Pregnancy represents a physiological state associated with a large variety of maternal changes (including metabolic, hormonal, circulatory, immunologic, pulmonary and renal) that ultimately allow a normal gestation and the subsequent delivery of a healthy baby. In addition, pregnancy may change the course of pre-existing pathologies and also facilitate a large variety of gestation-related diseases. Moreover, treatments that are absolutely safe for non-pregnant individuals should be used with care during pregnancy as they could have a detrimental effect on the normal course of the gestation, on the foetus pre-term or on the baby after delivery.

This article provides a short overview of what is known about the use of various ophthalmic drugs during pregnancy.

General knowledge on ophthalmic drugs absorption

Ophthalmic drugs can be either hydrophilic or lipophilic. Lipophilic drugs penetrate through the cornea, conjunctiva and sclera, while hydrophilic drugs penetrate through the conjunctiva and sclera only. Once inside the eye, these drugs can be transported through either the vitreous and blood-retinal barrier or through the aqueous humour. In addition, up to 80% of an instilled drop can diffuse into the systemic circulation via the nasopharyngeal route.1

It is well known that the ocular bioavailability of the ocular drugs is only around 5 to 10%. This bioavailability depends on various factors, such as binding to proteins and enzymes in the lacrimal fluid, the thickness of the cornea and of the lacrimal film as well as on the presence of ocular pathologies, such as inflammation.1 In addition, it also depends on other medication that the patients are under, including systemic drugs that interact with the metabolism of the various ocular drugs. One such example is represented by the increase in the risk of cardiac events after the use of beta-blocker drops when the patients are also receiving oral treatments with drugs such as verapamil (an antihypertensive) or antidepressants such as paroxetine and fluoxetine.2

Ocular drugs in pregnancy

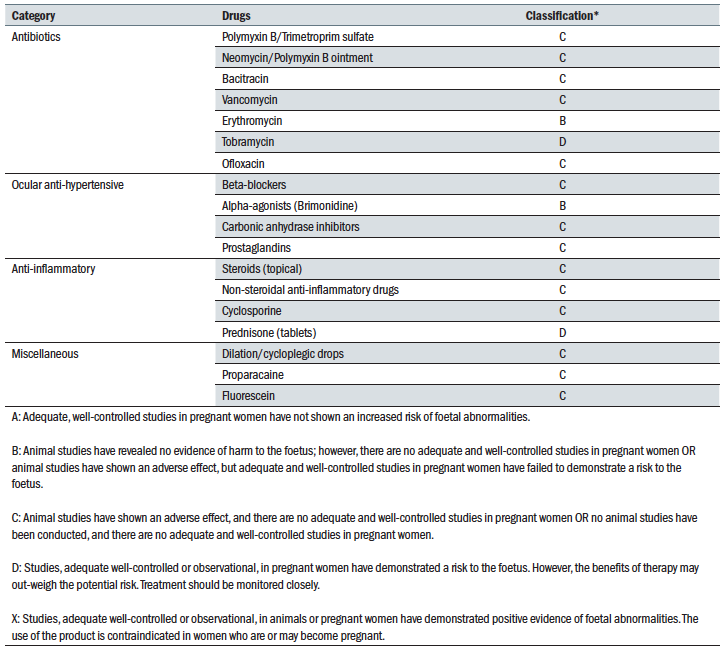

We might need to administer various drops to a pregnant woman either for diagnosis or treatment of various ocular conditions. Quite a few years back, in the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) produced a classification of various ocular treatments based on their safety according to various trials (table 1). Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that these data are limited as clinical trials that involve pregnant women are rare and are the subject of various ethical issues and legal constraints. To put it plainly, there is a huge need for more detailed information related to the safety and efficacy of medications in pregnancy and lactation, considering that, so far, many medications have been used safely and effectively in pregnancy with minimal risk to the foetus and mother. Indeed, the FDA also recognised this and, in 2014, they have published in 2014 a new rule entitled ‘Content and Format of Labelling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products: Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling’, which is also known simply as the ‘Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule’ (PLLR).3,4 They have also issued a draft document entitled Pregnancy, Lactation, and Reproductive Potential: Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products—Content and Format to serve as a guidance to industry in preparing PLLR compliant drug applications. Under the above rules, the categories listed in table 1 are being phased out. Nevertheless, these rules are currently criticised as being too complicated and lots of clinicians still refer to the old category designations.5

