Five years ago, following a winter that saw more people suffer from influenza due to an apparent genetic ‘drift’ in the A(H3N2) virus in addition to the usual rounds of sickness bugs we see most winters, this author wrote a CET article on hand hygiene.1 In light of the pandemic of a novel, mutated strain of the SARS coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2) and its associated disease COVID-19, it seemed appropriate to reprise and update the piece for the current times.

It feels as though the world has finally woken up to the importance of good and proper hand hygiene. Handwashing has long been identified as the most effective way of preventing the transmission of disease. But what is best practice and what are the best products to use? This article will review the various products available for the washing of hands and poses the question as to whether the prevalent use of bottles of ‘domestic’ liquid soaps in optical practice is appropriate in a clinical setting?

SARS-CoV-2

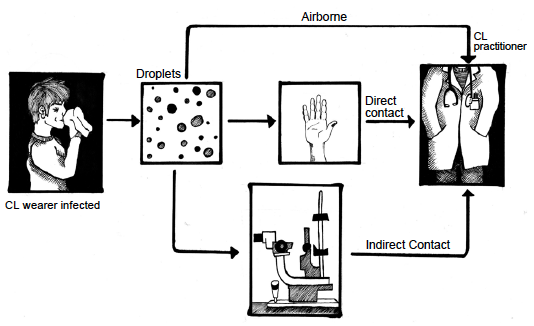

According to the latest information on the web sites of the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the virus is thought to spread mainly from person-to-person via respiratory droplets transmission by sneezing, coughing, or exhaling. Figure 1 shows how droplets can make contact another person, via the nose, mouth, eyes, or upper respiratory tract, through three main important routes:

- Airborne transmission; in case of close contact between people (within about 1.8m)

- Direct contact transmission; as when two people shake hands

- Indirect contact transmission; where an infected person touches a surface that is then touched by the second person. This latter route is due to the fact that the SARS-CoV-2 (as other coronaviruses) can survive for up to 72 hours on communal surfaces, such as handles and rails.2

Of particular concern for ophthalmic practitioners is that SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in the tears and conjunctival secretions in COVID-19 patients, and we need to be aware of the chance of transmission by aerosol contact with the conjunctiva.2

Figure 1: The main routes for droplet infection transmission (adapted from Otter et al14 by Kitty Harvey)

Figure 1: The main routes for droplet infection transmission (adapted from Otter et al14 by Kitty Harvey)

Infection control in optometry in the time of Covid-19

The current pandemic is a timely reminder of the need for

good hygiene practices in all walks of life and especially in

optometric practice where a great deal of time is spent with patients/customers in relatively confined spaces. This is especially true in contact lens practice where contact with the patient via the eyelids, as well as the tears during insertion and removal, is essential to a thorough examination. Ultimately the opportunity for cross contamination is a common danger that all practitioners and patients need to be aware of and develop strategies to avoid.

In optometric practice, infection may be transmitted from patient to staff, staff to patients, patient to patient and staff to staff by direct contact, aerosol formation or contamination of equipment or instruments in the practice.3 Interestingly there are currently no evidence-based studies directly linked with optometry to support the recommended guidelines set out by the College of Optometrists and the Association of British Dispensing Opticians. For that matter, there is no real evidence supporting cross infection as a result of a patient’s visiting high street optometric practice. Instead, these guidelines are based on expert opinion rather than conclusive evidence of efficacy in primary care.

There is also an apparent lack of research into good hand hygiene practice in a primary and community care setting, optometric practice included. Regardless, all eye care professionals delivering ophthalmic services need to be aware of infection control procedures designed to minimize cross infection. Of course, all optical employers should be mindful that the Health and Safety at Work Act (1974) ‘requires employers to ensure, so far as is reasonably practical, the health, safety and welfare at work of all employees.’

It is also worth bearing in mind that the scope of optometric practice has expanded in recent years, so that optometrists may now be involved in the therapeutic management of patients, some of whom may have infectious conditions such as conjunctivitis. Some of the procedures that are used for these patients require more rigorous attention to infection control than was previously necessary.

