Glaucoma is a progressive, multifactorial disease that causes damage to the retina and optic nerve causing an insidious loss of vision and, if left untreated, results in irreversible sight loss and blindness. Indeed, the condition has been the cause of around 12 per cent of sight loss registration in the UK for many years.

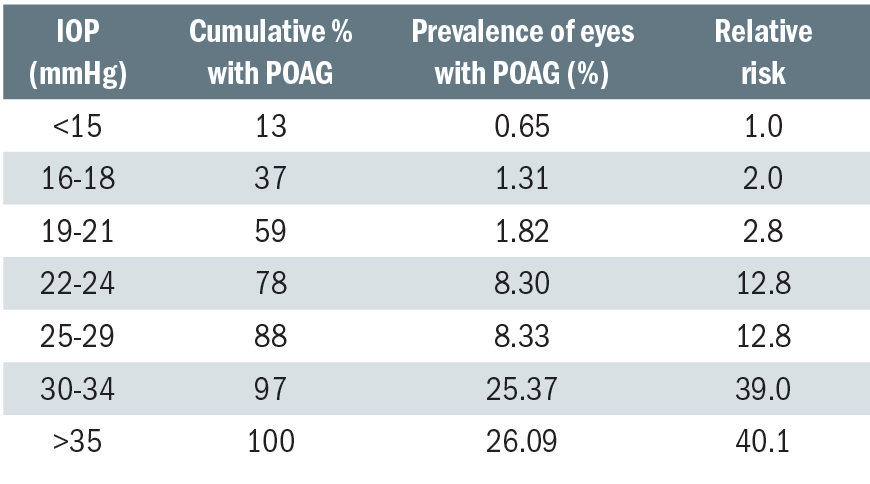

Of the many forms of chronic or acute forms of open or closed angle glaucoma, the commonest is primary open angle glaucoma (OAG). The greatest risk factor for OAG is age, with around two per cent of the population aged over 40 years affected by the disease in the UK, but there is also a strong association with intraocular pressure. It is the lowering of intraocular pressure (IOP) that is the only currently available treatment for glaucoma and slows down further progression of the disease. Many patients present with raised IOP but without optic nerve damage, and this is termed ocular hypertension. Many ocular hypertensives convert to glaucoma, and so lowering their IOP helps reduce the risk of the disease establishing (see table 1). The way this is undertaken may be undergoing a major change in light of the recently published LiGHT (Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension).1

Table 1: Prevalence of POAG at different levels of screening IOP and the relative risk at specific levels of IOP2

Current Treatments

At present, the mainstay of treatment to lower IOP is the use of a range of topical drops. For a review of these, see Optician 01.03.19. There are also a range of surgical and laser techniques used variously in IOP management. Surgical techniques include:

- Trabeculectomy – creation of a filtration channel via the sclera to allow aqueous outflow to the subconjunctival space.

- Non-penetrating surgery – techniques such as deep sclerectomy, viscocanalostomy and canaloplasty attempt to avoid or limit the production of a filtration bleb by improving aqueous outflow via Schlemm’s canal.

- Aqueous drainage implants – more commonly performed in individuals with secondary glaucoma, or when other glaucoma treatments or operations have previously been unsuccessful.

The development of lasers has had a major impact on the medical management of IOP. Laser treatments include:

