‘...I feel very much more secure with the growing number of optometrists in this country who are becoming knowledgeable about implications of public health and its relationship to our profession. You only had to go back a short period of time to find that we had only a small hard core group of people who were truly concerned with public health. At that time they were looked upon as wide eyed liberals who were running around trying to create problems for the profession and not providing solutions. Our awareness has increased and I would like to tip my hat… to those people who have made a significant contribution in the area of public health to this profession.’

Opening remarks, Melvin Wolfberg, Workshop Conference on public health and optometric care, St Louis, Mo., October 27-28, 1969

‘Public health’ refers to all the regulated and organised activities that ensure disease prevention, health enhancements programs and an increased quality of life. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), public health is defined as ‘the art and science of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organised efforts of society’. All these objectives can be achieved through education, research, policy making, vaccinations, disease screening and counselling, smoking cessation, to name just a few. Public health also works to limit health disparities within communities.

The role of optometrists in public health started quite late in the 20th century, with preventing sight loss, ocular injuries and diseases and setting standards for eye protection at the workplace. This has progressed later to prevention of vision loss from diseases such as diabetes, age-related maculopathy and glaucoma. Nevertheless, ‘preventive optometry’, a philosophy in use since 1950,1 allows the optometrist to be the main catalyst for more than managing eye disease and preventing visual loss. Some of these possible aspects of the optometric practice are explored below.

Smoking cessation

Smoking represents a risk factors for a large spectrum of disorders, from cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke and various forms of cancer to back pain and dementia. Smoking is also an important contributing factor to the onset of ocular diseases, including:

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

- Dry eye

- Cataract

- Uveitis 2

- Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG)3

- Graves’ disease

Nevertheless, despite the established link between tobacco smoking and various adverse ocular health outcomes, it has been reported than only a fraction of community optometrists regularly ask their patients about their smoking habits .4-6 This is despite the fact that many of our patients would be happy to discuss this issue with their optometrist. Indeed, in a recent unpublished study, we have found that over 50 % of patients attending optometry practices believe optometrists are sufficiently qualified to advise about the effects of smoking on ocular and general health.7 It has been reported that even a very brief counselling, of less than three minutes duration, can increase smoking cessation rates by up to 30%.8

Therefore, optometrists should be equipped with the knowledge and practical skills to support their patients with smoking cessation. The message can also be delivered indirectly by having relevant materials (posters and leaflets) available in the waiting rooms. This awareness should start early. Our optometry schools should include practical training to support smoking cessation in their curricula; at the moment, this area is still lacking.9 In addition to training, optometrists also need to work together with other healthcare providers in providing a unified message to patients; this will increase the chance of success.

High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease prevention

Systemic arterial hypertension represents the main cause of stroke and a major risk factor for heart disease, such as heart attack and heart failure. It can also induce severe kidney disease and ultimately, kidney failure. Approximately one-third of people with systemic hypertension are still undiagnosed and the disease is responsible for more than 62,000 preventable deaths through stroke and heart disease each year (data from Blood Pressure UK).

