‘If optometrists are to provide care to the elderly as they must, it is imperative that every optometrist receive formal training in geriatric optometry.’ (Verma, SB. Training Programs in Geriatric Optometry. Journal of the American Optometric Association, 1988, 59, 312- 315.)

Our elderly population leads a longer and more active life due to advances in health care; however, they are increasingly affected by various diseases associated with older age, including specific ocular conditions that can result in disability and blindness.

As eye care specialists, we have the choice to keep our elderly empowered, independent and healthy. Indeed, with our National Health Service (NHS) overstretched, there is an increasing need to expand our roles as healthcare providers. The General Optical Council (GOC) has stepped up to the challenge and allowed UK optometrists to embrace new clinical roles, including independent prescribing. In addition, high quality training and professional certifications are now available for a large number of clinical specialties, including those that are strongly linked to ageing such as glaucoma and low vision. Nevertheless, other areas of elderly care are not so well understood or consistently practiced. Therefore, the optometric management of some cases may well remain unsuccessful.1 In addition, specific issues such as dealing with patients with Alzheimer’s disease, stroke and falls, as well as detecting elder abuse and safeguarding the vulnerable and frail, should also be part of optometrists’ training.

This article will concentrate on presenting an overview of the most common systemic and ocular consequences of ageing. Tips on optometric management of the geriatric patient will be discussed in the second article in a forthcoming issue of Optician.

Geriatric population

The geriatric population is presently, somewhat arbitrarily, defined as a population aged 65 years and over. However, there is a large variety of opinion within the literature and clinical practice guidelines do not currently define ‘elderly’ or geriatric persons adequately. It has been suggested that several traits should be considered when identifying someone as elderly. These include:

- Physical changes associated with ageing

- Deterioration of normal essential physiological functions (such as stable heart rate and breathing)

- Changes in body weight

- Loss of muscular tone

- Decreased stamina

- Impairment of memory and cognitive ability

In addition, the degree of ‘social ageing’ (changes in how individuals interact within general social, familial and other population groups) also contributes to defining and elderly person.2

According to an Office of National Statistics (ONS) report in 2018, in 50 years’ time, there is likely to be an additional 8.6 million people aged 65 years and over, making up 26% of the total population. An ageing population represents an issue that puts significant pressure upon many sectors within society, the economy and public services, as well as upon a large number of healthcare departments, including optometry and ophthalmology. So what are the systemic and ocular consequences of ageing?

Ageing and systemic pathology with ocular consequences

Systemic diseases with ocular consequences that are due to ageing include hypertension and its complications, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, to list just few. Some of these disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease and stroke, have already been presented in this journal in detail (see Optician 21.04.17 and 19.05.17 respectively). A further update on two other common systemic pathological entities associated with ageing, systemic hypertension and diabetes mellitus, is presented here.

Systemic hypertension

Systemic hypertension is the most common vascular complication associated with advancing age. The prevalence of hypertension worldwide was estimated in 2015 to be 1.13 billion, with a 150 million people affected in Central and Eastern Europe. In the UK, hypertension affects one in four adults and its various related complications cost the NHS over £2.1 billion every year.3

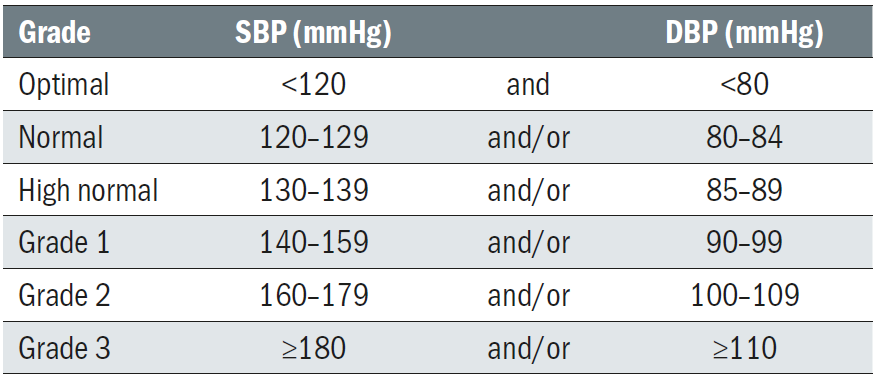

Hypertension is generally defined as clinic-measured systolic blood pressure (SBP) values of ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values of ≥90 mmHg. Nevertheless, according to the new European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension Guidelines published in 2018, hypertension is best defined as the ‘level of BP at which the benefits of treatment (either with lifestyle interventions or drugs) unequivocally outweigh the risks of treatment, as documented by clinical trials.’4 These guidelines also proposed the a classification for systemic hypertension outlined in table 1.5

Table 1: A classification of systemic hypertension 5

Hypertension is associated with a large number of complications, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke, both with important ocular consequences and both with a higher prevalence in elderly people. The European Guidelines on CVD Prevention have recommended use of the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) system because it is based on large, representative European cohort data sets.4 The SCORE system estimates the 10-year risk of a first fatal atherosclerotic event in relation to age, sex, smoking habits, total cholesterol level, and SBP. This score can be accessed here: http://www.escardio.org/Guidelines-&-Education/Practice-tools/CVD-prevention-toolbox/SCORE-Risk-Charts.