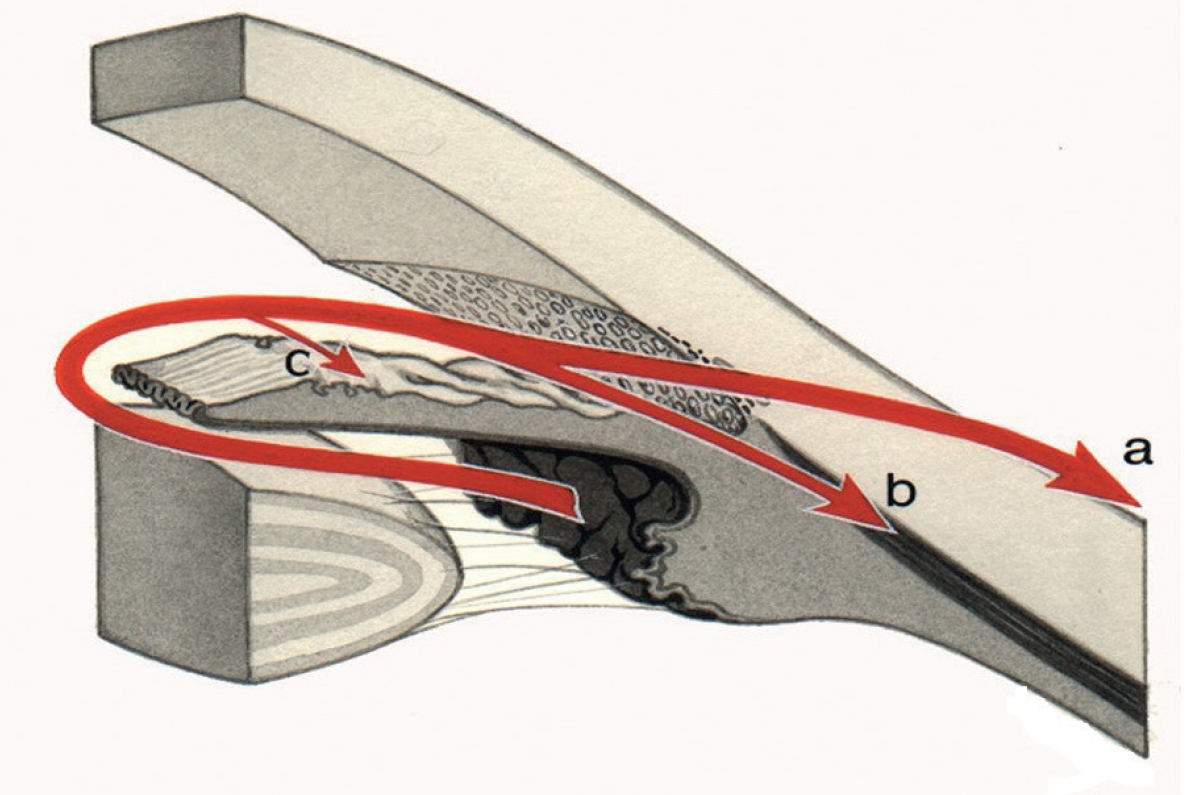

- Laser trabeculoplasty (LT) – there are different types of LT (see later), but all are designed to burn the trabecular meshwork outflow route (figure 1) to enhance aqueous outflow.

- Iridotomy – an Nd:YAG laser can be used to ‘open’ a ‘narrow’ or ‘occludable’ angle by creating a hole in the iris to improve aqueous passage.

- Iridoplasty – performed to the peripheral iris to cause contraction of the peripheral iris stroma away from the angle structures resulting in deepening of the angle recess.

- Cycloablation – the destruction of small areas of the ciliary body which is responsible for producing aqueous humour.

Figure 1: Aqueous outflow routes; (a) uveoscleral, (b) trabecular and (c) iris. SLT facilitates drainage via route (b)

Until now, laser and surgical techniques were generally reserved for those patients unable to be controlled by the less invasive treatments offered by drops. In the short-term, drop use might also be perceived as a cheaper option.

It is thought that around 1 million outpatient visits are made each year in the UK for glaucoma-related appointments. This makes glaucoma the sixth most common reason for outpatient attendance according to underlying condition of any health

problem in the UK. Also, with the disease often presenting in the fourth or fifth decade of life, ongoing monitoring and treatment is a long-term phenomenon and so represents a major cost to health care services in the UK. This is only going to increase under current protocols for management, as life expectancy maintains an upward trend (bar a few recent blips one assumes).

