Intravitreal injection (IVI) of a therapeutic substance is the most common procedure performed in ophthalmology.1 The most effective way to treat wet AMD, and several other conditions affecting the macula, is to deposit a drug close to the site of the disease. At present, this usually means placing the drug within the posterior vitreous.

The medication is then held near the affected area to exert its effect for an extended period and so offer the maximum effect for the longest duration. IVI drugs have shorter half-lives and an increased clearance in vitrectomised eyes. For this reason, there may be an increased role in vitrectomised eyes for slow-release formulations where available.

Intravitreal injections of drugs, either in liquid or solid pellet form, are now commonplace and the sheer volume of treatments required has long outstripped the supply of medical professionals available to perform this procedure. Following groundbreaking work at Moorfields Hospital, it is now accepted that suitably trained and accredited nurses and optometrists can safely perform this task.

As with most of these advanced specialist procedures, it is usually necessary to attend an approved introductory course (in my case, I took part in a three-day session run by Moorfields), then have additional training under the supervision of a retinal consultant. After this, it is usual to perform around 100 supervised injections before being deemed safe to inject independently.

Some believe that you should hold the DipTpSP, (Diploma in Supplementary Prescribing), qualification if you are not being personally supervised by the retinal consultant at the time of the injection. This would definitely be the case if, as is commonplace, you are signing the prescription form for the drugs used.

IVI treatment in wet AMD

The three most commonly used anti-VEGF drugs given by IVI to treat neovascular ‘wet’ AMD, listed in increasing cost, are:

- Avastin (bevacizumab )

- Lucentis (ranibizumab)

- Eylea (aflibercept)

The cheapest, Avastin, is the most commonly used outside the NHS, though technically it is being used ‘off-label’ as its manufacturers have never applied for its use in the eye. In other countries, Avastin is the first choice due to the cost implications. Lucentis, made by the same company (Novartis), is licenced for ocular use but is many times more expensive. There are a multitude of studies that show Avastin is safe to use and equally effective to Lucentis.2

The newer compound, Eylea (Regeneron/Bayer), is more expensive still. However, it does have a longer effective half-life, requiring injections to be performed significantly less often. This can mean reduced cost in professional time and hospital resources as fewer IVI are required per year, and a corresponding reduction in the risk of endophthalmitis and other complications. Additionally, Eylea can also have deeper target tissue penetration, useful in treating choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) from polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV). However, not all cases of PCV respond to anti-VEGF treatment. Often these cases are instead treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Depending on consultant preference, usually a ‘treat and extend’ injection policy is adopted to determine the optimal

frequency of administration. Often this equates to an initial series of three, one-month injections, a review at four months at which time an injection is administered. If at the time of the four-month review, there has been no return of wet changes, the next review is set to six weeks. If at that time there is still no sign of return of wet AMD, an injection is made and the next review set to eight weeks. If there is a return to wet changes, the review period is shortened usually to the last period that showed consistent elimination of signs of exudation.

IVI treatment of other conditions

IVI steroids are used to treat the following conditions:

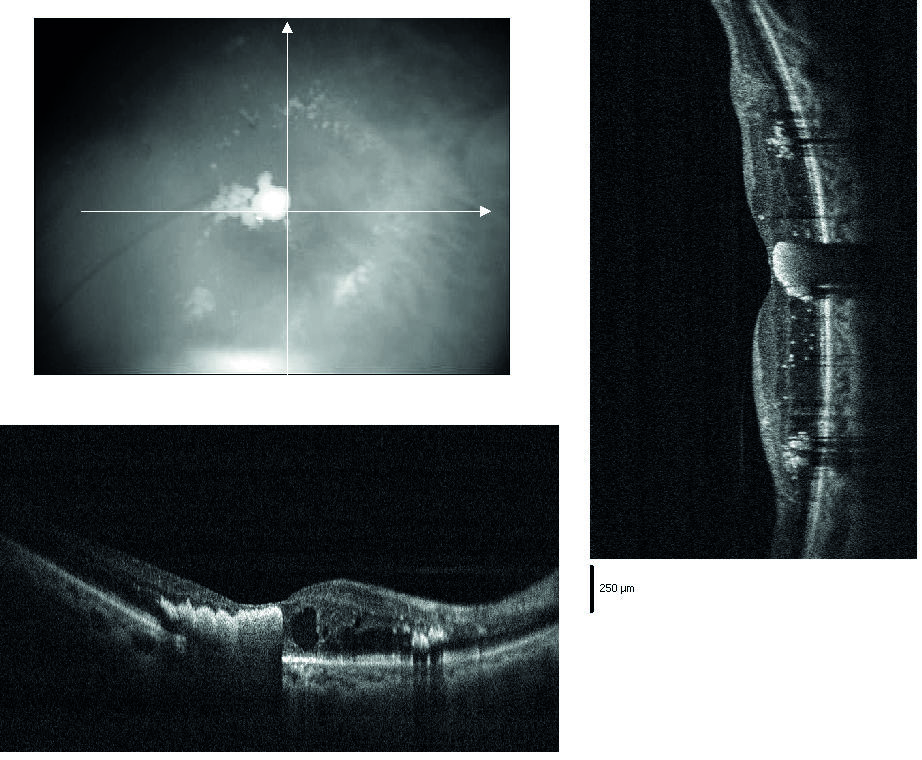

- Diabetic macular oedema (DMO, figure 1)