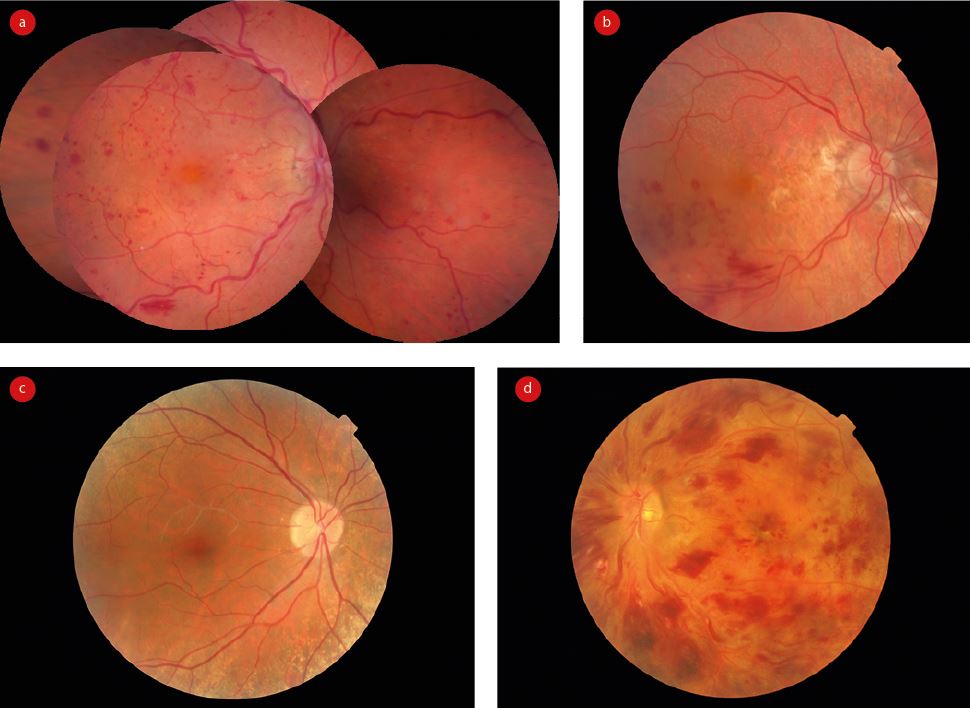

At the ocular level, focal and generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing, arteriovenous nipping, cotton-wool spots, microaneurysms, flame and blot-shaped retinal haemorrhages, exudative maculopathy and disc oedema are vascular signs that reflect high BP of various degrees, all easy to detect by a trained eye. Nevertheless, in addition to detecting and monitoring the above fundoscopic changes, optometrists can also play a role in BP monitoring. It is often the case that most of our patients have a well-controlled systemic hypertension and comply to their treatment. However, in other situations the patients are either non-compliant with their treatment regime or the medication is inefficient.

Therefore, on the spot checking of BP by the optometrist can often detect abnormal values in individuals with fundoscopic changes that suggest systemic hypertension. It has been suggested since 1976 that optometrists measuring blood pressure routinely could detect the disease in as many as 1 in 14 undiagnosed hypertensive adults attending for routine sight tests.10 Nevertheless, despite the fact that measuring systemic BP does not require specialist training, only a small proportion of optometrists use BP monitors in their practice. It has been reported that approximately 33% of UK optometrists will modify their ocular examination if they are aware or suspect a patient’s blood pressure in not within normal limits.11 There is, therefore, a high need to increase awareness among optometrists and possibly offer them specialist training for measurement and interpretation of BP values.

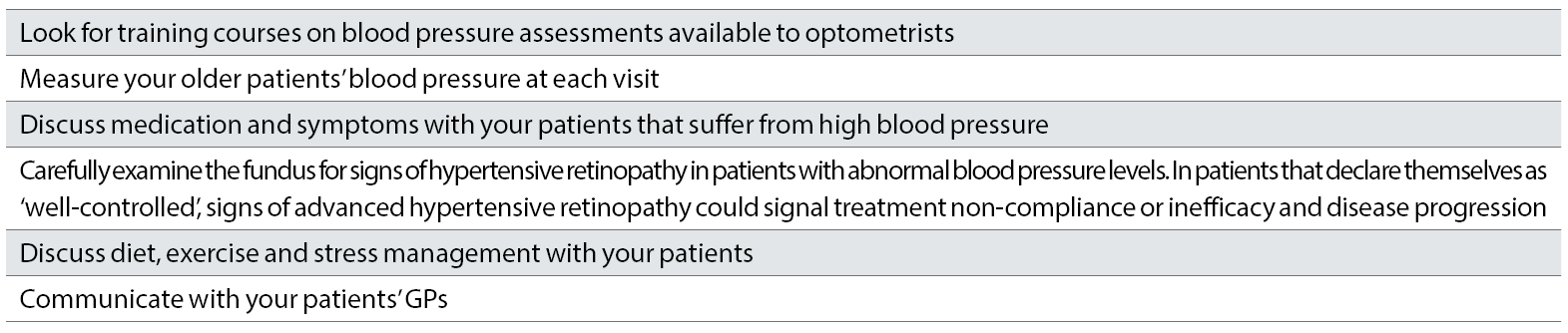

As outlined in table 1, there are few recommendations for optometrists regarding diagnosis and management of systemic hypertension (adapted from 12).