Topical treatment, either single or combination drop therapies, have several disadvantages:

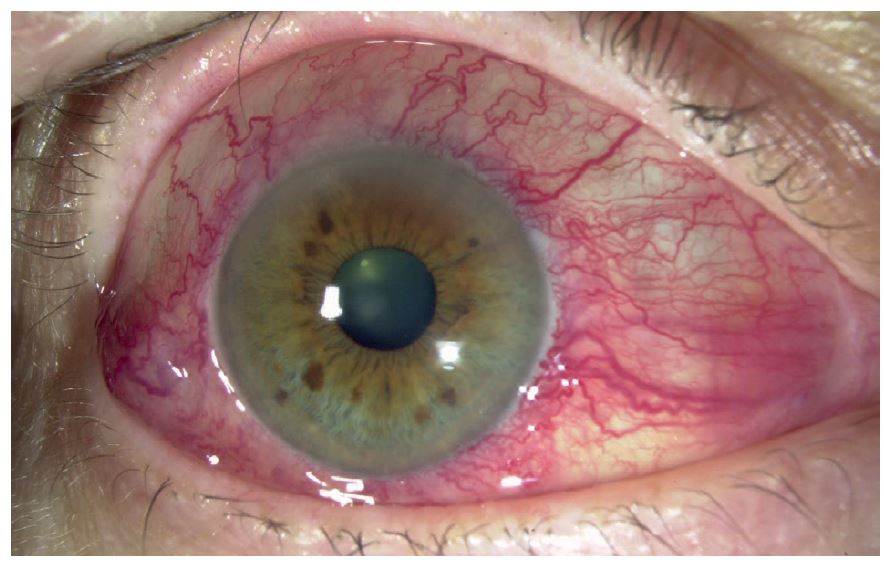

- Multiple ocular and systemic side effects2 – an adverse response to preservatives in preparations is not uncommon, for example (see figure 2), while entry into the systemic vasculature can impact on the whole body.

- Poor patient adherence and compliance – few relish the repeated use of often uncomfortable drop instillation on a regular daily basis indefinitely.

- Patient limitations – the association of glaucoma with increasing age means that many patients have neither the physical nor cognitive ability to use drops on a repeated basis.

Figure 2: Adverse responses to drops are not uncommon

Laser trabeculoplasty

Laser trabeculoplasty has been primarily used to treat open-angle glaucoma. The two commonest types of laser trabeculoplasty used are:

- Argon laser trabeculoplasty (ALT)

- Selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT).

ALT involves the application of argon laser burns to the trabecular meshwork (TM), enhancing aqueous flow, and thus lowering the IOP. ALT’s mechanism of action is believed to result from the mechanical tightening of trabecular tissue, thereby opening adjacent untreated trabecular spaces. It is also thought to induce cell division and migration of macrophages to clear the trabecular meshwork (TM) of debris. It is applied with the help of a goniolens, with the aiming beam focused at the junction of the pigmented and non-pigmented TM. The area of treatment can vary between half (180°) or the whole circumference (360°) of the anterior chamber angle. ALT has been largely superseded by SLT.

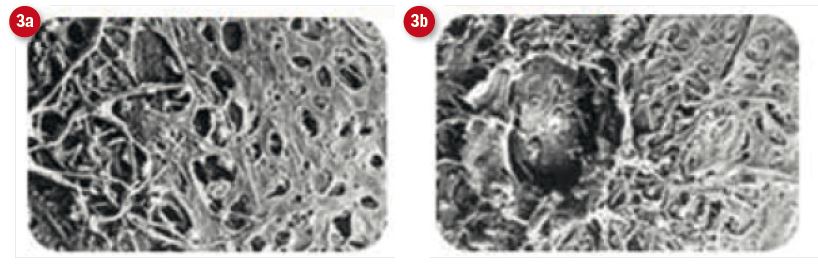

Figure 3: Electron micrsoscopy views of the trabecular meshwork after, (a) SLT and (b) ALT. Note the more benign nature of SLT intervention4