Figure 1: Diabetic macular oedema

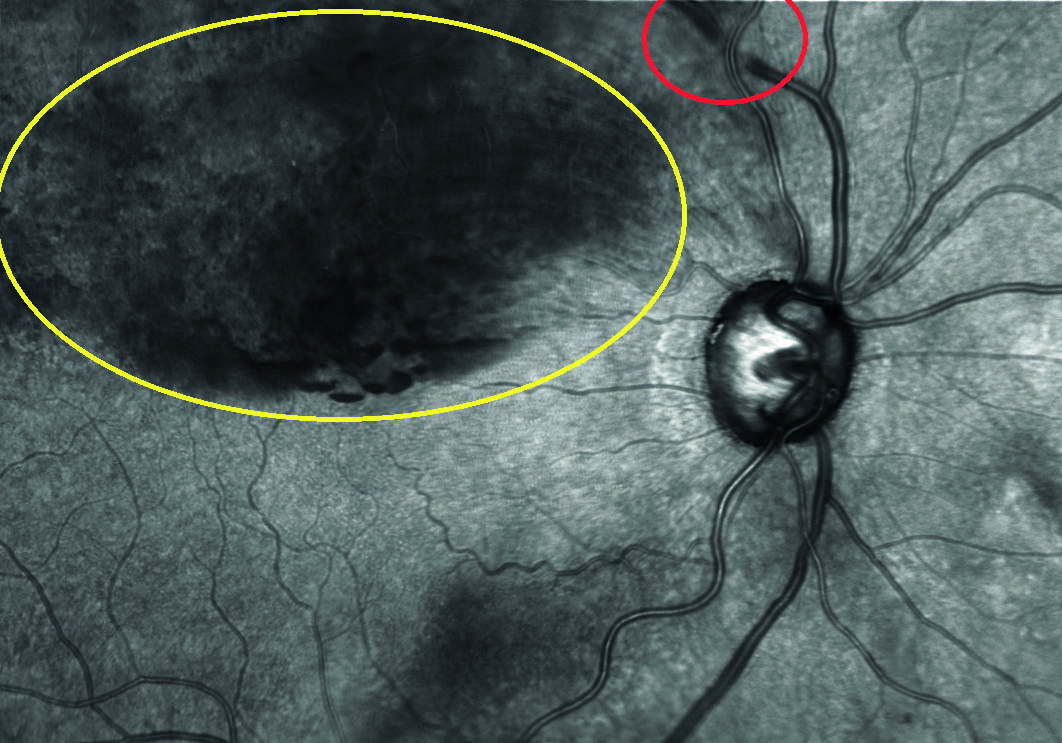

- Retinal vein occlusions (RVO, figure 2)

Figure 2: Superior branch retinal vein occlusion

Other conditions often amenable to IVI anti-VEGF treatment include:

- Myopic macular degeneration

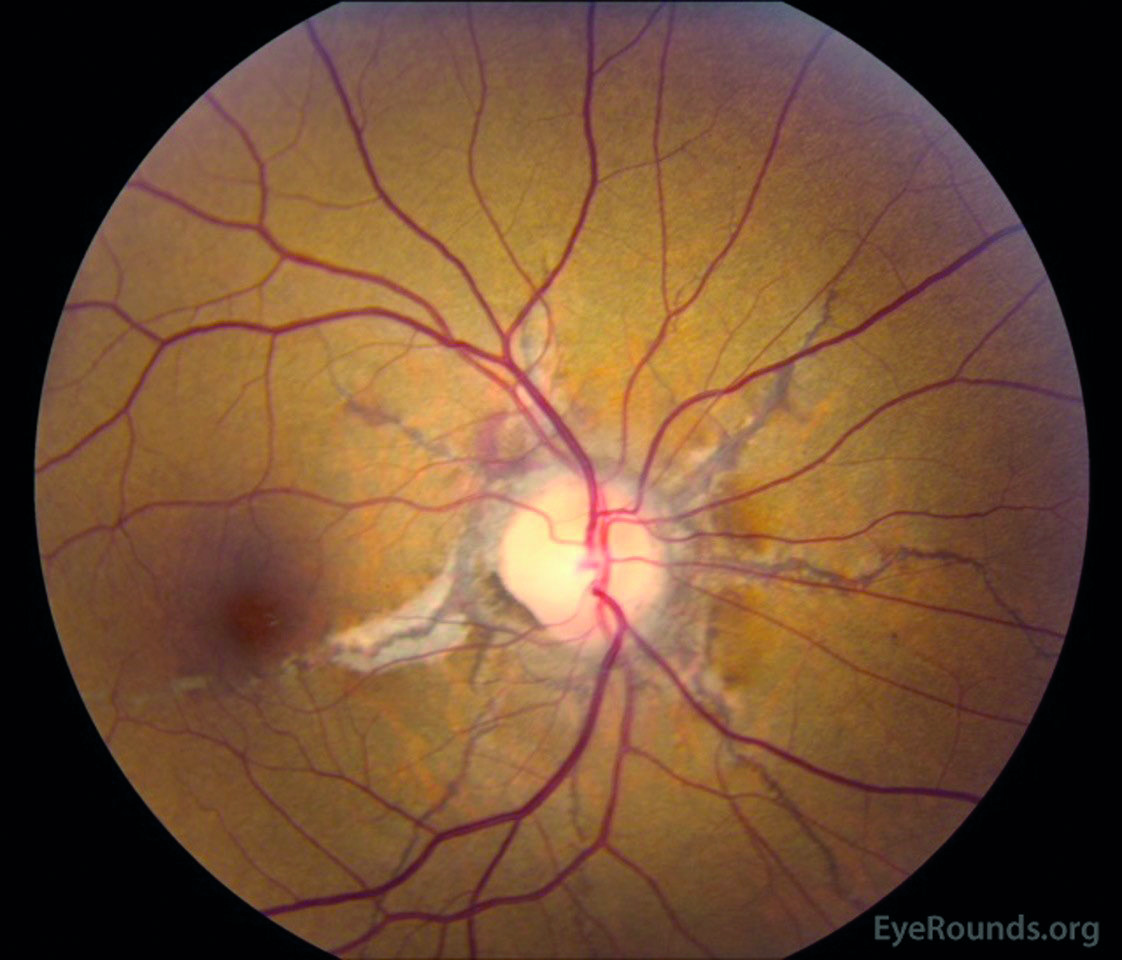

- Angioid streaks (figure 3)

Figure 3: Angioid streaks

- Certain forms of choroiditis

Topical steroids are not effective for significant or chronic macular oedema, though have a place in treating conditions such as cystoid macular oedema following cataract surgery. Systemic steroids can have significant side effects which outweigh the benefits in most cases of macular oedema. The main risks associated with IVI steroids, commonly used in diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and retinal vein occlusion (RVO) are glaucoma and cataract formation. Steroid pellets, such as Osurdex and Illuvian, carry the greatest risk of all due to their long retention time. Moderate pressure rises can be managed with ocular hypotensive drops.

Additional training is required for drugs such as steroids in suspension or pellet form. Steroids in liquid form (such as Kenalog) are normally in a suspension, and require a larger guage needle as the standard size can easily block with the suspended particles.

The injector devices used with pellets use very large bore needles. Subconjunctival lignocaine is the preferred anaesthetic due to its greater potency and the subconjunctival bleb makes it easier to ensure that the larger perforation at the injection site through the conjunctiva and through the sclera can made out of alignment and so make bacterial endophthalmitis less likely. I prefer this modality for Kenalog as well due to the slightly larger bore size needle used.

IVI – breakdown of the procedure

The room is first emptied and disinfected. The patient is consented and given written information. They are given a list of emergency contact phone numbers, including out of hours. The patient’s name, date of birth, allergies and eye to be injected is confirmed with the patient and the notes. No clothing is worn below the elbow and watches are removed, as are any elaborate rings.

The operating trolley and other surfaces are disinfected, the sterile intravitreal pack is opened onto it and the two dishes in this pack are filled with iodine and saline. Sterile gloves, a 13mm 30-guage needle and the IVI drug are hygienically dropped onto the sterile field. The intra-vitreal pack forms a sterile field on the trolley and normally contains cotton buds, a speculum, a towel to dry the hands, a limbal injection position marker and absorbant gauze squares.

A topical anaesthetic drop is instilled, (eg proxymetacaine), often in both eyes as this reduces the blink reflex, followed a minute later by a drop of tetracaine or lignocaine. Alternatively, the second anaesthetic can be applied with a soaked cotton bud.

Then disinfectant drops are instilled, usually iodine, but chlorhexidine can be substituted if the patient has a toxicity reaction to iodine. This is rinsed out with saline at the end of the procedure. A face mask is worn. It is important that iodine used on the ocular surface does not contain alcohol and is ideally preservative free (eg Minims).

Hands should be washed thoroughly using 7.5% iodine hand wash and sterile surgical gloves donned.

