A novel coronavirus (CoV), the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), results in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the rapid spread of cases of COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The global response to COVID-19 has resulted in substantial changes to business and social practices around the world. With concerns existing around the pandemic, many reports relating to how best limit the chance of infection have been shared via various news outlets and on social media, with significant amounts of misinformation and speculation being reported. Among these, recent rumours have circulated stating that contact lens wear is unsafe, that wearers of contact lenses are more at risk of developing COVID-19, that certain contact lens materials are ‘riskier’ than others and that contact lens wearers should immediately revert to spectacle wear to protect themselves. How true are these statements, and are they supported by evidence? Importantly, are contact lens wearers increasing their risk of contracting COVID-19 by wearing contact lenses? Furthermore, what are the ramifications of a potential reduction in the availability of local ophthalmic care for contact lens wearers during this pandemic?

Coronavirus

Before answering these questions, it is first important to review the known structural biology and pathophysiological mechanism of an infection caused by SARS-CoV-2. All CoVs contain ribonucleic acid (RNA) as their genetic material, which is surrounded by a protein shell called a nucleocapsid. Like other CoVs, SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped virus, meaning its nucleocapsid is surrounded by a lipid bilayer. SARS-CoV-2 has three proteins which are anchored into and protrude from the envelope, including spike proteins.2 These proteins form the corona that can be seen by electron microscopy and gives the name to the CoVs (figure 1). The spike proteins are glycoproteins that have high affinities for angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), a component of the renin-angiotensin system found in many human tissues.3 This affinity is believed to allow entry of the virus into host cells, where the virus releases its RNA into the host cell, leading to viral replication and further infection.

Figure 1: The SARS-CoV-2 virus

Figure 1: The SARS-CoV-2 virus

Coronavirus and contact lens wear

Coronaviruses are capable of producing a wide spectrum of ocular disease, including anterior segment diseases such as conjunctivitis and anterior uveitis, and posterior segment conditions like retinitis and optic neuritis.4 While these ocular manifestations are possible for someone who has been infected with the virus, what is known about the potential for transmission of the virus via the eyes, or indeed if contact lens wear increases risk?

A PubMed search on April 5, 2020 found no evidence that contact lens wearers are more likely to contract COVID-19 than spectacle wearers. The likely belief for this concern relates to the fact that SARS-CoV-2 has been isolated in tears, albeit infrequently,5 and also that the virus is known to be transferred by hand contact, and thus could be transferred to contact lenses during their application and removal. In one report, positive tear and conjunctival secretions occurred in a single patient who developed conjunctivitis from a cohort of 30 patients with novel CoV pneumonia.5 In another report,6 64 samples of the tear film from 17 patients with COVID-19 showed no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 by viral culture or reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Further, the frequency of conjunctivitis in patients with COVID-19 reported to date is low, at <3%,5,7 although it has been suggested that CoVs could possibly be transmitted by aerosol contact with the conjunctiva in patients with active disease.5,7-11 However, the question of whether COVID-19 can occur through conjunctival exposure remains unknown.12 Recent papers concluded that ‘The eye is rarely involved by human CoV infection, nor is it a preferred gateway of entry for human CoVs to infect the respiratory tract’13 and that ‘The results from this study suggests that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission through tears is low’.6 Thus, to date, there are no findings that support concerns that healthy patients are more at risk of contracting COVID-19 if they are contact lens wearers.

It could be argued that COVID-19 is so new that such data would not yet exist. However, the lack of evidence from previous outbreaks of coronavirus disease, including SARS in 2002-2003, suggests that the risk of developing COVID-19 from contact lens wear is low. It is informative to consider viral diseases that are transmitted by direct contact and which could be used as a surrogate for evaluating the risks of COVID-19 in contact lens wearers. One such example is epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC), caused by the non-enveloped DNA virus adenovirus. This disease is highly contagious, spreads rapidly through direct contact, accounts for 65-90% of viral conjunctivitis cases14 and has been implicated in actively transmitted disease in eye care clinics and other common healthcare settings where there is close contact between healthcare providers and patients.15-19 However, a review of the literature appears to show no increased risk for EKC in those wearing contact lenses versus non-lens wearers, with a reported frequency of 3-15% in contact lens wearers.18,20

SARS-CoV-2 spreads primarily via person-to-person contact through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.21,22 However, it also could be spread if people touch an object or surface with virus present from an infected person, and then touch mucosal surfaces such as their mouth, nose or eyes.22-24 Given that contact lens wearers must touch their eyes when applying and removing their contact lenses, it is understandable this has been raised as a potential concern for increasing their risk of exposure to the virus. The consistent, unambiguous advice to protect individuals from the virus is to employ frequent handwashing with soap and water. The lipid envelope of the virus can be emulsified by surfactants such as those found in simple soap, which kills the virus.22,25 Best practice advice for contact lens wearers includes the same instructions that should be imparted under all situations, regardless of the COVID-19 pandemic. When using contact lenses, careful and thorough hand washing with soap and water followed by hand drying with unused paper towels (termed ‘kitchen roll’ in the United Kingdom) is paramount. For contact lens wearers, this should occur before every contact lens application and removal, and this process reduces the risks of infection and inflammatory responses and is highly effective.26 It follows that as long as contact lens wearers are using correct hand hygiene techniques, they should be limiting any virus transmission to their ocular surface, and indeed, as already stated, there is currently no evidence that they are at any higher risk of developing COVID-19 infection than non-wearers.

