Cataract surgery is recognised as a safe procedure with minimal complications and good outcomes. However, no surgery is without risk and it is important to be mindful of this. If complications are not managed appropriately, the effect on vision can be extreme.

Early complications

Early complications are less commonly seen by community optometrists as patients tend to contact the hospital if they have any concerns during the early postoperative period. However, some patients do not have ready access to their hospital clinic and so their first course of action could be to seek the opinion of their own optometrist if they have any untoward symptoms.

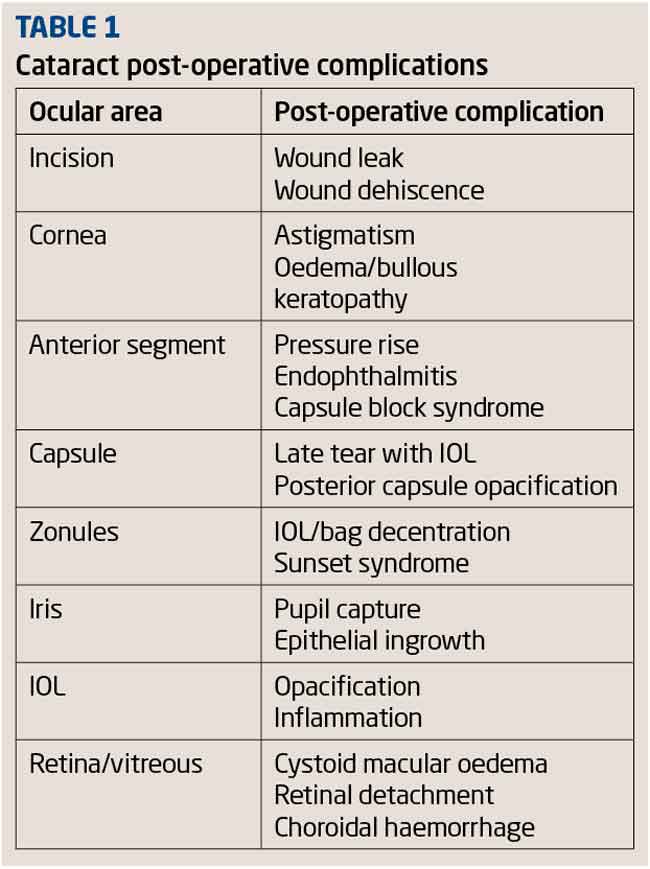

The information in Table 1 is taken from the Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ guidelines1 and lists the possible complications that can occur postoperatively. The complications that are potentially the most serious or are most likely to be seen by optometrists will be discussed below.

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis is potentially the most devastating of all postoperative complications. If it is not detected and treated effectively, it can ultimately lead to blindness and even enucleation. It is a severe intraocular inflammation resulting from infectious organisms entering the vitreous cavity during intraocular surgery. Fortunately, it is a rare complication with a reported incidence of between 0.08 to 0.68 per cent.2-5

A patient with endophthalmitis typically presents with a red, swollen eye that has become progressively painful and a worsening of the vision. Slit-lamp examination of the eye reveals eyelid oedema, conjunctival hyperaemia, limbal injection, corneal oedema and anterior chamber activity. Severe acute cases frequently have a hypopyon (Figure 1).

[CaptionComponent="2816"]

Indirect ophthalmoscopy following pupil dilation also shows inflammatory cells in the vitreous. As the condition progresses, the invading microorganisms stimulate a series of vascular changes that may ultimately lead to retinal inflammation and haemorrhaging. This can have a devastating effect on vision, with acuities of hand movements or less in the worst cases.

Emergency referral to an eye unit is imperative in such cases and the patient is likely to be treated with an intravitreal injection of multi-spectrum antibiotics in addition to topical antibiotics. Where the vision is severely compromised, a vitrectomy is also carried out. A microbiological investigation is always undertaken to identify the source of the infection.