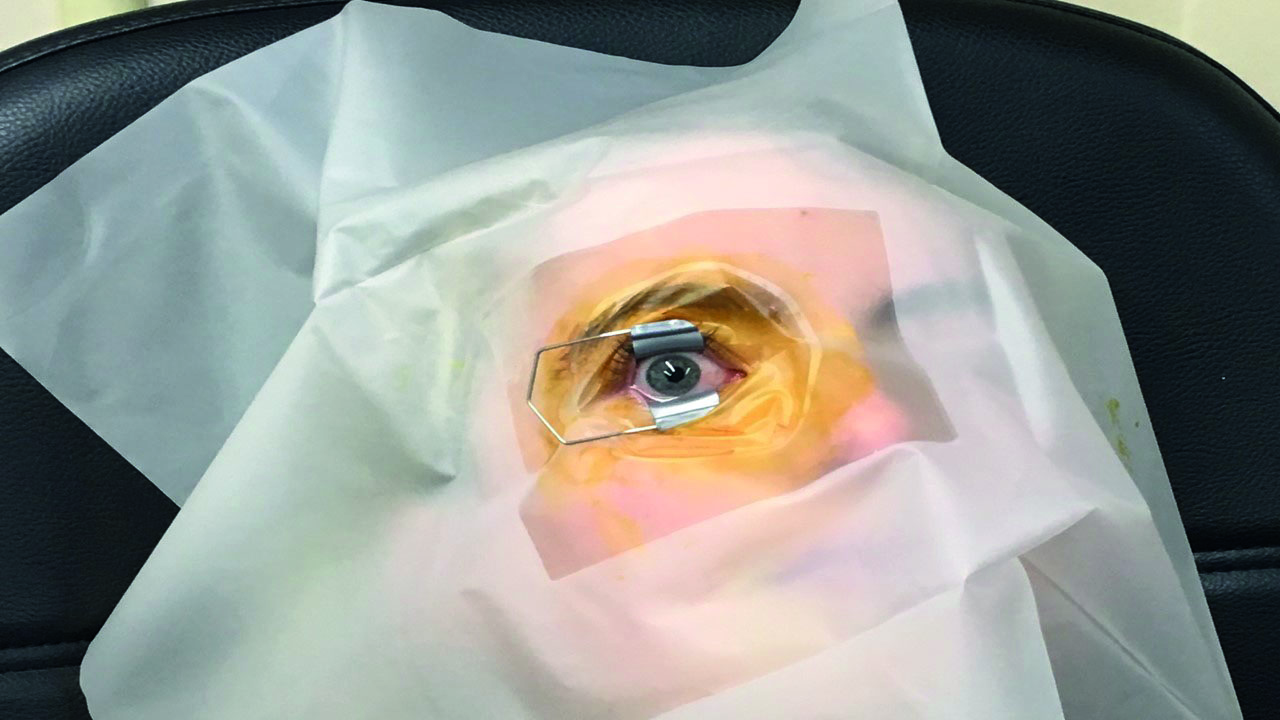

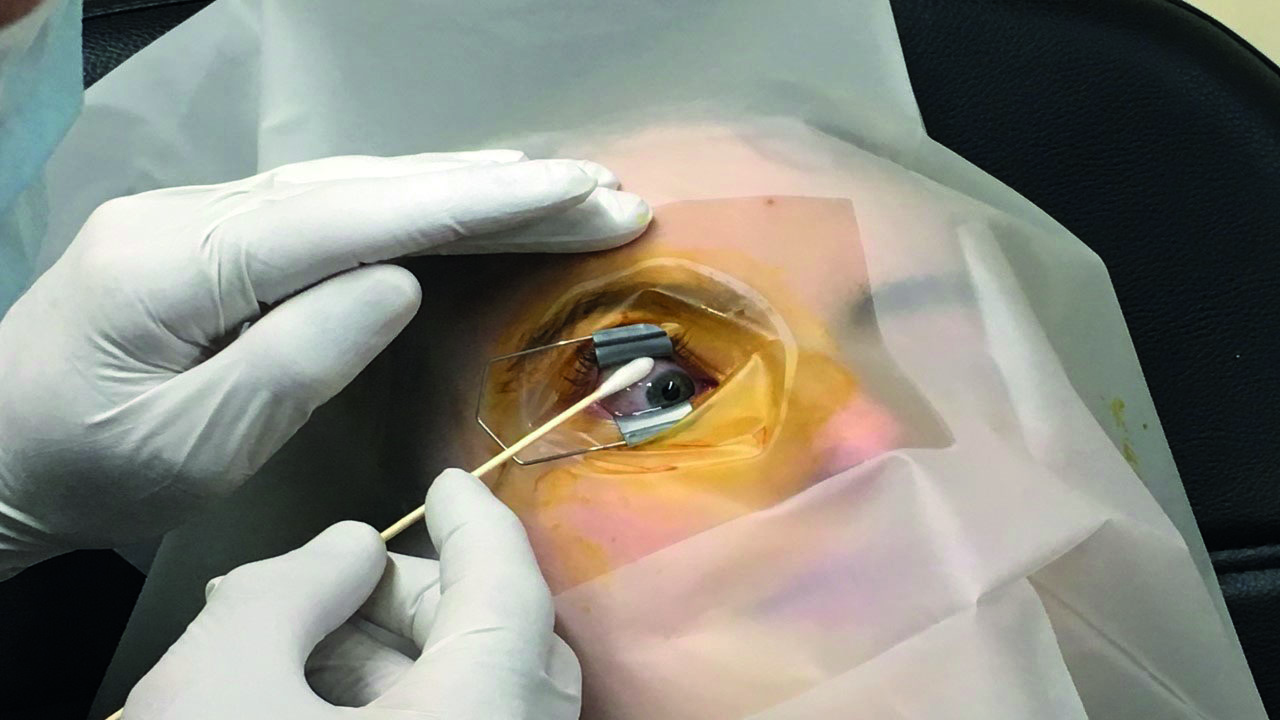

Eyelids, lashes and area surrounding the orbit are swabbed with 10% iodine (figure 4). If any significant sign of blepharitis is present, the procedure is aborted as the risk of endophthalmitis is too great. Patients should be encouraged to practice good lid hygiene before and between injections, so this problem does not occur. If a drape is deemed necessary it is applied at this stage.