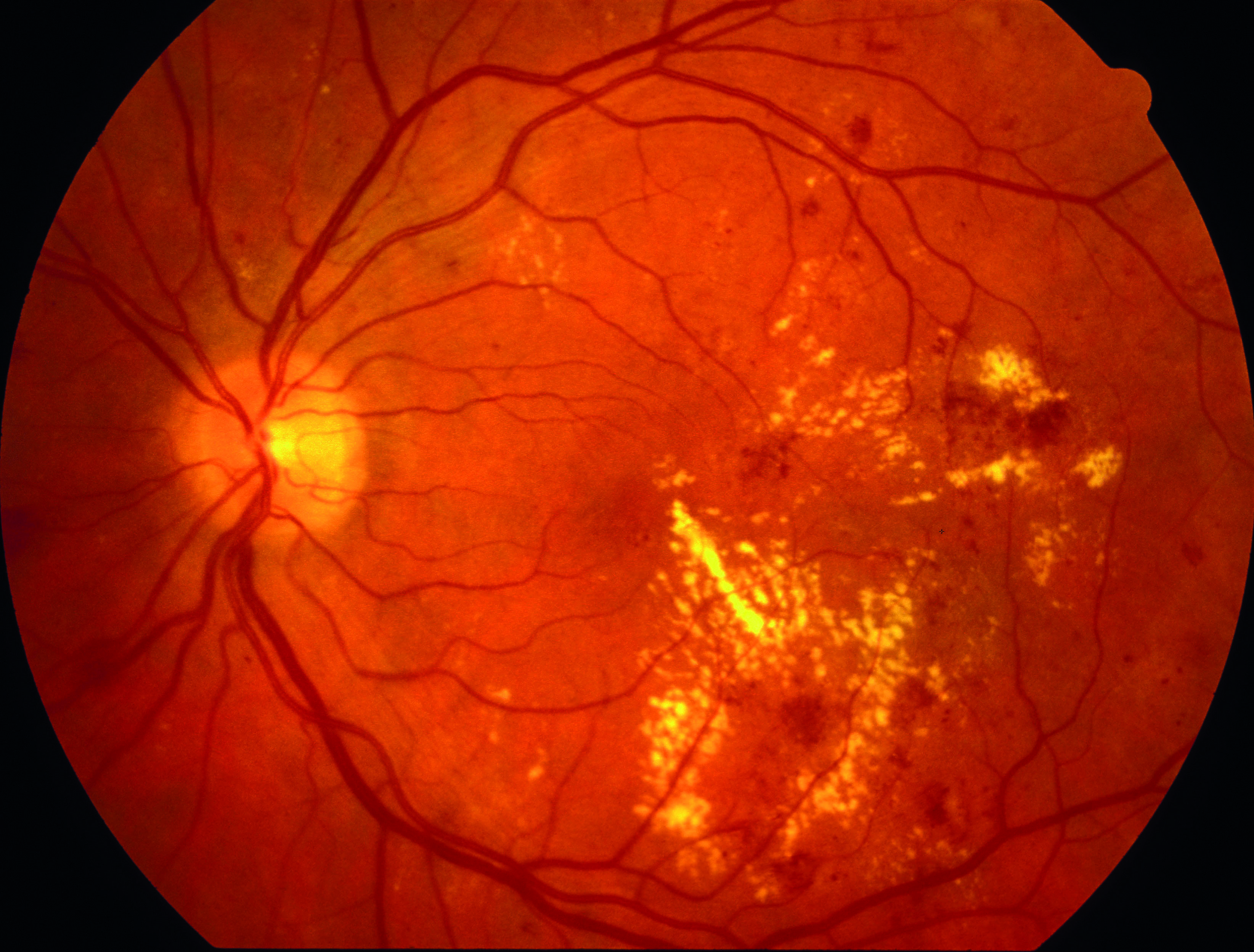

Besides assessing the presence of hypertension retinopathy (figure 1), optometrists should also be actively engaging into early detection of hypertension and follow-up. More details will be offered in the part 2 of this series.

Figure 1: Assessment of hypertensive retinopathy is best undertaken by eye care practitioners as part of a more general assessment of hypertension

Diabetes mellitus

According to figures published by the British Geriatric Society in 2018, half of all people with diabetes in the UK are aged over 65 years, and a quarter are over 75 years of age. The Society also emphasises a number of other important characteristics of elderly diabetic patients, which optometrists should be aware of. These include:

- Increased frailty

- Abnormal tolerance to standard therapies

- Decreased ability to self-care and self-medicate

- Lack of benefit from patient education programmes

- The existence of other co-morbidities which may be particularly challenging for patients and practitioners

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the fifth leading cause of blindness worldwide6 and its management, regardless of the patient’ age, depends on the level of retinopathy (figure 2). Nevertheless, considering the frailty and the likely existence of other pathologies, managing these patients is a very challenging process and involves an entire team of specialists. Therefore, eye care professionals should keep up-to-date and be confident with both patient-centred care and inter-professional communication principles and skills.