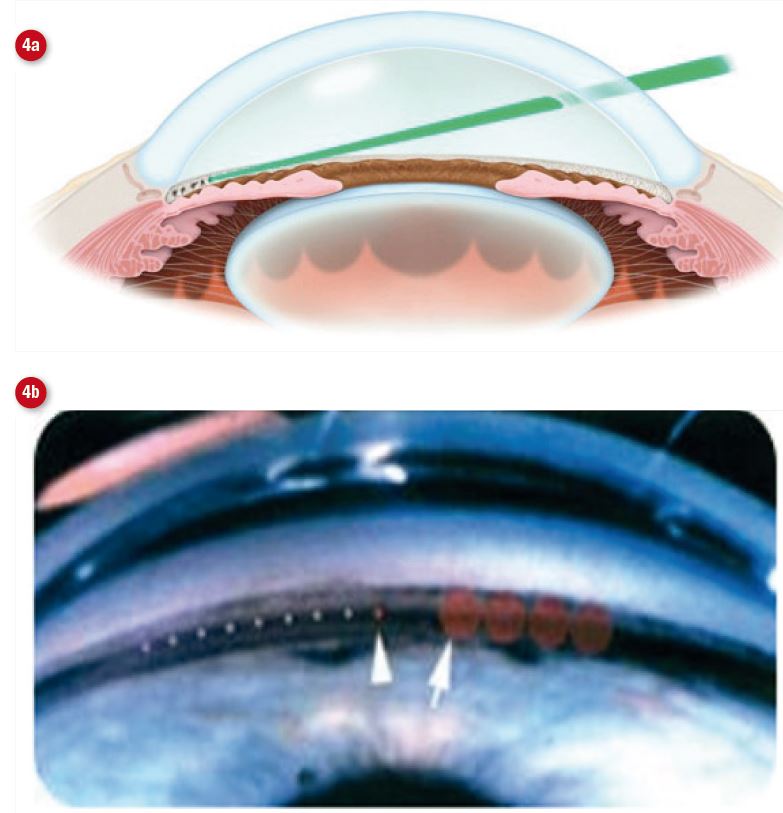

SLT utilises a Nd:YAG laser which selectively targets the melanin pigment in the TM cells, sparing non-pigmented structures (figure 3). It provides easier targeting compared to the ALT apparatus, is reported to have a lower side effect profile due to the lower amount of laser energy used in treatment and has been shown to be as effective as ALT (figure 4).3,4

Figure 4: Selective laser trabeculoplasty involves the use of a contact lens to (a) focus a laser onto the trabecular meshwork. (b) shows the relative spot size with ALT (left arrow) and SLT (right arrow)

MicroPulse laser trabeculoplasty (MLT) is a more recent method using the IRIDEX IQ 532 and is reported to be equivalent to ALT and SLT in lowering IOP.5

Both ALT and SLT are indicated for the treatment of ocular hypertension, primary open angle and secondary open angle glaucomas, such as pseudoexfoliation and pigment dispersion glaucoma. Steroid induced glaucoma is another possible candidate for the procedure. Narrow angle glaucoma, where the trabecular meshwork is not obstructed by iris apposition or synechiae, may also benefit. If there is synaechial closure, trabeculoplasty is not advised. Contraindications are inflammatory, iridocorneal endothelial (ICE) syndrome, developmental, and neovascular glaucoma. Laser trabeculoplasty is also not effective in angle recession glaucoma due to distortion of the angle anatomy and TM scarring. If there is a lack of effect in one eye, then it is relatively contraindicated in the fellow eye.

The technique

Approximately 30 to 60 minutes prior to either ALT or SLT, the eye should receive alpha adrenergic agonist, either apraclonidine or brimonidine, to decrease the risk of an immediate IOP spike. Topical anaesthetic is used immediately prior to the procedure to anaesthetise the eye for the laser contact lens.

In ALT, the argon green laser is typically set at a 50-micron spot size, 0.1-second duration, while the power setting can vary between 300 to 1000mW, depending on response. The desired endpoint is blanching of the trabecular meshwork or production of a tiny bubble (figure 4b). If a large bubble appears, the energy should be titrated downward. The laser beam is focused through a goniolens at the junction of the anterior non-pigmented and the posterior pigmented edge of trabecular meshwork. Very posterior application of the laser beam tends to produce more inflammation, pigment dispersion, prolonged elevation of IOP and peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS). Many patients have satisfactory IOP reductions with treatment of 180º of the trabecular meshwork (approximately 40 to 50 applications). Treating 360º is associated with a higher incidence of pressure spikes, but additional 180º of treatment can be performed later if treatment response is appreciated with initial treatment. The ALT procedure can also be performed with a diode laser. In this case, typical settings are 75-micron spot size, 0.1-second duration, and 600 to 1000mW power.

