Spectacles, in their many forms, provide excellent optical correction. Nevertheless, as they are likely to modify perceptions of the individual by others and self, in a world where emphasis is increasingly being put on appearance and attractiveness, it would be of interest to know if spectacle wearers are, or are perceived to be, at a disadvantage.

Spectacles and Physical Appearance

It could be argued that the most immediate judgement that can be made on individuals is that of their physical attractiveness. In a study conducted by Mackinson et al,1 subjects were found to sit more closely to others with certain physical characteristics that had to be considered more attractive. A study by Terry and Kroger2 looked specifically at the effect of eye correctives on ratings of attractiveness. In this experiment two photographs were taken of four females and four males. Each of the subjects had one photograph wearing spectacles and one without. Thirty male and 30 female students rated the photographs. The results showed that each individual was rated lower in attractiveness when they were wearing their spectacles than when he/she was not. In addition, eyeglasses wear produced a lower attractiveness rating in female wearers, comparing to male wearers. Similar finding was reported in another study.3 However, a study by Harris4 revealed rather different findings. In this study, 217 adult subjects were required to evaluate photographs of five males and five females, some wearing spectacles and some not. In addition, participants had to evaluate a ‘typical’ man and woman with spectacles. While photographs with spectacles were rated less attractive, males judged the ‘typical’ woman with spectacles to be more attractive than the ‘typical’ woman without spectacles.

The above two studies were performed in adults. Studies performed in children also show contradictory results. While Terry and Stockton5 found that children generally gave a lower attractiveness rating to their spectacle-wearing peers (particularly girls), Walline et al6 found no effect of spectacles on ratings of attractiveness among children.

Spectacles and Perception of Traits

Thornton7 was one of the first to conduct an experiment into the effects of spectacles on judgements of personality traits. In this study subjects were shown photographs of individuals with and without spectacles. They then rated the individuals in the photographs for different personality traits. The results showed that each individual was rated higher on traits such as dependability, industriousness, intelligence and honesty when they were wearing spectacles compared to when they were not. In 1989 Terry3 conducted an experiment which aimed to establish the stereotypes associated with spectacle wearers and whether the gender of the wearer makes a difference. The individuals included in this study (one male and one female undergraduate) were filmed posing as job applicants. They were filmed individually and both were required to do one video wearing spectacles and one without. Forty-three female and 34 male undergraduates watched the videos and rated the words that best described the subjects from a list of gender stereotypical adjectives. The results showed that both the male and female subjects were rated as having more typically ‘feminine’ traits when they were wearing spectacles. For example, males were considered to be more introverted, timid, mild, gentle and less brave when they were wearing spectacles compared to when they were not. The author suggests that in the modern society, feminine attributes are considered to be less powerful. Nevertheless, the subjects included in the above study were young, white European and therefore represented a very specific section of society.

In a more recent study, Borgen8 used two female and two male models. Three photographs were taken of each individual: once without spectacles, once wearing spectacle with lenses, and once wearing the spectacle without lenses. The same pair of spectacles were used with each individual. By removing the lenses, a message was sent to tell that the eyeglasses are fake, as there was no glare in the photographs. Each individual was asked to pose for three photographs, keeping the same neutral facial expressions and posture. Ten Likert scale phrases were generated, with five as distractors and five concerning intelligence. Each quality was rated on a scale of one to five, with one being the least likely and five being the most likely. Sixty-three college-aged men and women were then asked to complete a study concerning first impressions of others, and they were randomly assigned to one of the three spectacles conditions by using an online randomised program. Their results contradicted other previous findings: they did not find any overall differences in intelligence ratings for each of the presented conditions. The authors concluded that individual qualities are more important than the eyewear in influencing perceptions of intelligence in any individual, regardless of gender.

Terry9 found that spectacle wearers were much more likely to rate themselves as more ‘amicable, efficient, refined, broadminded, kind, reserved, and trustworthy’. These positive traits seem to correlate well with the perception of others towards them as found in Thornton.7 His analyses also indicated that spectacles wearers were less likely to associate themselves with certain less desirable personality traits such as being ‘egocentric, domineering or stubborn’. Although these findings appear to indicate that wearing spectacles has a positive influence on the wearers’ perception of their own personality, the same survey also found that subjects were less likely to perceive themselves as affectionate or brave. Since braveness may be classed as a stereotypically masculine trait, this result may support Terry’s3 finding that ‘eyeglasses made the wearer appear more stereotypically feminine’ to others. Terry’s study may also explain why wearers associated themselves with other stereotypically feminine traits, such as kindness and being trustworthy.