We also know that SARS-CoV-2 is much more infectious than regular influenza or even the previous SARS-CoV-1 virus. The

estimation now is that any person infected with this virus may infect three other people, which leads to an exponential growth of the epidemic. That was not the case with SARS-CoV-1 or previous winter influenza. It is also clear that people without symptoms can spread the virus, and it can be transmitted indirectly via contact with contaminated surfaces. So, it is something of a ‘no brainer’ that we need to be more vigilant and follow hygiene protocols with increased diligence.

There are five main areas of actions applicable in practice to minimise the transmission of COVID-19: patient management; personal protective equipment; disinfection of equipment and any contact lens trial sets; hands sanitisation; practitioner and staff monitoring.2 This article is focused on one of those five – hand sanitisation.

Handwashing in optometric practice

Handwashing is considered to be the most important measure in preventing the spread of infection in the healthcare setting.3,4 The prevalence of infection decreases as hand hygiene is improved.5,6

The aim of handwashing is to remove transient flora that colonise the superficial layers of the skin, which are most frequently linked with healthcare associated infections. Handwashing must be performed before and after significant contact with any patient and after activities likely to cause contamination; for example, handling food, handling cash, emptying wastepaper baskets, going to the toilet, blowing one’s nose.3 When seeing patients, optometrists must avoid touching their own face, nose, mouth and eyes. It is also good practice for all staff to wash hands after handling patients’ frames or after undertaking a spectacle frame adjustment. It is very important to do this before eating.

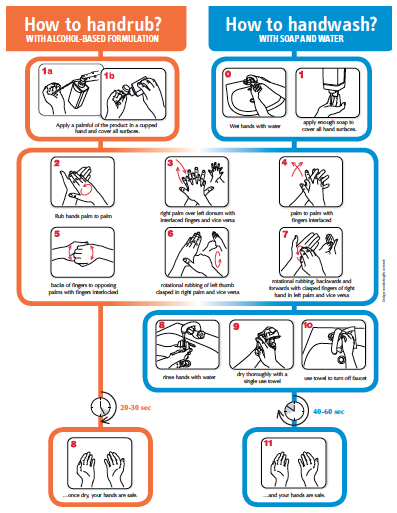

Hand basins should be fitted in all consulting rooms and locations where contact lenses may be inserted or removed and must be kept clean. In an ideal world, elbow or foot controls are recommended to regulate the flow of water. If not available, it is often recommended to operate the taps after handwashing using a paper towel to act as a protective barrier. Recommended handwashing procedures are presented in table 1.

Table 1: Recommended procedures for hand washing

Table 1: Recommended procedures for hand washing

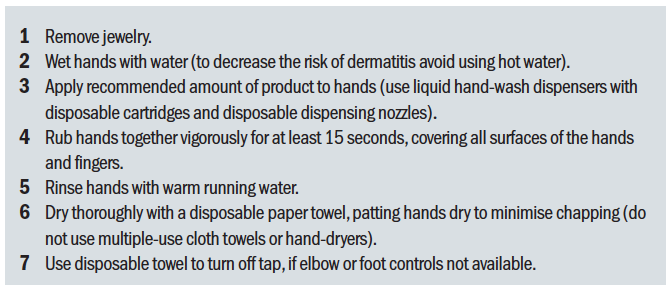

One important part of using hand wash is that staff remember to wash their hands thoroughly. Too many people wash their palms and fingers only, completely forgetting that they need to cover their thumbs (something that, in the authors view, the recent campaign has not focused enough on) and the gaps in between their fingers (figure 2). If these areas are not covered then the hand wash will have had no effect, with potential pathogens still being carried on the hands. Additionally, the time taken over the process is important. Recently, the NHS updated its advice from the time needed to sing Happy Birthday once to twice, approximately 20 seconds.

Figure 2: (a) Washing the thumb; (b) Washing between fingers

Figure 2: (a) Washing the thumb; (b) Washing between fingers

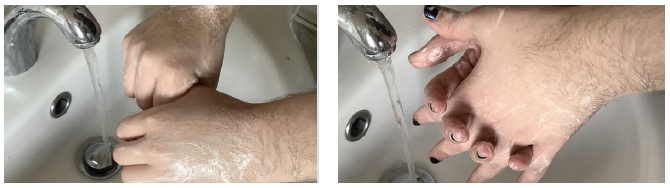

The World Health Organisation (2009) has extended recommendations on hand hygiene and produced a poster detailing the technique for use with hand sanitisers and the handwashing technique for use with soap and water (figure 3).