A further consideration is the length of time the virus is viable on different surfaces, and in turn, the potential for it to bind to contact lens materials. Addressing the former, a recent study showed that the aerosol and surface stability of both SARS-Cov-2 and its predecessor, SARS-CoV-1 (the viral strain associated with the prior SARS epidemic) was similar.27 Specifically, both viruses could be detected in aerosols for up to three hours, on cardboard for 24 hours, and on plastic and stainless steel for two to three days. The persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces such as plastic and silicone rubber surfaces has recently been published as a review, although the studies did not include SARS-CoV-2.28 To date, no studies have addressed whether SARS-CoV-2 binds to contact lens materials of any type and thus no knowledge exists of whether there are differences between contemporary materials (such as hydrogel and silicone hydrogel) or whether different periods of replacement have any impact.

A final consideration is that of contact lens disinfection. To date, no evidence exists of the ability of currently marketed contact lens solutions to disinfect SARS-CoV-2, and evidence concerning the ability of contemporary care solutions to disinfect viruses remains equivocal.29,30 Stretching back more than 30 years, contact lens care systems have been shown to be effective at inactivating both Herpes simplex and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),31,32 particularly when a rub step was included,33 and a rub and rinse step has been found to more effectively remove virus from contact lenses compared to when no rubbing occurred.30 A recent paper showed that benzalkonium chloride could slow or halt adenovirus.34 Most modern lens care systems include a surfactant,35 and given that SARS-CoV-2 has a lipid envelope, it is plausible that a rub-and-rinse of the lens with such a care system may well be effective at killing the virus, but further work in this area is required to confirm this. Inactivation of coronaviruses by various biocidal agents, including some found in lens disinfecting solutions has been investigated. Significant reductions (>4log10) in human coronavirus were seen in 60 seconds or less for both 0.5% hydrogen peroxide and 0.23% povidone iodine, both being used at notably lower concentrations than that found in modern contact lens disinfection systems.28

Coronavirus and spectacle lens wear

Recent news reports have made a number of suggestions about spectacles, including that they can provide some protection against the virus, and that they reduce the number of times people touch their face compared to contact lenses. What does the published evidence to date tell us about this issue?

A systematic review of the literature shows there is no scientific evidence that wearing spectacles provides protection against SARS-CoV-2 or other viral transmissions, although this concept has been recently proposed in the media.36-38 This belief around the safety of spectacles likely exists because of the guidance to use approved personal protective eyewear (medical masks, goggles or face shields) in certain settings involved in the care of infected patients.39 However, these goggles and shields provide very different protection to that afforded by standard spectacles, a difference recognised by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), who state that ‘personal eyeglasses and contact lenses are not considered adequate eye protection.’40

Despite the CDC’s clear delineation between standard spectacles and approved personal protective eyewear, it is understandable that a misplaced belief still exists for spectacles being preferable to contact lenses. There are a number of confounding factors, however, which do not support this theory. Consider firstly, part-time wearers of spectacles who only use their spectacles for occasional distance use or for reading. Their assumed ‘protection’ is intermittent, and additionally their increased frequency of putting on and removing their spectacles adds to the potential of touching their face each time, possibly in the absence of hand washing. Another point to consider is that some viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 can remain on hard plastic surfaces (similar to those found in spectacle frames and lenses) for hours to days.28,41-43 Upon touching their spectacles, any virus particles could be transferred to the wearers’ fingers and face and thus adequate hand hygiene practices should also extend to the regular handling of spectacle and sunglass frames to prevent transmission of viral particles to the fingers and subsequently to the face. Spectacles should be regularly cleaned with soap and water and dried with a paper towel to remove any adhered viral particles. However, given this is relatively new advice, without education, it is currently unlikely that spectacle wearers would adhere to such a process.

The importance of hand hygiene

Outside of contact lens and spectacle wear, how often do people touch their face in general, and what is the best advice to give them?

Hands are a common vector for the transmission of respiratory infections.44 An observational study of medical students examined the frequency with which they touched their face.45 On average, each of the students touched their face 23 times per hour. Of all face touches, 44% involved contact with a mucous membrane (eyes, nose or mouth) versus 56% that involved contact with non-mucosal areas (ears, cheeks, chin, forehead or ear). Of the mucous membrane touches, 36% involved the mouth, 31% the nose, 27% the eyes, and 6% were a combination of these regions. Given this very high number of face touches, hand washing becomes extremely important as a method to prevent transmission of any pathogenic organism from the fingers to the mucous membranes of the face. In relation to COVID-19, this advice, as recommended by the WHO and CDC, applies to everyone whether they use contact lenses, spectacles or no vision correction at all.

