes with pathologic myopia. American journal of ophthalmology, 146(1), pp.102-110.

- Younan, C., Mitchell, P., Cumming, R.G., Rochtchina, E. and Wang, J.J., 2002. Myopia and incident cataract and cataract surgery: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science, 43(12), pp.3625-3632.

- Kubo, E., Kumamoto, Y., Tsuzuki, S. and Akagi, Y., 2006. Axial length, myopia, and the severity of lens opacity at the time of cataract surgery. Archives of Ophthalmology, 124(11), 1586-90.

- Saw, S.M., Gazzard, G., Shih Yen, E.C. and Chua, W.H., 2005. Myopia and associated pathological complications. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 25(5), pp.381-391.

- Huang, H.M., Chang, D.S.T. and Wu, P.C., 2015. The association between near work activities and myopia in children—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 10(10), p.e0140419.

- Sherwin, J.C., Reacher, M.H., Keogh, R.H., Khawaja, A.P., Mackey, D.A. and Foster, P.J., 2012. The association between time spent outdoors and myopia in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 119(10), pp.2141-2151.

- Wu, P.C., Tsai, C.L., Wu, H.L., Yang, Y.H. and Kuo, H.K., 2013. Outdoor activity during class recess reduces myopia onset and progression in school children. Ophthalmology, 120(5), pp.1080-1085.

- Huang, J., Wen, D., Wang, Q., McAlinden, C., Flitcroft, I., Chen, H., Saw, S.M., Chen, H., Bao, F., Zhao, Y. and Hu, L., 2016. Efficacy comparison of 16 interventions for myopia control in children: a network meta-analysis. Ophthalmology, 123(4), pp.697-708.

- Wolffsohn, J.S., Calossi, A., Cho, P., Gifford, K., Jones, L., Li, M., Lipener, C., Logan, N.S., Malet, F., Matos, S. and Meijome, J.M.G., 2016. Global trends in myopia management attitudes and strategies in clinical practice. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 39(2), pp.106-116.

- Rogers, E.M., 2002. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addictive behaviors, 27(6), pp.989-993.

- Rogers, E.M., 2010. Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster.

- Kaminski, J., 2011. Diffusion of innovation theory. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 6(2), pp.1-6.

- Morgan et International contact lens prescribing, 2012-2019, Contact Lens Spectrum, volume: 27, issue: January 2012, page(s): 26 - 32, volume: 28, issue: January 2013, page(s): 31 - 38 44, volume: 29, issue: January 2014, page(s): 30 - 35, volume: 30, issue: January 2015, page(s): 28-33, volume: 31, issue: January 2016, page(s): 24-29, volume: 32, issue: January 2017, page(s): 30-35, volume: 33, issue: January 2018, page(s): 28-33, volume: 34, issue: January 2019, page(s): 26-32

- Efron, N., Morgan, P.B., Woods, C.A. and International Contact Lens Prescribing Survey Consortium, 2011. Survey of contact lens prescribing to infants, children, and teenagers. Optometry and Vision Science, 88(4), pp.461-468.

- Morgan, P.B. and Efron, N., 2015. Influence of practice setting on contact lens prescribing in the United Kingdom. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, 38(1), pp.70-72.

- https://www.aop.org.uk/ot/industry/high-street/2017/09/29/specsavers-announces-oct-partnerships

- https://www.aop.org.uk/ot/industry/high-street/2018/11/19/an-oct-in-every-store-by-2020

- https://www.aop.org.uk/ot/industry/high-street/2017/05/22/oct-rollout-in-every-specsavers-announced

- McCrann, S., Flitcroft, I., Lalor, K., Butler, J., Bush, A. and Loughman, J., 2018. Parental attitudes to myopia: a key agent of change for myopia control?. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 38(3), pp.298-308.

- Zhou, S., Yang, L., Lu, B., Wang, H., Xu, T., Du, D., Wu, S., Li, X. and Lu, M., 2017. Association between parents’ attitudes and behaviors toward children’s visual care and myopia risk in school-aged children. Medicine, 96(52), pp.e9270-e9270.

- Kotter, J.P., 1995. Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail.

- Kotter, J.P., 2012. Leading change. Harvard business press.