This series of articles doesn’t focus on how the eyes work, but rather on how the brains of the people who try to keep the eyes of other people seeing work. Its premise is that decision making is a skill that can and should be developed. It is my personal view that for clinicians the ability to make good decisions with what they know is more important than how much they know.

As a first step to making better decisions, it is vital that we understand how decisions are usually made and the predictable bias and limitations of our default way of thinking. A study of these processes reveals a subconscious level of mental laziness that habitually makes overly simplistic assumptions. This is a fact for everyone, and it isn’t a character flaw or cognitive fault, rather it is a necessary concession to rationality that allows us to somehow interact with the infinite complexity of the world. It is a marvel that in most circumstances the rapid answers that come to mind are usually good enough…but not always.

The danger of our customary way of making decisions is not their methods, but that their underlying assumptions and generalisations are hidden from us. This means that we aren’t very good at recognising when our first thought is likely to be suspect. In matters of thinking we are largely blind to process.

The good news is that through awareness and consistent practice it is possible to better identify these situations and through purposeful deliberation make allowances and corrections. It is important to note the reference to practice because decision making is a way of acting and so improvement is reliant on doing. It may be helpful, but it isn’t possible, to become a good decision maker by only reading; rather you need to make decisions.

The first aim of these articles is to increase our tolerance with the shortcomings of ourselves and others that is revealed by hindsight. It is also hoped that they may provide instruction to lessen the frequency and impact of bad decisions. This can only benefit our patients and society.

An overview of decision making

Decision making is a judgement and a process

A decision isn’t simply answering a question with a factual answer as might be done in a quiz – you cannot cram for decision making. A decision involves a judgement that affects our behaviour. It involves choosing between options presented to us and oftentimes thinking up new options.

For many decisions in our clinics we don’t have access to all the relevant information and, unlike a quiz, there might not be a perfect answer. Different options usually have both good and bad points necessitating some trade-offs and sometimes the best decision is the option that’s least bad overall. The sorts of decisions that opticians and optometrists need to make are listed in table 1.

Table 1

A decision is more than its final judgement, rather it covers the stepwise and iterative processes and methods that lead to the judgement. Rational decision making should involve efforts to understand the problem, collect information and evaluate its credibility, identifying possible options, a probabilistic analysis of the alternatives, and a final selection with due consideration of mitigating risk.

Despite the terms being used interchangeably in everyday language, it is usual in decision theory to make a distinction between a decision and a choice. A decision is more than just selecting an option, any option, but intimates a deliberate analytical methodology and it follows that some decisions are objectively better than others.

In contrast, a choice is dominated by individual preferences. This distinction is simplistic because there are commonly elements of both decision making and choosing, but it remains a useful strategy to identify and consider these components separately; in particular, when making choices it should be appreciated that an obsession with gathering factual information and estimating probabilities is less helpful than clarifying personal goals and values.

Uncertainty in decisions

While our clinics may at times be manic, they are not chaotic in that there is a relationship between what is done and what happens. However, as with the rest of the world they don’t operate as a tidy flow chart where the consequences of our actions can be predicted with certainty.

It does not really matter whether this uncertainty is viewed as the influence of things that have not been considered, random chance or luck. More important is to acknowledge its ubiquitous presence that will forever cause decisions to be imperfectly correlated with outcomes, and thus the naivety or foolhardiness of overlooking its impact and not making allowances.

It follows that a good decision does not guarantee a good outcome and conversely a good outcome is no assurance that the decision-making process behind it was sound. A good outcome can occur due to misfortune and it’s not always the case that a bad outcome is the result of anyone doing anything wrong. These points need to be stressed because they run counter to our intuition.

The reality is that our clinics are more usefully considered to operate as casinos and despite the confidence imparted by our knowledge we all need to roll the dice. There is wisdom in realising that the best we can do for our patients is to gamble responsibly with their health and to not risk what they cannot afford to lose.

When considering the outcomes of others (or ourselves) our instinct is to applaud when things have gone well (more so with ourselves), and suspect negligence when they have gone awry unless we are involved when there is a tendency to embrace the influence of misfortune. While we cannot prevent these thoughts, through diligence we can make the effort to establish the habit of following them with a more intelligent review of how things were done given what was known and what remained unknown at the time, rather than only what happened.

What is a good decision?

The requirements of a good decision are summarised in table 2. An optimal decision delivers the best expected outcome, and in less favourable circumstances when nothing good can be achieved to deliver the least bad expected outcome.