Figure 2: Diabetic retinopathy is the fifth leading cause of blindness worldwide

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a range of features. Motor features include:

- Tremor

- Rigidity

- Bradykinesia (slowness of movement)

- Postural instability

Non-motor features include:

- Disorders of mood and affect

- Cognitive decline

- Sensory dysfunction

- Autonomic failure

- Visual hallucinations

This disorder is associated with a range of ocular abnormalities,7 including:

- Dry eye

- Oculomotor disturbances, such as:

- convergence insufficiency

- abnormal saccades and smooth pursuit

- up-gaze limitation

- diplopia

- Abnormal contrast sensitivity

- Colour vision defects

- Glaucoma

- Visual hallucinations7

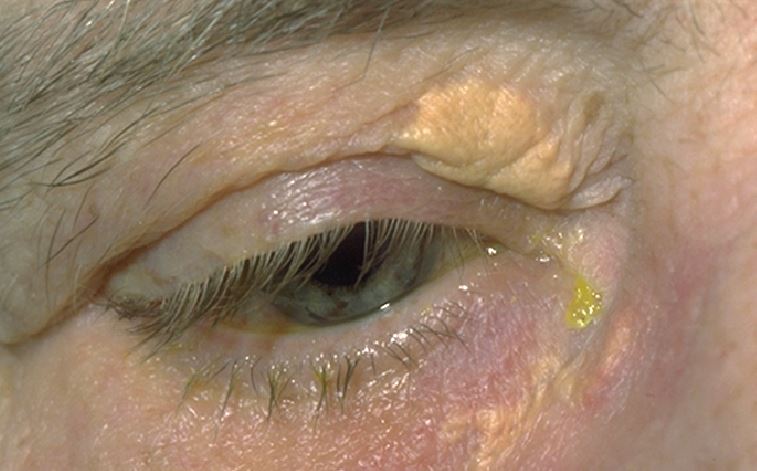

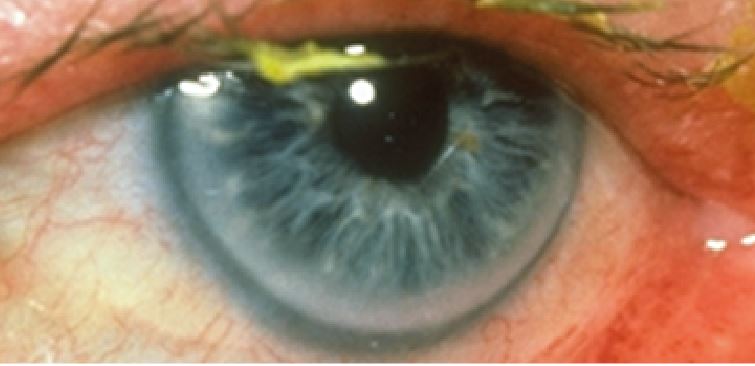

Figure 3: Xanthelasma

It is important that these abnormalities are diagnosed as soon as possible as they can usefully serve as predictors of disease prognosis.8 They also need to be managed appropriately, as they can have a major impact on a patient’s well-being and quality of life. Being able to maintain good vision is crucial in compensating for any loss of motor function in these patients. Indeed, it has been shown that over 80% of PD patients who suffered a fall over a one-year timeframe are visually impaired, compared with 66% of non-fallers.9

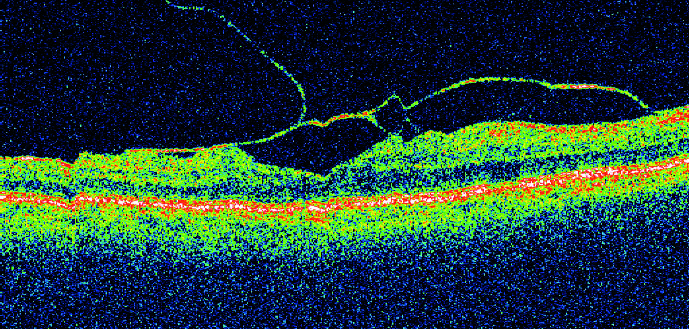

Figure 4 Posterior vitreous detachment

The role of eye care practitioners in diagnosis and managing ocular abnormalities in patients with PD is very important, as many patients do not report visual problems to their neurologist. In addition, the neurologist is not always looking in detail for all the ocular pathologies that these patients may display. This may result in suboptimal management and a decreased quality of life.7