Toxic anterior segment syndrome (TASS)

TASS typically presents within the first 24 hours after surgery and, unlike endophthalmitis, is not caused by an infective organism. The causes are thought to be to be linked to the preservatives in the intraoperative drugs or sterilisation chemicals used.6

Patients with this condition typically present with blurred vision and severe anterior segment inflammation. Although limbal to limbal corneal oedema and hypopyon are often present, the inflammation is usually confined to the anterior chamber. The condition responds well to topical steroids and generally resolves within six weeks. It can be difficult to differentially diagnose between this condition and infectious endophthalmitis and so it is best to refer the patient for urgent review by an ophthalmologist. Table 2 summarises the difference between the two conditions.

Anterior uveitis

Anterior uveitis is commonly seen in the short-term postoperative period despite the use of corticosteroids to dampen down the inflammatory response to surgical trauma. Immediately after surgery it is normal to see some corneal oedema, conjunctival hyperaemia and cells in the anterior chamber. By four weeks postoperatively there should be no cells present if recovery is normal. Figure 2 shows an eye which has not settled due to an iris filament that had become attached to the wound.

[CaptionComponent="2817"]

The attachment caused traction on the pupil and gave rise to uveitic signs and symptoms. Patients with dark irides are more likely to suffer from anterior chamber inflammation following phacoemulsification.7 These patients often have a greater amount of inflammation which often takes longer to resolve and is more likely to recur once steroid therapy has been stopped. They usually require more intensive steroid therapy and are followed up for a longer period of time. The risk of rebound uveitis is minimised by tapering the steroids slowly over a longer period of time.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) rise

Cataract surgery involves significant disruption in the anterior chamber and as a result glaucoma sufferers can encounter additional problems which can lead to visual loss. IOP spikes following cataract surgery are well documented in the literature and although healthy optic discs may tolerate this transient IOP rise, glaucomatous discs may not. One study documents deterioration in visual field defects in 9.7 per cent of its glaucomatous patients.8 It is therefore essential for the surgeon to manage the IOP of glaucomatous patients carefully when planning cataract surgery.

Steroid responders are another group of patients that need to be monitored more closely postoperatively. Studies have shown that the use of prescribed topical steroids over four to six weeks results in an increase in IOP of more than 16mmHg in 5 per cent of the population and an increase of between 6mmHg and 15mmHg in 30 per cent of the population.9 A moderate IOP rise for the duration of steroid use does not generally cause any problems but the patient should be reviewed two to three weeks post cessation of topical steroids to ensure that IOP returns to a normal level.

Corneal oedema

Corneal trauma during phacoemulsification can result in oedema, which usually resolves within two weeks. It is sometimes localised around the incision site (Figure 3) which tends to resolve within a couple of weeks.

[CaptionComponent="2818"]

But if the endothelium is compromised in any way either by age, physical trauma or dystrophy, oedema can take much longer to resolve. In cases of severe oedema, persistent folds in Descemet’s membrane (Figure 4) can be seen all over the cornea and loss in corneal clarity can result in hand movement vision.

[CaptionComponent="2819"]

There is little that can be prescribed to improve the speed of recovery and patient management is mainly observation and reassurance at this stage. Occasionally, sodium chloride drops are prescribed in an attempt to speed up recovery. This can take several months and in rare cases where corneal clarity does not return, a corneal transplant may be needed.

Retained lens material

Inadequate aspiration of the lens cortex during phacoemulsification is the commonest cause of retained lens material and is usually of the soft type, appearing as a white, fluffy mass in the anterior chamber. It can be seen in the early postoperative weeks and causes an inflammatory response within the eye, although patients may be asymptomatic if they are taking their normal postoperative anti-inflammatory medication. Small amounts of retained lens matter are usually left alone to reabsorb, but if there is a significant amount, surgical removal is essential as it can cause significant inflammation with raised IOP. The retained matter can also move over the pupillary area and obstruct the visual axis.