In addition to common soaps used in hand washing, the SARS-CoV-2 virus is very likely susceptible to the same alcohol and bleach-based disinfectants that eye care practitioners commonly use to disinfect ophthalmic instruments and office furniture.28 To prevent SARS-CoV-2 transmission, the same disinfection practices already used to prevent office-based spread of other viral pathogens are recommended before and after every patient encounter. Many of these steps have been summarised in a recent editorial,46 which covers a number of important considerations for conducting safe clinical practice during the pandemic.

The CDC and WHO recommend that people clean their hands often to reduce their risk of contracting the virus. Specifically, they advise all people to:

- Wash their hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds especially after they have been in a public place, or after blowing their nose, coughing, or sneezing.

- If soap and water are not readily available, they should use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. They should cover all surfaces of their hands and rub them together until they feel dry.

- They should avoid touching their eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

Access to clinical care and considerations for contact lens wear during the pandemic

Evidence suggests the safety of contact lens wear has not altered due to the pandemic and that appropriate hygiene considerations for contact lens wear and care should be the same as those always recommended. However, given access to routine and emergency eye care may be substantially different during the pandemic, what should eye care professionals bear in mind when discussing contact lens wear with their patients?

A key consideration is for practitioners to be cognizant of local clinical care facilities during the course of the pandemic and to act to minimise the impact of contact lens-related adverse events on the wider healthcare system, which may be stretched as staff are moved from providing ophthalmic care to other areas more directly related to COVID-19 patients. The implications here will necessarily vary according to local and regional considerations. Routine eye care has been suspended in many countries, with optometric practices moving to provide emergency services only.

In the United Kingdom, practitioners should work to manage cases within an optometric framework rather than refer into the National Health Service where possible. This could include telephone contact with patients reporting contact lens problems and/or a video consultation to enable rapid triage and management, reducing the need for burdening other clinical colleagues in general practice or hospital settings. Some cases may be best managed by referral to optometric colleagues licensed to practice as independent prescribers (therapeutically qualified optometrists). In other cases, local minor eye conditions services (MECS) may be an alterative care pathway. Under this service patients are sent to local optometrists who have undergone accredited training in advanced optometric care, or suitably accredited contact lens opticians, that can triage whether referral to ophthalmology is required and, where possible and within their scope of practice, treat minor eye conditions. It is imperative that eye care professionals avail themselves of the relevant options as early as possible in order to act quickly in the interests of both their patients and the wider healthcare system, and not begin to investigate the possibilities only after a contact lens wearer reports having some form of adverse event.

In North America and several other countries, therapeutically-trained optometrists are more likely to be the first port of call for contact lens patients with clinical adverse events, although again, most authorities have required deferral of non-emergent, routine care. Here also, appropriate pathways need to be considered and enacted where a reduced level of routine eye care is available. In countries where contact lens fitters and practitioners are less likely to offer clinical care to patients with clinically significant adverse events, management pathways and advice should again be considered to minimise the impact on the wider healthcare system.

It is particularly imperative during the ongoing pandemic that practitioners redouble their efforts to provide clinical advice to their patients to minimise contact lens complications, not least because many parts of the world are in forms of ‘lockdown’ and even leaving home to seek attention may not be straightforward. The simplest approach, as recommended by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, would be to cease contact lens wear and return to spectacles during this time.47 However, given the personal motivation individuals may have for wearing contact lenses, or indeed those wearing lenses for a clinical reason (keratoconus for example), this suggestion is likely not practical for many contact lens wearers. In the UK, the General Optical Council has taken a pragmatic approach to contact lens wear and supply during the pandemic. Recognising the highly challenging circumstances and the need to depart from established procedures,48 it has offered guidance enabling practitioners to exercise professional judgement on continuing supplies of contact lenses, following remote consultation, even in the case of an expired specification.48 This action should significantly reduce any temptation from patients to use lenses beyond the recommended replacement interval. Practitioners should also act to ensure patients receive a supply of their prescribed lens type and communicate this appropriately, to dissuade patients from sourcing alternative (non-prescribed) lens brands via online lens retailers. In the US, the American Optometric Association notes that patients should contact their Optometrist if their contact lens prescription is nearing expiration, but goes on to mention that no federal rules relating to the Contact Lens Rule prescription verification process have been suspended or waived.49

It is important to remember that by any absolute measure, contact lens wear is a safe form of vision correction for millions of people around the world. A review of 1,276 soft contact lens wearers records, across 4,120 visits, found 82% did not present with any complications during the observation period of more than two years.50 The frequency of more significant complications such as corneal infiltrative events (CIEs) and microbial keratitis are well understood. The annual incidence of symptomatic CIEs in daily reusable soft lens wear is around 3%, and nearly zero in daily disposable wear.51 The incidence of symptomatic CIEs in extended wear is higher, with a two to seven times increased risk compared to daily wear.52-54 Annual incidence of microbial keratitis (MK) varies by modality, and is around two per 10,000 wearers with daily wear of soft lenses,55,56 increasing to around 20 per 10,000 wearers in extended soft lens wear, irrespective of material type.55,57-59

Considerations for advising contact lens wearers

What steps can eye care professionals take to further support their contact lens wearers during the pandemic?

