Within the first seven seconds of meeting someone a person is able to make up to 11 opinions about the individual. One of the opinions is based on what is said, four on how it is said and the remaining six on body language. Given that the opinion that patients have on the clinician and practice staff has a profound impact on the outcome of their visit, the importance of understanding body language cannot be underestimated. This article will review the key aspects of non-verbal communication as they pertain to optical practice.

First impressions count

Everyone only gets one chance to make a first impression and, as we have said already, we have less than 10 seconds to make it. Given its importance it should not be left to chance and covered at regular staff training sessions. Within a practice there may be up to four opportunities to make a first impression (figure 1). Each should be considered in turn:

Figure 1: Practice first impressions

Figure 1: Practice first impressions

Front desk staff

It is easy to make the case that this is the most important interaction that a patient, particularly one who is new to the practice, has. Front desk staff set the tone for the culture within the practice. They are also, in many cases, first in line to deal with patient complaints. Front desk staff also have the most challenges put upon them that are out of their control. Phones ring, more than one patient may come in at the same time, another member of staff may be waiting to book an appointment and, while all this is going on, they have to maintain the calm, professional, front facing face of the business.

It almost goes without saying that front office staff must like dealing with people and have an aptitude towards multi-tasking. They should also:

- Smile

The single most affirming signal that one human being can give another is a smile. A smile indicates an acceptance of the person being smiled at. Smiling is also good for the individual with studies showing that the act of smiling releases neuropeptides that fight stress, reducing heart rate and blood pressure. A smile need not (in fact should not) be a big cheesy grin, but simply upturning the corners of the mouth and consciously thinking about ‘lifting’ the muscles of the face. - Make eye contact

Making eye contact with someone is a clear indication that you have seen them and are aware of their presence. This is especially important if there are multiple patients vying for attention at the same time, or if the staff member is on the phone. The eye contact should be brief enough to make sure that the recipient knows that they have been acknowledged, but not too long to make the patient feel uncomfortable or to indicate that a response is expected from them. Staff should also be careful not to roll their eyes in exasperation in dealing with one patient, either in reception or on the phone towards another. While it might seem amusing, it passes on the clear message that not all patients are treated with the same respect. - Open armed gestures

This will be covered later in the article and is important for front office staff. They should avoid pointing, especially with a pen in hand. If they need to gesticulate to a patient to take a seat this should be done with an open palm which indicates an invitation rather than an instruction.

Optical assistants

The role of the optical assistant in pre-screening is becoming increasingly important in conducting an efficient and effective comprehensive eye examination. For many patients though, the assessments being carried out are new and unfamiliar and it is important that they be put at ease. Best practice should always be that the optical assistant, or technician carrying out the assessment goes to meet the patient in the reception area. The same points that apply to front office staff – smiling, making eye contact and open armed gestures – are equally important to the first impression of the optical assistant. While not being an element of non-verbal communication, it is also important from this stage of the patient journey onwards that each individual introduces themselves and use the patient’s name. Having the front office staff make a note of any phonetic pronunciation and how they would prefer to be referred to is also useful.

Once in a position to carry out the pre-screening, the optical assistant should make sure that the patient understands what the procedures are, how they will be carried out, and how the results will be communicated back. With each piece of equipment, the conversation should happen, as far as possible at the ‘patient side’ with the operator either sitting or being at the same eye level. Demonstrating the puff of air from a non-contact tonometer is well established, consideration should be made to demonstrating other functionality of the equipment, for example flashes of light or noises. The more relaxed and informed the patient is, then the more effective and efficient the assessment will be.

Finally, and this applies to the eye exam as well, sharp intakes of breath are to be avoided at all costs.

Optometrists

By the time the optometrist gets to make a first impression, the patient will already have formed a pretty clear opinion of the practice. They may have already met, or had an interaction, with two or three other staff members who, while being important parts of the patient journey, were not who the patient came to see. The basics of the introduction for the optometrist are the same as for other staff members. Ideally the optometrist will come out of their consulting room to meet the patient, if not then they should not only be ready, but appear to be ready for the patient coming in. If the practitioner is running late, or has been having a particularly challenging day, it is especially important that the first impression is positive, and the patient made to feel welcome. Standing up, using the patients name and openly gesturing towards the consulting room chair can all contribute to this.