Figure 5 shows a more unusual case where a fragment of lens nucleus was found in the anterior chamber two months after surgery. The fragment had remained hidden behind the iris and avoided aspiration. At some point, perhaps when the patient was lying down, it had floated through the pupil space and then eventually dropped in to the anterior angle, where it remained lodged.

[CaptionComponent="2820"]

Later-onset complications

Pseudophakic cystoid macular oedema (CMO)

Also known as Irvine-Gass syndrome, CMO typically occurs 4-6 weeks after surgery, although occasionally it can occur months or years later. Incidence is up to 3 per cent10 and patients that have already had an episode of CMO with their first eye after surgery have a significantly increased risk (50 per cent) of the second eye also being affected. Ocular coherence tomography (OCT) or fluorescein angiography are usually used to confirm diagnosis, with OCT clearly showing the fluid-filled cysts (Figure 6).

[CaptionComponent="2821"]

However, fluorescein angiography is able to identify even very mild cases of CMO, as leaking perifoveal capillaries give rise to a flower petal-like appearance on imaging. It is known approximately one in five patients11 will have this ‘angiographic’ CMO which resolves spontaneously.

In optometric practice, the patient with ‘clinical’ CMO usually presents with a drop in vision, having had a good visual outcome initially. Reading vision is also disproportionately affected. There are rarely any other presenting symptoms although occasionally the patient may have a slightly pink eye and report some mild discomfort or photophobia. On examination, the anterior chamber may have some mild activity and the macular reflex may look a little dull, be absent or slightly irregular, according to the severity of the oedema. In more advanced cases it may be possible to see a honeycombed appearance with red-free light due to the presence of fluid-filled cysts. Where CMO is suspected, referral to an ophthalmologist for the patient to be reviewed within a few days is indicated. Mild cases of CMO cause transient vision loss and resolve without intervention within a few weeks, although persistent cases can take up to 12 months to resolve.

While the exact aetiology of CMO is uncertain, it is known that it does generally respond to anti-inflammatory therapy. Where treatment is indicated, the patient is usually given a topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory such as ketorolac (eg Acular) or nepafenac (eg Nevenac) to use for several weeks in conjunction with a steroid such as prednisolone (eg Pred-Forte). This is eventually tapered off as the symptoms resolve. If the CMO does not respond to topical therapy, an intra-vitreal injection may be required. In cases of severe oedema or where therapy is not started soon enough, the vision may be permanently compromised.

Post vitreous detachment (PVD) and retinal detachment (RD)

Many patients report an increase in floaters after cataract surgery, and sometimes it is simply because their ocular media is now clear enough for them to see pre-existing floaters. However, PVD and RD are more likely to occur in individuals that have undergone any form of intraocular surgery. PVD is common following cataract surgery and can occur at any time from early days postoperatively to months afterwards.

A patient presenting with an acute PVD should be re-examined periodically for up to six weeks if they are continuing to see flashes as this is a sign of vitreous traction which may cause a retinal tear. Figure 7 shows an OCT image of a PVD with traction over the macular area.

[CaptionComponent="2822"]

Figure 8 shows an eye that underwent cataract surgery two months earlier. Within the circle of the dilated brown iris, a white ring (fibrosed anterior lens capsule) can be seen. The vitreous detachment can be seen within the pupillary area which is more easily identified with eye movements.

[CaptionComponent="2823"]

Retinal detachment is a rare (1-2 per cent)12 but potentially serious complication of cataract surgery. The incidence is much lower with phacoemulsification than that found after intracapsular cataract extraction. Optometrists should look for Schafer’s sign in patients with suspicious symptoms. Shafer’s sign or tobacco dust is the presence of pigment in the anterior vitreous and is a sign that a retinal break may have occurred. The likelihood of a tear occurring is also far higher in patients with haemorrhagic PVDs compared with those without haemorrhage. Urgent referral for ophthalmologist opinion is indicated for any patient with symptoms or signs suggestive of a retinal tear as symptomatic retinal breaks often require same-day treatment.