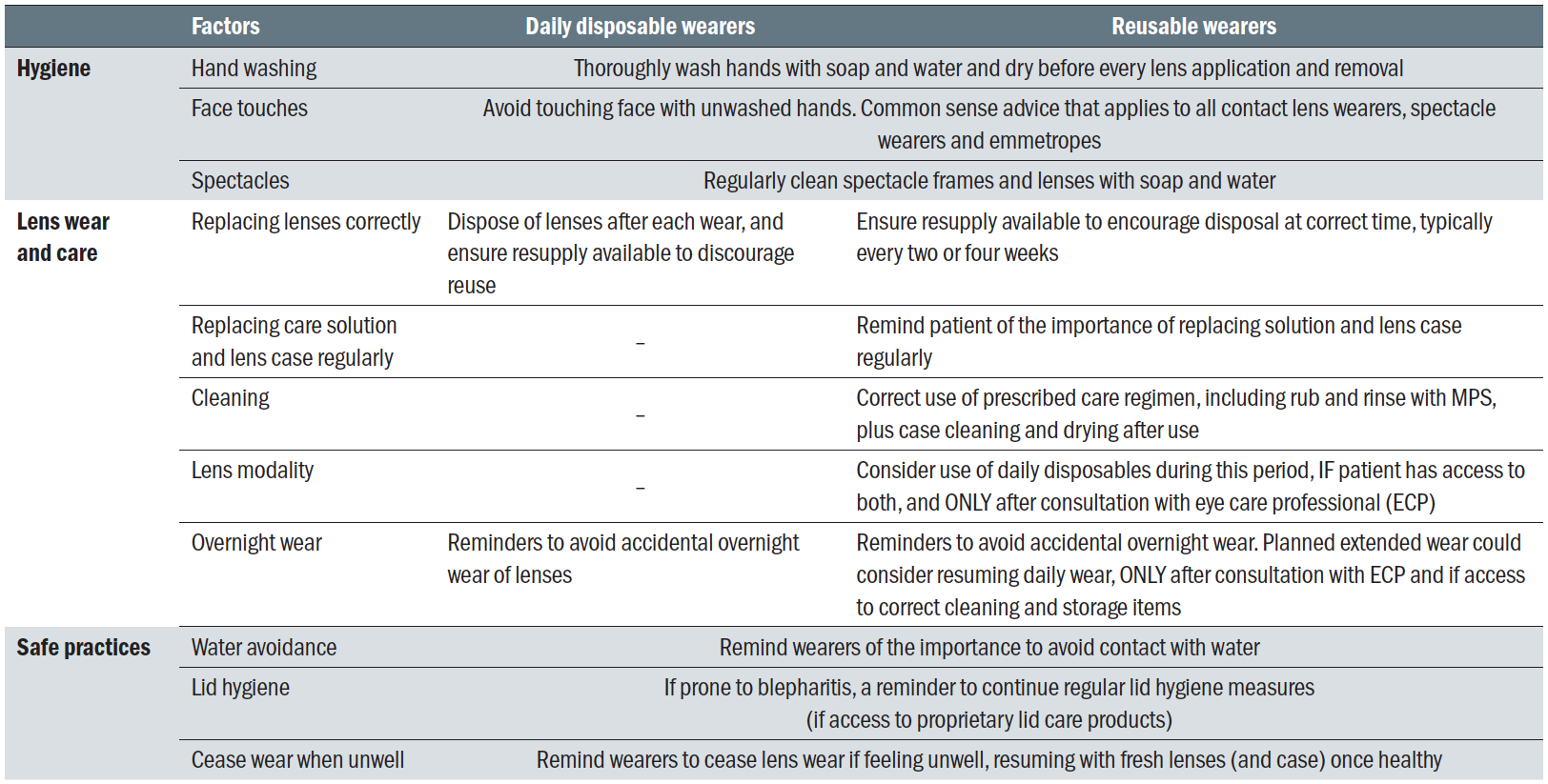

The risk factors that result in CIEs and MK are well understood. The relative risks of developing CIEs are summarised in the comprehensive review by Steele and Szczotka-Flynn,60 and include non-modifiable factors such as younger age (1.75-2.61x), higher prescription of 5 dioptres or more (1.21-1.6x) and history of a previous event (2.5-6.1x), along with modifiable risks such as overnight wear (2.5-7x), bacterial bioburden on the lens and lid margins (5-8x), and lens replacement schedule – reusable compared to daily disposable (12.5x). MK is associated with many similar factors, including overnight wear,55,58,59 and for daily wear, poor lens and storage case hygiene, infrequent lens case replacement, exposure to water and smoking.61,62 Risk factors for MK in daily disposable wearers are more frequent use, any overnight wear, less frequent handwashing, and smoking.63 While it is not possible to change a non-modifiable risk factor such as the age of a patient, there are significant opportunities to address modifiable behaviours (table 1). Given the reduced incidence of CIEs in wearers of daily disposable lenses,50,51 this form of lens wear seems ideal in a time of reduced clinical provision. Some patients hold supplies of both reusable and daily disposable contact lenses, with the latter normally used for sports or holidays. With appropriate practitioner discussion, a move to using daily disposable lenses could be considered at the current time.

Table 1: Modifiable risk factors to consider for patients to help them reduce the chance of contact lens complications

Table 1: Modifiable risk factors to consider for patients to help them reduce the chance of contact lens complications

Ceasing planned or accidental overnight wear significantly lowers the risk of contact lens complications. Some patients may principally use their lenses on an extended wear basis for occupational reasons and the same benefits may no longer be present if they are currently working from home. In such situations, reverting to a daily wear schedule