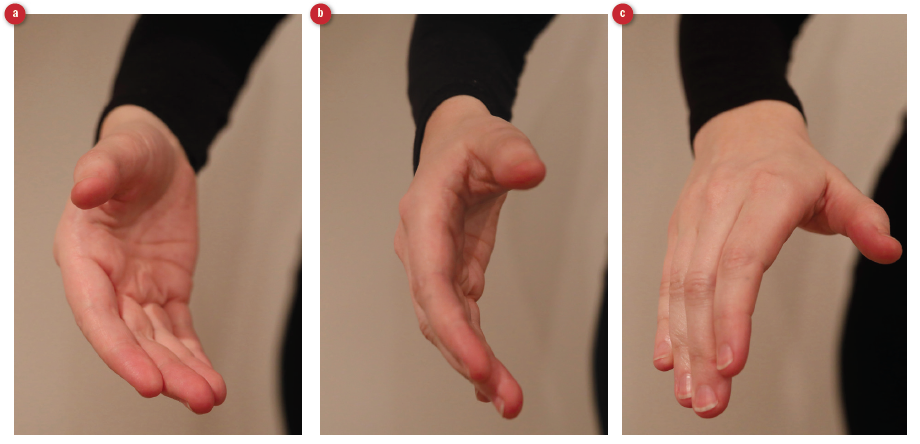

The use of a handshake, in the absence of specific cultural norms that will be touched on later, is largely a personal decision. In the case that a handshake is offered by the patient, it should be reciprocated. The art of a good handshake is to match the grip of the person who offers it and sense the time to release the grip based on that of the other person. If a decision to shake patients’ hands routinely is made, then the offer of the handshake should be neutral to open (figure 2) and the strength of the grip matched. Post-handshake and prior to any physical contact with the patient the practitioner should wash their hands to both avoid, and demonstrate the importance of, hand hygiene. At the time of going to press, all practice staff should be advised to keep up to date with guidelines about the risk of direct contact and the requirement to minimise the risk of the spread of the coronavirus.

Figure 2: a) Open, b) neutral and c) dominant handshake styles

Dispensing handover

Very often the ‘last’ first impression to be made is from the optometrist to the dispensing optician, who, like others before in the journey, should be prepared, interested and attentive to the patient. The most obvious non-verbal communication is going to come from any frames and lenses that the dispensing team are wearing. These should reflect the latest frames that are available and provide immediate visual clues to the patient. In a similar vein, but outside the scope of this article, there is great merit in whoever in the practice team teaches contact lens application and removal wearing contact lenses, so that they are able to demonstrate on themselves.

Posture and Children

Any practice that sees a significant number of children needs to make the environment child friendly. It is also important to consider how all staff members body language and posture can impact on the way they are seen by a child. The average height of a woman in the UK is around 5ft 5in and a man 5ft 10in. The

average height of a child going for their pre-school eye exam is around 3ft 4in, so this means that they will be looking up to the practitioner at an angle of around 30 degrees, and the consulting room will look very different from that which is seen by an adult (figure 3). Adults tend to look aloof from a lower angle and this is one occasion when the practitioner may be wise to be sitting down when the patient comes into the room, or, slowly getting down to the child’s height.

Figure 3: Perceptions of a practitioner from (a) a child’s viewpoint and (b) and adult’s viewpoint

Hand and arm movements

Being aware of the impact of hand and arm position and movements are important in both assisting communication and reading signals from the patient.