Posterior capsular opacification (PCO)

PCO is the most common postoperative complication of cataract surgery with incidence of over 40 per cent within five years of cataract surgery.13 It is a multifactorial problem related to patient factors such as age, surgical factors and IOL design features. It is caused by residual lens epithelial cells which are left behind after extracapsular cataract surgery.

Residual lens epithelial cells around the edge of the anterior capsular surface undergo fibrosis and proliferation which can be considered to be a normal wound healing response following surgery. Where the anterior and posterior lens capsule surfaces meet, the cells can also migrate, causing a thickening and eventual clouding of the posterior capsule. Proliferation and fibrosis of these cells can create Elschnig’s pearls; droplet-like formations on the posterior capsule (Figure 9) or a fibrous sheet-like opacification.

[CaptionComponent="2824"]

Much research has been done over the years to minimise or delay PCO. In the developed world PCO is an inconvenience that can be treated in clinics but in poorer countries, where it is hard enough to provide cataract surgery to all that need it in the first place, PCO is yet another burden.

It is now the accepted consensus that a square-edge IOL optic is far more effective than a round one in preventing lens epithelial cells from migrating to the posterior capsule. The physical pressure of the IOL against the posterior capsule creates a barrier which can be made more effective if the posterior edge is a sharply defined edge as opposed to a rounded one. As long as there is a 360-degree overlap of the anterior capsule on the IOL optic, it creates a taut, cling-film like effect of the posterior capsule against the posterior surface of the IOL, thus minimising cell migration.

Patients whom have significant PCO tend to complain of gradual deterioration in vision and difficulty with glare. Such patients can be referred for ophthalmologist assessment and potential YAG laser capsulotomy. YAG capsulotomy is carried out by vaporising parts of the capsule in a cross pattern, the remnants of the central part of the lens capsule then break free to leave an opening over the pupillary area in the capsule (Figure 10).

[CaptionComponent="2825"]

These fragments are dispersed into the vitreous where the patient may be aware of them as floaters. They are not generally problematic and resolve in a few weeks. Patients usually see an improvement in their vision immediately and can return to their normal daily activities more or less straight away.

Although YAG capsulotomy is a simple procedure which takes only a few minutes, it is not without risk. The power used to laser the capsule varies according to the density of the opacification and the higher the power of the laser, the greater the risk of complications and pitting damage to the IOL (Figure 11).

[CaptionComponent="2826"]

As well as potentially causing a break in the retina, the shock waves generated by the laser pulse also stimulate the release of inflammatory mediators which may lead to cystoid macular oedema as well as an IOP rise during the first few hours following the procedure.

There is a well-documented pressure rise of up to 31 per cent in pseudophakic eyes that have undergone YAG capsulotomy. However, the IOP rise is rarely persistent and dissipates within 48 hours. Unfortunately, glaucoma patients are more susceptible to higher increases of up to 59 per cent and for a longer period of time leading to permanent vision loss.14-17 Therefore, optometrists should be more wary when measuring IOPs in glaucoma patients that have recently undergone YAG laser capsulotomy and refer for urgent assessment by a glaucoma specialist if IOPs appear to be significantly raised above the patient’s normal reading.

Less common complications

Lens dislocation

Lens dislocation is a rare complication with the patient complaining of blurred vision, glare and possibly diplopia. Even without dilation of the pupil it may be possible to see the decentration of the lens which is evident by the edge of the optic being within the undilated pupillary margin or, in severe cases, the haptic is visible. A well-placed IOL implant sits normally in the capsular bag but can become displaced over time by asymmetrical thickening or fibrosis of the lens capsule. This can cause high degrees of astigmatic error as well as higher-order aberrations and glare. This complication is also associated with trauma and previous vitreo-retinal surgery.18 Another cause of displacement can be due to weakening of the zonular fibres which support the lens capsule. Conditions such as pseudoexfoliation syndrome which weaken those fibres could cause the lens to dislocate.19-21 If the visual symptoms are disabling to the patient, referral is indicated for possible repositioning of the lens, or lens exchange surgery.