Table 2

The reference to ‘expected’ outcomes, rather than ‘actual’ outcomes, is a humble acknowledgement of the omnipresent uncertainty in any decision. It refers to the decision that would produce the best outcome most often if that decision were repeated many times.

It necessarily follows that a willingness to improve our decision-making ability demands us to lift the comfort blanket of black and white thinking that obscures our perception and to consider probabilities. The objective of a decision is to maximise the probability of a good outcome and minimise the probability of a bad outcome.

This much is straightforward. The difficulties arise, not so much in the methods of computation, but because in our clinics we don’t have time to do the calculations and it is unlikely that the relevant probabilities will be known. Also, even committees of experts often disagree as to what the optimal outcome is and the relative importance of the array of consequences. Amongst other considerations, these difficulties mean that consensus on an optimal decision is rare.

However, this complexity does not support the relativistic view that all decisions are only opinions with equal validity. No. Some decisions are quite rightly recognised by all informed persons as sub-optimal and sometimes as bad, terrible or dangerous. A good decision is not merely a fashionable opinion, rather it reflects the shared life experiences that good things tend to happen when people act a certain way and that things do not usually work out so well when people do otherwise. Indeed, unless we have exceptional reasons to do otherwise, it is prudent to heed conventional wisdom as the default choice.

Conversely, the consensus on what should not be done is often firmer than what ought to be done. It follows that a pragmatic guide to making better decisions is to avoid doing anything that is obviously wrong, which is not too different to the advice that my elder brother would repeatedly offer to me: ‘whatever you do, don’t do anything stupid’. Stretching this line of thought beyond sibling advice, when at a complete loss of how to act, it can be useful to imagine the worst decision that could be made and then to do the opposite.

Some decisions only involve one person, but it is more typical that a decision will affect others and so these effects and their views should be considered. These others might be specific people, such as family members, or abstract groups like other patients who may have treatment delayed or denied when resources are finite. A good decision seeks to consider all relevant stakeholders.

Most decisions are based on assumptions and a good decision is robust to errors in these necessary best-guesses about how things are and how they might change in time or respond to an intervention. The degree of robustness should of course consider the importance of the decision, with a prescribing decision on a change in spectacle refraction warranting a less thorough review than when deciding how to manage a possibly swollen optic nerve head.

As an ideal, a good decision involves a process that can be communicated. Being able to unpack and articulate the component elements of a decision allow it to be understood and therefore to be reviewed for ways that it might be done better and for its limitations to be recognised.

The decision makers who consistently achieve better outcomes are characterised by a highly developed awareness of how they make decisions, which has of course been necessary for them to be able to question and refine their own reasoning. Also, in the event of a bad outcome, which given time is an absolute certainty, a communicable decision is a defendable decision.

An overview of decision makers

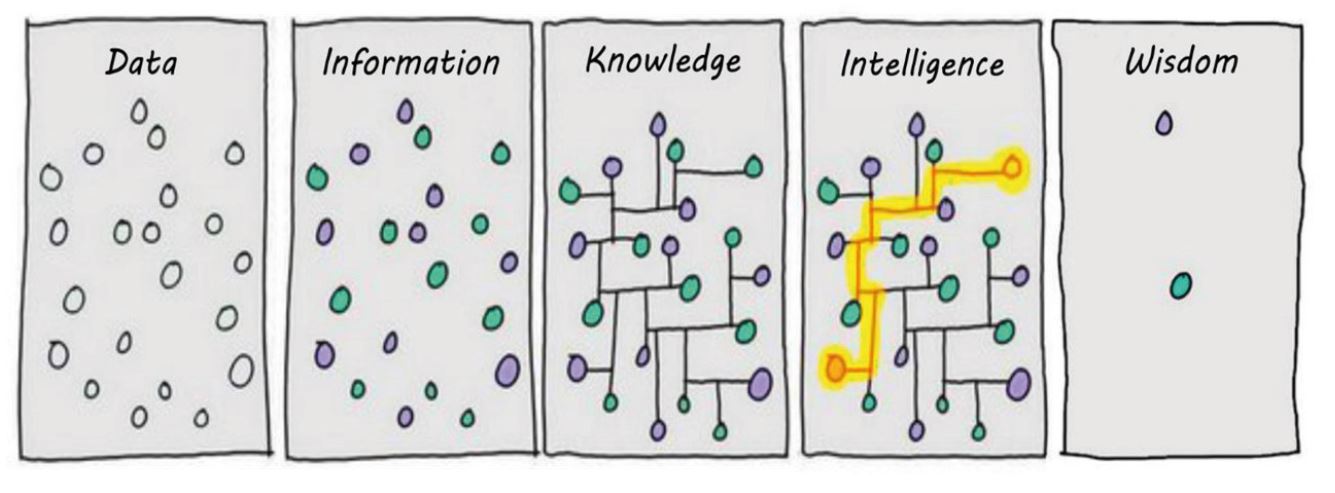

Knowledge – Intelligence – Wisdom (figure 1)

