Most optometrists are fairly familiar with sight impairment due to ocular pathology. On the contrary, visual impairment due to damage to the brain tends to be a ‘hidden’ cause of low vision, despite the fact that it is now the leading cause of severe sight impairment in children in England and Wales.1 The first article in this series discussed how optometrists can contribute to the identification of CVI by understanding the visual pathways from eye to visual cortex and the ventral and dorsal stream pathways that are responsible for higher visual processing. It highlighted what to look out for in terms of family history, birth history, general health and development and ocular risk factors. Once CVI is suspected, the question is what optometrists can offer to support their patients.

This article will give some advice about how to take a history to characterise the CVIs that are present, question inventories and investigative techniques.

History, symptoms and Question Inventories

In a standard optometric examination, the aim is to detect refractive error, ocular pathology and abnormalities in visual and binocular function. During history taking information is elicited by asking questions about the following:

- The nature of symptoms: For example, flashes, floaters, diplopia, eye strain, headache, pain or redness

- Time; onset, duration and frequency of symptoms

- Location; which part of the eye/body is affected

- Exacerbating, contributing and ameliorating factors

- Treatment to date

- Understanding of the (eye) condition

Similar questions can be asked in a functional assessment, but this time the aim is to elicit information about visual behavioural patterns rather than pathology:

- Features: ‘What happened?’ This may include tripping over things, getting distressed in busy places, poor concentration, clumsiness, dangerous road crossing behaviour.

- Time: ‘How long have you noticed the behaviour for?’, ‘How often does it happen?’, ‘When did it last happen?’

- Location: ‘Where did it happen?’ For example, at school, in the supermarket, at home.

- Exacerbating factors, adaptations and reactions: ‘What is the behaviour like?’, ‘What makes it better/ worse?’ For example, anger, withdrawal, anxiety, worse when tired or in busy environment. Children may have adapted or reacted to their impairment by making use of intact vision, compensating with other senses or avoiding situations.

- Treatment and interventions to date: Previous advice on how to deal with the difficulties? What has been tried already?

- Understanding the visual problems and behavioural traits: What is their current understanding?

As with any history taking, it is best to start with open (non-leading) questions, such as ‘Can you tell me what you have noticed about your child’s vision?’. This gives the parent/carer an opportunity to express their concerns, and is necessary to find out about the visual difficulties without giving the parents any initial clues about how CVI presents and the difficulties it causes. Closed, non-leading questions clarify more details about the visual behaviour of the child, once the initial picture has been identified. For example, ‘What happens when your child goes to an unfamiliar place, such as a friend’s house?’ In closed leading questions, such as ‘Does your child get upset when you leave immediately?’ the answer is implied. This type of questions highlights what kind of behavioural features are being sought.