Ptosis

Ptosis is a very rare complication of cataract surgery and usually occurs several months after the event. Often a patient will notice ptosis after surgery because they are more aware of their eyes after undergoing a procedure. It is important to take a detailed ocular history as it is possible that ptosis may have been present prior to surgery but not noticed. This form of ptosis is usually transient and unilateral, affecting the eyelid of the eye that has undergone surgery, with the age of the patient and previous ocular and eyelid surgery making the patient more susceptible. It improves over the short term postoperative period without intervention and tends be caused by eyelid oedema or haematoma, foreign body reaction, ocular inflammation, and anaesthesia effects. Causes of persistent or chronic ptosis usually involve damage to the levator muscle due to toxic effects of anaesthesia, prolonged oedema, trauma from direct injection into the muscle or use of a lid speculum during surgery. Many cases resolve within 6-12 months and surgical intervention is not usually required.

Late-onset endophthalmitis

Most cases of endophthalmitis occur within a week of surgery although it can occur at any time. Late-onset endophthalmitis is usually due to low-grade microorganisms that manifest themselves weeks or months after surgery and often just after postoperative medications have been stopped. In most cases the causative agent is bacterial but fungal infections are also a possibility. Patients tend to present with a red eye and discharge and it is worth noting that the symptoms of late-onset endophthalmitis are usually less dramatic than acute cases. This is accompanied by cells in the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye. Emergency referral to hospital is indicated.

Late-onset endophthalmitis is a particular risk for glaucoma patients that have undergone a trabeculectomy procedure. This is because the surface of the globe is weakened and bacteria may enter the eye via the filtering bleb. This is a risk over the patient’s entire lifetime but poses an increased risk after cataract surgery with 23 per cent of patients developing a bleb-related complication that could lead to endophthalmitis within five years.22

Other considerations

Anisometropia

Patients can be left anisometropic if cataract surgery is only required in one eye, and the other eye is significantly ametropic. The preoperative discussion between surgeon and patient should include discussion of coping with spectacles after surgery. If the surgeon feels that the anisometropic difference is significant, the patient will be advised against having a plano target outcome. If the final refractive outcome leaves the patient with more than 3.00 dioptres of anisometropia and spectacle correction has been attempted but not tolerated, it is generally accepted that second eye surgery is justified.

Conclusion

The author hopes this series has provided a thorough overview of the cataract management process. Although this final part has looked at complications, it is worth bearing in mind that modern cataract surgery is generally a brief procedure with very few complications. For those patients that are unfortunate enough to suffer problems postoperatively, the effect on vision can be minimised by timely referral and remedial treatment or surgery.

Model answers

The correct answer is in bold text

1 Which of the following is associated with zonule damage?

A Endophthalmitis

B Astigmatism

C Sunset syndrome

D Epithelial ingrowth

2 Which of the following might suggest TASS as opposed to endophthalmitis?

A Onset 3 days post-op

B Posterior segment involvement

C Increased pain levels

D Responds well to steroid intervention

3 Why might sodium chloride drops be useful in managing corneal oedema?

A It has antimicrobial activity

B It is an antiseptic

C It establishes an osmotic gradient

D It acts as a lubricant

4 How long might one expect anterior chamber cells and flare to have subsided post-operatively?

A One day

B One week

C Four weeks

D None should be present so uveitis should be suspected

5 How many patients will show resolving angiographic CMO post-surgery?

A None

B 10 per cent

C 15 per cent

D 20 per cent

6 Which of thew following is NOT an associated complication of YAG capsulotomy?

A Transient IOP rise

B Anterior uveitis

C CMO

D IOL pits

Read more

References

1 Royal College of Ophthalmologists Cataract surgery guidelines 2004.

2 Sparrow JM. Monte–Carlo simulation of random clustering of endophthalmitis following cataract surgery. Eye, 2007; 21: 209–213.