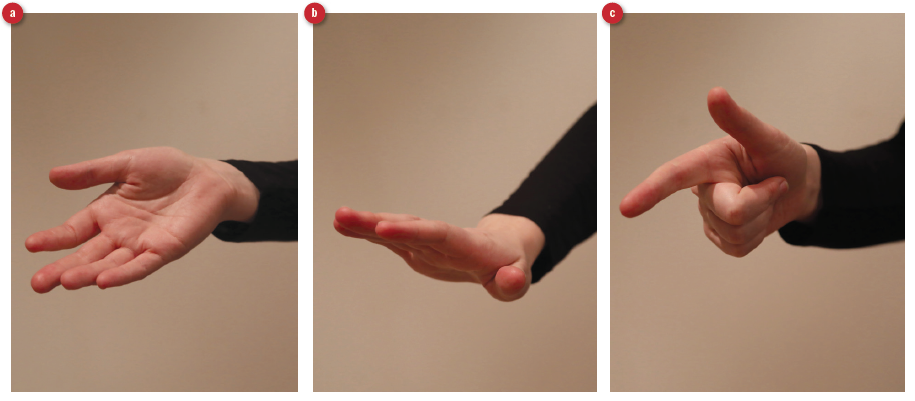

Transmitting information

Hand positions (figure 4) can play an important part in aiding the transmission of information to the patient (or practice staff). Having the palms visible is a non-threatening, open gesture that invites trust. It is also an intermediate step to a handshake should the patient be looking for one. Having the palm down transmits a very different message. It signals a more assertive, authoritarian and dominant position. It is a powerful, non-verbal signal to someone to stop talking, and as such should be used cautiously with an appropriate verbal explanation, for example ‘let me just stop you for a minute while I take a note.’ While our mothers may have told us that it is rude to point, pointing a finger at someone is the most commanding hand signal an individual can give. It should only be used when it is critical that a point needs to be understood and never to someone from Malaysia or the Philippines where it is insulting.

Figure 4: Interpretation of hand gesture; (a) open; (b) assertive; (c) commanding

Receiving information

Learning to read a patient’s body language provides many clues as to the extent that information is being taken in and the validity of information that is being expressed. While those who sit with arms crossed claim to do so for reasons of comfort, it generally indicates a negative, defensive or nervous attitude. Research has shown that students who sit with crossed arms take in 38% less information than those who sit with open arms.1 Asking a patient to hold a document while explaining what you want them to do is a very fast and effective way of getting them to uncross their arms. When an infant tells an untruth, they tend to put their hands to their mouth. This behaviour translates to adulthood and any statement being told while the patient moves their hand to any part of the face should be taken with some level of scepticism. Untruths are also rarely told while maintaining direct eye contact. A patient listening with a closed hand on the chin and the index finger pointing upwards (figure 5) is indicating not only a lack of interest, but also a challenge about what is being said.

Figure 5: A gesture easily misinterpreted as sceptical or disinterested

Figure 5: A gesture easily misinterpreted as sceptical or disinterested

Cultural Awareness

An eye examination and dispensing of any type require close proximity of the practitioner to the patient. Touching a person’s face is one of the most intimate acts that a person can do to another. There are very few instances in someone’s life when they allow a stranger to get to within 1cm of their face, as an optometrist needs to do when carrying out ophthalmoscopy. The practitioner needs to be aware of social and cultural norms in managing their patients.

All patients have the right to have a chaperone present during an eye examination, and, equally the practitioner should have no hesitation in having a chaperone present if they feel uncomfortable with any particular patient. Guidelines are provided by all professional bodies and good practice is to have a chaperone statement available for all patients.2 In all patient interactions the key is to avoid sudden body or hand movements and explain what is about to happen before moving closer to the patient and why it is important. Beyond an initial handshake, where appropriate, there should be no reason for the practitioner to touch the patient for any non-clinical reason.

There are additional specific cultural sensitivities that the practitioner should be aware of, which go beyond the scope of this article. A practitioner working within a multi-cultural environment should be aware of the cultural norms for each of the groups that they are likely to see.3 A good rule of thumb is: if in doubt ask, and always explain what you are about to do and why you need to do it.

Summary

Non-verbal signals are powerful determinants in effective communication. Understanding the importance of the first impression is critical to all staff within a practice environment. The eye examination places a patient in an unfamiliar and stressful environment, and the effective use of positive body language will help in reassuring a patient and, in so doing, make the exam more efficient and effective.

Ian Davies is an optometrist now working as an independent motivational speaker, coach and business consultant.

References

- Pease A, Pease B (2004) The Definitive Book of Body Language. Orion.

- Model Chaperone Framework for Optometry and Opticians (2005) at https://www.loc-net.org.uk/media/1751/joint_advice_on_chaperoning_policy.pdf

- Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust. Respecting the Religious and Cultural needs of patients. At www.gmmh.nhs.uk/download.cfm?doc=docm93jijm4n901