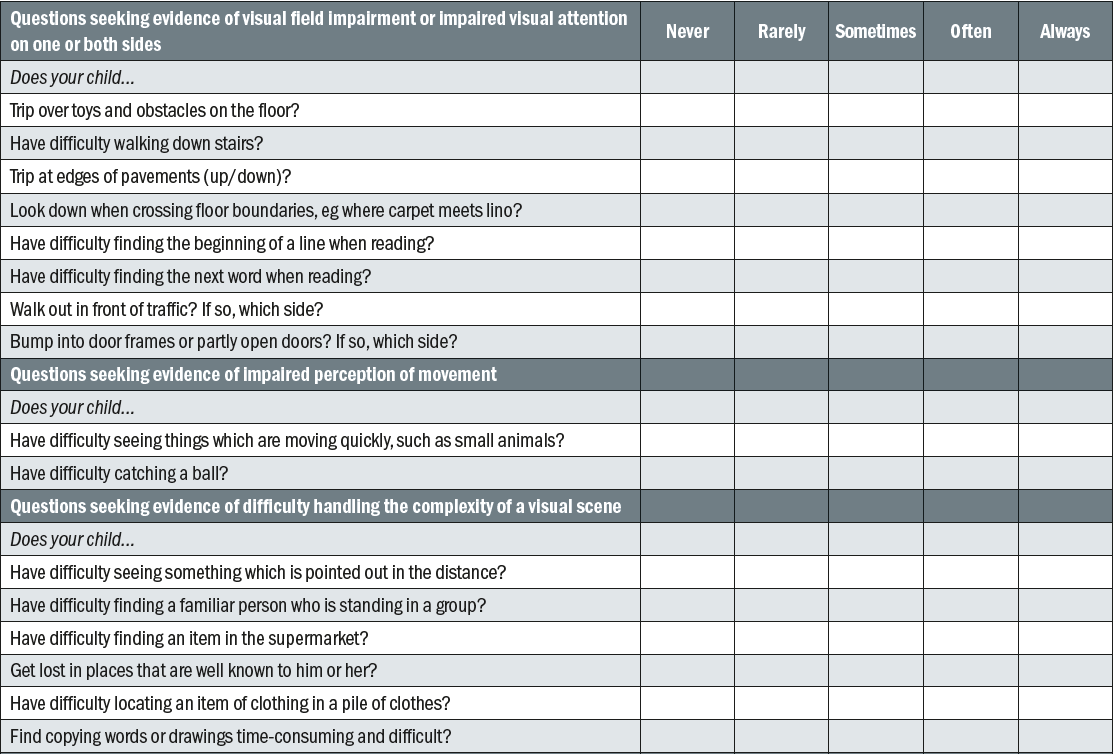

CVI is a condition with many different presentations and symptoms and it is helpful to have some structured questions to cover different areas of dysfunctions. Zihl and Dutton 2 and Dutton and Bax 3 have introduced Question Inventories to build a picture of the patient’s visual world. Questions are grouped according to specific dysfunctions (table 1).3

Table 1: Question Inventory for parents/carers of children with CVI and VA 6/60 or better. Adapted from Dutton and Bax 3

Going through each category of possible dysfunction helps to understand the type of difficulties that may be expected and more issues may be revealed during the interview as this is not an exhaustive list. Explaining the underlying mechanism of specific difficulties is much easier when they are grouped together. To further understand the underlying mechanisms, some measures of visual function are required.

Investigative techniques

In a functional vision assessment, investigative techniques are carried out with a view to plan (re)habilitation strategies and interventions. Although strabismus and amblyopia are common features in CVI,4,5 it will be assumed that the reader is familiar with the assessment and management of these conditions. As it is the nature of the overall vision that is being sought, vision is tested with both eyes open. Extra care needs to be given to refraction and prescribing as CVI is associated with reduced accommodation and convergence. One also has to be careful to use an appropriate technique for the patient’s age and cognitive ability.

