The increase in our elderly population puts significant pressure on the many and various health care providers with responsibility for their care. Primary care services are the first stop for health complaints; among these, optometry is the discipline in charge of detection and appropriate referral of all ocular abnormalities and also certain systemic conditions that can manifest themselves within the visual system.

Such conditions are more numerous in elderly individuals, and eye care practitioners should be prepared to deal not only with the presenting diseases, but also any other healthcare needs that ageing individuals may have. Therefore, the education system needs to provide all the necessary tools to enable eye care providers to step-up to the challenge. Curriculum models for the inclusion of gerontology into the mainstream of optometric education were first introduced in 1985.1 However, more work is necessary to allow eye care practitioners to be confident when providing services such as patient education and lifestyle advice. They also need to develop skills for detecting early signs of decline in the well-being of the geriatric patient, such as evidence of social isolation, depression or abuse.

Moreover, eye care practitioners should learn to address each patient holistically, rather than just a pair of eyes. For this to be successful, good interprofessional communication is important where co-management of a patient is indicated. Indeed, a multidisciplinary approach to each case should become the norm.

This article will offer a few important general pointers for the best care of geriatric patients attending optometric practices. Existing geriatric optometry taught programmes should be considered for gaining better knowledge of the subject.

Adapting the practice to the elderly patients’ needs

It goes without saying that we have an important duty to anticipate the needs of all our patients, regardless of their general ability. Therefore, simple measures to facilitate an elderly patient attending for an eye test need to be in place. These may include:

•Access ramps

•Clear signage

•Contrasting colour for doors and other access routes

•Good lighting

•Accessible bathrooms with elevated toilet seats and grab bars (figure 1) should be available in all practices

•Facilities for hearing and/or vision impaired patients

Figure 1: Adapted toilet seats ensure bathrooms are suitable for the elderly and infirm

Booking longer appointment times will help ensure best care for hearing and/or visually impaired patients as well as those with impaired memory.

Many elderly patients have mobility problems. Therefore, our consulting rooms should be adaptable, in the sense that instruments should be able to be moved to the patient, in various positions and at various heights.

History taking

A good history taking is crucial for the success of our patients’ management. The Directorate of Optometric Continuing Education and Training (DOCET) has published a good guideline of how to communicate with the older patient. This material can be accessed by optometrists here: https://docet.info/course/view.php?id=78.

The eye care practitioner should show interest and empathy while maintaining knowledge and professionalism. This is important in establishing a rapport and make it easier when a patient needs help with opening up. Elderly patients often do not report all their symptoms or concerns because they put them down to the natural ageing. Nevertheless, ‘no symptom should be attributed to normal aging unless a thorough evaluation is done and other possible causes have been eliminated.’2

Beside the reported reason for attendance and the patient’s past and current ocular and general health, the patient’s lifestyle should be thoroughly explored through appropriate questions. The patients should be asked to bring to the test as much information as possible about current medications, any hospital letters and so on. During this process, it is important to note the patient’s reactions and body language. It should be kept in mind that elderly patients may not always be able to remember past symptoms and treatments, or may deliberately fail to report them because they are afraid of hospitalisation, an outcome viewed with a degree of fear by many old patients.

Encouragement and praise should be given, when appropriate and without patronisation, to allow the conversation to flow. From time to time, summaries of the findings so far should be given to the patient. In this way, the patient will feel at the centre of his or her own care and this will encourage fullest participation with, trust in and commitment to future management plans. Gaining trust, often in a limited time period, requires training, clinical skill, experience and a genuine empathy and willingness to help each patient.