could be merited, but only if the patient has an appropriate care regimen and is suitably compliant in its correct use. In the same way, patients who habitually alter from daily wear to extended wear (for work or other reasons) could be advised to adopt a routine daily wear modality until normal clinical provision is available. Such changes to contact lens wearing schedules should be undertaken only after consultation between the patient and their contact lens practitioner.

Scrupulous hand hygiene along with correct use of care solutions, including multipurpose solutions with appropriate rub and rinse cleaning of reusable lenses, daily case cleaning and regular replacement of the lens case are all positive changes about which eye care professionals should remind their patients at the current time. Likewise, an important point is to counsel on the avoidance of contact with water to reduce the risk of microbial keratitis, especially Acanthamoeba keratitis.64,65 Finally, and consistent with general advice, when a patient is unwell, particularly with an upper respiratory tract infection, this is the time to cease wearing contact lenses and return to spectacles. Contact lens wear can be resumed, with a fresh pair of lenses, and, if used, a fresh contact lens case, when they feel well again.

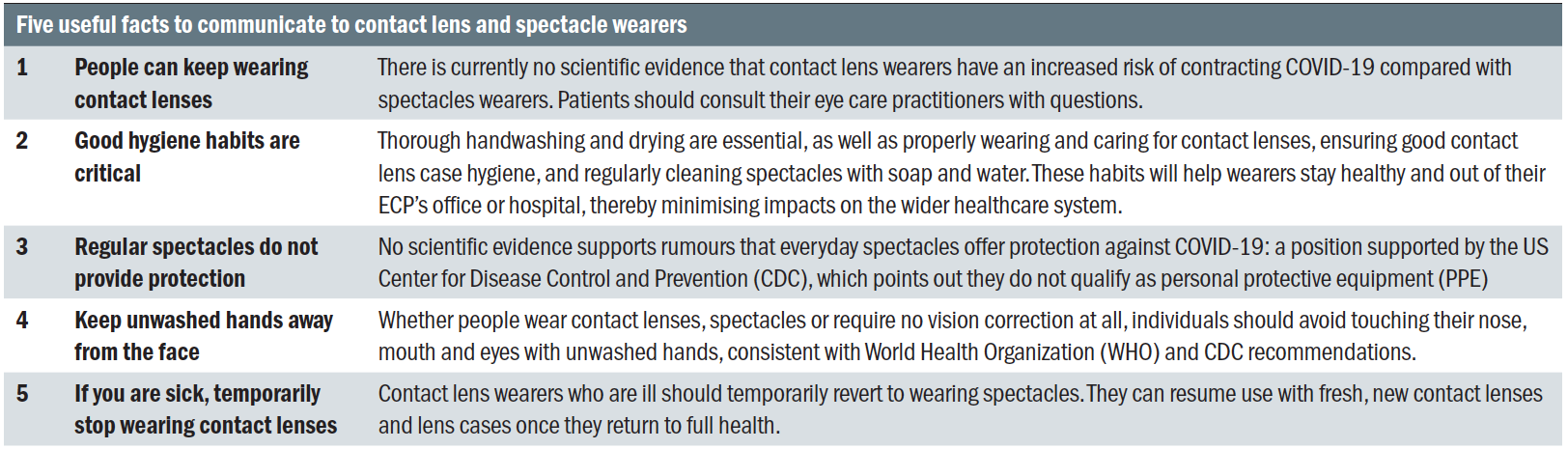

Adherence to compliant lens wear and care practices is an important aim for the profession all of the time, however, it can be argued during the current outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 this should be an area of heightened focus. The attention on thorough hand washing is welcome and an important start, but for eye care practitioners it is reasonable to use this time to go much further, revisiting patient education on safe wear and care practices with the aim of reducing the chance of developing contact lens-related complications requiring clinical care. Distilled from the evidence reviewed in the full paper,1 there are five key points that may be useful for eye care practitioners to communicate to patients (table 2).