Distance visual acuity

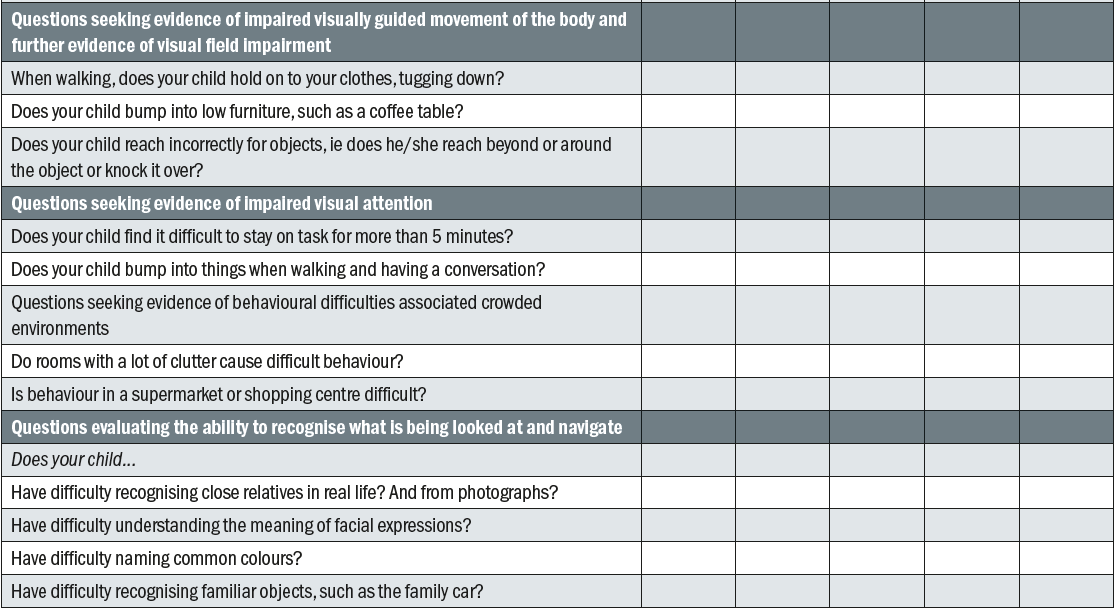

Figure 1: LogMAR acuity chart

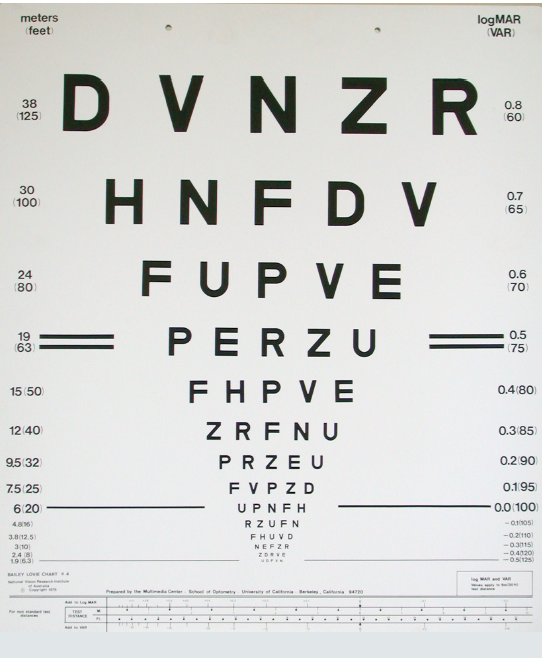

For distance visual acuity, a LogMAR based test (figure 1) is preferable as this is more precise and allows for accurate conversions at different test distances.6 For adults and older children, the Bailey-Lovie or ETDRS charts can be used. Single and crowded pictures or letters are suitable for children. Examples are: Keeler LogMAR Crowded Test, Kay Letter and Kay Picture Test (single or crowded, figure 2) and Lea Symbols (crowded and uncrowded). These tests usually have a matching card for pre-school children or non-verbal children or adults with reduced cognitive ability. For even younger children, preferential looking tests can be used to assess vision. Examples are: Cardiff Acuity Cards, Teller Acuity Cards and Lea Paddles.7 One has to bear in mind that most people find single letters/pictures easier than crowded ones, but that this difference may be much more significant in patients with dorsal stream dysfunction,8 in which the level of acuity can diminish significantly more with crowded letter charts. A binocular visual acuity that is significantly lower with crowded charts than with single letters or images is indicative of this condition.

Figure 2: Kay picture test

Refraction

High refractive error is a common feature in CVI4,5,9,10 A suitable refraction technique is chosen depending on the age and ability of the patient. Static retinoscopy and subjective refraction may be appropriate for some patients. Others may be better assessed using cycloplegic refraction or Mohindra retinoscopy. Mohindra retinoscopy can be followed by dynamic retinoscopy to assess accommodation. Near vision can then be checked with and/or without a near addition. In case different magnifiers are considered, unit magnification can be assessed using a +4.00D near addition. Advice on prescribing Low Vision aids is outside the scope of this article and will be covered in a future CET article in Optician.

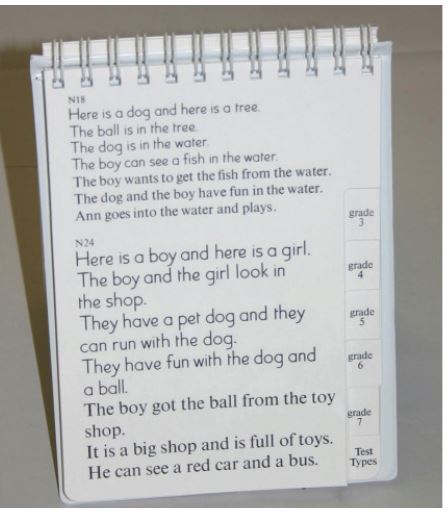

Near Vision

For children, Kay pictures or Lea symbols can be used with a matching card to assess the ability to detect a particular print size. The Maclure Reading Test Type for Children 18 is used for school-age children who are able to read and is designed to assess reading speed and fluency (figure 3). For adults, the Bailey-Lovie Word Reading Chart measures threshold print size, but one has to be careful to recommend a print size that is well above threshold for sustained reading tasks.11 The MN read17 is an example of a reading chart for assessing reading speed and fluency for adults. Standard reading charts are designed to assess the print size being read. However, the use of of samples, such as newspapers, music scores, magazines, TV guides, bingo cards, knitting patterns, school books and picture books give a more realistic picture of everyday functioning. Patients can be asked to bring in samples of material they would like to be able to read or access. For some patients the goal is to see pictures in a picture book. Knowing the minimal line width required to see, helps to plan interventions.