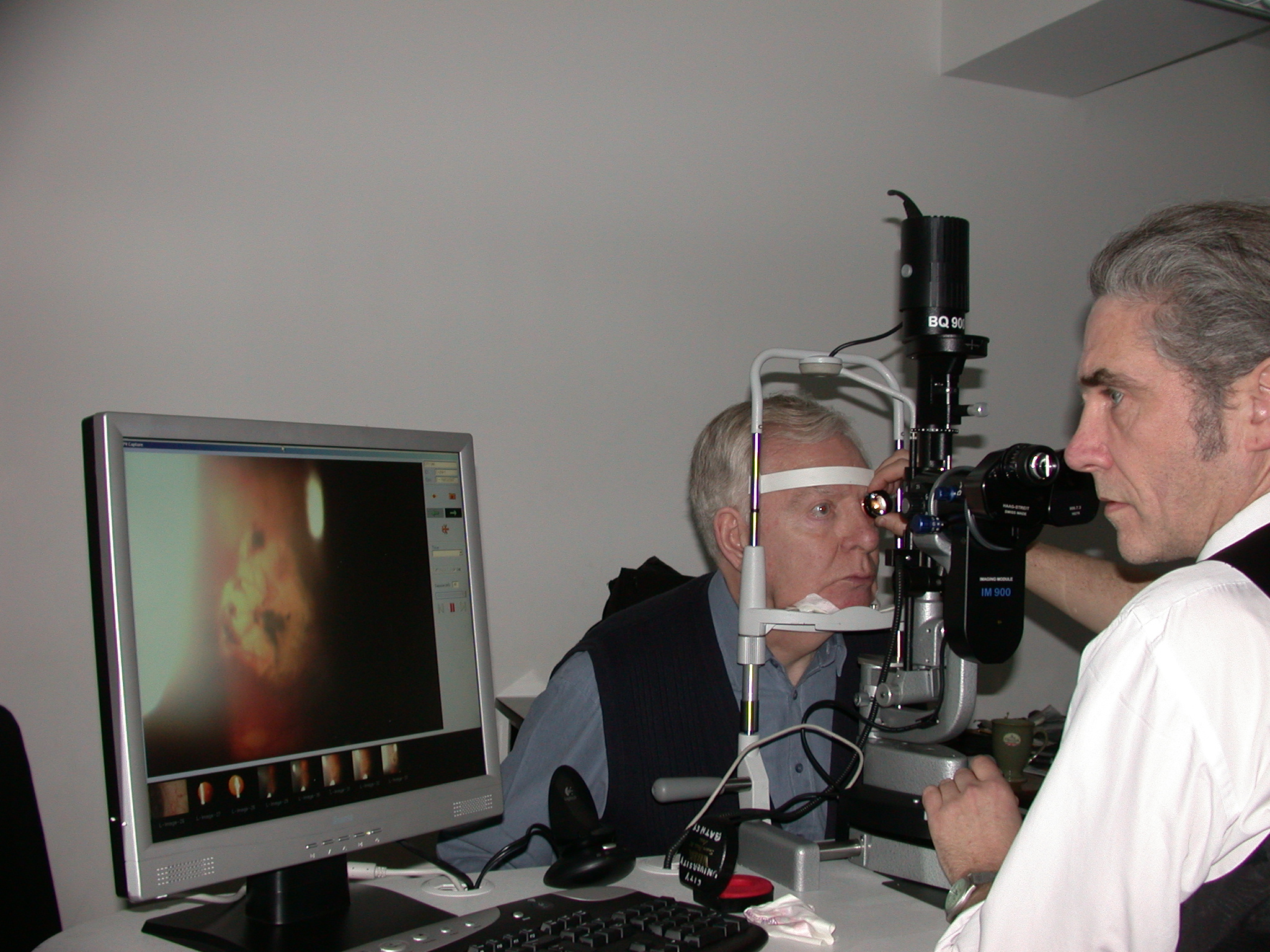

Ocular Examination

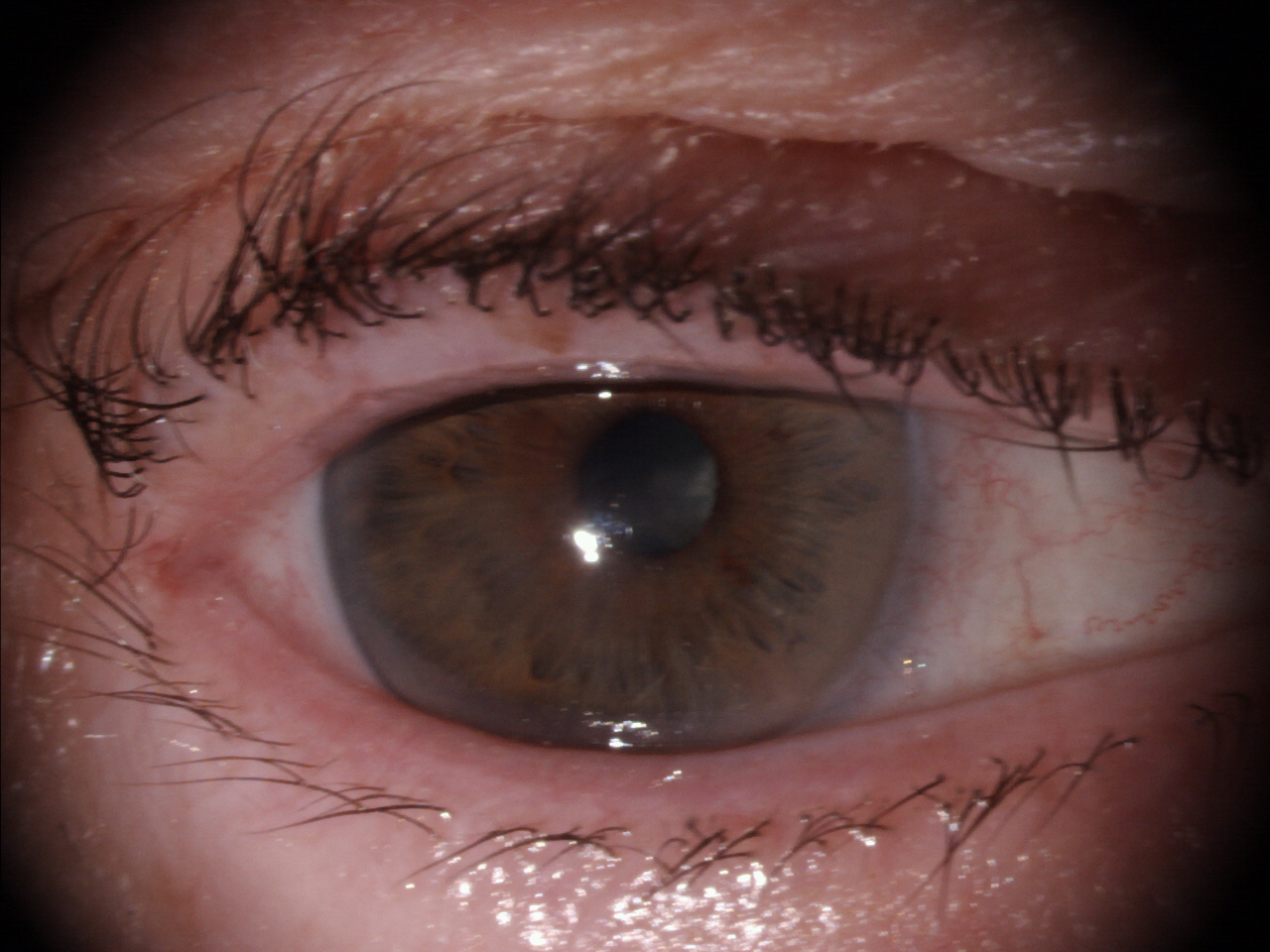

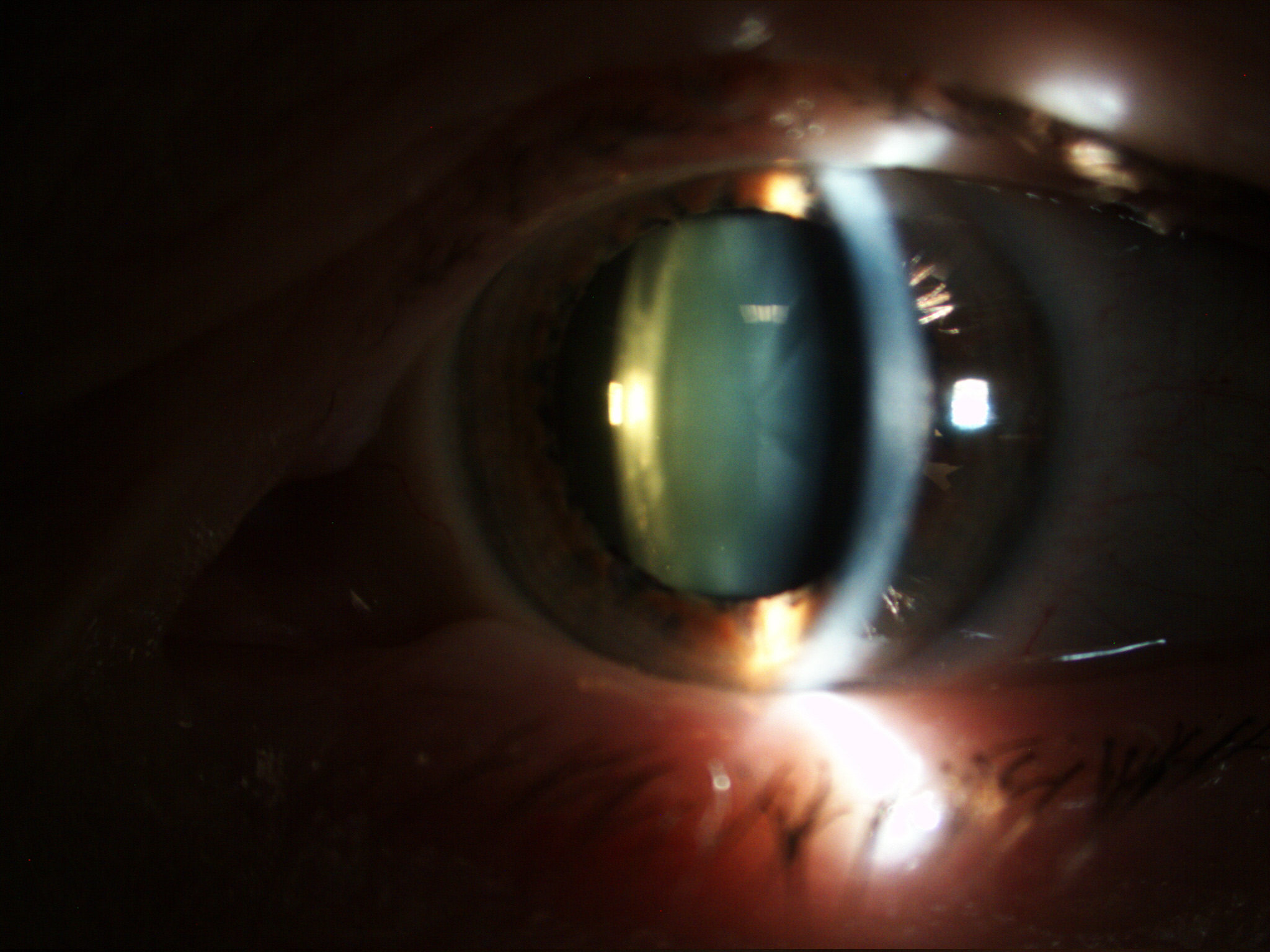

Figure 2: There are many expected changes with age that may influence the assessment of the visual system; (top) pupil miosis, (middle) lens brunescence and opacification, (bottom) ptosis