Figure 4: Lid retraction after iodine swabbing of surrounding tissues

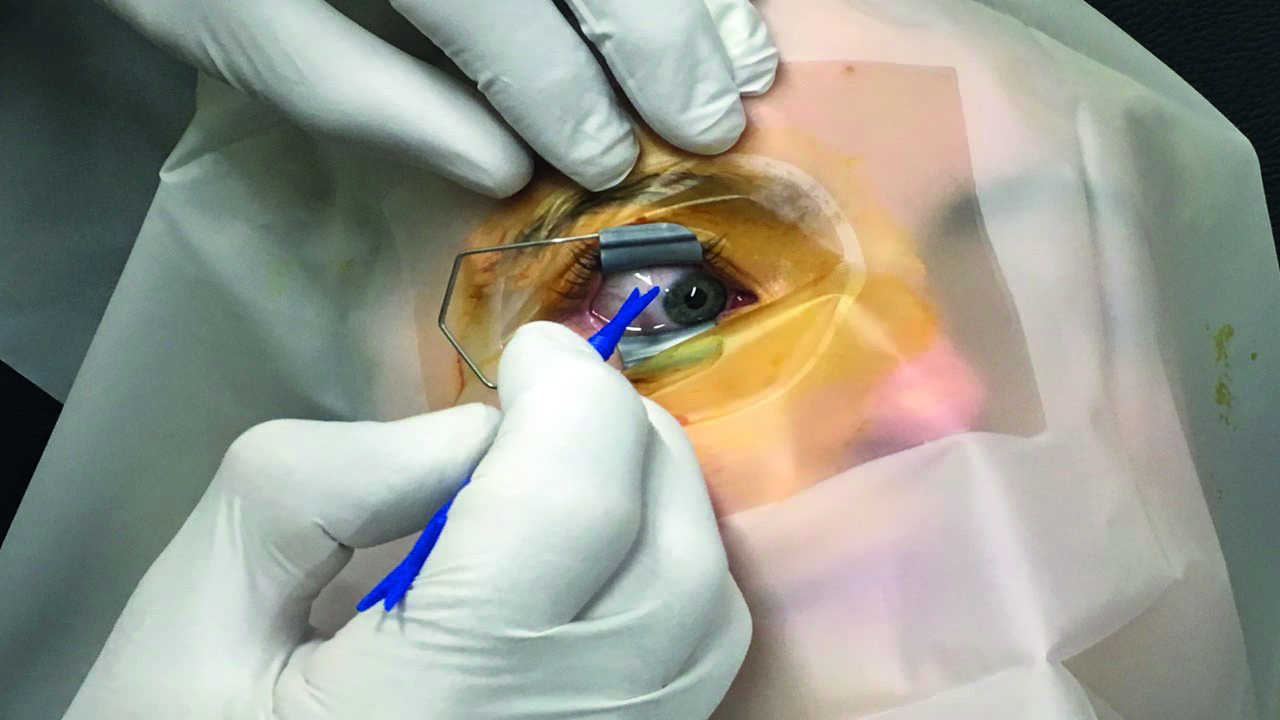

Additional topical anaesthetic (typically, tetracaine or lignocaine) is then applied to the injection site with a soaked cotton bud, or a sub-conjunctival injection of lignocaine is given (figure 5).

Figure 5: Additional topical anaesthesia application with a soaked cotton bud

Subconjunctival lignocaine can be used with or without adrenaline, which reduces the risk of sub-conjunctival haemorrhage due to its vasoconstrictive effect. While the anaesthetic effect is taking, the injection is prepared. Lucentis and Avastin come in a pre-prepared, loaded syringe, Eylea is usually drawn up from a vial. The excess drug and any bubbles are expelled from the syringe.

A lid speculum/retractor is usually inserted at this point. Care must be taken not to abrade the cornea when the speculum is inserted. Once the lids are retracted, the rest of the procedure needs to happen in a timely fashion to prevent corneal desiccation.