Figure 3: Maclure Reading Test Type

Accommodation

CVI is commonly associated with impaired accommodation.4 Depending on the level of ability, near vision and amplitude of accommodation can be assessed with a near target. Dynamic retinoscopy is a recognised method to assess accommodative lag. Reading glasses and/or bifocals can be prescribed accordingly.

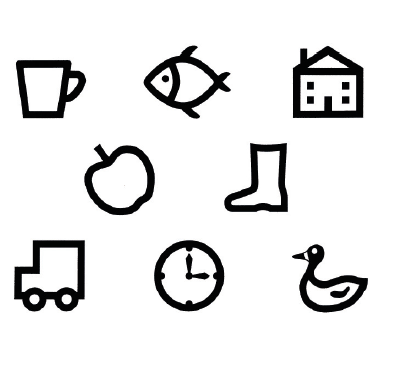

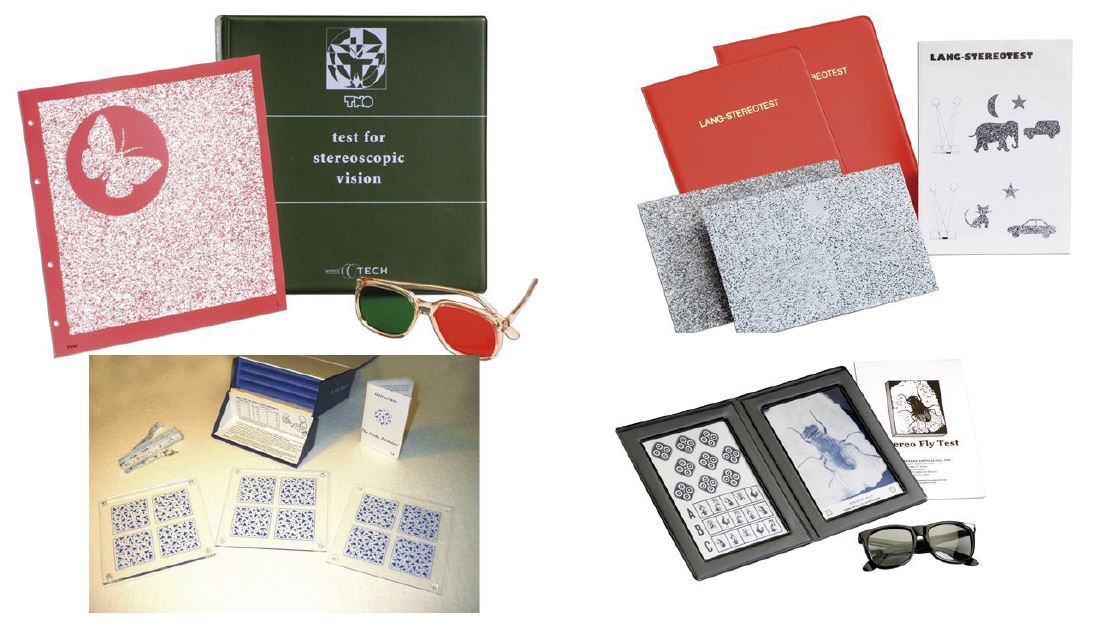

Contrast sensitivity, stereopsis, colour vision

Contrast sensitivity, stereopsis and colour vision12,13 can be reduced in CVI. Preferential looking cards, such as Cardiff Contrast cards, are easy to use and suitable for any age. For stereopsis, there is a wide range of available tests for different levels of ability ranging from Lang and Frisby to the more complex TNO stereo test (figure 4). For colour vision, the Mollon-Reffin test is easier to use from a young age and preferable to Ishihara plates.14, 15

Figure 4: Stereopsis tests

Nystagmus

Nystagmus is a common finding in CVI.4 A functional assessment of nystagmus is concerned with the observation of the presence of a null point and/or intensifying of the nystagmus in any directions of gaze. This information is used to decide on optimal position in the classroom, in social situations and for mobility. The child needs to be advised on optimal use of null point. For example, if the nystagmus intensifies in up-gaze, the child may well struggle when the teacher gives instructions to the children during ‘carpet time’ (children sitting on the floor with teacher on chair giving instructions and using smart-board). This child may benefit from sitting on a chair to avoid up-gaze.