Table 2: Information to communicate to contact lens and spectacle wearers

In addition to this, practitioners are advised to seek resources on patient-facing information to help remind them of safe wear and care practices, some of which can be found in a previous article in Contact Lens Spectrum,66 and in the UK, the BCLA has provided advice for practitioners and contact lens wearers.67 Information is also available through a number of professional organisations and contact lens manufacturers, with free downloadable content, including a handout containing the five tips related to COVID-19 and contact lens wearers, on CORE’s Contact Lens Update website.

Conclusions

In conclusion, to date no evidence suggests that contact lens wearers who are asymptomatic should cease contact lens wear due to an increased risk of developing COVID-19, advice which has been recently echoed by the CDC.68 There is no evidence that wearing prescription spectacles provides protection against SARS-CoV-2 or that any one form of contact lens material is more likely to enhance or reduce the risk of future COVID-19 infection.

Practitioners must remain vigilant about reminding contact lens wearers of the need to maintain good hand hygiene practices when handling lenses. A focus on fully compliant contact lens wear and especially on the modifiable risk factors associated with contact lens complications are important during the height of the pandemic, where access to primary and secondary optometric care may be substantially different to normal, and practitioners should act to minimise the burden on the wider healthcare system by considering their local clinical pathway options. Patients must be reminded of the need to dispose of daily disposable lenses upon removal, the need for appropriate disinfection with reusable lenses, including the use of a rub-and-rinse step where indicated and appropriate case cleaning and replacement. Finally, consistent with guidance for other types of illness, particularly those of the respiratory tract, no contact lens wearer with active COVID-19 should remain wearing their contact lenses. This is the time to cease contact lens wear and revert to spectacles.

This article was featured as a CET module in Optician. To complete the module online visit https://cet.opticianonline.net/Course/Information?courseId=5933

Lyndon Jones is Professor, School of Optometry & Vision Science and Director, Centre for Ocular Research & Education (CORE), University of Waterloo, Canada where Karen Walsh is Professional Education Team Leader and Clinical Scientist. Mark Willcox is Professor and Research Director, School of Optometry and Vision Science, UNSW, Australia. Philip Morgan is Professor of Optometry, Head of Optometry, Deputy Head of the Division of Pharmacy and Optometry, Director, Eurolens Research, The University of Manchester, UK. Jason Nichols is Associate Vice President for Research & Professor, Office of the Vice President for Research & School of Optometry, University of Alabama, USA.

Acknowledgment

Supported by an educational grant from CooperVision.

References

- Jones L, Walsh K, Willcox M, Morgan PB, Nichols J: The COVID-19 pandemic: Important considerations for contact lens practitioners. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2020; In press.

- Wu C, Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang P, Zhong W, Wang Y, Wang Q, Xu Y, Li M, Li X, Zheng M, Chen L, Li H: Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2020; In press.

- Chen Y, Guo Y, Pan Y, Zhao ZJ: Structure analysis of the receptor binding of 2019-nCoV. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020; In press.

- Seah I, Su X, Lingam G: Revisiting the dangers of the coronavirus in the ophthalmology practice. Eye (Lond) 2020; In press.

- Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D: Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol 2020; In press.

- Jun I, Anderson DE, Kang AE, Wang L-F, Rao P, Young BE, Lye DC, Agrawal R: Assessing Viral Shedding and Infectivity of Tears in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients. Ophthalmology 2020; In press.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS, China Medical Treatment Expert Group for C: Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; In press.

- Bonn D: SARS virus in tears? Lancet Infect Dis 2004; 4: 480.

- Chan WM, Yuen KS, Fan DS, Lam DS, Chan PK, Sung JJ: Tears and conjunctival scrapings for coronavirus in patients with SARS. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 968-9.

- Loon SC, Teoh SC, Oon LL, Se-Thoe SY, Ling AE, Leo YS, Leong HN: The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in tears. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 861-3.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology: Alert: Important coronavirus updates for ophthalmologists. AAO Alerts 2020; https://www.aao.org/headline/alert-important-coronavirus-context: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- Peng Y, Zhou YH: Is novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) transmitted through conjunctiva? J Med Virol 2020; In press.

- Sun C, Wang Y, Liu G, Liu Z: Role of the Eye in Transmitting Human Coronavirus: What We Know and What We Do Not Know. Preprints 2020; In press.

- Garcia-Zalisnak D, Rapuano C, Sheppard JD, Davis AR: Adenovirus Ocular Infections: Prevalence, Pathology, Pitfalls, and Practical Pointers. Eye Contact Lens 2018; 44 Suppl 1: S1-S7.