When examining elderly patients, optometrists should be aware of some expected age-related changes to the eye which may influence the way the test is undertaken and interpreted (figure 2). These include:

•Lens opacities

•Ptosis

•Fatigue during testing

•Reported glare or photophobia

•Diplopia

•Gritty or watery eyes

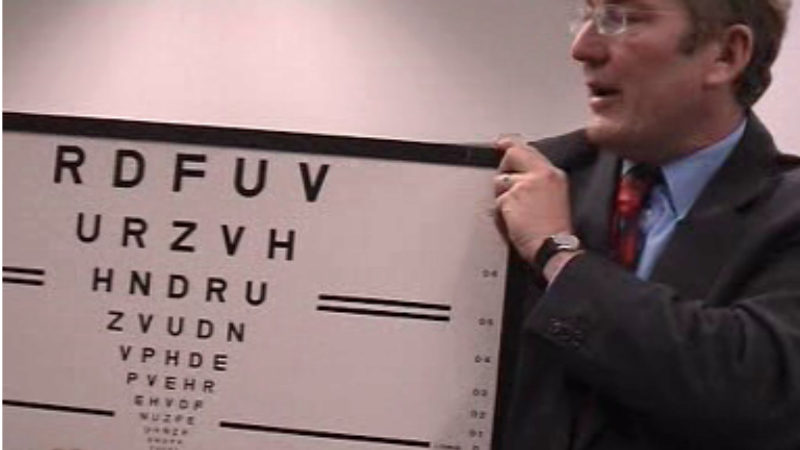

Figure 3: For those with visual impairment, a logMAR chart is preferred, and be prepared to alter working distance as required

Again, DOCET has produced online material that explains in detail how to adapt the routine eye examination to the needs of elderly patients. This material can be accessed by optometrists here: https://docet.info/course/view.php?id=140. The programme also offers examples of patient’s interviews.

