This year we have been publishing the first articles in a series (written by Dr Fergal Ennis) looking at the nature of binocular vision and the various ways it can be assessed. This week, we launch the first of a short series of interactive exercises with the aim of encouraging discussion about how binocular vision is assessed and managed in practice situations.

What is binocular vision?

In the first of our series (Optician 15.03.2019), Dr Ennis gave an overview of the nature of binocular vision and explained how an understanding of the normal state will help when assessing and interpreting anyone where there may be an apparent compromise or imbalance in their binocular vision status. He began by asking what we actually mean when we talk about binocular vision.

There are many potential definitions of the term ‘binocular vision’, but for the purpose of these articles, I will adopt the widely accepted clinical understanding of binocular vision as the condition where, with regards to the monocular visual fields, there is a large area of binocular overlap which is used for the coding of depth. The term ‘coding of depth’ can be roughly equated to ‘stereopsis’, the ultimate aim of binocular vision. In this definition, natural viewing conditions are assumed, ie that there are no impediments to either eye. In this state, the eyes are allowed to be associated, as opposed to dissociated, where there is an impediment that abolishes any possibility of binocular vision. For example, occlusion of one eye in the cover test dissociates.

Two fundamental requirements for the extraction of stereoscopic information while in the associated state are the presence of:

- Motor fusion – involves the control of the extra-ocular muscles to adjust eye position to maintain association.

- Sensory fusion — a more abstract concept whereby the brain processes both retinal images in order to extract this stereoscopic information.

Compromise of one or both of these two requirements generates the vast majority of binocular vision issues. Although these two distinctly different aspects of binocular vision can be described independently on a theoretical basis, and both have fundamentally different clinical investigations associated with them, we will see that these two components are inextricably linked in normal binocular vision. As one aspect becomes more compromised, so will the other. Indeed, neither aspect can function in the complete absence of the other. Although this interaction may seem like an unwanted complication, it has the hidden benefit that knowledge about one aspect may allow us to infer something about the other, without direct evidence. Perhaps the most important example of this is the fact that observation of motor fusion proves that sensory fusion must be occurring. This gives objective evidence of an otherwise invisible function of the brain.

The importance of understanding motor and sensory fusion and their interactions cannot be underestimated. Understanding these two functions is fundamental to understanding normal binocular vision, and then the signs, symptoms and investigation of compromised binocular vision.

The complete version of this article forms part of the source material for this new exercise and is accessible when completing the exercise. Along with two further references looking at assessment and expected norms.

What is normal?

An important indicator of a binocular vision concern is asymmetric acuity or vision. As Ennis points out, visual acuity is important in two respects.

First, reduced visual acuity will make sensory fusion difficult, especially if the visual acuity is asymmetrical as flat fusion requires two broadly similar retinal images. If sensory fusion is compromised in this way, then motor fusion may become compromised too. This could then lead to a phoria breaking down to a tropia, with the subsequent loss of binocularity.

Secondly, the visual acuity reduction may be due to pathology, or it could be due to amblyopia. This is a condition characterised by reduced visual acuity without any latent or manifest disease of the eye or visual system. This is diagnosed by the elimination of refractive error or pathology, and preferably supported by the identification of an appropriate risk factor. The most common risk factors for amblyopia are a constantly blurred retinal image (usually due to uncorrected hypermetropia or astigmatism) or heterotropia that has led to constant suppression of the non-dominant eye in order to eliminate diplopia. The risk factor must be present during the early years of development of the visual system, and if amblyopia is not resolved during these early years, it becomes a lifelong visual impediment to vision and binocularity.