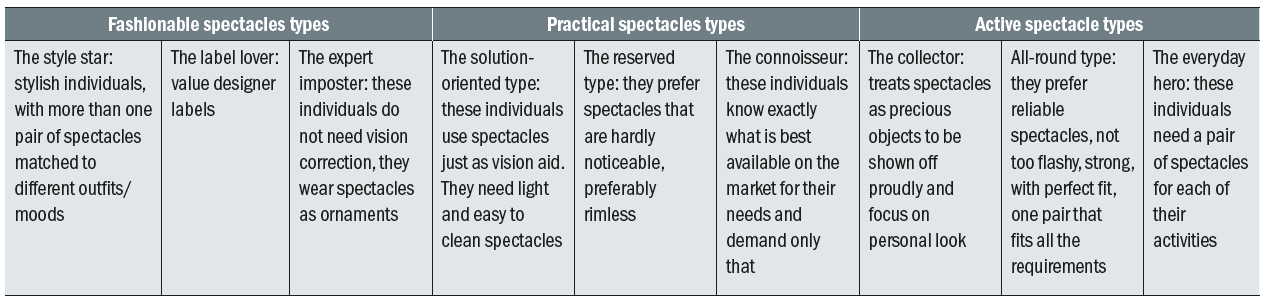

The choice of certain spectacles frames could also offer information about one’s character. A recent publication on Zeiss’ website divided spectacle wearers in three distinct groups (table 1, adapted from the Zeiss website10)

Table 1: A suggested classification of spectacle wearers10

This classification offers a very interesting insight into various personality types of spectacle wearers.

Studies in children

Since self-image concepts begin to form at an early age, it is also important to consider how spectacle-wearing children are perceived by their peers. Walline6 and Terry5 both conducted research into this area but their findings differed greatly. In Walline’s experiment 80 subjects aged between six and 10 years viewed 24 pairs of photos of children (some of whom wore spectacles) and were asked six questions. The questions involved the subject making a choice between the two children in the pair of photographs (eg who would you rather play with?). Walline found that the subjects did not perceive the children with spectacles as significantly different to those without in terms of athleticism, niceness, or shyness. Spectacle wearers were also considered to be as good playmates as non-wearers. In fact, the only difference found was that the children considered those with spectacles to appear smarter and more honest. These results would indicate that children are not as affected by the negative perceptions associated with spectacles the same way as adults are. Terry,5 however, found that first graders rated photographs of children with spectacles as having a poorer school performance and conduct. It was also found that subjects with a higher cognitive ability tended to not like the spectacle wearers as much. Terry suggested this could be an indication that a higher cognitive status is required to recognise the effect and implications of eyeglasses. However, this experiment could also be biased by the fact that older children had a better understanding of the meaning of the experiment conducted. In addition, the conflicted results of the aforementioned studies could also be attributed to the differences in methodology. For example, in Terry’s study the children judged each photograph individually, whereas in Walline’s they were required to make a comparison. Walline’s study also included a larger and more ethnically diverse sample providing a more accurate representation of the attitudes of children today.

Spectacles and Self-Esteem

Although eyeglasses may affect the wearer’s perception of their own attractiveness and personality, it is important to ascertain whether or not this has an overall effect on their self-esteem. An interesting study by Terry et al11 found that spectacles are linked to negative self-esteem; these results were dependent on life period when they were first prescribed but not on how long they have been worn for. It was found that subjects who were first prescribed their spectacles during childhood or adulthood had lower self-esteem than those who had first received them during adolescence. The authors suggested that the lower self-esteem among those first prescribed spectacles during childhood could be due to the fact that during the younger years the self-perception is still being formed and, therefore, more susceptible to change. However, by adolescence, self-perception is more stable and, therefore, less likely to be easily influenced by external factors.

Research conducted by Dias et al12 aimed to evaluate the self-esteem of 469 myopic children over a three-year period and determine whether or not this was affected by the type of their spectacles. It was found that the self-esteem of the subjects remained high over the course of the study, was similar to that of the ‘norm’, and was unaffected by the spectacles that they wore. Walline et al13 used the self-perception profile of children (SPPC) questionnaire designed by Harter in 1985 to analyse the personal perception of wearing spectacles in comparison to contact lenses. He used a sample of children aged between eight and 11 years old. He noticed that social acceptance and physical appearance improved when the participants were not wearing their spectacles, therefore, reinforcing the fact that in young children spectacles wear can have a negative effect on self-esteem.

Spectacles and Bullying

Peers’ opinions mean very much to children, especially when they become older. It has been shown that from the age of five and six, when the children become more socially aware, the positive comments about spectacles wear decline and the negative ones increase.14

A study performed in 2005 by Horwood et al15 found that children wearing spectacles or an eye patch were more likely to be victims of physical or verbal bullying. The study was longitudinal and involved 6,536 children from the UK. Horwood proposed that since the victims were more likely to suffer from overt bullying (physical and verbal) rather than relational bullying (eg being excluded from games), spectacle wearers were seen as physically weaker, thus triggering an overtly aggressive response in peers of an inclined disposition.

It is essential to detect this behaviour and act as soon as possible. It has been shown that, when facing negative comments, children will become non-compliant to wearing their spectacles, a dangerous situation occurring at a critical period in the development of children’s vision. In addition, at this age, children tend to blame themselves for being bullied because they also feel weaker than the rest of their peers.