- Doyle TJ, King D, Cobb J, Miller D, Johnson B: An outbreak of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis at an outpatient ophthalmology clinic. Infect Dis Rep 2010; 2: e17.

- Yong K, Killerby M, Pan CY, Huynh T, Green NM, Wadford DA, Terashita D: Outbreak of Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis Caused by Human Adenovirus Type D53 in an Eye Care Clinic - Los Angeles County, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67: 1347-1349.

- Muller MP, Siddiqui N, Ivancic R, Wong D: Adenovirus-related epidemic keratoconjunctivitis outbreak at a hospital-affiliated ophthalmology clinic. Am J Infect Control 2018; 46: 581-583.

- Marinos E, Cabrera-Aguas M, Watson SL: Viral conjunctivitis: a retrospective study in an Australian hospital. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2019; 42: 679-684.

- Sammons JS, Graf EH, Townsend S, Hoegg CL, Smathers SA, Coffin SE, Williams K, Mitchell SL, Nawab U, Munson D, Quinn G, Binenbaum G: Outbreak of Adenovirus in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Critical Importance of Equipment Cleaning During Inpatient Ophthalmologic Examinations. Ophthalmology 2019; 126: 137-143.

- Mueller AJ, Klauss V: Main sources of infection in 145 cases of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Ger J Ophthalmol 1993; 2: 224-7.

- Habibzadeh P, Stoneman EK: The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird’s Eye View. Int J Occup Environ Med 2020; 11: 65-71.

- Wu D, Wu T, Liu Q, Yang Z: The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: what we know. Int J Infect Dis 2020; In press.

- Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, Sun C, Sylvia S, Rozelle S, Raat H, Zhou H: Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty 2020; 9: 29.

- Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN: The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun 2020; In press: 102433.

- World Health Organization: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. 2020; https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- Fonn D, Jones L: Hand hygiene is linked to microbial keratitis and corneal inflammatory events. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2019; 42: 132-135.

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ: Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 2020; In press.

- Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E: Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect 2020; 104: 246-251.

- Kowalski RP, Sundar-Raj CV, Romanowski EG, Gordon YJ: The disinfection of contact lenses contaminated with adenovirus. Am J Ophthalmol 2001; 132: 777-9.

- Heaselgrave W, Lonnen J, Kilvington S, Santodomingo-Rubido J, Mori O: The disinfection efficacy of MeniCare soft multipurpose solution against Acanthamoeba and viruses using stand-alone biocidal and regimen testing. Eye Contact Lens 2010; 36: 90-5.

- Rohrer MD, Terry MA, Bulard RA, Graves DC, Taylor EM: Microwave sterilization of hydrophilic contact lenses. Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 101: 49-57.

- Pepose JS: Contact lens disinfection to prevent transmission of viral disease. CLAO J 1988; 14: 165-8.

- Amin RM, Dean MT, Zaumetzer LE, Poiesz BJ: Virucidal efficacy of various lens cleaning and disinfecting solutions on HIV-I contaminated contact lenses. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1991; 7: 403-8.

- Lazzaro DR, Abulawi K, Hajee ME: In vitro cytotoxic effects of benzalkonium chloride on adenovirus. Eye Contact Lens 2009; 35: 329-32.

- Kuc CJ, Lebow KA: Contact Lens Solutions and Contact Lens Discomfort: Examining the Correlations Between Solution Components, Keratitis, and Contact Lens Discomfort. Eye Contact Lens 2018; 44: 355-366.

- Feldman J: How Ditching Contacts For Glasses Can

Protect You From The Coronavirus. 2020; https://www.

huffingtonpost.ca/entry/how-ditching-contacts-for-glasses-protect-coronavirus_l_5e78e283c5b6f5b7c5489e44: Accessed 24 Mar 2020. - Weiss S: Does wearing glasses help protect you against coronavirus? 2020; https://nypost.com/2020/03/10/does-wearing-glasses-help-protect-you-against-coronavirus/: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- Anon: Experts do not recommend using contact lenses for coronavirus. 2020; https://www.newsmaker.news/a/2020/03/experts-do-not-recommend-using-contact-lenses-for-coronavirus.html: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- World Health Organization: Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/ 331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Healthcare Settings. COVID-19 2020; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- Warnes SL, Little ZR, Keevil CW: Human Coronavirus 229E Remains Infectious on Common Touch Surface Materials. mBio 2015; 6: e01697-15.

- Ikonen N, Savolainen-Kopra C, Enstone JE, Kulmala I, Pasanen P, Salmela A, Salo S, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, Ruutu P, consortium P: Deposition of respiratory virus pathogens on frequently touched surfaces at airports. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18: 437.

- Ong SWX, Tan YK, Chia PY, Lee TH, Ng OT, Wong MSY, Marimuthu K: Air, Surface Environmental, and Personal Protective Equipment Contamination by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) From a Symptomatic Patient. JAMA 2020; In press.