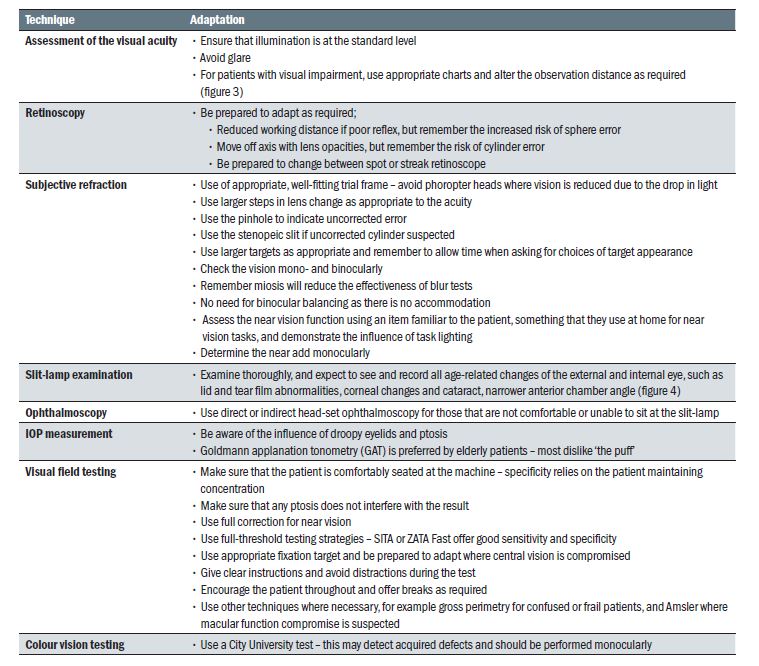

A detailed discussion of individual techniques is beyond the scope of this article, but table 1 offers a list of a few simple measures that could benefit our elderly patients during a routine ocular examination (adapted from https://docet.info/course/view.php?id=132)

More information about the above as well as about an appropriate refractive correction for elderly can be accessed at https://docet.info/course/view.php?id=132.

Table 1: Adaptation of the routine examination of the elderly

Measuring blood pressure in the optometric practice

A study performed in Saudi Arabia, showed that optometrists routinely measuring blood pressure (BP) were able to detect systemic hypertension in as many as one in eight previously undiagnosed adult patients.3 Indeed, eye care practitioners are ideally placed to implement BP screening, identifying undiagnosed hypertensive patients who may otherwise believe themselves to be healthy. Remember the condition is typically asymptomatic.

The ability of eye care practitioners to detect hypertension is further supported by a 2015 study, conducted in the United States, which showed that optometrists and ophthalmologists measuring BP identified more undiagnosed hypertensives than any other health professionals except for general practitioners and cardiologists.4 Nevertheless, despite these and other studies, there seems to be a general lack of both confidence and knowledge among UK eye care practitioners to be able to take and interpret a BP reading.5

In a more recent study performed in-house,6 it was found that despite patients being strongly in favour of optometrists measuring their BP as part of the eye exam, optometrists were neutral towards the idea, with a high degree of inter-participant variability in opinion. Moreover, the majority of the surveyed practitioners did not have access to BP monitoring equipment and felt they would not feel confident enough to take and interpret a BP measurement. That said, it should be emphasised that optometrists are uniquely placed to be able to compare a BP reading with the fundus appearance and are ideally set up in primary care community practice to participate in the BP screening for at risk groups. Many of those patients who might not attend their medical practice for a routine BP screening are likely to attend optometric practice regularly due to changes in their spectacle correction. If this practice is widely implemented, it might contribute to an overall reduction in the number of undiagnosed hypertensive patients with all its positive outcomes.