Table 1: Recommendations for optometrists concerning vascular health issues

Obesity and nutrition

Obesity is an escalating global epidemic and a major risk factor for several chronic systemic diseases, including hypercholesterolaemia, high blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), stroke, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), various cancers, osteoarthritis and diabetes mellitus (DM). In addition, obesity is associated with higher risk for various ocular complications including dry eye, floppy eyelid syndrome (FES), cataract, hypertensive and diabetic retinopathy, AMD and glaucoma. Beside ocular diagnosis and management, optometrists can also get involved in obesity management by providing advice on nutrition. In our above-mentioned unpublished study 7 we have also reported that a large percentage of patients attending optometric practice are considering their optometrists qualified to provide them with nutritional advice. From our sample, however, only 13.2% of patients were routinely asked about their nutrition by their optometrist and only 5.3% received nutritional advice from these practitioners. This is a in agreement with previous published research.13 It is possible that the percentage of patients receiving advice on nutrition from optometrists is higher among those diagnosed with AMD.14

Healthy pregnancy

Pregnancy represents a physiological state associated with a large variety of changes throughout the mother’s body, including metabolic, hormonal, circulatory, immunologic, pulmonary and renal, that allow a heathy gestation and delivery. All organs are affected during this process, including the eye. The changes can be either physiologic or pathological and most of the time they revert back to the normal state after delivery or breastfeeding. General water retention in pregnancy also affect corneal thickness, curvature and contributes to a decreased corneal sensitivity. These changes might adversely affect contact lens wear during pregnancy and postpartum lactation. In addition, in 14% of pregnancies, there is an increased lens hydration and thickness that can also contribute to the fluctuations in refraction observed during pregnancy. These fluctuations are also due to a temporary loss of accommodation during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Ocular changes associated with pregnancy are outlined in table 2.15

In addition, the course of diseases present before the pregnancy can also be altered. Diseases such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy and Graves’ disease will suffer changes in prognosis once the patient becomes pregnant. Moreover, treatments that were well tolerated by the body before gestation could have a detrimental effect on the foetus and, therefore, need to either be stopped or replaced by alternatives. In such situations, the patients will be under the care of ophthalmologists and other specialists, therefore, the role of optometrists is limited. Nevertheless, optometrists can be the first to diagnose pregnancy-induced ocular complications, such as pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH), retinal vascular occlusions, central serous retinopathy (CSR) and ischaemic optic neuropathy (ION). In addition, optometrists should also be aware about safety issues of diagnostic drugs use in pregnant women. At present, although some guidelines do exist, we are lacking a complete knowledge about safety of ophthalmic drugs in pregnancy. In addition, there is also controversy about using chloramphenicol drops in pregnant women.16

An important aspect of the optometric care in pregnancy is represented by the management of unstable refractions and contact lens or spectacle prescriptions. Nevertheless, optometrists can also be involved in the careful assessment of the retinal health, monitoring of pre-existing diseases and even measurement of blood pressure in these women, therefore, contributing to prevention and early diagnosis of various morbidities.

Other: alcohol consumption and high cholesterol

Optometrists can also be involved in other aspects of public health, such as alcohol consumption as well as detecting signs of high levels of lipids.

Alcohol is a legal addictive substance that has a large number of adverse ocular effects, such as paralysis and jerky pursuit movements of extraocular muscles, downbeat nystagmus, paralysis of accommodation, decreased visual discrimination, miosis with a reduced or absent reaction to light, visual field defects, decreased intraocular pressure (IOP), optic neuritis, arcus senilis and toxic neuropathy. Dry eye, cataract, refraction changes, transient amblyopia, jaundice (due to liver damage) and high IOP in glaucoma patients has also been described. More information about the role of optometrists is detecting problems associated with alcohol consumption are detailed in a previous article published in Optician in January 2017.17

Patients with high cholesterol levels can present with the following ocular signs:

- Xanthelasma, a yellow deposit of lipids at the eyelid level caused by elevated levels of triglycerides and cholesterol in the blood as well as metabolic disorders, including familial hypercholesterolaemia (figure 1).

