The General Optical Council’s first required CET competency unit for the continued registration of optometrists, dispensing opticians and contact lens opticians is communication.1 Specifically: ‘the ability to communicate effectively with the patient and any other appropriate person involved in the care of the patient, with English being the primary language of communication.’ The competency is then broken down into two elements:

- The ability to communicate effectively with a diverse group of patients with a range of optometric conditions and needs, and

- The ability to impart information in a manner which is appropriate to the recipient.

For some, good communication skills come naturally, for others it is a skill that requires learning and development. An analysis of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) of optometry students showed a dominant profile categorised as ‘Introvert, Sensing, Feeling & Judging’ (ISFJ).2 While this personality type has admirable qualities in terms of being warm and caring, its downside is that those with an ISFJ profile may struggle to communicate with those who do not express themselves well. In addition, the desire to be warm and supportive can, at times, be contradictory to the need to be directive and assertive in some situations. Communication errors were cited as the most common category reported in a pro-active pilot study looking at errors in optometric practice.3 In many of the cases, the errors were related to poor communication between staff members, often specifically that between professional and non-registered staff, highlighting the importance of staff training. A lack of feedback from other professionals, typically after referral to ophthalmologists, was also cited as a ‘communication error’.

This series of articles will cover all aspects of communication in optometric practice, as defined by the GOC competencies. In this first part we will look at the importance of communication and the impact that good and bad communication has on patient outcomes and business results. In future parts we will consider verbal, non-verbal and written communication and touch on the way that communication styles need to change with changing media habits.

Patient satisfaction

A basic truth concerning patient satisfaction is that unhappy patients tell many more people about their experience than happy ones do. The usual statistic from customer satisfaction research is that a happy customer will tell three to five people about their experience, whereas an unhappy customer will tell 10 to 15 others. In a world of social media, these statistics are probably understated. If the average Twitter user has 200 followers, then one well-placed complaint has the potential for huge damage.

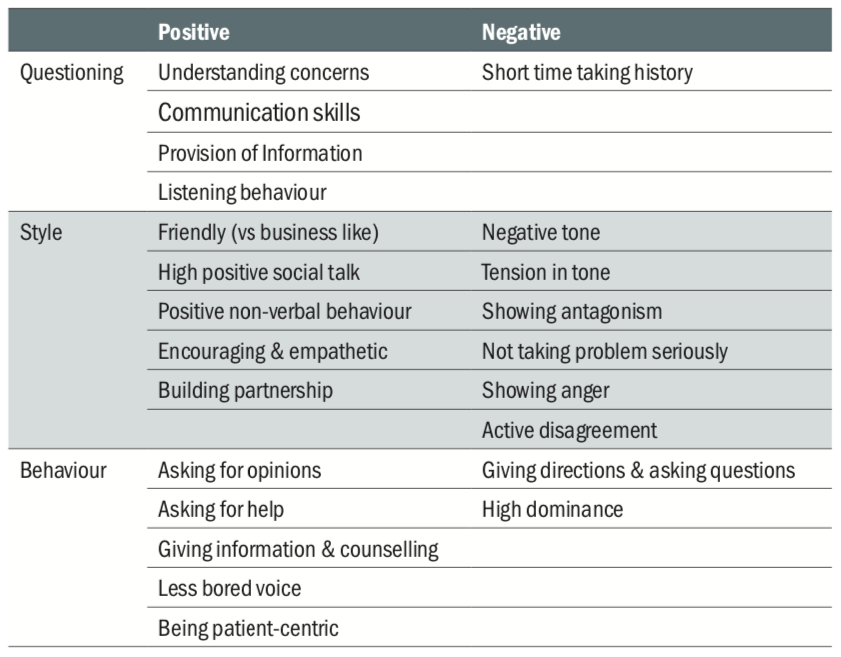

Good communication drives better patient satisfaction. A 1998 review of the literature4 looked at over 30 peer reviewed studies examining the relationship between doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction. The review explored the doctor’s communication in terms of the initial questioning, style and behaviour. Across all variables they found strong evidence to support the fact that communication has a significant impact upon patient satisfaction. Some of the drivers of positive and negative satisfaction are outlined in table 1.

Table 1: Communication drivers of positive and negative satisfaction

Within the sphere of optics, a 1990 study showed that the standard of care given by the optometrist was the overriding factor driving patient satisfaction.5 Breaking down the findings further, ‘empathy and support’ was the key factor in assessing the interpersonal skills of the practitioner followed by ‘information exchange’, ‘willingness to explain’ and ‘clarity of instructions’.