Visual fields

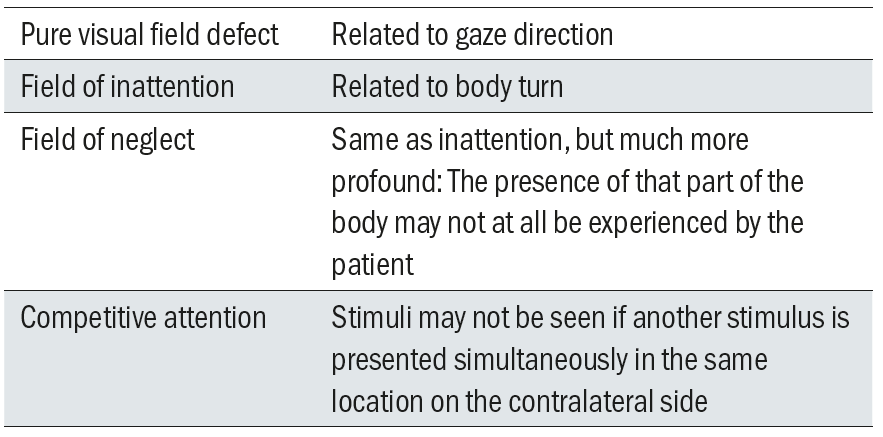

Visual field (VF) assessment in patients with CVI is most meaningful when the optometrist considers the functional impact of the visual impairment. Functional fields are assessed with both eyes open. It is important to understand the difference between a pure VF defect, which originates from a lesion in the primary pathway (ie from eye to primary cortex) and a field of inattention or visual neglect (ie higher visual processing dysfunction) due to a lesion in the parietal lobe. Most optometrists are familiar with VF defects in the primary visual pathway. These VF defects are easily mapped with perimetry and correlate to the location of the lesion on different points of the pathway. One example of this is homonymous hemianopia due to a lesion in the optic tract. However, fields of inattention are different from hemianopia in that they are not always apparent on ordinary perimetry. Fields of inattention and neglect are less well understood by most and are not routinely assessed in the optometric practice. The impact of inattention and neglect on functional vision is considerable. Therefore, this needs to be assessed if one is keen to offer their patients (re)habilitation strategies. Lower fields also need to be assessed as dorsal stream dysfunction can be associated with peripheral lower field inattention.16 Table 2 summarises some key terms in visual fields assessment of CVI patients.

Table 2: Glossary of visual fields terminology

There are a number of valid methods of visual field testing. The following method is a possible way to investigate field impairments for the purpose of planning compensation strategies.

To detect presence of hemianopia

- Examiner faces patient straight ahead

- Patient looks at examiner’s eyes with knees pointing at examiner’s knees

- Examiner moves finger in each quadrant in diagonal plane

- If finger is not seen, repeat with larger movement of finger or hand movement to check for relative defect

- If a field defect is present, establish the boundaries

To detect presence of hemi-neglect if field impairment was present

- Repeat above, but:

- Examiner faces patient straight ahead

- Patient points knees to the right and looks at examiner’s face (right body-turn)