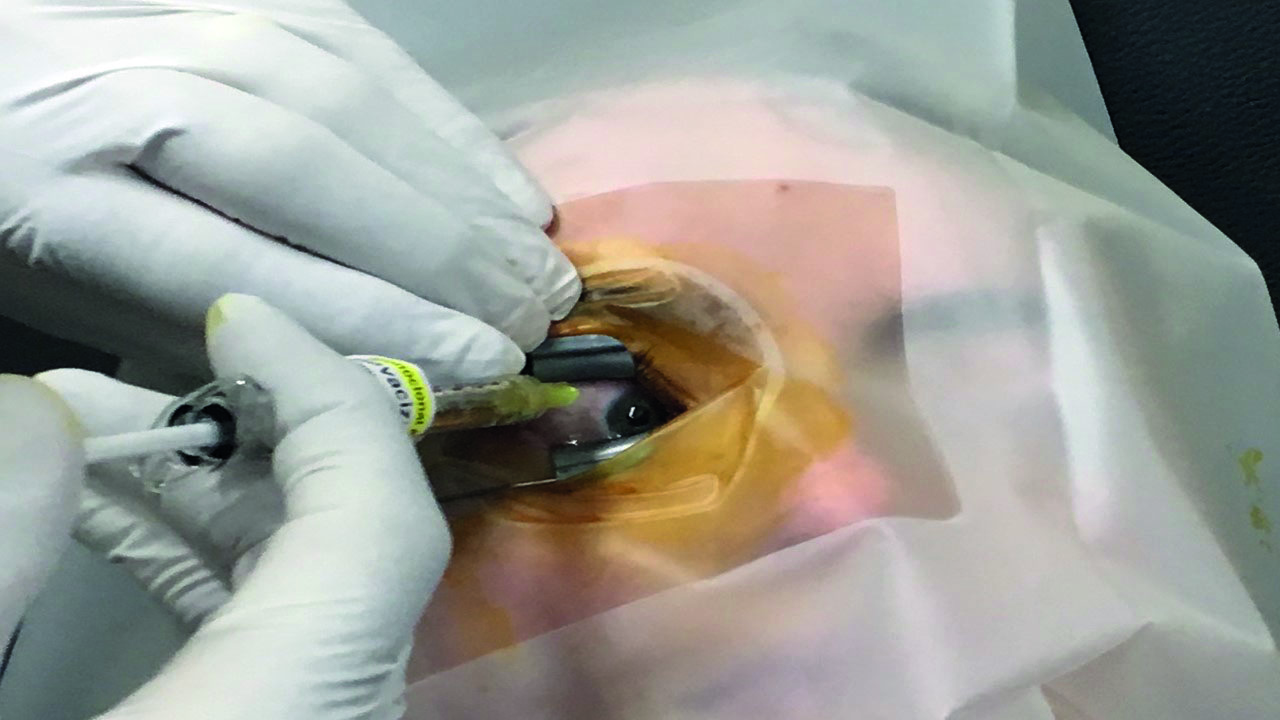

The injection site is marked with a pointed distance marker (figure 6). This marks the distance from the limbus to where the needle is inserted. Some feel that this should be slightly greater in a phakic eye to reduce the chance of catching the crystalline lens with the needle and causing a traumatic cataract. Placing the injection in this way also reduces the risk of retinal detachment, as does the use of small diameter sharp needles.

Figure 6: The injection site is marked with a pointed distance marker

The needle is inserted smoothly at a relatively swift pace, the plunger is depressed and the syringe is withdrawn again smoothly along the axis of the needle, with no lateral force being exerted, all the time encouraging the patient not to move their eyes at all during the procedure (figure 7). Giving the patient a target to fixate on, often helps.

Figure 7: The needle should be inserted smoothly at a relatively swift pace

Generally, just as the needle is withdrawn, a dry sterile cotton bud is pressed over the injection site, the aim being to provide a tamponade to stop the egress of vitreous humour, which could ‘wick’ bacteria into the vitreous. Some advocate using an iodine-soaked cotton bud for this purpose. This however, may encourage iodine ingress and a resulting intraocular inflammation/uveitis which can be serious. Opinion is divided on whether such a tamponade affects the incidence of endophthalmitis.

The main thing is that the needle goes nowhere near the back of the lens on insertion, but is aimed towards the optic disc. As the needle is only 13mm long there is no danger of actually hitting the optic disc. Some clinics use a disposable lid-retaining needle guide, called IntraVitrea, to ensure the needle passes into the eye at the right angle and the correct distance from the limbus. The main disadvantages of this system are cost and the fact that it is quite possible to blunt the needle, resulting in a more uncomfortable injection.

At this point I would irrigate the eye with saline and then check the patient can count fingers (CF) at 1m. If someone with at least moderate macular degeneration or oedema can no longer CF, this is most likely indicative of a central retinal artery occlusion due to severely raised IOP – an ocular emergency usually requiring a paracentesis if ocular massage fails to lower the IOP. It should be borne in mind that some patients have less than CF vision before injection, so more emphasis should be placed on their post-IVI IOP. I measure the IOP of every patient, pre- and post-injection.

I give the patient an artificial tear solution (such as Meibo-Tears) to use four times daily for four days and then as required, (more frequently with dry eye patients). I then confirm the booking of the next appointment at the appropriate interval.

Complications and adverse reactions

During the informed consent process, the patient should be made aware of all of the possible complications. Patients are also reassured that mild foreign body sensation/grittiness is normal following an injection and may not start for several hours after the anaesthetic begins to wear off. If patients are reassured regarding likely outcomes (gritty eyes, medication ‘floaters’, foreign body sensation, and subconjunctival haemorrhage), anxiety is alleviated and the number of emergency follow-up visits is reduced. Despite necessary precautions being taken, complications do occur.

Corneal staining/ocular surface disease

Iodine can cause a toxicity reaction in the corneal epithelium. Most people get a slightly gritty eye after IVI, especially those with pre-existing dry eye. It is recommended that the dry eye status of IVI patients is evaluated before and during a course of treatment and prophylactic use of artificial tears implemented.3 We give our patients a new bottle of Meibo-Tears dry eye drops four times daily for four days. If they have had previously a gritty eye following the IVI and/or poor tears, we get them to instil them morning and night for the period between injections.

Additionally, corneal erosions can occur with excessive instillation of anaesthetic drops, especially tetracaine (figure 8). Personally, I prefer to use fewer drops and apply more anaesthetic with a soaked cotton bud as this results in less anaesthetic contact with the cornea.

Figure 8: Corneal erosion

Corneal abrasion can occur from careless insertion/removal of the speculum. The use of the speculum is commonplace, though there is an argument that doing so can express less than sterile meibomian contents into the tear film, posing a theoretical increased endophthalmitis risk. With patients that know me and are relaxed about the procedure, I often do not use a speculum, rather digitally restraining the lids, which is generally much less stressful for the patient. Some, however, do not trust themselves not to go into blepharospasm and feel reassured to have the speculum in place. The important thing to remember, whether a speculum is used or not, is that nothing must touch the injection needle during the procedure, or bacteria could enter the eye with devastating consequences.

Floaters

Patients receiving IVI medications frequently report seeing floaters after a procedure, especially with steroid injections as these can be more particulate in nature. Some patients benefit from sleeping with the head of the bed elevated for one or two days post-treatment to allow ‘the bubble’ of medication or air to settle out away from the visual axis. These ‘bubble floaters’ are harmless and patients can be reassured, but caution must be observed if they occur in association with flashing lights or peripheral field loss, which could indicate a retinal tear or retinal detachment.