Figure 5: Arcus

Ocular abnormalities associated with ageing

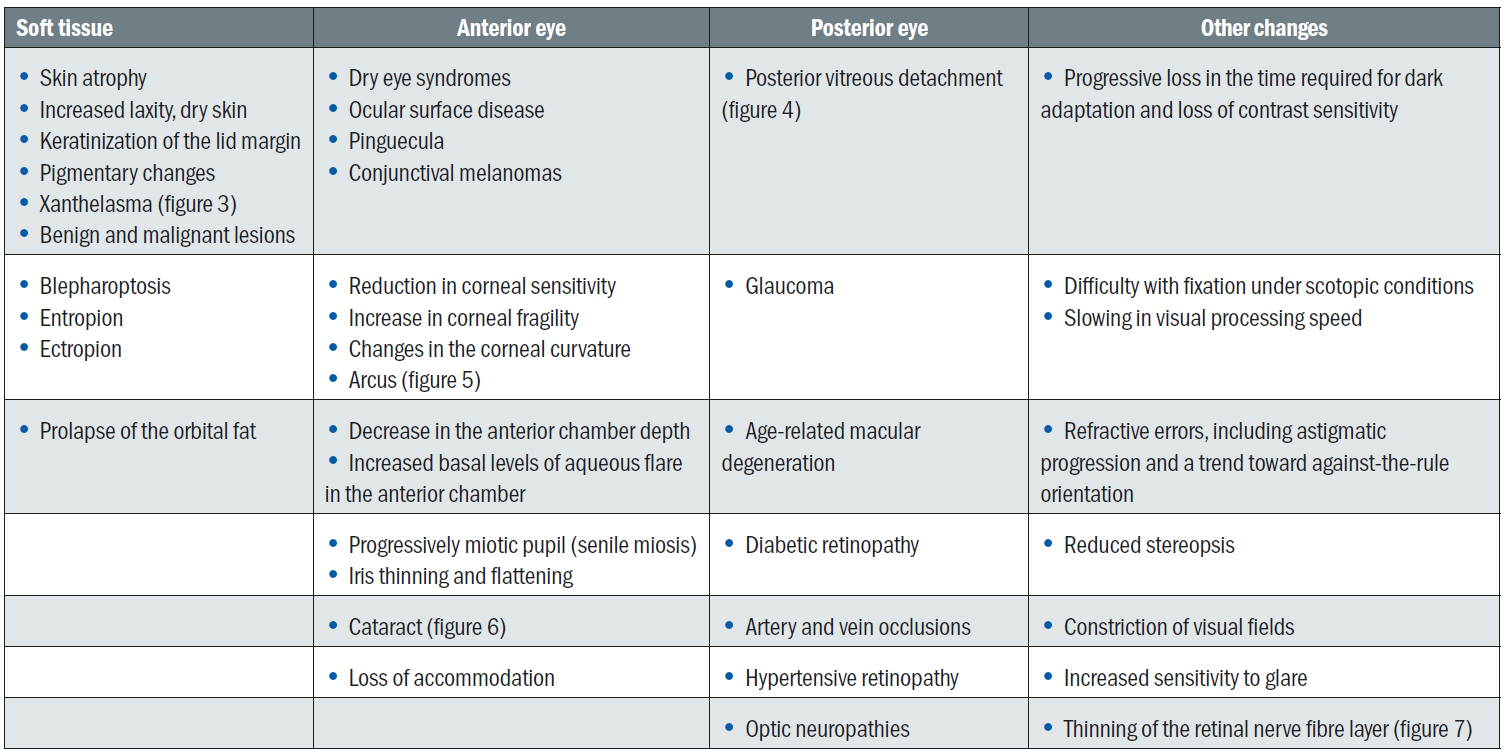

The most common age-related physiological and pathological changes occurring at the eye level are listed in table 2.10-12 From this table, specifics of glaucoma diagnostic and management in elderly have been previously published in this journal (see Optician 27.07.18). Other common disorders are listed in brief, as their detailed description is beyond the scope of the present article.

Table 2: Common ocular abnormalities associated with age (adapted from references 10 to 12)

Other geriatric concerns

Dual sensory loss

Vision and hearing loss often coexist in elderly patients and, when this happens, the end result is an increase in the functional impact of either when considered in isolation.13 Indeed, the presence of both impairments is associated with impaired communication, a loss of independence, an increase in depression, isolation, cognitive impairment and even in the likelihood of mortality.14

These patients will represent a challenge for any practitioner. Eye care providers should be prepared to put in extra effort to manage these individuals, following the same principles of professionalism and good medical practice as for any other patient.