Figure 1: Data – Information – Knowledge – Intelligence – Wisdom

The raw material of everything we know about the world comes to us as unfiltered data, like numbers churned out of a machine. These numbers could mean just about anything, or nothing, and it follows that data remains unhelpful until it is transformed into information by the coupling with meaning, which is to say that information is data with a story.

Learning that the numbers on a visual field plot denote light sensitivity in different locations converts them from meaningless data to meaningful information.

The next level of understanding is the text-book knowledge that dominates our teaching at school and university. Our knowledge of the visual system lets us recognise and understand why certain patterns of visual field loss are associated with certain diseases. For example, we know that a visual field defect only affecting one eye must be pre-chiasmal before the visual information from the two eyes converge.

Knowledge may be good enough to pass examinations and is a pre-requisite for higher levels of understanding, but on its own it is insufficient to make good decisions or safe clinicians. It is possible to be very knowledgeable without being very useful. Intelligence moves beyond know-that to know-how and the ability to identify and solve problems. In doing this the results of tests are not considered in isolation but are instead considered in the context of the presentation and with information from other tests and sources.

A basic level of intelligent reasoning might be required to make a judgement on whether an apparent visual field defect reflects a real problem or is an artefact, which involves an assessment of the credibility of the test results and integration with supporting or contradictory evidence from other sources.

In doing this we are identifying an abnormality, judging something to be more likely to have a worrisome cause than to be a variant of normal or a consequence of test noise. As an example, a borderline visual field anomaly should be considered more likely to be real when it occurs alongside a suspiciously cupped optic nerve head and there is a family history of glaucoma, than in another presentation with an identical visual field result but no other risk factors for disease.

A more sophisticated level of intelligence needs to be employed following the determination of an abnormality to form a differential diagnosis that in turn allows for the identification of the most likely diagnosis and then to form, communicate and enact a management plan.

Developing the visual field example, when considering the most likely cause of a visual field defect a clinician should consider not only the results of the visual field test, but integrate this information with the demographic risk factors for various conditions, the examination of the retina and optic nerve, intraocular pressure, and the presence or absence of neurological symptoms.

Broadly speaking, knowledge refers to memory whereas intelligence is what is commonly thought of as thinking. It should be a goal of all members of every profession to not simply focus on the volume of what they can recall, but to develop their intellectual capability to use what they know to better address the needs and concerns of people.

Wisdom is the highest level of intelligence, which can be described as the ability to reduce complexities into fundamentals and to appreciate the context of any specific situation with due consideration of wider concerns. For a patient with chronic open-angle glaucoma, when deciding on management, a wise clinician will consider not simply the diagnosis, but the risk of significant visual impairment in their lifetime due to senectitude and co-morbidity.

Clinicians are defined by their actions

A young child often identifies a clinician as someone who wears a white coat, but with maturity they recognise that the definition is more reliably based on what people do, rather than how they dress. Similarly, a clinician is better identified by their regular behaviour than by any qualification.

A more useful description of a clinician is someone who is motivated to care for their patients and use their specialist knowledge to identify, define and creatively solve problems. Avoiding a problem doesn’t solve it, and so clinicians have to make decisions and choices, and this differs to a technician who is limited in their role or limited in their imagination to gathering information and following rules.

Clinicians must also be willing to take ownership of problems and see them through to completion, and to take responsibility for any decisions and choices made. A clinician requires both ability and attitude that together manifest in patterns of behaviour that consistently produce desirable outcomes for their patients.

The above begs the questions of why does is matter and why should we want to be a clinician when it might be possible to bump along as a technician? Certainly, the latter is a choice and so it isn’t my place to tell anyone on this matter what they personally should or should not do.

However, it is my experience that acting as a clinician is better for patients and is personally more rewarding, and it is my belief that to not develop that potential when it is latent or underdeveloped is to waste a gift.