- Macias AE, de la Torre A, Moreno-Espinosa S, Leal PE, Bourlon MT, Ruiz-Palacios GM: Controlling the novel A (H1N1) influenza virus: don’t touch your face! J Hosp Infect 2009; 73: 280-1.

- Kwok YL, Gralton J, McLaws ML: Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control 2015; 43: 112-4.

- Zeri F, Naroo SA: Contact lens practice in the time of COVID-19. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2020; In press.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology: Coronavirus eye safety. 2020; https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/coronavirus-covid19-eye-infection-pinkeye: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- General Optical Council: Joint statement and advice for eye care practitioners. 2020; https://www.optical.org/en/news_publications/Publications/joint-statement-and-guidance-on-coronavirus-covid19.cfm: Accessed 24 Mar 2020.

- American Optometric Association: Contact lens wear during COVID-19. 2020; https://www.aoa.org/contact-lens-wear-during-covid-19: Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

- Chalmers RL, Keay L, Long B, Bergenske P, Giles T, Bullimore MA: Risk factors for contact lens complications in US clinical practices. Optom Vis Sci 2010; 87: 725-35.

- Chalmers RL, Hickson-Curran SB, Keay L, Gleason WJ, Albright R: Rates of adverse events with hydrogel and silicone hydrogel daily disposable lenses in a large postmarket surveillance registry: the TEMPO Registry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015; 56: 654-63.

- Chalmers RL, Wagner H, Mitchell GL, Lam DY, Kinoshita BT, Jansen ME, Richdale K, Sorbara L, McMahon TT: Age and other risk factors for corneal infiltrative and inflammatory events in young soft contact lens wearers from the Contact Lens Assessment in Youth (CLAY) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52: 6690-6.

- Morgan PB, Efron N, Brennan NA, Hill EA, Raynor MK, Tullo AB: Risk factors for the development of corneal infiltrative events associated with contact lens wear. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46: 3136-43.

- Radford CF, Minassian D, Dart JK, Stapleton F, Verma S: Risk factors for nonulcerative contact lens complications in an ophthalmic accident and emergency department: a case-control study. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 385-92.

- Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, Naduvilath T, Dart JK, Brian G, Holden BA: The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1655-62.

- Cheng KH, Leung SL, Hoekman HW, Beekhuis WH, Mulder PG, Geerards AJ, Kijlstra A: Incidence of contact-lens-associated microbial keratitis and its related morbidity. Lancet 1999; 354: 181-5.

- Dart JK, Radford CF, Minassian D, Verma S, Stapleton F: Risk factors for microbial keratitis with contemporary contact lenses: a case-control study. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 1647-54, 1654 e1-3.

- Schein OD, McNally JJ, Katz J, Chalmers RL, Tielsch JM, Alfonso E, Bullimore M, O’Day D, Shovlin J: The incidence of microbial keratitis among wearers of a 30-day silicone hydrogel extended-wear contact lens. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 2172-9.

- Morgan PB, Efron N, Hill EA, Raynor MK, Whiting MA, Tullo AB: Incidence of keratitis of varying severity among contact lens wearers. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89: 430-6.

- Steele KR, Szczotka-Flynn L: Epidemiology of contact lens-induced infiltrates: an updated review. Clin Exp Optom 2017; 100: 473-481.

- Stapleton F, Edwards K, Keay L, Naduvilath T, Dart JK, Brian G, Holden B: Risk factors for moderate and severe microbial keratitis in daily wear contact lens users. Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 1516-21.

- Arshad M, Carnt N, Tan J, Ekkeshis I, Stapleton F: Water Exposure and the Risk of Contact Lens-Related Disease. Cornea 2019; 38: 791-797.

- Stapleton F, Naduvilath T, Keay L, Radford C, Dart J, Edwards K, Carnt N, Minassian D, Holden B: Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis in daily disposable contact lens wear. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0181343.

- Carnt N, Hoffman JM, Verma S, Hau S, Radford CF, Minassian DC, Dart JKG: Acanthamoeba keratitis: confirmation of the UK outbreak and a prospective case-control study identifying contributing risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol 2018; 102: 1621-1628.

- Randag AC, van Rooij J, van Goor AT, Verkerk S, Wisse RPL, Saelens IEY, Stoutenbeek R, van Dooren BTH, Cheng YYY, Eggink CA: The rising incidence of Acanthamoeba keratitis: A 7-year nationwide survey and clinical assessment of risk factors and functional outcomes. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0222092.

- Walsh K, Lenz Y, Behrens R: Get the support you need: Freely available information can complement basic contact lens practice. Contact Lens Spectrum 2019; 34: 32-37.

- British Contact Lens Association: Contact Lens Wear and coronavirus (COVID-19) guidance. 2020; https://bcla.org.uk/common/Uploaded%20files/Fact%20sheets/BCLA%20Covid%2019%20Statement%20ECP%20Final%2013%20March%202020.pdf: Accessed 7 Apr 2020.

- Centers for Disease and Control Prevention, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html#How-to-Protect-Yourself Accessed 9 April 2020