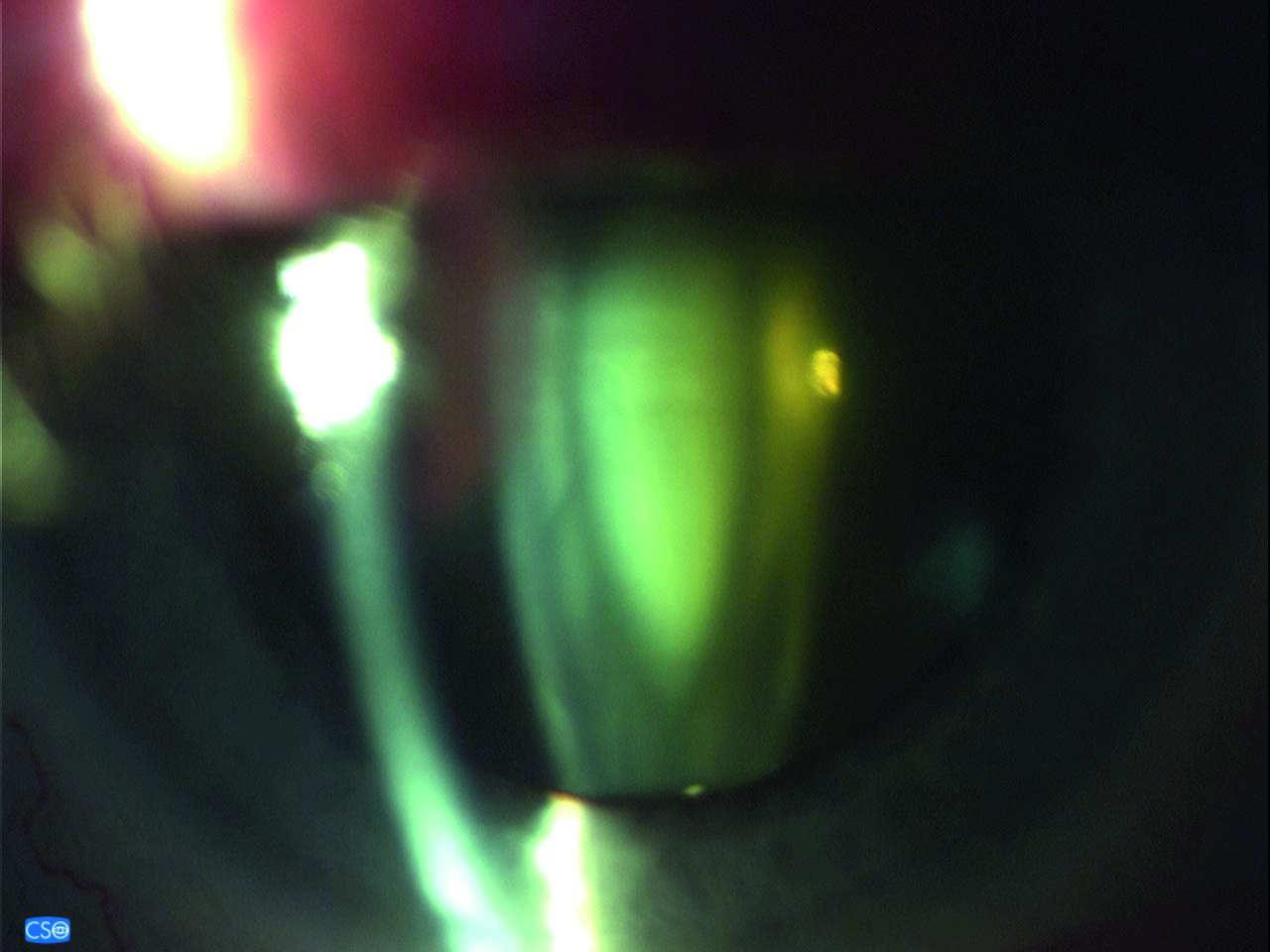

Figure 6: Cataract

Vision loss and depression

Depression is a pathology often unrecognised in elderly with vision loss. Nevertheless, it is estimated that about a third of elderly patients with vision loss experience symptoms of clinical depression and/or anxiety. This figure is double that of the general population.15 This problem is even more acute in elderly living in retirement homes or other institutionalised settings.16

Besides the impact that vision loss and depression have on patients’ life when considered individually, when combined their effects even more are disastrous, affecting both the quality of life as well as the mortality rate of the affected individuals. In addition, it has been found that depression has a negative impact on patients’ vision, and elderly patients suffering from depression could experience worse vision decline over time.17

Eye care practitioners should be aware that vision loss can lead to depression and be able to recognise and refer such patients. This is, however, challenging when the patients do not ask for help as is often the case with a clinically depressed elderly patient. In addition, the clinician could mistake signs of depression with those of dementia or even dismiss them off hand as ‘old age’.14 Whenever suspicion is raised, the practitioner should ask focused questions, talk to the family and refer patients to their GP as soon as possible.