Conclusions

Although these findings are interesting, much of this research is dated and therefore reflects the views of society at that point in history.

It is also important to remember that although there is a link between social attitudes and self-perceptions, the exact relationship between the two cannot be established from the evidence so far. It is not known whether it is the attitudes of society that make an individual feel a certain way, or whether it is the behaviour of the individual that causes society to judge them that way.

An experience of bullying, however, can be psychologically damaging for a child whose self-concepts are still forming. Since there is some evidence that there is an increased likelihood of bullying among children who wear eyeglasses or patches, the eye care practitioner should aim to provide patching treatment during the preschool years. It is not possible, however, to stop spectacle wear before school age. In these cases, the optometrist may consider offering contact lenses (which can reduce the negative spectacle image) if the patient is really unhappy. It appears as though the stereotypes that people may formulate of spectacle wearers are only an initial perception and quickly fade as the individual learns more about the wearer. More research should be conducted into the individual longevity of these perceptions.

Parents play an important role in the attitude of children towards their spectacles. Indeed, if parents will display negative attitudes towards spectacle correction, these attitudes will be adopted by the children as well. Nevertheless, it has also been shown that any views the child inherits via parental influence are superseded by the views of their peers.16 However, positive reinforcement from parents will have a better effect on children than the messages from optometrists.17 Therefore, the role of optometrists in education has to start with the parents. Handing in written information, displayed in a lay language, is also an important way of reinforcing this message.18 McGregor19 and Farmer17 also suggest that schools should also get involved through organising seminars, school projects and visits from optometrists and opticians. In this way, the schools will also be more aware of victimisation due to spectacle wear, occurring on their premises.

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University from where dispensing optician Mehreen Suleman graduated as an optometrist.

References

- Mackinson, S. P., Jordan, C. H., & Wilson, A. E. (2011). Birds of a feather sit together: Physical similarity predicts seating choice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37, 879-892.

- Terry, R.L., Kroger, D.L. (1976) Effects of Eye Correctives on Ratings of Attractiveness. Percept. Mot. Skills. 42, 562.

- Terry, R.L. (1989) Eyeglasses and Gender Stereotypes. Optom. Vis. Sci. 66, 694-697.

- Harris, M. B. (1991) Sex differences in stereotypes of spectacles. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 21,1659–1680

- Terry, R.L., Stockton, L.A. (1993) Eyeglasses and Children’s Schemata. J. Soc. Psychol. 133, 425-438

- Walline, J.J., Sinnot, L., Johnson, E.D., Ticak, A., Jones, S. L, Jones, L. A. (2008) What do kids think about kids in eyeglasses? Ophthal. Physiol. Opt. 28, 218-224

- Thornton, G. R. (1943) The effect upon judgements of personality traits of varying a single factor in a photograph. J. Soc. Psychol. 18, 127-148

- Borgen A (2005). The effect of eyeglasses on intelligence perception. The Red River Psychology Journal; 1.

- Terry, R.L. (1982) The Psychology of Visual Correctives: Social and Psychological Effects of Eyeglasses and Contact Lenses. Optometric Monthly 73, 137-142.

- Zeiss: A person’s spectacles reflect their character. Choosing spectacles comes down to more than formal criteria – it’s also a matter of type. https://www.zeiss.com/vision-care/int/

- better-vision/lifestyle-fashion/a-person-s-spectacles- reflect-their-character.html (accessed on 21st March 2019)

- Terry, R. L., Berg, A. J., Phillips, P. E. (1983) The effect of eyeglasses on self-esteem. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 54, 947–949

- Dias, L., Hyman, L., Manny, R., Fern, K., COMET group (2005) Evaluating the Self-esteem of Myopic Children Over a Three-Year Period: The COMET Experience. Optom. Vis. Sci. 82, 338-347

- Walline J J, Jones L A, Sinnott L, Chitkara M, Coffey B, Jackson J M, Manny R E, Rah M J and Prinstein M J (2009). Randomized trial of the effect of contact lens wear on self- perception in children. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/optvissci/ Abstract/2009/03000/Randomized_Trial_ of_the_Effect_of_Contact_Lens.9.aspx

- Swertz M. Contextual, developmental and cultural effects on effective display in children, [pdf] 2012. Available at: http://prosodia.upf.edu/home/arxiu/ activitats/1202_swerts.pdf

- Horwood, J., Waylen, A., Herrick,D., Williams,C., Wolke, D. (2005) Common Visual Defects and Peer Victimisation in Children. Invest. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46, 1177-81

- Rich-Harris J (1999). The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do. New York: Touchstone publications

- Farmer M. Spectacle wear compliance. Optician, November 2012

- Johnson A, Sandford J and Tyndall J. Written and verbal information versus verbal information only for patients being discharged from acute hospital settings to home (2008). Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003716/abstract

- McGregor-Read S (2000). Why do young children not wear spectacles in school? Available at: http://primaryhealthcare. rcnpublishing.co.uk/archive/article-why- do-young-children-not-wear-spectacles-in- school (accessed 29th March 2019)