- Corneal arcus, or lipid keratopathy, a grey or white ring at the periphery of the cornea, represents a sign of familial hypercholesterolaemia, especially in patients younger than 50 years old18 (figure 1).

- Lipaemia retinalis, a rare occurrence of hypertriglyceridemia that does not occur until the triglyceride level reaches 2500mg per decilitre. It is characterised by hyperlipidaemic vascular lesions with whitish-coloured vessels, lipid infiltration into the retina and decreased visual acuity.19

- Retinal vascular occlusions (figure 2).

In addition, cholesterol-lowering medications such as statins have been reported to induce ocular side effects such as blurred vision, abnormal ocular motility, diplopia and ptosis.20

Conclusions

The role of optometrists varies in different countries, from roles strictly limited to eyesight correction to disease diagnosis, minor surgeries and drug prescriptions. Nevertheless, when it comes to public health, it is still unclear what optometrists should do. In the UK, the scope of optometric practice is expanding and now includes independent diagnosis as well as management and prescribing for various ocular conditions.

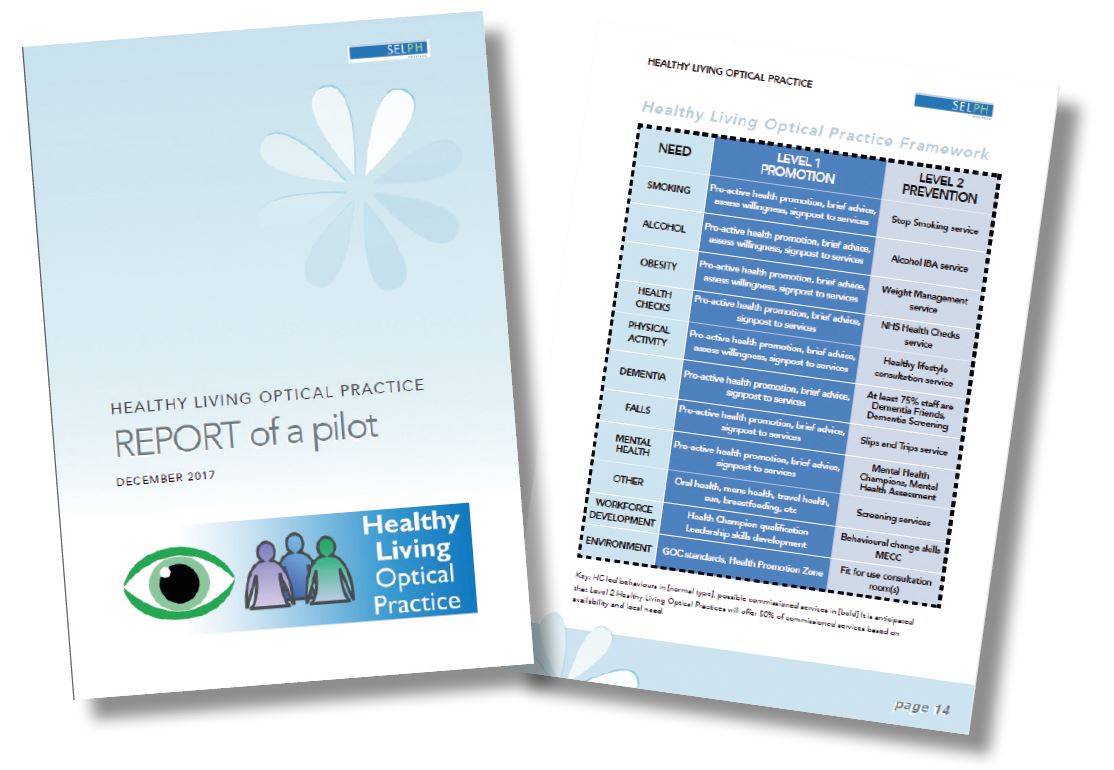

More recently, there are implemented various schemes, such as Dudley ‘Healthy Living Optician’ Scheme (figure 3), where optometrist practices offer advice on smoking, weight control, alcohol consumption and even testing the circulating levels of glucose and cholesterol.