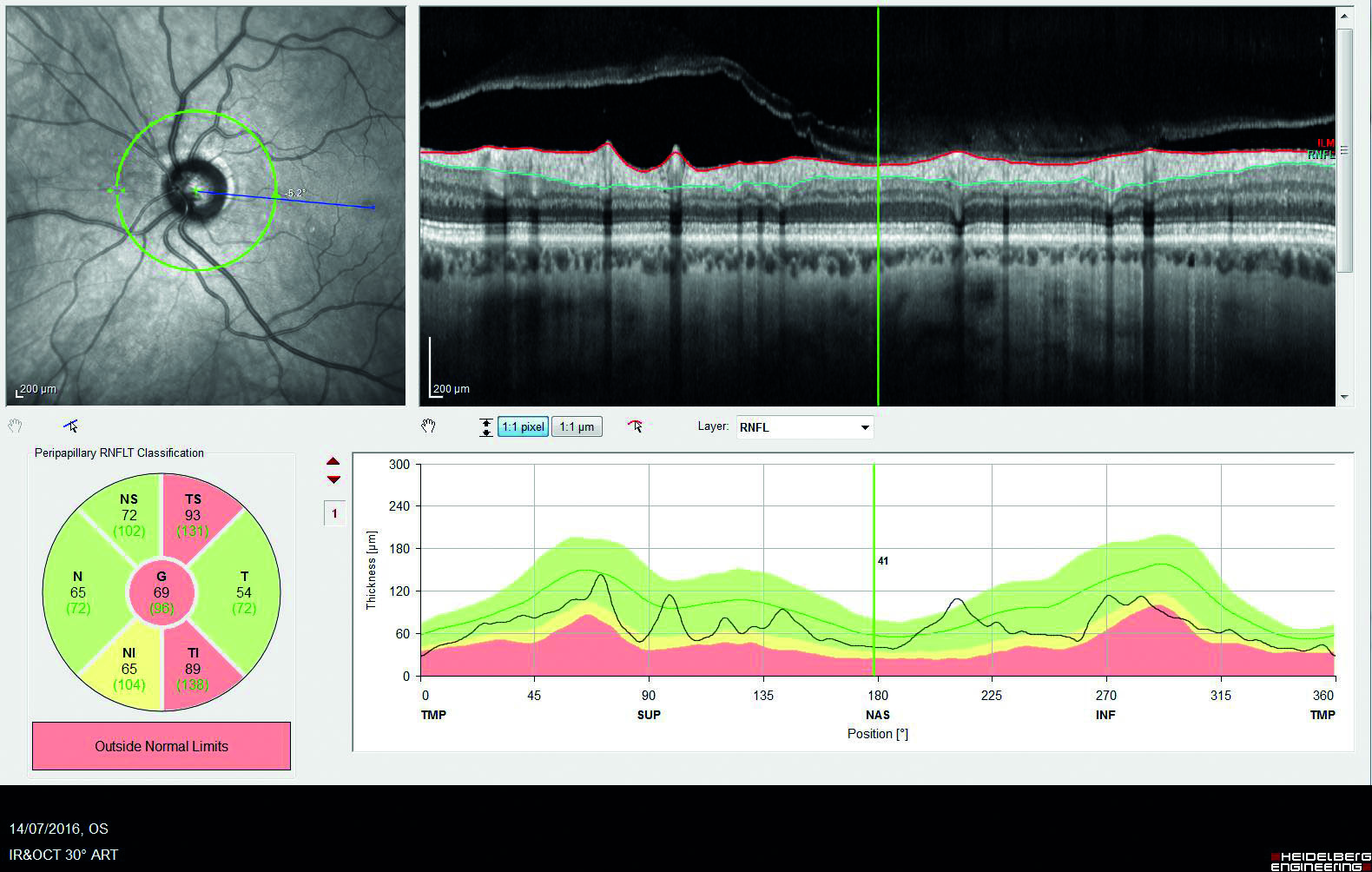

Figure 7: Thinning of the retinal nerve fibre layer

Visual disability and falls

Falls represent the second biggest cause of accidental death after road traffic accidents. It is estimated by the World Health Organisation that 646,000 people die from falls worldwide each year. The main causes for falls are as follows:

- Age-related issues – these include:

- loss of balance

- delayed reaction time

- changes in gait

- arthritis

- loss of vision

- dementia;

- Postural hypotension

- Stroke

- Heart attack

- Medication that affect mental alertness or blood pressure

- Others, including:

- alcohol intoxication

- recreational drugs

- ill-fitted clothes

- obstacles and hindrance to mobility

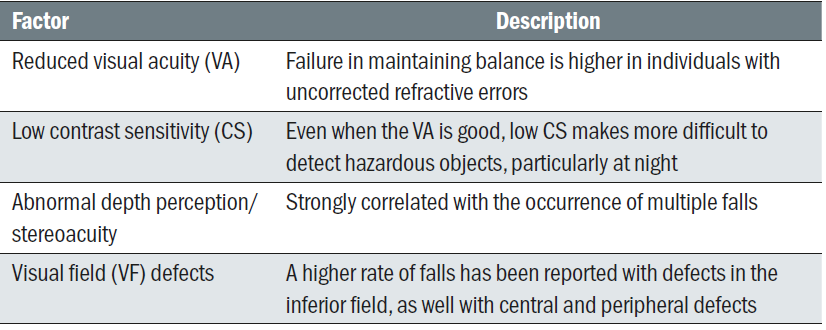

Visual factors for falls in ageing eyes are listed in table 3.18

Table 3: Visual influences on falls

The College of Optometrists website includes a section entirely dedicated to vision and falls. Practitioners can access this at www.college-optometrists.org/the-college/policy/focus-on-falls.html. The College have also published a leaflet on ageing eyes and falls and this would prove useful to many patients. A presentation on how eye care practitioners can help to prevent falls can be viewed at www.youtube.com/atch?v=cbfDJEC4dDY.