Table 1

Table 1

Antibiotics and antivirals

According to the UK Teratology Information Service (UKTIS), before prescribing a treatment with antibiotics in a pregnant woman we should consider several factors:

- The severity of the maternal infection

- The effects of not starting such therapy

- The potential toxic effect on the foetus

Some antibiotics used in ocular diseases are listed in table 1. However, one of the most commonly used drugs, topical chloramphenicol, is not listed. Chloramphenicol has a broad spectrum, is available over the counter and is not expensive. Although there are reports that the use of chloramphenicol can be associated with major side effects, such as aplastic anaemia and the ‘grey baby’ syndrome, it has been shown that the risk for such complications is very low if the recommended dose and the duration of the treatment is respected and if the treatment is stopped at the time of delivery.7 Nevertheless, the UKTIS recommends that treatment with chloramphenicol in pregnancy should be avoided if possible.

Other antibiotics that need to be avoided during pregnancy are:

- Neomycin

- Tetracycline

Safe antibiotics are:

- Erythromycin

- Ophthalmic tobramycin

- Ophthalmic gentamicin

- Polymyxin

- Quinolones

Antivirals should be used with caution. Acyclovir is generally well tolerated during pregnancy.

Another type of infection that can occur during pregnancy is toxoplasmosis, which is neither bacterial or viral. This disorder has the potential to cause severe ocular and mental disorders and even to result in stillbirth. Therefore, treatment is important. However, the drugs used to treat toxoplasmosis can also be toxic and, as such, the treatment and its effect should be monitored very carefully and done only under the supervision of an

obstetrician.

Ocular anti-hypertensives

Glaucoma during pregnancy is not a common occurrence. However, it can be possible that cases will present involving women with pre-existing juvenile or secondary glaucomas. In addition, as more and more women chose to have babies at later stages of their life, practitioners could also face the possibility of pregnant women over 40 years old that present with primary open-angle glaucoma. Despite the reality of facing such possibilities, the knowledge of managing such patients is somehow limited. Indeed, a survey performed among ophthalmologists in the UK in 2007 revealed that one-third of the responders were unsure how to initiate or adjust antiglaucoma medication in pregnant women.8

It has been recommended that glaucoma management plans for pregnant women should include the following points:9

- Assess plans for pregnancies in women suffering from glaucoma and inform them about the possibility of treatment change but also about other effects that pregnancy can have on the outcome of glaucoma. In addition, practitioners should also consider treating glaucoma before the pregnancy occurs using selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) or even surgery in those cases with high risk glaucomas.

- Consider the risk of various treatments. For some anti-glaucoma medication these are listed in table 1. Brimonidine is the safest drug to use in pregnancy; however, it is one of the most dangerous to use around delivery and after because it is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant in newborns.10 Beta-blockers and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) should be avoided in the first trimester but, after that, they are safe to use. Nevertheless, the use of beta-blockers should be stopped a few days before delivery because of the risk of causing bradycardia and respiratory problems in newborns. Prostaglandins can increase uterine contractions and, as such, should be avoided throughout pregnancy as they can cause miscarriage and premature labour.11

- There is no data on using the newest classes of anti-glaucoma medications, such as rho kinase inhibitors, in pregnancy.

- Reassess treatment closer to delivery. As stated above, brimonidine and beta-blockers should be stopped before delivery. Also assess the risk that the effort occurring during delivery can have on the optic nerve health, due to the possibility of a huge IOP increase. Nevertheless, there is no data about the levels of IOP during delivery in pregnant women with glaucoma.

- Assess the risk of glaucoma medication passing through breast milk. This can happen and, after delivery, prostaglandins may be the safest alternative. CAI are also indicated during this time.

- Avoid glaucoma surgery during pregnancy. This is due to the fact that the general anaesthetics and antimetabolites used during such procedures can have harmful effects on the foetus. If the procedures cannot be avoided, all measures should be put in place to delay it past the first trimester and performed only using local anaesthetics. Post-surgery, care should also be paid to the use of antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs (as discussed elsewhere in this article).