Figure 3: WHO recommended guidance for handwashing

Paper towels

It is highly recommended that eye care businesses provide paper towels and avoid using reusable hand towels which can easily spread pathogens. Placing reminder signs over the sink in the washing area as a constant reminder, to both patients and staff, is particularly useful. It is important for patients to witness their clinician washing his or her hands before dealing with them. In addition to washing their hands, clinicians should also cover any cuts or abrasions on their skin with waterproof plasters, again so as to reduce the risk of infection.3,4

It might seem counterintuitive, but a review paper published in 2012 concluded that, from a hygiene standpoint, ‘paper towels are superior to air dryers.’7 This is because the towels dry your hands more quickly and more thoroughly than dryers do, and contamination happens more through wet hands than dry.

Water vs waterless

In areas of the practice with no ready access to water, or where constantly popping out the back to wash hands is impractical, then the use of a hand sanitiser can be appropriate. However, hand sanitiser rubs/gels (which are often alcohol-based)8 have been shown to be more effective at encouraging healthcare workers to clean their hands between patients, despite alcohol-based formulations being poorer antimicrobials.9 However, care must be taken to remove visible soil before use, and dry skin and irritation are common with alcohol-based formulations.

Physical removal of microbes

It should also be remembered that rubbing and rinsing has a mechanical effect, even without any antimicrobial agents present. As such, in the absence of soap etc, the rubbing of hands under running water alone will likely have some effect at reducing the bioburden. However, when it comes to coronavirus, water is not good at competing with the strong, glue-like interactions between skin and virus,10 so soap is essential in a clinical setting.

Product options for effective hand hygiene

It is difficult to compare the suitability of products for hand hygiene due to differences in study methodology and design. Hand hygiene products include plain and antibacterial (liquid) soap, as well as alcohol, chlorhexidine, benzalkonium chloride and hypochlorous acid formulations. However, it should be borne in mind that other factors also influence the suitability of products. For example, some active components strip away the skin’s own natural, protective oils, causing drying which can lead to dermatitis and/or broken areas of skin if used too frequently. Cracked and damaged skin can then act to harbour harmful bacteria and also lead to a reluctance to wash hands as often as necessary.

Plain soap

Interestingly, in the original version of this article, plain soap was discouraged with the following comment: ‘Plain (non-antimicrobial) soap has minimal antimicrobial activity and is not recommended for use by healthcare workers. It can remove loosely adherent transient bacteria but can become contaminated with gram-negative bacteria.’8 However, it is interesting to note that, somewhat counterintuitively, soap is particularly effective against SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus and indeed most viruses.10 Simply put, this is because the virus is a self-assembled nanoparticle in which the weakest link is the lipid bilayer. Soap dissolves the lipid membrane and the virus becomes inactive.

Put a little more technically, most viruses consist of three key building blocks: ribonucleic acid (RNA), proteins and lipids. A virus-infected cell makes lots of these building blocks, which then spontaneously self-assemble to form the virus. Critically, there are no strong covalent bonds holding these units together, which means you do not necessarily need harsh chemicals to split those units apart. Following thorough handwashing, rinsing thoroughly is key to flushing away any virus.

While washing with water alone may have some benefit, as previously stated, it will not break the strong, glue-like interactions between the skin and the virus. Soapy water, however, contains fat-like substances known as amphiphiles, some of which are structurally very similar to the lipids in the virus membrane, and so the soap molecules ‘compete’ with the lipids in the virus membrane.10 This is, more or less, how soap also removes normal dirt from the skin. The soap not only loosens the ‘glue’ between the virus and the skin but also the Velcro-like interactions that hold the proteins, lipids and RNA in the virus together.