Also, a brutally pragmatic analysis is that technician roles and technician aspects of our current jobs are increasingly being delegated and outsourced to less qualified and cheaper personnel and ultimately to computers and relatively basic artificial intelligence. It seems to me that we are being presented with a choice of moving forwards and developing, or vocational atrophy.

Limitations and compensatory strategies in decision making

Uncertainty

There is very little certainty in clinical practice other than there being no end of surprises. We often do not have access to all relevant information because we do not have the equipment, or the information is inaccessible as with subjective experiences that exist only within the minds of our patients. All tests are imperfect, patients do not reliably describe the expected symptoms that are listed in our text-books, eye problems manifest in a multitude of ways, sometimes there is more than one thing wrong, and the effects of our interventions aren’t reliable

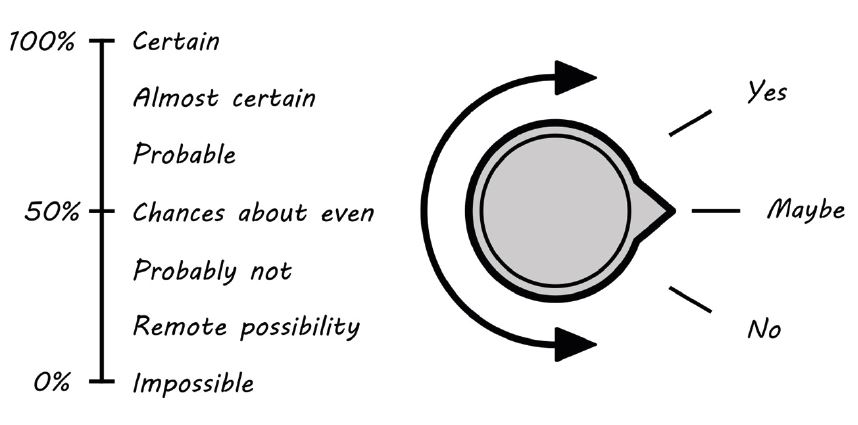

The only way to rationally operate in this fuzzy reality is to use probability, which is simply to insert the concept of ‘maybe’ into yes/no binary classifications (figure 2). Doing this is a revolutionary advance in categorical conceptualisation, but we need to go further because there are many degrees of ‘maybe’.

Figure 2: Moving beyond dichotomous classification

For example, some glaucoma suspects are very likely to have the disease whereas for others the chance is very slim. To lump them together in the same catch-all category lacks the refinement for clear communication to others and frustrates optimal management. It is a further improvement to use a range of descriptors to quantify different levels of ‘maybe’. The range of descriptors may include almost certain, probable, chances about even, unlikely, remote possibility, etc.

The choice of wording is only limited by imagination, and there is considerable variation is how different descriptors are used, and so with linguistic quantification there is always some uncertainty in grading uncertainty (Figure 2). Decision making specialists use numbers that remove this ambiguity and allow for computational manipulation.

Human limitations

Our bodies have natural limits on how fast they can run or how long they can keep going before becoming exhausted, and our minds are no different. Thinking is a resource limited activity. Biology places upper-limiting constraints on how our brains can work. We can only think so fast. If we think too much, we become fatigued and performance reduces. It is only possible for us to remember so many things in our short-term memories and our recall from our long-term memories is unreliable.

Owing to these limitations, not only is it unnatural for us to think and act within a rational paradigm all the time, using a logical and sequential cause and effect analysis, but it is impossible. If we had evolved otherwise then our ancestors would have been eaten whilst doing the maths of whether the lion would catch us if we ran away. Nowadays we would be paralysed with computational overload when negotiating a busy traffic junction.

It follows that instincts and emotions are not bad, and the rapid speed of their operation is sometimes essential for our survival. However, the trade-off of these ways of processing information is that by necessity they oversimplify complex decisions and rely on cognitive shortcuts, sometimes termed heuristics.

As clinicians, we should be mindful to not disregard our inherited intuitions that have been refined by millennia and usually get us to where we want to go, but need to appreciate that this way of thinking is and will always be the default way of thinking, and that it is and will always be vulnerable to unconscious bias that will sometimes send us off course.