3 Speaker MG, Milch FA, Shah MK, Eisner W, Kreiswirth BN. The role of external bacterial flora in the pathogenesis of acute postoperative endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology, 1991; 98: 639–649.

4 R E Stead, A Stuart, J Keller and S Subramaniam. Reducing the rate of cataract surgery cancellation due to blepharitis. Eye, advance online publication 3 July 2009; doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.171.

5 Mamalis N, Kearsley L, Brinton E. Post operative endophthalmitis. Curr Opin in Ophthalmol, 2002; 13(1): 14-18.

6 Choi JS, Shyn KH. Development of Toxic Anterior Segment Syndrome Immediately after Uneventful Phaco Surgery. Korean J Ophthalmol, 2008; 22(4): 220-7.

7 Onodera T, Gimbel HV, DeBroff BM. Effects of cycloplegia and iris pigmentation on postoperative intraocular inflammation. Ophthalmic Surg, 1993; 24(11): 746-52.

8 Savage JA, Thomas JV, Belcher CD 3rd, Simmons RJ. Extracapsular cataract extraction and posterior chamber intraocular lens implantation in glaucomatous eyes. Ophthalmology, 1985; 92(11):1506-16.

9 Jones R 3rd, Rhee DJ. Corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a brief review and update of the literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 2006 17(2): 163-7.

10 Sundelin K, Sjöstrand J. Posterior capsule opacification 5 years after extracapsular cataract extraction.J Cataract Refract Surg, 1999, 25(2):246-50.

11 Blackwell C, Hirst LW, Kinnas SJ. Neodymium-YAG capsulotomy and potential blindness. Am J Ophthalmol, 1984; 15;98(4):521-2.

12 Vine AK. Ocular hypertension following Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy: a potentially blinding complication. Ophthalmic Surg, 1984; 15(4):283-4.

13 Kurata F, Krupin T, Sinclair S, Karp L. Progressive glaucomatous visual field loss after neodymium-YAG laser capsulotomy. Am J Ophthalmol, 1984; 98(5):632-4.

14 Cullom RD Jr, Schwartz LW. The effect of apraclonidine on the intraocular pressure of glaucoma patients following Nd:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy. Ophthalmic Surg, 1993; 24(9):623-6.

15 Coscas G, Gaudric A. Natural course of nonaphakic cystoid macular edema. Surv Ophthalmol, 1984; 28 Suppl:471-84.

16 Jale Mentes, Tansu Erakgun, Filiz Afrashi, Gokhan Kerci. Incidence of Cystoid Macular Edema after Uncomplicated Phacoemulsification, 2003.

17 Neuhann IM, Neuhann TF, Heimann H, Schmickler S, Gerl RH, Foerster MH. Retinal detachment after phacoemulsification in high myopia: analysis of 2356 cases. J Cataract Refract Surg, 2008; 34(10):1644-57.

18 Davis D, Brubaker J, Espandar L, Stringham J, Crandall A, Werner L, Mamalis N. Late in-the-bag spontaneous intraocular lens dislocation: evaluation of 86 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology, 2009; 116(4):664-70.

19 Höhn S, Spraul CW, Buchwald HJ, Lang GK. Spontaneous dislocation of intraocular lens with capsule as a late complication of cataract surgery in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome – five case reports. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd, 2004 221; (4):273-6.

20 Lim MC, Doe EA, Vroman DT, Rosa RH Jr, Parrish RK 2nd. Late onset lens particle glaucoma as a consequence of spontaneous dislocation of an intraocular lens in pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol, 2001; 132(2):261-3.

21 Sandinha T, Weir C and Holding D. A delayed complication of cataract surgery in a patient with pseudoexfoliation: dislocation of the intraocular lens. Eye, 2003; 17, 272–273.

22 Ashkenazi I, Melamed S, Avni I, et al. Risk factors associated with late infection of filtering blebs and endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg, 1991; 22(10):570-4.

Michelle Hanratty is the senior optometrist at Optegra Birmingham and an examiner for the College of Optometrists