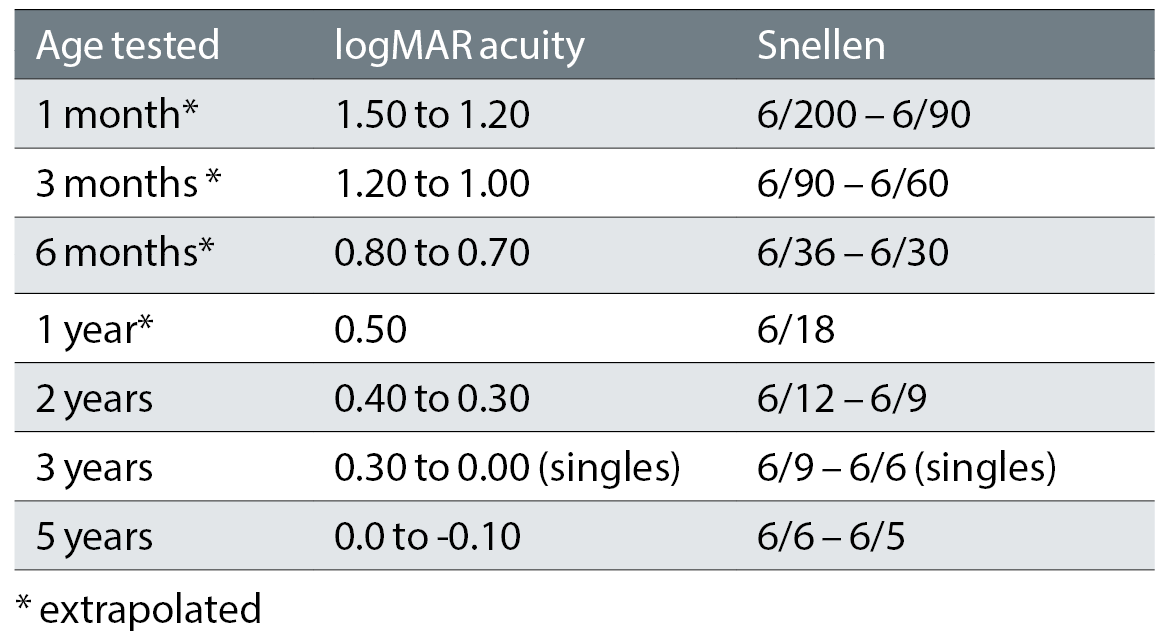

It is, therefore, useful to know what the expected levels of vision might be for the younger patient (see table 1). Where such levels are not met, further investigation needs to be undertaken to establish the likely cause of reduced acuity.

Table 1: Expected vision for different ages

Assessment

There is still some variation in how the vision of younger children is screened, with a few areas have an implemented screening programme, and other relying solely upon the parent to identify if they feel there may be a problem. Whatever the local situation, practitioners need to be prepared to assess younger patients who are attending because of a concern over the level of vision of the child or if there has been suspicion raised about the eyes being ‘straight’ or if one eye ‘appears to be turning’.

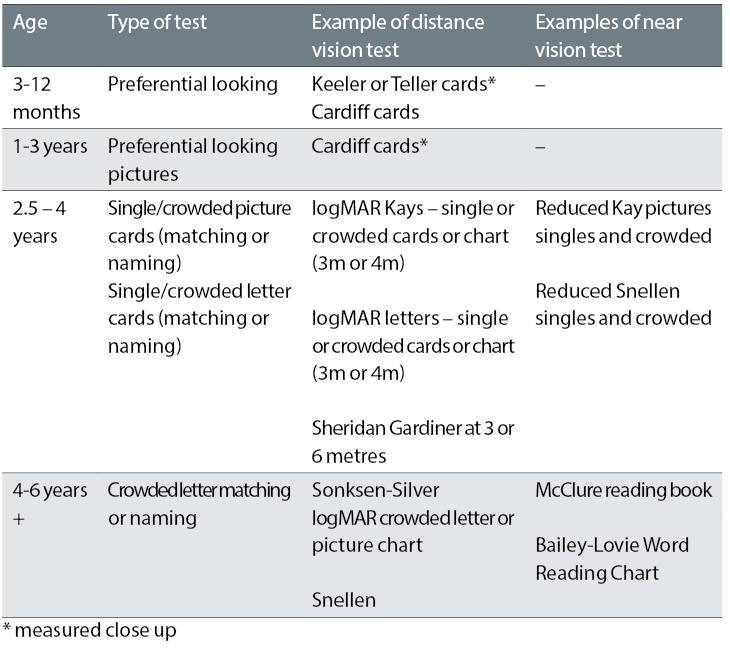

The accuracy of assessing the vision is very much dependent upon the careful choice of the appropriate testing chart (see table 2). Influences on test choice include the child’s age, understanding of the test, and their cooperation. More details of this are offered in the other source references for this exercise.

Table 2: Age-specific acuity tests – tests in bold are the preferred option

Interactive Exercise

An interactive exercise is available online related to the examination of a young child with asymmetric vision. A brief case scenario for your discussion has been designed to focus on what to tell the mother of a young child regarding having an eye check. The two main points of focus are:

- How to communicate to the mother and child about the tests to be undertaken and what the possible outcomes might be.

- Being able to predict the most likely possible causes for the vision difference.

This exercise is designed to encourage discussion by both optometrists and dispensing opticians as either group might be expected to deal with the challenges represented by these two areas of interest.

Before you attempt the exercise, there are six multiple choice questions which assess an overall understanding of paediatric assessment. To ensure successful completion, the relevant source materials are available:

Remember:

•There is no one single answer for your discussion, but what is needed is a reflection of your discussion (which must be for a minimum of ten minutes please) that is sufficient evidence of the various points having been covered.

• Read the source material available

• Complete six multiple choice questions to confirm you have grasped the main concepts

• Read the case scenario about which you are to confer with a registered colleague (for at least ten minutes please)

• The exercise is designed for both optometrist and dispensing optician so please ensure your discussion is relevant to your own role and responsibility

• Confirm with us the name and GOC registration number of the colleague with whom you have discussed the case and also write some short notes on the outcome of your discussion

• At the end of the month’s active period we will confirm that your discussion outcome meets the requirement for an interactive point

• Look out for a published discussion based on all responses in a future issue of Optician.