In SLT, the laser is a frequency-doubled (532-nm) Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Selecta 7000, Coherent Medical Group, Santa Clara, CA). The laser settings are fixed except for the power. Spot size is 400-microns and pulse duration is 0.3ns. The large spot size results in low fluences (mJ/cm2). In more lightly pigmented angles, initial energy can be set at 0.8-1.0mJ. In more heavily pigmented angles, the initial power can start off lower at 0.3-0.6mJ. The aiming beam is centered over the trabecular meshwork and straddles the entire TM. Because precise placement of the laser beam is not necessary as it is in ALT, SLT is considered technically easier to do. The aiming beam will not be in sharp focus when the surgeon focuses on the trabecular meshwork to deliver treatment. The treatment endpoint is the appearance of small cavitation bubbles adjacent to the TM. Generally, 180º or 360º are treated in a session. Laser spots can be placed contiguously or several spot sizes apart.

Similar to other laser procedures, it is routine to place a drop of apraclonidine or brimonidine in the eye after ALT or SLT to decrease the risk of a IOP spike.

Approximately one hour after both ALT and SLT, an intraocular pressure check is recommended. If the IOP is elevated beyond what is reasonable for the eye at one hour, the IOP must be treated and the patient should be seen the next day. The treatment required may be mild (ie one hypotensive eyedrop) or aggressive (ie systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors) depending on the eye’s circumstances. The follow-up interval will also depend on the severity of IOP spike. If the one-hour postoperative IOP check is not elevated, the patient can be seen back in one to two weeks. The follow-up thereafter will depend on the patient and doctor, but a commonly followed routine is four to six weeks later and then every three to four months.

After ALT, a topical steroid is prescribed four to six times per day for four to seven days, as the procedure is inflammatory. In SLT, it is more common not to prescribe any anti-inflammatory medications postoperatively, as it is felt that these agents may blunt the biological effects of the laser. Many surgeons will give a script for a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory to be used as needed if patient suffers ocular discomfort. Patients are instructed to resume their usual antihypotensive drops immediately after the laser. A decision to discontinue drops can be made based on IOP response after six to eight weeks. Jha et al provide a useful overview of SLT.6

LiGHT (Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension)

The newly published report1 from the Laser In Glaucoma and Ocular HyperTension (LiGHT) study group is of interest for two reasons. Firstly, the study offers the latest data comparing the effectiveness of SLT as compared with topical drops for the management of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. There have been many studies in recent years showing the SLT technique iin a favourable light.6-9

However, as the new study points out, a Cochrane systematic review published in 2007, highlighted the need for research comparing the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of selective laser trabeculoplasty with eye drops, for lowering intraocular pressure for the treatment of open angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Since then, two studies have shown that 360-degree selective laser trabeculoplasty gives a similar reduction in intraocular pressure to either prostaglandin analogue monotherapy or combination therapy. The studies reviewed, the LiGHT group note, had adopted various follow-up periods and a wide range of success criteria.

The new multicentre randomised controlled trial compared initial treatment of OAG or ocular hypertension using selective laser trabeculoplasty followed by medication, if required, against the standard medication for lowering intraocular pressure alone. In the eye drops group, 36 patients (5.8%) had disease progression compared with 23 (3.8%) of patients in the selective laser trabeculoplasty group, 74% of whom remained drop-free at three years. The laser-first approach provided better control of intraocular pressure over the course of 36 months, with more visits at target intraocular pressure compared with eye drops, less intense drop treatment, and with no glaucoma surgeries.

The second important finding of the LiGHT group, and perhaps more significant in terms of future impact, is that SLT is a cost-effective treatment. This has been implied in previous, usually US-based, studies previously. For example, Centaur et al10 compared the five-year costs of three treatment strategies: medication, laser trabeculoplasty, and filtering surgeries in managing patients with primary open-angle glaucoma whose intraocular pressures were not adequately controlled by two medications. The five-year cumulative costs were approximately $6,571, $4,838 and $6,363 for patients in the medication, laser trabeculoplasty and filtering surgery arms respectively.