Subconjunctival haemorrhage

Subconjunctival haemorrhage (figure 9, SCH), caused by nicking a conjunctival blood vessel with the needle, is usually insignificant and haemorrhaging usually stops with digital pressure after a few minutes. It is much more likely with patients on blood thinning medication. Often, once the sub-conjunctival space has absorbed a reasonable amount of blood, this acts as a tamponade, arresting the further flow of blood. It is tempting to try to drain the excess blood in these cases. If the patient is on anti-coagulants, it is best not do this, as the tamponade effect is then lost and excessive bleeding may occur, often for a prolonged period. Using lignocaine with adrenaline as a topical anaesthetic in eyes with a vascularised bulbar conjunctiva or patients on anti-coagulants, can reduce the incidence of IVI induced SCH.

Figure 9: Subconjunctival haemorrhage

Glaucoma and IOP spikes

Following IVI, a transient rise in IOP is normal and usually returns to baseline within five minutes without intervention or ocular massage. This is more likely if a bubble is injected or if the patient has poor aqueous outflow. In patients who develop dangerously high IOP spikes, topical IOP-reducing agents, oral medication, and possibly paracentesis/anterior chamber tap can be used as means to reduce IOP and thereby prevent optic nerve damage and possibly central retinal artery occlusion.

In patients who have pre-existing primary open-angle glaucoma, especially those with significant visual field loss, IOP spikes after IVI need controlling to prevent further glaucomatous damage occurring. This often means pre-treating with Iopidine or Diamox before IVI to ensure that the IOP does not get to a dangerous level once the extra fluid is injected into the eye. In patients who have had pressure spikes on previous occasions, I would also pre-treat with Iopidine to be on the safe side.

We should not avoid IVI in patients with existing glaucoma, even with steroids because the visual loss in untreated macular disease may be irreversible and could compound the vision loss due to the glaucoma. In certain cases, routine prophylactic paracentesis prior to IVI, may be considered an option in patients with advanced glaucomatous disease. In rubeotic glaucoma, an IVI is usually an essential part of the treatment to reduce the retinal VEGF trigger which causes the angle and iris the angle vascularisation. These patients often have markedly reduced outflow capability and can get really high IOP spikes after IVI.

Paracentesis

The one case of paracentesis I have had to perform was on a patient with this condition, whose IOP went up to 85mmHg and his vision gradually blacked out as his central artery occluded. Fortunately, when I managed to drain some fluid from his anterior chamber, his IOP dropped to 35mmHg and his vision returned.

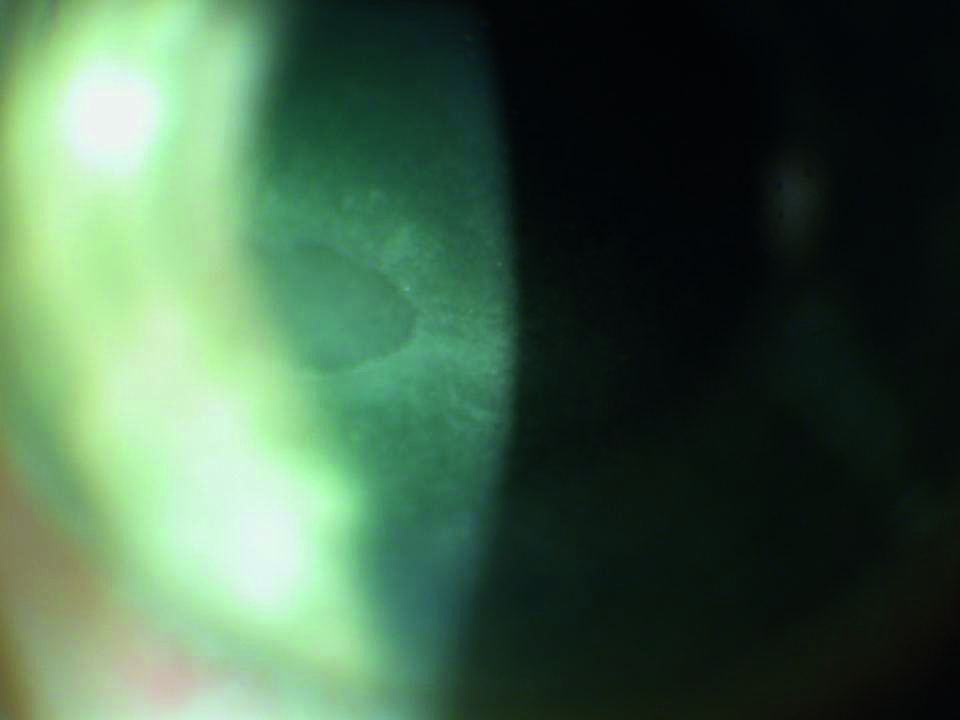

In paracentesis, an open (or closed, depending on individual preference) 27-gauge needle syringe is inserted through the peripheral cornea about 1mm anterior to the limbus, parallel to the plane of the iris, until two to three drips of aqueous leave the anterior chamber into the syringe body (figure 10).

Figure 10: In paracentesis, a 27-gauge needle syringe is inserted through the peripheral cornea about 1mm anterior to the limbus

It is important to avoid the iris to prevent hyphaema formation, the crystalline lens to avoid cataract and the corneal epithelium to avoid decompensation. It is particularly tricky in cases of shallow anterior chambers and angle and iris rubeosis (as in this case). Shallow anterior chambers make placing the needle more unforgiving and rubeosis massively increases the chance of an anterior chamber bleed. Because the peripheral cornea, especially with an oblique approach, is thicker and extremely tough, it is often necessary to fixate the globe with forceps, so that enough pressure can be exerted on the needle to penetrate into the anterior chamber.