Both words in the phrase ‘unconscious bias’ are very important. The shortcuts in thinking are done unconsciously, and so we are not aware that we are doing them. This blindness to process inclines us to readily accept our first answer as the right answer because we don’t realise how we cheated or even that we cheated at all. The appreciation of bias is important because this recognises how the effects of any shortcuts are not random, but rather tend to sway decisions in predictable directions. We consistently make the same mistakes in the same circumstances, and it is this predictability in how and when we err that allows good decision makers to employ compensatory strategies as a second-level of corrective thinking.

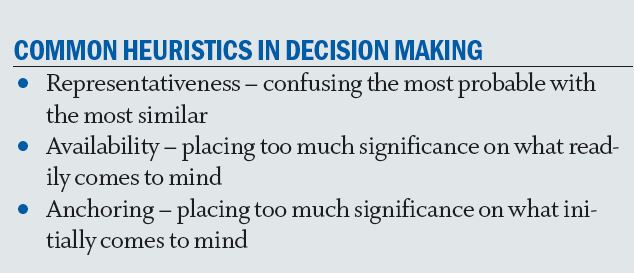

We instinctively use a great deal of heuristics, but perhaps the most salient ones in our clinics are those termed the representativeness heuristic, the availability heuristic, and the anchoring heuristic (table 3).

Table 3

The representative heuristic refers to our tendency to substitute how much something resembles a prototype that exists in our minds for how probable it is. In our clinics it typically leads us to think that rare diagnoses are more common than they are and to over-diagnose these conditions. Consider the following: a patient presents in community with a diffusely red eye and complains of pain that causes them to wake from sleep. This description very much fits the classic presentation for scleritis, and with this knowledge most clinicians would consider this to be the most probable diagnosis. However, scleritis is very rare in community and, in point of fact, presentations like this are more likely to be atypical presentations of episcleritis. Our default diagnosis was made upon how well the presentation matched the text-book description and disregarded the prevalence of the disease.

The take home message is that an unusual presentation of a common condition occurs more frequently than a typical presentation of a rare condition. The availability heuristic refers to how if something readily comes to mind then we are inclined to believe it. In our clinics it typically causes us to overdiagnose scary, and therefore memorable, diagnoses and whatever we have been thinking about recently.

As an example, serious cancers affecting the eyelids are rare, but following a particularly harrowing and graphic CET audio-visual presentation of how cancer can affect the eyelids I incorrectly suspected a metastatic process in almost all patients with asymmetric blepharitis the following week – and yet, in over 20 years of practice, I have seen less than a handful of confirmed cases (how many I have missed is unknown!). No doubt, the following week, I thought that everybody had another condition that happened to be at the foremost of my thoughts.

The anchoring heuristic refers to how we latch on to the first thing that comes to mind, or rely too heavily on the first piece of information that we are offered when making subsequent judgements. The problem is that, contrary to the adage, our first thought is not always our best thought. Our first thought is often based on intuitive guesses that are dominated by the representative and availability heuristics, and the problems with these have already been highlighted.

Other human limitations of decision making are rooted in the capital vices of laziness and pride. Making good decisions is not simply a talent but necessitates an inordinate degree of effort. It also demands honest introspection and listening to feedback and, when appropriate, that we admit we could have done better. In doing we so do not pass over the opportunity to learn from experiences.

Workplace limitations

The quality of decisions is also limited by factors pertaining to our work environments that may be quite separate to the limitations imposed by personal capabilities.

On this topic, I’m always reminded of a highly regarded corneal specialist who was asked how he’d treat someone with a microbial keratitis in private practice. He replied that he would not because his private clinics did not have the facilities to culture a corneal scrape to identify the infective organism and was not able to offer 24/7 overnight admission.

This is an example of a wise and obviously competent individual considering not just what he is qualified and capable of doing, but also what he can and cannot do in a specific workplace setting. A similar example from community practice might be a lower referral threshold for a person complaining of new distortion when an OCT scan is not available to confidently exclude wet AMD.

Summary

This first article in the series may appear to paint a somewhat gloomy picture; that our impulsive irrationality and environmental restrictions forever checks our ability to consistently make good decisions. In truth, I think that they probably do, and this demands humility, but it is my impression that any natural limit is way above what most of us regularly achieve and the fact is that most optometrists and opticians already do not do so bad without purposeful effort. Overall, as a profession and industry sector we are getting by, but we can do much better.

Subsequent articles will review the importance of appropriate problem framing and the prioritisation of outcomes, and makes suggestions based on the predictability of our irrationality that offer corrective strategies.

Dr Michael Johnson is a therapeutic optometrist working in independent practice in South Gloucestershire.