Anti-bacterial (liquid) soap

Anti-bacterial soap is widely available ‘over the counter’ (OTC) for domestic use. In the past, these formulations often contained triclosan (some still do), until evidence that its use is detrimental to the body’s endocrine system resulted in a ban by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017. These formulations are often only bacteriostatic, with no activity against Gram-negative bacteria and viruses.8

Alcohol-based antiseptics

Alcohol-based hand antiseptics contain isopropanol, ethanol, n-propanol or a combination of agents; they are effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi and viruses (including HSV, HIV, influenza). Hygiene experts, the NHS and Public Health England all agree that, to kill most viruses, a hand sanitizer requires at least 60% alcohol content (most contain 60-95%). It is important to note that they are not effective when hands are visibly dirty.8

Chlorhexidine

Preparations that use 4% chlorhexidine are most effective. Chlorhexidine has some residual activity on the skin,11 but allergic reactions are uncommon. Infection rates have been reported as being lower after antiseptic handwashing using chlorhexidine than after handwashing with plain soap or alcohol-based hand rinse.12 4% w/v chlorhexidine is widely used as a bacterial skin cleaner for hospital and surgical hand washing.

Benzalkonium chloride

Benzalkonium chloride (BAK) is a detergent and quaternary ammonium compound with a broad range of antimicrobial activity, including viruses such as norovirus and coronavirus. One formulation, known commercially as EcoHydra, has been shown to kill up to 99.9999% of most commonly occurring bacteria and norovirus within 15 to 30 seconds. Also, according to the manufacturer’s web site, it is effective against coronavirus. This would seem plausible as, being a detergent, BAK would compete with the lipids in the virus membrane. It is used in the relatively low concentration of 0.1%, so decreasing the possibility of skin irritation. Like chlorhexidine, it has residual activity on the skin.

Hypochlorous acid

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is a weak acid that forms when chlorine dissolves in water and partially dissociates, forming hypochlorite (ClO-). HOCl and ClO- are oxidizers and the primary disinfection agents of chlorine solutions. HOCl has a multitude of uses in wound care, dermatology, dentistry and eye care.

HOCl is an appealing disinfectant because it is an all-natural antimicrobial agent. Pure HOCl is produced as an element of the human immune response.13 During the oxidative burst, small, highly reactive molecules such as HOCl are generated as white blood cells respond to pathogens in the body. HOCl is released by neutrophils to kill microorganisms and neutralise toxins released from pathogens and inflammatory mediators.13 Because it is neutralised quickly, HOCl is non-toxic to the ocular surface.13

Although HOCl occurs naturally, it is surprisingly potent. It has broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and can kill microorganisms rapidly.13 It is highly effective in vitro against a wide range of microorganisms, including viruses. NatraSan is an example of a commercial preparation of HOCl marketed for hand sanitisation, claiming a 99.9999% bacterial kill rate.

What about gloves?

When discussing hand hygiene in the prevention of cross infection, it is reasonable to question whether it would just be better to simply wear gloves? However, assuming the use of gloves was appropriate in optometry and not a hindrance to certain aspects of practice (such as contact lens fitting), gloves must be disposed of after every patient and best practice dictates that hand hygiene measures must still take place before wearing and after their removal.4 Prolonged use of gloves may also cause skin sensitivity.4

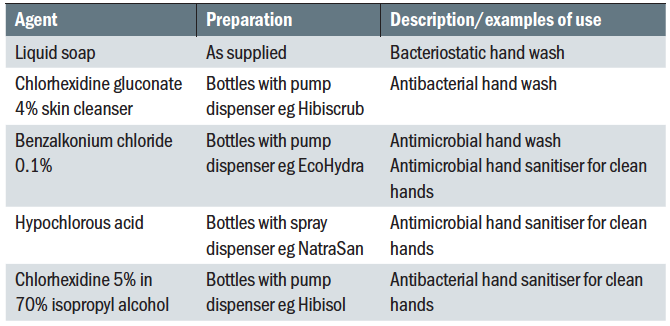

What products to use?

There are a number of considerations when selecting a product for cleaning and/or disinfection. Table 2 shows a range of product options for hand sanitisation.

Table 2: Hand sanitisation products

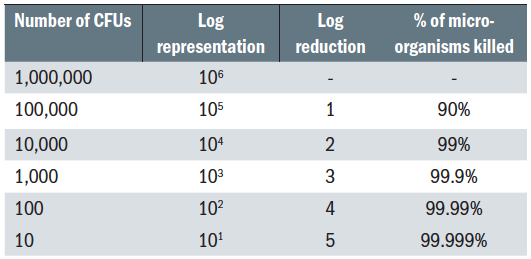

Consideration should also be given to the standard of kill rates. It is the author’s experience that most practices simply use liquid soap products purchased at a local retailer. These normally have a claimed bactericidal activity of 99.9%. These products are designed for ‘social’ or ‘domestic’ use and therefore it is reasonable to question whether something more effective should not be used in a clinical care environment. To put the efficacy of these products into perspective, practitioners need to consider microbial kill rates in the same way that they do for contact lens disinfectants.