Ocular signs of physical abuse in elderly

According to the World Health Organisation, ‘elder abuse represents a single or repeated act or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person.’ The incidence of elder abuse is increasing, and this is thought to be due to a significant rise in hospital admissions and nursing home placements of elderly individuals.

General signs of physical abuse to be aware of include:

- Unexplained injuries and bruises, at different stages of healing and in unusual places

- Injuries to head and face

- Hand-slap marks, pinches or grip marks, burns, blisters

- Recoiling behaviour response to any physical contact

- Stress or anxiety signals in the presence of specific individuals

Ocular signs that may indicate physical abuse in elderly patients include:

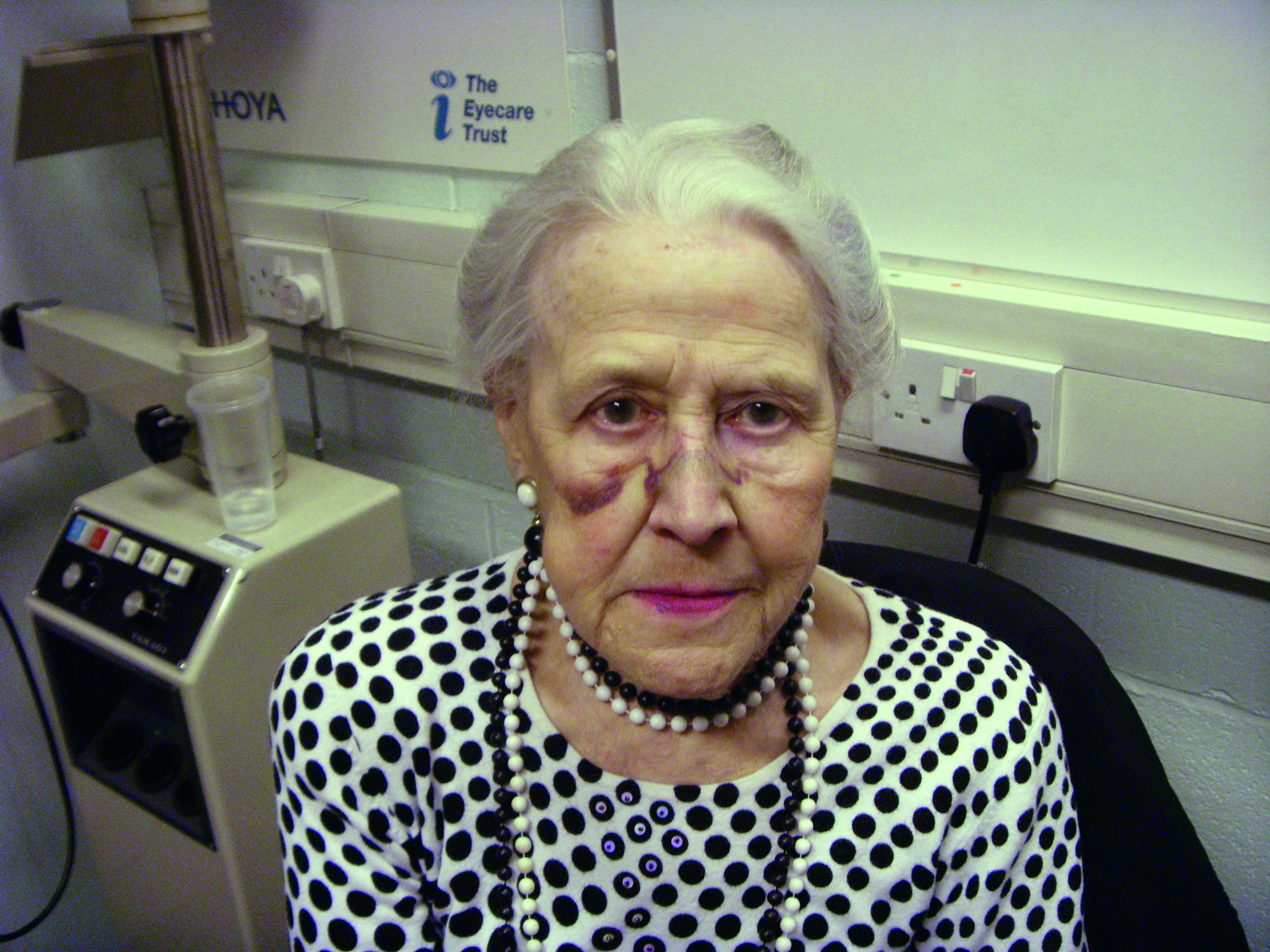

- Peri-ocular bruises (figure 8) or lacerations that are otherwise unexplained

- Lens dislocation

- Hyphaema

- Orbital fractures

- Broken eyeglasses and frames

Figure 8: Peri-ocular bruising

Importantly, it is very difficult to attribute the above to abuse with certainty, especially when the individual under concern also suffers from chronic medical conditions that might also explain the existence of such signs. Nevertheless, through a thorough history, observation of the patient’s behaviour, as well as a competent and complete examination and diagnosis, the eye care practitioner ought to be able to differentiate between actual abuse and other causes of physical harm.

The Optical Confederation has published a document that offers guidance on protecting children and vulnerable adults, updated in 2017, which can be viewed at www.opticalconfederation.org.uk/downloads/oc-safeguarding-guidance---updated--june-2017.pdf.

Conclusions

Geriatric optometry is a field that deserves in depth exploration. Eye care practitioners should be fully prepared to understand the specific characteristics of common pathologies associated with ageing, and be able to adapt their assessment and management to best meet the needs of elderly patients. Unfortunately, although this speciality is widely taught abroad, in the UK it is only now starting to be recognised as an emerging need. This is resulting in specific courses being launched (see www2.aston.ac.uk/study/courses/geriatric-optometry-standalone-module for an example). In addition, practitioners may also find some useful practical information on dealing with the ageing patients on the DOCET site (https://docet.info/course/search.php?search=ageing).

Ageing should not be a discriminating factor and elderly patients should be treated with the same considerations as all the others. In addition, special care should be taken to ensure that practitioners deal adequately with specific sensitivities and dignity issues that these patients might require.14

Dr Doina Gherghel is an academic ophthalmologist with special interest in inter-professional learning for optometrists. She also leads the new Geriatric Optometry module at Aston University.

For further information, go to pgadmissions@aston.ac.uk.

References