Lifestyle questionnaire and advice

Recently, various programmes such as the Dudley ‘Healthy Living Optician’ Scheme, have been introduced. In such schemes, the eye care practitioners offer advice on smoking, weight control, alcohol consumption, and may even undertake testing of glucose and cholesterol levels in the blood. In addition, optometrists are increasingly working together with both pharmacists and GPs to address general public health issues as part of NHS primary care teams. More details about the involvement of optometrists in public health matters have been discussed previously in this journal (see Optician 17.05.19).

Figure 4: Expect changes related to age, such as narrower anterior chamber angles

Comorbidity in elderly patients

Hearing impairment

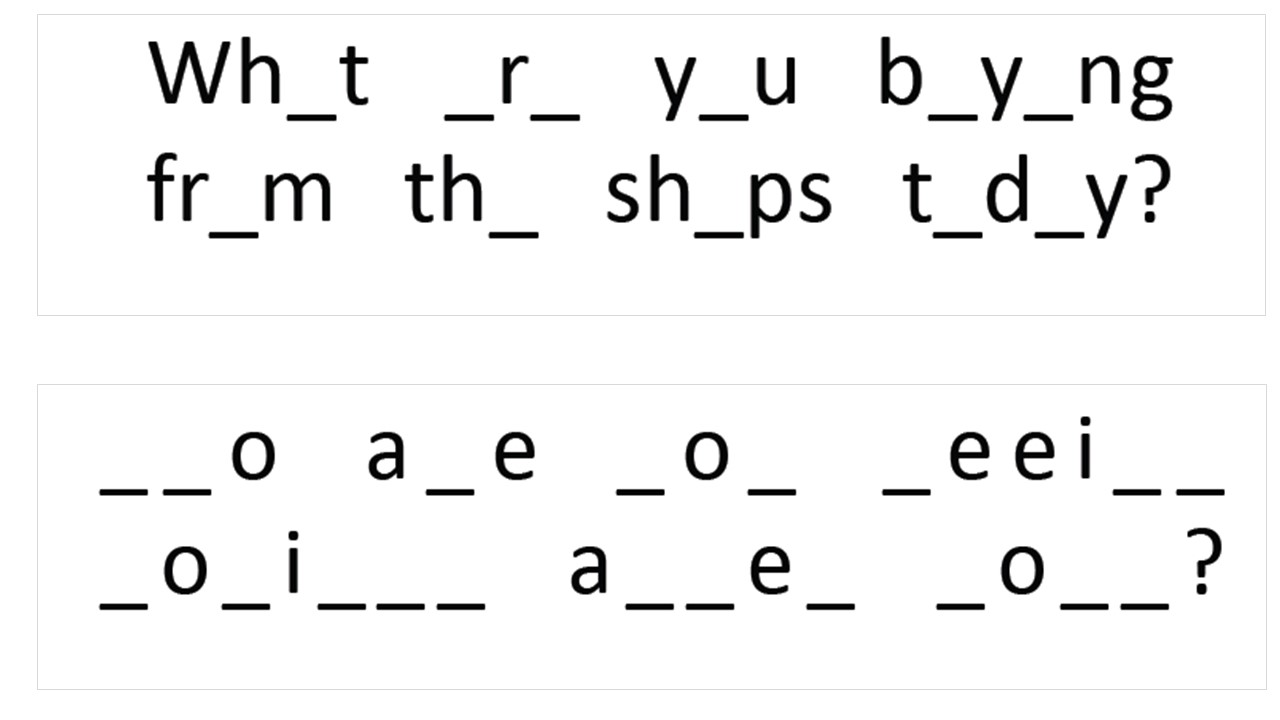

Hearing impairment is strongly associated with age, more so than visual impairment, and so it is very likely that our elderly patients will suffer both sensory impairments to varying degrees. As we age, higher pitched sounds are more difficult to discern from the background noise (figure 5) and, therefore, speaking loudly to our patients does not always help.7 Indeed, shouting distorts facial expression and makes interpretation more difficult.