- Repeat, but this time with left body-turn

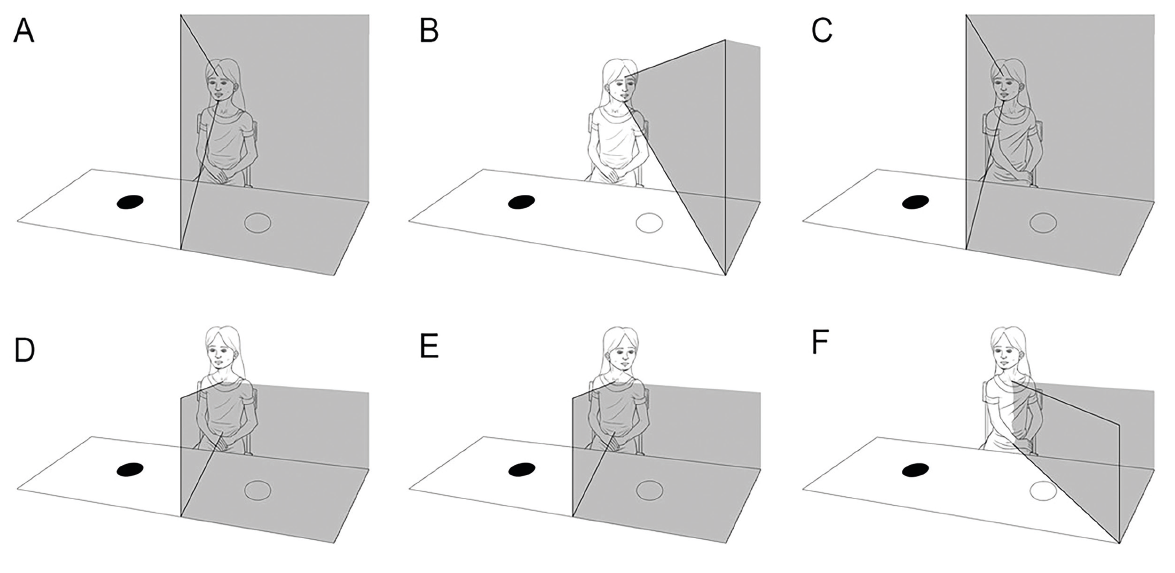

Figure 5 shows field defects with and without inattention.

Figure 5: Visual fields in hemianopia without inattention (ABC) and with inattention (DEF)

To detect presence of competitive attention

- Examiner faces patient straight ahead

- Patient looks at examiner’s eyes with knees pointing at examiner’s knees

- Examiner presents moving fingers simultaneously in opposite (mirror) quadrants

- If patient can only see one finger, this confirms competitive attention

To detect presence of lower visual field impairment

- Patient stands up, holding on to something or someone to prevent falling backward

- Patient is asked to lift their legs in turn whilst looking at examiner’s eyes.

- How far does the patient need to lift their legs before they are seen?

- The extend of the lower field impairment can vary from not seeing the feet when walking to not seeing anything below waist level

Why do we need to know about all these different VFs? Because of the practical implications for (re)habilitation. For hemi-inattention, body turn needs to be explained and understood, so the patient can work out strategies to compensate for the inattention. For example, safe road crossing and visual search can be improved by maximising the field of attention. The optimal body position can be established for socialising and navigation. A lower field inattention tends to lead to collisions with low furniture and problems with going down stairs, steps and curbs. A hiking pole can help improve mobility by feeling the (unseen) ground ahead. A lower field inattention also causes the patient to only see the top part of a textbook. A reading stand can help.

Intervention strategies and (re)habilitation

It is outside the scope of this article to describe all the possible interventions. However, it is helpful to think about the impact of visual dysfunction on social interactions, access to information and visually guided movement.2 Each of these factors need to be addressed when intervention strategies are planned. CVI has impact on psychosocial functioning as well. Feelings of anxiety and inadequacy are common, interaction with others can be negatively impacted and fatigue leads to reduced overall coping and performance. Some rehabilitation strategies are shared below:

- Magnification (if vision is reduced). This includes relative size magnification (making object larger, eg large print books), relative distance magnification (eg sit closer to the TV, use of hand magnifiers), transverse magnification (electronic devices) and angular magnification (telescopes).

- Improve use of contrast and lighting.

- De-cluttering the environment and organising storage.

- Making use of other senses, eg tactile guidance, recognising people by their voice, using audio books and audio technology, Braille.

- Compensation strategies and adaptive approaches, e.g. verbal reminders and description of the unseen environment, scanning techniques, utilising seeing field, using pedestrian crossings, avoiding certain situations that are known to cause upset. Zihl and Dutton 2 include a table with a more detailed list of adaptive strategies for specific difficulties in their book ‘Cerebral Visual Impairment in Children: Visuoperceptive and Visuocognitive Disorders’.

- Educating and empowering the patient and their carers: This is the most important of all.

- Mobility training.

- Peer support.

- Liaising with other professionals and voluntary organisations that can give support.