The LiGHT study has found that the use ‘of selective laser trabeculoplasty as the first-line treatment resulted in a significant reduction in the cost of surgery and medication for ocular

hypertension and OAG, with an overall cost saving to the NHS of £451 per patient in specialist ophthalmology costs; for every patient given selective laser trabeculoplasty first instead of eye drops the cost savings are greater than the cost of selective laser trabeculoplasty for two additional patients, or equal to the cost of five additional ophthalmology specialist appointments.’

Conclusion

The LiGHT group concludes: ‘Our data support a change in practice; however, clinicians will need to consider patients’ perceptions of the necessity of monitoring visits, in the absence of daily medication. Primary selective laser trabeculoplasty is a cost-effective alternative to drops (figure 5) that can be offered to patients with OAG or ocular hypertension needing treatment to lower intraocular pressure.’

Figure 5: Is this the beginning of the end for drops for glaucoma?

Though there is clearly much debate ahead, and it is known that SLT is not always suitable for a patient, it is important that all eye care professionals are aware of this important study and its conclusions as it is likely to influence discussions within the consulting room in the years ahead.

Ask the expert 1

Consultant ophthalmologist Mr Dan Nguyen answers some questions about SLT

Can you briefly outline what SLT is and when it was first introduced?

- SLT reduces IOP by increasing aqueous outflow through the trabecular meshwork. It was introduced in 1995 and received FDA approval in 2001. SLT’s IOP lowering effect is comparable to a glaucoma eye drop.

Could you perhaps briefly outline what distinguishes SLT from other surgical glaucoma procedures?

- SLT is a clinic-based procedure which involves positioning a patient much like one would at a slit lamp. It is non-invasive in that it doesn’t involve any incisions hence no risk of intraocular infection, and hence a much better safety profile compared to a surgical glaucoma procedure.

What are its key advantages?

- Painless outpatient laser procedure.

- Minimal recovery time.

- Good safety profile and repeatable procedure.

- Good option for patients using drops who have problems with compliance, memory, side effects (ocular or systemic) or allergies, SLT is a useful option to use in order to reduce the number of medications needed for IOP control.

- Can delay or prevent the need for an eye drop, or additional of further drop therapy thereby avoiding the potential associated side effects of eye drops.

- When successful it reduces the risk of non-adherence/non-compliance

Are there any disadvantages?

- The effect of SLT is not permanent.

- The cost of laser, although most hospital eye units should be able to offer it as a treatment.

- There will be a cohort of patients that SLT doesn’t lower the IOP in.

- Although it has a good safety profile, it still remains a laser to the eye hence will have risks which the patient needs to be informed of.

- Cases of corneal oedema, mild uveitis and cystoid macular oedema have been reported, but the risks are infrequent and manageable.

- Involves placing a mirrored contact lens (similar to a gonio lens) on the cornea so important that a patient can tolerate gonioscopy.

- Patient needs to be able to position themselves on a slit lamp.

Is it suitable for anyone with an open angle?

- Yes, can be considered in anyone with an open angle and a clearly visible trabecular meshwork. SLT tends to be more effective in lowering IOP in patients with pigmentation in angle as it targets melanin-rich cells. Patients with heavily pigmented angles (pigment dispersion syndrome) will be at greater risk of a post-laser pressure spike hence one would use a lower power setting for SLT.

Is it something you might consider as a first treatment for a patient?

- Yes, I do consider it as a potential first line treatment for a patient, and believe patients should be offered a choice of SLT or a topical eye drop to lower their eye pressure.

For those on topical hypotensives, is SLT currently only indicated when drops don’t work? Why else might it be used if not?

- Currently the majority of ophthalmologists use SLT to improve IOP control for patients on medication(s) to prevent them needing further medication or surgery.

- SLT can also be used to reduce medication dependence, or the number of medications needed for IOP control.

- It is also a useful option as an alternative to using drops who have problems with compliance, memory, side effects (ocular or systemic) or allergies.

- For patients who pay for their eye drops, SLT can cost-effective.

Does one SLT treatment always suffice for future pressure maintenance or are repeats ever needed?