Figure 5: High frequency loss impacts upon consonants. The lower construct shown here is harder to interpret

Some techniques that will help communicating with these patients are (adapted from 7):

- Reduce background noise (as a minimum, close the door)

- Move closer to the patient and position yourself at the patient’s eye level

- Establish asymmetry of hearing, and position accordingly

- Ensure good illumination, so the patient can see your face and read lips

- Use words that are easy to discern and pause between words that are harder to hear

- Emphasise key words

- Use gestures to complement your conversation

- Allow the patient time to respond

- Ask the patient to repeat key information to ensure they have understood

- Avoid sudden changes in the topic of the conversation

- Speak using your normal or a bit louder voice but do not shout

- Be patient and positive

- If possible, use specialist devices that help the patients with hearing impairment

Cognitive impairment

Memory loss or other type of cognitive problems are associate with normal or pathological ageing. More tips on communicating with and managing such patients were given elsewhere in this journal (see Optician 21.04.17).

Interprofessional communication

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), collaborative interprofessional practice occurs when ‘multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds provide comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings’.8

In all areas of healthcare, including optometry and ophthalmology, interprofessional communication is essential for improving the outcome for our patients, and this is especially important when caring for older adults who are likely to have multiple pathologies. Eye care professionals are at the frontline for detecting ocular and many systemic pathologies and need to ensure that the patients are referred appropriately. Similarly, visual impairment may first present to other specialists, such as those working in the field of neurology and endocrinology and, conversely, they will need to collaborate with ophthalmologists and optometrists. Unfortunately, this pathway route is all too often suboptimal and there is much room for improvement.9

As several specialities can be involved, good co-ordination of various care plans is required if one is to avoid clinical error, duplication of activity, failure to access relevant services, unwarranted lengthy hospitalisation, negative impact on the patients’ quality of life and increased health costs. Therefore, all health specialists and students should be educated to an appropriate level to understand the basic principles of interprofessional communication and care pathways.

WHO further states that ‘interprofessional education occurs when students from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes’; this is a ‘key step in moving health systems from fragmentation to a position of strength.’8

This is important because various teams might receive different levels of training and might have various exposures to dealing with such patients.10 At the moment, such training opportunities are scarce. And ‘…positive change demands a workforce that is culturally competent and diverse, trained in cross-disciplinary and integrative approaches to care, predisposed to both teamwork and leadership and inclined to lead quality improvement efforts.’11 Therefore, our role, as educators, should concentrate upon building such a workforce for the benefit of all our patients.

Dr Doina Gherghel is an academic ophthalmologist with special interest in inter-professional learning for optometrists. She also leads the new Geriatric Optometry module at Aston University.

For further information, email pgadmissions@aston.ac.uk.

References

- Rosenbloom AA: A proposed curriculum model for geriatric optometry, J Optom Educ, 1985; 11:22-24

- Besdine RW. Evaluation of the older adult. The Merk Manual. Available at; www.msdmanuals.com/en-gb/professional/geriatrics/approach-to-the-geriatric-patient/evaluation-of-the-older-adult. Accessed 14th of September 2019

- Al-Anazi S, Osuagwu U, Al-Mubarad T, et al. Effectiveness of in-office blood pressure measurement by eye care practitioners in early detection and management of hypertension. International Journal of Ophthalmology, 2015; 8: 612-21

- Handler J, Mohan Y, Kanter M, et al. Screening for High Blood Pressure in Adults During Ambulatory Nonprimary Care Visits: Opportunities to Improve Hypertension Recognition. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 2015; 17: 431-39

- Hurcomb P, Wolffsohn J. The management of systemic hypertension in optometric practice. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics, 2005; 25: 523-33

- McDonnell K, Gherghel D. Current opinion on optometric blood pressure measurement: a survey-based approach. 2019; Unpublished data.

- Norden LC. Factors that complicate the eye examination in the older adult. In Rosenbloom & Morgan’s Vision and Ageing, p163-177

- WHO (World Health Organization). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva: WHO; 2010

- Holley CD, Lee PP. Primary care provider views of the current referral-to-eye-care process: Focus group results. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2010; 51:1866–1872

- Balogun SA, Rose K, Thomas S, et al. Innovative interprofessional geriatric education for medical and nursing students: focus on transitions in care. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 2015; 108: 465–471

- Welp A, Woodbury RB, McCoy MA, et al, editors. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow. Chapter 7. Toward a High-Quality Clinical Eye and Vision Service Delivery System. National Academies Press (US); 2016