In addition to the above point, always consult with the obstetrician and neonatologist in order to ensure that both mum and baby are safe at all times.12

Anti-inflammatory and anti-allergy drugs

Although animal studies have indicated that topical steroids can potentially have a teratogenic effect, human studies have not confirmed this. Nevertheless, due to lack of studies in pregnant women, the use of topical steroids in pregnancy should only be reserved to extreme cases.

NSAIDs are thought to be safe if administered in the first 30 weeks of gestation but after this period they are associated with various complications such as premature closure of ductus arteriosus (a blood vessel connecting the trunk of the pulmonary artery to the proximal descending aorta of the foetus) and oligohydramniosis (deficiency of amniotic fluid).13

Similar to steroids, there is limited data regarding the use of anti-histamines in pregnant women. Despite the lack of data, the UKTIS states that sodium cromoglicate, a mast cell stabiliser used for the treatment of allergic conjunctivitis may be used in pregnancy if clinically indicated.

Diagnostic drugs

Mydriatics and cycloplegics

There are no reports indicating adverse effects on mother or foetus after the use of atropine, phenylephrine, homatropine, cyclopentolate or tropicamide. Despite this, phenylephrine is generally avoided in pregnancy because it can induce vasoconstriction with possible detrimental effects on the circulatory system.

It is not known if mydriatics or cycloplegics are excreted in the breast milk.

Anaesthetics

There are also no reports on adverse effects after the use of lidocaine, oxybuprocaine, proxymetacaine or tetracaine in pregnancy.

Other diagnostic drugs

The occasional use of fluorescein for the diagnosis of ocular

surface abnormalities is of no consequence for the baby. Nevertheless, fluorescein given topically has been detected in the breast milk and, as such, it is recommended that mothers do not nurse for eight to 12 hours after fluorescein instillation (American Academy of Ophthalmology).14

It has also been shown that even if fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographies can be safely performed in pregnant women, most ophthalmologists avoid the use of such techniques especially in the first trimester of gestation.

Conclusion

We still lack evidence for the risk of giving any drops to pregnant women. As a general rule and if at all possible, avoid any drugs in the first trimester when the foetus’ organs develop. Nevertheless, when absolutely necessary and using all known precautions for safe administration, ocular drugs can be prescribed, especially when the benefit is far greater than the possible risks. In addition, appropriate measures should be applied whenever applying eyedrops in order to avoid their systemic absorption in large quantities, especially in pregnant patients with associated morbidities or under other treatments. In addition, practitioners should be aware of any systemic medications that the patients receive, as well as of their potential interactions with the prescribed ocular medication.

Dr Doina Gherghel is an academic ophthalmologist with special interest in inter-professional learning for optometrists.

References

- Farkouh A, Frigo P, Czeika M. Systemic side effects of eye drops: A pharmacokinetic perspective. Clin Ophthalmol 2016; 10: 2433-2441

- Macnpaa J, Pelkonen O. Cardiac safety of ophthalmic timolol. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2016; 15:1549-1561

- Food and Drug Administration. Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products: requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Fed Regist 2014;79(233): 72064–72103. Available at: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-12- 04/pdf/2014-28241.pdf

- Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential: labeling for human prescription drug and biological products — content and format: guidance for industry. December 2014. Available at: www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/ GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ UCM425398.pdf

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5083079/pdf/ptj4111713.pdf

- https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/229-drugs-in-pregnancy.htm

- Chung CY, Kwok AKH, Chung KL. Use of ophthalmic medication during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J 2004; 10: 191-195

- Vaideanu D Fraser S. Glaucoma management in pregnancy: a questionnaire survey. Eye (Lond) 2007; 21: 341-343

- Camejo L. Five pointers on glaucoma in pregnancy. Glaucoma Today, 2019, July/August

- Fudemberg Sj, Baptiste C, Kats LJ. Efficacy, safety and current applications of brimonidine. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2008; 7: 795-799

- De Santis M, Lucchese A, Carducci B et al. Latanoprost exposure in pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 138: 305-306

- Strelow B, Fleischman D. Glaucoma in pregnancy: an update. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2020; 31:000-000

- Torloni MR, Cordioli E, Zamith MM et al. Reversible constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus after maternal use of topical diclofenac and methyl salicylate. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2006; 27: 227-229

- www.aao.org/focalpointssnippetdetail.aspx?id=9c240b2e-6134-4926-a91d-6c69b1ee4a3d (accessed 09/02/20)