- An SLT treatment can involve treating 180º, and treating the other 180º on a different session. The entire 360º of the angle can be treated in a single session and this is down to the ophthalmologist’s preference. Treating 360º will be more effective in lowering the IOP.

- The efficacy of SLT does wane over time and a repeat procedure may be required to maintain IOP control.

Once a patient has had SLT, is there any need for continued monitoring or might they be discharged into community eye care?

- It is important that it is made clear to the patient that the laser is not a ‘cure’ for their glaucoma or ocular hypertension, and that they will still need to be monitored.

- Patients will still require monitoring for the reasons mentioned above. Whether this could be done in a community eye setting would depend upon the individual glaucoma service and what provision there is for on-going care and who/how this is delivered.

What are your thoughts regarding the findings of the recent Lancet paper1 – do you see this being the end of ongoing pharmaceutical control except in exceptional circumstances?

- The LiGHT (Laser in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension) compared SLT with the use of drops as a first-line treatment for OHT and glaucoma. It showed that at, six months, almost 75% of patients in the SLT group required no drops to maintain their target IOP. Furthermore, it demonstrated SLT is a cost-effective alternative to eye drops that could be offered to patients.

- Pharmaceutical therapy will still continue to be an effective option to lower IOP.

- I believe there’s enough evidence from this and other previous studies to support primary SLT and it’s an option we can justifiably offer to our patients.

Will the conclusion of the paper be questioned by some specialists?

- The conclusion that SLT ‘should be offered as a first-line treatment for open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension, supporting a change in clinical practice’ seems pretty definitive. The great thing about research is that it is designed to generate debate. It may not change some specialist’s behaviour or management preferences; however, the paper does highlight the potential benefits SLT has for patients and will hopefully encourage specialists to offer this treatment to their patients earlier. Any intervention that achieves IOP control early in the disease process translates to better outcomes.

What would you advise an optometrist who might be asked about the treatment by a patient who may have read reports implying it replaces the need for long-term drop use?

- It could well be an option for them. Any treatment should be individually tailored to the patient and the patient could raise whether this treatment is a potential option for them with their specialist team.

Mr Dan Nguyen is a consultant ophthalmologist and the lead clinician for glaucoma at Mid-Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. He is a consultant ophthalmologist at Optegra Eye Hospital Manchester where he also collaborates with Optegra’s Eye Sciences associates.

Ask the expert 2

Hospital optometrist Paddy Gunn answers questions about SLT, a technique he uses to manage glaucoma

To best understand your role in delivering SLT, could you give a brief description of your current role, background in glaucoma management, and the team with whom you work in Manchester?

- I currently work as principal optometrist at the Manchester Royal Eye Hospital and my role is to lead education and training delivered by the Department of Optometry. My area of clinical interest is glaucoma and I have now been working in glaucoma clinics for almost 12 years. I’m very lucky to be part of a fantastic glaucoma team encompassing optometrists, consultant ophthalmologists, specialist nurses, ophthalmic science practitioners as well as the wider team of community Glaucoma Enhanced Referral Service (GERS) optometrists.

When did you start using SLT?

- I began my training in glaucoma treatment with lasers last summer to allow me to perform both SLT and YAG peripheral iridotomy and have had my own clinic since January 2019

You are a member of a renowned glaucoma team in Manchester, well known for developing advances in screening and referral. Were you the first optometrist to deliver SLT treatment?

- Yes, I was the lucky first optometrist to begin delivering glaucoma laser treatment. This has been something we have been considering for a number of years and so it’s great to expand the ways optometrists can support the glaucoma team.

Can you describe your training? Did you shadow someone else or is there a recognised training process?

- This was a very practical hands-on training, supported by my mentor, consultant ophthalmologist Mr Yau, who I worked alongside in the laser clinic for around six months, performing laser treatments under his supervision. We now have access to model eyes for future optometrists’ training, so they can undertake their first laser treatment in simulation. The model eyes are great, they even produce the champagne bubbles you see during SLT.

Which patients are offered SLT? For those on topical hypotensives, is SLT currently only indicated when drops don’t work?

- SLT has been delivered at the MREH for a decade-and-a-half and has been offered to patients who need additional eye pressure control, who may not want or be able to tolerate further medications, or to try to reduce the burden of taking multiple eye drops.