Conclusion

This article has provided a brief overview of methods to characterise the CVI’s of patients through history taking, Question Inventories and investigative techniques. Once the CVIs are characterised, an intervention plan can be made. Managing patients with CVI is very rewarding, but can be time-consuming. It is impossible for the practitioner to understand how the CVIs of each individual are affecting all aspects of their daily life and it is not realistic to take on such a huge responsibility. The parents, partners, carers and teachers of the patient are much better placed to help the patient to function optimally. For this reason, it is crucially important that they are empowered with understanding about the visual dysfunctions and the mechanisms that play a role and with information about strategies and interventions that have helped other patients. Further information and support for patients, families and professionals can be found on CVI Scotland’s website: www.cviscotland.org.

Cirta Tooth is a hospital optometrist based in Edinburgh with a special interest is low vision and functional vision.

Acknowledgement

Figure 5 was adapted from: Lueck, Amanda H.; Dutton, Gordon N. (Eds.) (2015). Vision and the Brain: Understanding Cerebral Visual Impairment in Children. New York: AFB Press. (With permission from Dutton GN.)

References

- Mitry, Danny; Bunce, Catey; Wormald, Richard; et al. 2013. Childhood visual impairment in England: a rising trend. Archive of Diseases in Childhood 98(5).

- Zihl, J and Dutton, GN. 2015. Cerebral visual impairment in children: visuoperceptive and visuocognitive disorders. 1st ed. Wien. Springer-Verlag. X

- Dutton, GN and Bax, M. 2010. Visual Impairment in Children due to Damage to the Brain. MacKeith Press, London, pp. 106-116.

- Kheptal, V and Donahue, SP. 2007. Cortical visual impairment: etiology, associated findings, and prognosis in a tertiary care setting. Journal of American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 11(3), pp. 235-239.

- Pehere, N et al. 2018. Cerebral visual impairment in children: causes and associated ophthalmological problems. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 66(6), pp. 812-815.

- Lovie-Kitchin, J. 2011. Reading with low vision: the impact of research on clinical management. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 94(2), pp. 121-132.

- Mody, KH et al. 2012. Comparison of Lea gratings with Cardiff acuity cards for vision testing of preverbal children. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 60(6), pp. 541-543.

- Hyvärinen, L. 2010. Classification of visual functioning and disability in children with visual processing disorders. In: Book Dutton, GN and Bax, M. 2010. Visual Impairment in Children due to Damage to the Brain. MacKeith Press, London, p. 270.

- Das, M. et al. 2010. Evidence that children with special needs all require visual assessment. Archives of Disease in Childhood 95(11), pp. 888-892.

- Saunders, KJ. 2010. Profile of refractive errors in cerebral palsy: impact of severety of motor impairment (GMFCS) and CP subtype on refractive outcome. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 51(6), pp. 2885-2890.

- Lovie-Kitchin, J E and Whittaker, SG. 1999. Interaction between acuity reserve and window size for scrolled reading rates in adults with normal and low vision. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 40(4), pp. S34-S34.

- Koh, S. et al. 2008. Stereopsis amd color vision impairment in patients with right extrastriate cerebral lesions. European Neurology 60(4), pp. 174-178.

- Zihl. J. 2000. Cerebral visual disorders. Aktuelle Neurologie 27(1), p. 13

- Ajwani et al. 2014. Comparative analysis of the Mollon-Reffin Minimal Colour Vision Test in visually ‘normal’ and acquired ocular disease. Ophthalmology Research: An International Journal 2(2), pp.65-77.

- Pompe, MT and Kranjc, BS. 2012. Which psychophysical colour vision test to use for screening in 3-9 year olds? Zdravniski Vestnik-Slovenian Medical Journal 81(S), pp. 170-177.

- Dutton, G.N. et al. 2004. Association of binocular lower visual field impairment, impaired simultaneous perception, disordered visually guided motion and inaccurate saccades in children with cerebral visual dysfunction- a retrospective observational study. Eye 18(1), pp. 27-34.

- Legge, G.E. MNRead. Available at: http://legge.psych.umn.edu/mnread [Accessed 27 Mar 19].

- Sussex Vision. Maclure Reading Test. Available at: https://www.sussex-vision.co.uk/maclure-reading-test-type-for-children. [Accessed: 27 Nov 2018].