Figure 3: The Dudley ‘Healthy Living Optician’ Scheme (selected pages)

In addition, optometrists are increasingly working together with both pharmacists and GPs to address general public health issues as part of NHS primary care teams.21 However, this type of practice is still sporadic. In addition, patients do not usually expect that their optometrist will ask in-depth questions about their health, offer advice or perform any other assessments than checking their ocular health. Good optometric practice means, however, that optometrists are at the forefront in offering immediate help and advice and, therefore, by being familiar with various systemic diseases with ocular consequences, they will be able to take appropriate management decisions that help prevent morbidity and mortality in the general population attending the average optometric practice.

Dr Doina Gherghel is a lecturer in ophthalmology at the School of Life and Health Sciences, Aston University.

References

- Jacques L. Corrective and preventive optometry (1950). Los Angeles: Globe Print Co.

- Yuen BG, Tham VN, Browne EN et al. (2015). Association between Smoking and Uveitis: Results from the Pacific Ocular Inflammation Study. Ophthalmology. 2015 Jun;122(6):1257-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.02.034

- Edwards R, Thornton J, Ajit R et al (2008). Cigarette smoking and primary open angle glaucoma: a systematic review. J Glaucoma. 2008 Oct-Nov;17(7):558-66. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31815f530c.

- Lawrenson JG & Evans JR. Advice about diet and smoking for people with or at risk of age-related macular degeneration: a cross-sectional survey of eye care professionals in the UK (2013). BMC Public Health; 13: 564

- Thompson C, Harrison RA, Wilkinson SC, et al. (2007). Attitudes of community optometrists to smoking cessation: an untapped opportunity overlooked? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt; 27: 389–393

- Downie LE & Keller PR. The self-reported clinical practice behaviors of Australian optometrists as related to smoking, diet and nutritional supplementation (2015). PLoS One 2015; 10: e0124533

- Maryuma D, Gherghel D. Optometric Involvement in Smoking, Nutrition, and Blood Pressure Management –What are the Patients’ Perceptions?- unpublished data

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Care Guideline. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update

- Lorencatto F, Harper AM, Francis JJ et al. A survey of UK optometry trainees’ smoking cessation training (2016). Ophthalmic Physiol Opt; 36: 494–502

- Daubs J. (1976). The sphygmomanometer in optometric screening. Australian Journal of Optometry. 59 (11), 393-97

- Hurcomb PG, Wolffsohn JS. The management of systemic hypertension in optometric practice. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2005;25(6):523-33

- Edmonds SA. Managing hypertension as an optometric physician. Primary Care Optometry News, 8th July 2014 https://www.healio.com/optometry/news/blogs/%7B92bc1204-742a-4307-9e65-145706fe3000%7D/scott-a-edmonds-od-faao/managing-hypertension-as-an-optometric-physician, accessed 16th April 2019-04-15

- Downie, LE, Douglass, A, Guest, D, et al. (2017). What do patients think about the role of optometrists in providing advice about smoking and nutrition?. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 37(2), 202-211

- Lawrenson JG, Evans JR. Advice about diet and smoking for people with or at risk of age-related macular degeneration: a cross-sectional survey of eye care professionals in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2013 Dec;13(1):564

- Gherghel D. An eye on pregnancy (2017). Optometry Today, September

- Bathia J, Sadiq MN, Chaudhary TA, et al. Eye changes and risk of ocular medications during pregnancy and their management. Pak J Ophthalmol 2007; 23.1

- Gherghel D, Sidhu S. Drug abuse and ocular health: awareness and recommended approach. Optician, 27, 01. 2017, pp 26-31.

- Fernández A, Sorokin A, Thompson PD (2007). Corneal arcus as coronary artery disease risk factor. Atherosclerosis. 2007 Aug;193(2):235-40

- Park YH, Lee YC. Images in clinical medicine. Lipemia retinalis associated with secondary hyperlipidemia (2007). N Engl J Med;357(10):e11

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. ‘Eye Disorders Linked To Statin Drug Use In Some Patients.’ ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 10 December 2008.

- David J Parkins, Curram R et al. The developing role of optometrists as part of the NHS primary care team OiP, Volume 15, Issue 4