- Gherghel D, 2017. Newly qualified optometrist? Thinking of specialising?... Geriatric optometry in the UK. Optical News, 9th Nov. Available at http://resources.prospect-health.com/blog/newly-qualified-optometrist-thinking-of-specialising...-geriatric-optometry-in-the-uk-an-increasing-need-by-dr-doina-gherghel. Accessed 4th July 2019

- Schmitt EP, Castillo RE. Primary vision care in geriatrics: an overview. In Rosenbloom & Morgan’s Vision and Aging, p1-30

- Public Health England. Health matters: combining high blood pressure (2017). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-combating-high-blood-pressure/health-matters-combating-high-blood-pressure. Accessed 3rd July 2019

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W et al (2018). 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal; 39: 3021–3104

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K et al. (2013) ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal; 34: 2159-2219

- Leasher JL, Bourne RR, Flaxman SR et al (2016). Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by diabetic retinopathy: a meta-analysis from 1990 to 2010. Diabetes Care; 39: 1643-1649

- Ekker MS, Janssen S, Seppi K et al. (2017). Ocular and visual disorders in Parkinson’s disease: Common but frequently overlooked. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders; 40: 1-10

- Weil RS, Schrag AE, Warren JD et al (2016). Visual dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Brain; 139: 2827-2843

- Wood BH, Bilclough JA, Bowron A et al. (2002) Incidence and prediction of falls in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective multidisciplinary study, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 72: 721-725

- Haegerstorm-Portnoy G, Morgan MW. Normal age-related vision changes. In Rosenbloom & Morgan’s Vision and Aging, p 31-48

- Giese MJ, Wu SM. Anterior segment diseases in the older adult. In Rosenbloom & Morgan’s Vision and Aging, p 93-104

- Hasan SJ, Cohen JA. Posterior segment diseases in the older adult. In Rosenbloom & Morgan’s Vision and Aging, p105-131

- Turunen-Taheri S, Skagerstrand A, Hellstrom S et al (2017). Patients with severe-to-profound hearing impairment and simultaneous severe vision impairment: a quality-of-life study. Acta Otolaryngol; 137: 279-285

- Singh MK, Lee AG (2019). Visual loss and depression. In Geriatric Ophthalmology: a competency-based approach. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, pp71-80

- van der Aa HP, Hoevben M, Rainey L et al (2015) Why visually impaired older adults often do not receive mental health services: the patient’s perspective. Qual Life Res; 24: 969-978

- Jongenelis K, Pot AM, Elisses AM et al (2004). Prevalence and risk indicators of depression in elderly nursing home patients: the AGED study. J Affect Disord; 83: 135-142

- Zheng DD, Bokman CL, Lam BL et al (2016). Longitudinal relationships between visual acuity and severe depressive symptoms in older adults: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Aging Ment Helath; 20: 295-302

- Saftari LN, Kwon OS (2018). Aging vision and falls: a review. J Physiol Anthropol;37: 11