Can you take us through the process of the procedure, from patient entering the room to them leaving again?

- Patients will arrive at the clinic and have their VA measured by the nursing team, as well as having drops administered to help lower their eye pressure and constrict the pupils.

- A detailed consent process is essential to ensure patients are fully informed of the process, the intended benefits of laser as well as any risks. Once patients have consented to the procedure, they will be taken to the laser room.

- The laser procedure takes just a few minutes per eye.

- After the laser has been delivered, further eye pressure lowering drops are administered.

- The patient’s eye pressure will then be checked an hour later so any spikes in the pressure can be dealt with before the patients are allowed home.

What are your thoughts regarding the findings of the Lancet paper1 – do you see this being the end of ongoing pharmaceutical control except in exceptional circumstances?

- I think the LiGHT trial is a brilliant piece of work by Gus Gazzard and the team at Moorfields Eye Hospital and it will no doubt change the way we offer treatment to patients who are newly diagnosed with ocular hypertension and early glaucoma. I don’t think it will be the end of ongoing pharmaceutical control, but I do think this is really important evidence that will allow glaucoma specialists to be able to offer an alternative non-pharmaceutical option to patients for first line treatment for newly diagnosed patients.

Is the conclusion of the paper likely to be questioned by some specialists? The conclusion that SLT ‘should be offered as a first-line treatment for open angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension, supporting a change in clinical practice’ seems pretty definitive.

- I can only speak for myself and colleagues at the MREH, where we have always been very enthusiastic about the use of SLT as an option to treat ocular hypertension and glaucoma and we’d feel comfortable offering SLT or topical medications as a first line treatment. I think the difficulties some glaucoma specialists will have with the LiGHT study will be surrounding the practicalities of delivering a broader glaucoma laser service.

What would you advise an optometrist who might be asked about the treatment by a patient who may have read reports implying it replaces the need for long-term drop use?

- While patients should feel excited about results of this trial, it’s important optometrists can offer balanced advice about the merits of SLT. The LiGHT study shows that SLT can give drop free eye pressure control to just under 75% of patients newly diagnosed patients with ocular hypertension or glaucoma and so unfortunately it won’t work for all patients. Those already on treatment, or with more severe disease would be less likely to be drop free after SLT.

References

- Gus Gazzard et al; on behalf of the LiGHT Trial Study Group. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Published online March 9, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32213-X

- Keys S. Adverse effects of glaucoma medications. Optician, 01.03.2019.

- Damji Karim F., et al. ‘Selective laser trabeculoplasty v argon laser trabeculoplasty: a prospective randomised clinical trial.’ British Journal of Ophthalmology 83 (1999): 718-722

- Fudemberg, S.J., Myers, J.S., Katz, L.J. Trabecular meshwork tissue examination with scanning electron microscopy: a comparison of micropulse diode laser (MLT), selective laser (SLT), and argon laser (ALT) trabeculoplasty in human cadaver tissue. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49.

- Nguyen D, Khan A, Hickley N. Glaucoma – part 4: surgical management. Optician, 10.07.2015.

- Bhaskar Jha, Shibal Bhartiya, Reetika Sharma, Tarun Arora, Tanuj Dada Selective Laser. Trabeculoplasty: An Overview. Journal of Current Glaucoma Practice, May-August 2012;6(2):79-90.

- Wong M et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of selective laser trabeculoplasty in open-angle glaucoma. Survey of Ophthalmology 60 (2015) 36-50.

- Samples JR et al. Laser Trabeculoplasty for Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2011;118:2296–2302

- Hutnick C et al. Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty versus Argon Laser Trabeculoplasty in Glaucoma Patients Treated Previously with 360 degree Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty - A Randomized, Single-Blind, Equivalence Clinical Trial. Ophthalmology 2019;126:223-232

- Cantor LB, Katz LZ, Cheng JW, Chen E, Tong KB, Peabody JW. Economic evaluation of medication, laser trabeculoplasty and filtering surgeries in treating patients with glaucoma in the US. Curr Med Res Opin 2008 Oct; 24(10):2905-2918.