Table 3 shows the effect of a gradual log reduction of microorganisms on survival rates. It can be seen that assuming one million colony forming units (CFU) present, a simple reduction of 99.9% is equivalent to a 3-log unit reduction leaving 1,000 CFU remaining. Using a product with a 99.9999% efficacy is equivalent to 6 log reduction, so leaving virtually no survivors. Thus, while the extra ‘0.9s’ might, at first glance, seem relatively insignificant, when put into context it may be seen that a hand wash killing up to 99.9999% of microorganisms is up to a thousand times more effective than one killing 99.9%.

Table 3: Understanding relative disinfection performance

With hand hygiene identified as the most effective way of preventing the transmission of infection (either directly or indirectly), and practices having adopted a strategy of enhanced hand washing in order to minimise cross contamination, the next question is ‘what to use?’ Having recognised that OTC liquid soaps are inappropriate in a clinical setting, what other products should be considered?

There are a number of considerations when selecting a product and, like all other areas of cleaning and disinfecting, the two key drivers are efficacy and toxicity. Ideally, a balance needs to be struck between the two. Its all very well having a highly effective broad spectrum anti-microbial that rapidly kills organisms, but if at the same time it is damaging to the skin, it will not be used as frequently as is required, so severely limiting its efficacy. Again, readers can draw on their experience of contact lens disinfectants for an analogy. Alcohol-based solutions might be compared to hydrogen peroxide, in that they are powerful anti-microbials but are also toxic to body tissue (when not neutralised). Similarly, the frequent use of alcohol-based products will dry out the skin, which can lead to dermatitis in many users. In the end, disinfectants gentler on body tissue might ultimately be more effective because regular use will be encouraged.

Modern hand hygiene products might be viewed similarly to multipurpose contact lens solutions in that they are effective, with a prolonged action but gentler on body tissue. Additionally, they may have additional agents to enhance performance such as emollients to maintain and protect the skin condition.

But how do optical professionals know which products are most effective? Well some assurance can be gained when the product is compliant with all international hand wash protocols and, in the European Union, the EU Biocidal Products Directive 98/8 EC. Additional confidence comes if it is also compliant with the 2013 EU Biocidal Products regulations and, in the UK, if it has been approved by the NHS for use in hospitals.

Conclusion

All members of the practice team should adopt thorough measures to decrease the risk of infection. This can be difficult; the nature of the job demands that the practitioner gets in close proximity to their patient, with a high potential for transmission of infection. Adopting thorough hand hygiene protocols has been shown to be the most effective strategy for avoiding the spread of infection.

While alcohol-based products contain a high-percentage alcohol solution (typically 60-80% ethanol) and can ‘kill’ viruses; soap is better because you only need a fairly small amount of soapy water, which, with rubbing, covers your entire hand easily. Whereas you need to literally soak the virus in ethanol for a brief moment, and wipes or rubbing a gel on the hands do not guarantee that you soak every corner of the skin on your hands effectively enough.

So, in the current climate with a focus on COVID-19, good old-fashioned soap is as good as it gets, however in a clinical setting and when considering pathogens other than viruses, a modern, broader spectrum product with 99.9999% efficacy is more appropriate. Ideally, this will be a handwash used with running water. However, use of a similarly broad-spectrum sanitiser is recommended when handwashing is not handy or practical, such as in retail areas. This will encourage more regular hand disinfection between dispensing/adjustments particularly when constant popping ‘out the back’ is impractical.

Practices need a clear, documented strategy to prevent cross contamination in optometric practice. All members of the practice team then need to strictly follow these basic hygiene rules, in order to help prevent cross contamination leading to infection. As well as making sense from a ‘good practice’ perspective, by helping reduce unnecessary infection among patients and staff, it also makes good business sense, by saving unnecessary time off work for staff and potential negligence claims from patients.4

Nick Atkins is Director of Marketing and Professional Services for Positive Impact.