The impact of communication on patient satisfaction is well illustrated by the dentist Paddi Lund.6 Lund explains that fitting a crown is a technical procedure. The dentist may be the finest technician in the world, or just do an adequate job. As long as the patient has the appropriate pain relief, the result is the same to them. Their subsequent satisfaction, however, is most influenced by the relationship that they have with the practitioner ... and, indeed, all the practice staff.

Treatment conformance (compliance)

Health care professional communication is significantly positively correlated with patient adherence to the treatment. A meta-analysis of 106 peer reviewed studies showed that the patients of physicians assessed as having poor communication skills had a 19% higher risk of non-adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen.7 Non-adherence is more than 1.47 times greater among individuals whose physician is a poor communicator, and the odds of a patient adhering to instruction are 2.16 times better if his or her physician is a good communicator.

Treatment outcomes

While it is possibly somewhat intuitive that good communication skills be associated with better satisfaction and compliance, there is significant evidence that the benefits can be associated with better patient outcomes.8 Pain tolerance, speed of recovery, decreased tumour growth and better daily functioning have all been shown to be correlated with a sense of control coming from better doctor-patient interaction. While data on patient outcomes as a function of communication skills in eye care is not available, most practitioners are aware of colleagues who have a ‘chairside manner’ that leaves their patients rating their experience more highly than the objective signs of each interaction might have predicted.

Litigation

There is extensive data available on the impact of poor communication on legal cases against healthcare professionals. In one seminal study, the investigators looked at the communication skills of two matched groups of primary care physicians and surgeons.9 One group were free from ever having any malpractice claims made against them, while the other had at least two claims made against them during their career. The groups then had recordings made and analysed of their consultations. While no differences were found between the two groups of surgeons, a number of significant differences were found with the primary care physicians. Of the 29 different behaviours analysed, six could be shown as significant predictive factors in distinguishing between those doctors who had never had a malpractice claim against them and those who had. These factors were:

Physician facilitation; the use of statements to facilitate the consultation between patient and physician comments

Physician orientation; continual and appropriate orientation of the patient to the flow of the consultation

Patient gives information; sufficient allowance being made for the patient to provide information and have input to their therapy

Physician counsel; psychosocial and lifestyle factors being taken into consideration during the consultation

Physician laughs; appropriate use of humour during the consultation

Visit length; the group with no malpractice claims made against them undertook consultations which were, on aver- age, three minutes longer than the claims group

Within optometry in the UK, a poor history and symptoms is cited as one of the re-occurring themes in litigation cases,10 and it is rare that a fitness to practice hearing does not involve some element of miscommunication.

Communication audit

So, having established the importance of communication to both the professional and commercial aspects of optical practice management, the question of whether communication is important now becomes ‘how should the practice best manage their communication?’ Leaving it to chance would seem a risky strategy and a good starting point is to consider the communication touch points that a patient (or potential patient) engages with. Table 2 shows an example of what a means of recording communication activity in a practice might look like.

Table 2: Communication touch points; an example of a table for establishing communication flow in practice

Pulling together such a table is an excellent team-building exercise for the whole practice to engage in. Once completed, the next stage is for the practice manager/owner to consider who, within the staff is accountable for each element of the communication. The facilitator of such a discussion should avoid the ‘we all are’ response. While the whole practice team are responsible for the joined-up communication plan of the business, it is important that the accountability of making sure the activities are done correctly sits with a single person. This individual then will also become the point person for assessment and training of the element.The next stage in the process is for the practice team to try to self-assess how well each activity is carried out. Once again this is an excellent team-building exercise and need not be complicated. A simple four-point, colour coded scale can be used. The question ‘How good are we are at.....?’ can be answered by selection of one of the following:

- Better than average (green)

- Average (amber)

- Worse than average (red)

- We really don’t know (grey)

The value of this exercise is in the team thinking about how aware they are of the communication touch points within the practice. The facilitator of the meeting should aim for consensus, or at least a strong majority vote, but in many instances the most valuable follow-ups come from the realisation that staff often do not know how effective they are at communicating. Across this series of articles, we will be looking at how each of the core elements of communication can be assessed.

The final stage is to decide which are the most important touch points. Once again, the temptation to rank all as equally important should be avoided. This is also, to some extent, an exercise in relativity. The importance of one element may change with the realisation that others are particular weak points for the business. A good way of visualising this is by drawing up a simple grid, as shown in figure 1 and, using ‘post it’ notes to annotate each element of the communication framework on the grid depending on how well it is performed and its importance. This will help the practice understand where to prioritise its initial activity.