Cataract

There are two ways that cataracts can result from IVI treatment: Firstly, it can be an acute traumatic complication usually due to poor technique where the needle catches the posterior aspect of the lens. Secondly, for patients receiving steroid IVI, cataract can be more of a long-term chronic complication, caused by the steroids themselves. The mechanism of the cataract formation is unknown. Most types of cataract can occur, but posterior subcapsular cataracts are the most prevalent.

Endophthalmitis/infection

The most worrying complication of IVI is endophthalmitis, which is associated with a poor visual prognosis even with prompt diagnosis and treatment and visual loss is common. Treatment usually involves intravitreal antibiotics or vitrectomy.4

The incidence of endophthalmitis varies amongst studies, but figures of 1 in 5000+ are achieved locally. A systematic review of 20 large retrospective studies had an estimated endophthalmitis rate of 0.028% (1 in 3,544 injections).5

Pre- or post-injection prophylactic, topical antibiotics have not been shown to be effective, and run the risk of creating a ‘super-bug’ resistant to treatment in the future.

The prevalence of streptococcal endophthalmitis infections after intravitreal injection is suggestive that aerosolization is likely to be a source of infective agents. This risk can be minimized by wearing a face mask. If there is any suggestion that the patient might start wheezing or talking during the procedure, I get them to wear a face mask as well.

Bilateral IVI should be performed as two separate procedures, using drugs from different batches wherever possible, especially when using compounded drugs. With fastidious eye lid and adnexa disinfection and the regular use of face masks and general good hygiene, hopefully the incidence of endophthalmitis will continue to drop over the future.

Retinal detachment

A common mechanism for the development of a retinal detachment is vitreoretinal traction, usually in the far periphery near the ora serrata, producing a retinal tear with subsequent entry of liquefied vitreous into the subretinal space. The use of small-gauge needles reduces the chance of vitreous traction at the vitreous base. Retinal detachment can also occur if the peripheral retina is perforated by the needle during IVI. This is why careful measurement of the injection site location is important. A patient complaining of floaters, photopsia or peripheral vision loss should receive prompt evaluation and treatment if required.

Systemic toxicity (anti-VEGF)

The question here is, does having anti-VEGF injections increase the risks of having serious adverse events such as systemic hypertension and arterial thromboembolic events (ATEs)? Those patients taking systemic anti-VEGF do have an increased incidence of ATE. Patients who have wet AMD are in a group that are likely in many cases to get more ATE compared to age-matched normals. Despite this, studies have not shown a definite association between having anti-VEGF injections and an increased risk of ATE.

Optometrist Involvement

Currently the biggest IVI treatment backlog is in wet AMD. This is a chronic eye disorder (which can develop very quickly) and ideally should be treated within two weeks of diagnosis. Most hospital eye departments are failing to meet this target owing to the intense workload they are already under. This is despite the fact that specially trained eye department nurses are able to perform the procedure. If more optometrists were involved, we could come closer to achieving the treatment guideline. Optometrists have both the manual dexterity and attention to detail required. Moreover, they have in depth knowledge of the eye structure and health. Performing IVI procedures seems like a natural progression of a therapeutic optometrist’s skill base.

Clinician qualities required are a steady hand, patient empathy and to be calm under pressure. Then, to become competent at the technique, you need to jump through a few hoops. Usually, this means completing an approved introductory course, such as the one I took at Moorfields Eye Hospital in 2014. I then talked to local ophthalmologists about becoming involved in their IVI scheme, explaining that I had both supplementary and independent prescribing qualifications. In the initial stages, I gave my time free which removed the cost barrier to acceptance. I then performed 100 IVI under supervision, before being able to conduct clinics in my own right. I worked one morning a week and provided holiday cover as required. I have now performed well over 1,000 injection procedures.

By performing IVI you can really contribute to the nation’s eye health, enabling more patients to be treated early enough to make a difference ensuring they achieve a better visual outcome. There is also no doubt that our involvement in these blindness preventing procedures massively improves our standing as healthcare practitioners in our patients’ eyes. In a way it gives me a similar buzz to when providing eye care in third world countries on a voluntary basis, you finish the day feeling you have really helped some people in a really meaningful way. This is what optometry is all about.

Andrew Matheson is a Specialist Therapeutic Optometrist involved in medical retina treatments, glaucoma management and providing hospital laser surgery services.

References

- Keenan TDL, Wotton CJ, Goldacre MJ (2012) Trends over time and geographical variation in rates of intravitreal injections in England. Br J Ophthalmol 96(3):413.

- Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, Downes SM, Lotery AJ, Culliford LA, et al. Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 382: 1258-67

- Laude A., Lim J et al. The effect of intravitreal injections on dry eye, and proposed management strategies. Clinical Ophthalmology, 2017, 11:1491-1497

- Merani R and Hunyor AP. Endophthalmitis following intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injection: a comprehensive review. Int J Retina Vitreous. 2015 Jul 21;1:9

- Lau P et al.. Current Evidence for the Prevention of Endophthalmitis in Anti-VEGF Intravitreal Injections. Journal of Ophthalmology, Volume 2018, Article ID 8567912