Figure 1: Communication framework audit grid

Communication and learning preferences

Having ascertained and evaluated the principle communication touch points of the practice, another very useful team-building exercise is to evaluate the practice team’s own communication styles and learning preferences. This helps in building trust and understanding between the team, as well as providing valuable information for the practice manager/owner for when they are carrying out future training. Having an understanding of the dif- ferent preferences that patients may have is also invaluable in being able to adapt one’s own style in order to get information across.

Learning

Everybody learns in different ways. In 1992, Fleming and Mills published the VARK model11 which describes four different principle learning styles, namely:

Visual; information depicted diagrammatically, for example as a chart, graph or spider diagram. The use of symbols, patterns and shapes to get information across. In interviews subsequent to this publication, Professor Fleming has reflected that ‘graphic’ may have been a better descriptor for this style of learning as it involves not just the use of pictures but other means of representation too.

Aural/auditory; learning through the spoken word, lectures, discussions and podcasts for example. Aural learners like to sort out their ideas by speaking, often repeating what has been said to the potential frustration of the teacher.

Read/write; learning through the written word, whether in books, articles or on PowerPoint slides. These learners seek out information on the internet and tend to be well read. They will typically access multiple sources of written information to seek the truth.

Kinaesthetic; at its simplest, this describes hands-on learning. People with this preference want to see and experience how something is done in order to internalise it. This may be through videos, demonstrations or simulations of an activity.

Since its launch, the VARK model has been refined and is available online along with supportive training material and further insights.12 An understanding of the potential different learning styles is useful for the practitioner when explaining a condition to the patient. Developing a variety of different means of describing conditions and treatments is time well spent for the practitioner.

Communication

‘Know thyself’ was inscribed upon pillars in the forecourt of the Temple of Apollo in Delphi and the idiom has been in use as a concept for philosophers and learners for nearly 3,000 years. Everybody’s communication style is a function of both their individual personality and their life experiences at any single point in their life. It therefore makes sense that, the better one understands one’s own personality and how this influences interaction with others, the better one is at communicating.

There are many personality tests available, ranging in scope from the four basic personality traits of Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument13 and DiSC profiles,14 to more detailed tools such as the Myers-Briggs indicator referenced earlier and also accessible online.15 These tests all provide a useful insight into how and why any individual perceives the world as they do and how they then are perceived by others with similar or different personalities. As an individual exercise, any one of these will help in developing a practitioner’s communications skills. When carried out at a practice team level, the greater depth of understanding achievable will contribute to the whole team’s efficiency in communicating among themselves. When undertaking personality assessment work, it is important to make sure that it is carried out by trained facilitators.

Summary

Communication skills are a requirement for GOC registration in the UK. Developing them not only improves patient satisfaction, but also compliance and treatment outcomes as well as reducing the risk of litigation. By carrying out a communication audit a practice can identify where its strong and week points are and understanding different learning and communication skills are a valuable tool in supporting the practitioner’s individual and team communication.

In the next article in this series, I will focus upon non-verbal communication.

Ian Davies is an optometrist now working as an independent motivational speaker, coach and business consultant.

References

General Optical Council CET competencies, downloadable from; www.optical.org/en/Education/CET/cet-requirements- for-registrants.cfm (accessed on 09/01/20)

Hardigan PC, Cohen SR (2003) A comparison of learning styles among seven health care professions: Implications for optometric education. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Science and Practice 1(1).

Steele CF, Rubin G, Fraser S (2006) Error classification in community optometric practice – a pilot project Ophthal. Physiol. Opt 26:106-110

Williams S, Weinmam J, Dale J (1998) Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Family Practice 15:480-492.

Thompson B, Collins M, Hearn G (1990) Clinician interper-

sonal communication skills and contact lens wearers’ motivation, satisfaction, and compliance. Optometry and Vision Science 67(9):673-678.Lund P (1994) Building the happiness-centred business. Solutions Press.

Haskard Zolnierek KB, DiMatteo MR (2009) Patient commu- nication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care 47(8):826-834.

Fong J, Longnecker N. (2010) Doctor-Patient communication: A review. The Ochsner Journal 10:38-43.

Levinson W, Roter D Mullooly JP et al (1997) Physician – patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physician and surgeons. JAMA 277(7):553-9

Hampson P 2019 Avoiding being sued. Optometry Today 1st April.

Neil D. Fleming ND, Mills C (1992) Not Another Inventory, Rather a Catalyst for Reflection. To Improve the Academy, Vol. 11, 1992, Page 137.

VARK – A guide to learning preferences (2019). Available at http://vark-learn.com

Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI). Available at http://herrmannsolutions

DiSC Personality types. Available at http://discprofiles.com 15 The Myers-Briggs Company. Available at http://eu.themyersbriggs.com/en