Drugs for glucose control

It is currently estimated that, in the UK, 3.5 million people live with diabetes with the majority of cases being type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). In addition, over 590,000 people could have diabetes but are yet to be diagnosed (data available at www.diabetes.co.uk). Optometrists play an important role, not only in screening for the ocular complications of diabetes, but also in screening for evidence of the presence of diabetes itself. In addition, they can also detect and monitor possible ocular side effects of the medications that diabetic patients use to control their condition. Differentiating these side effects from the ocular symptoms that are the consequence of uncontrolled diabetes is very important.

Insulin injection treatment of diabetes

For type 1 diabetes, multiple, daily insulin injections are the main method of treatment. It is well known that patients suffering from type 1 diabetes, or those with poor glycaemic control (especially younger patients), have a higher risk of myopia than the general population.1 In addition, in historic publications, many authors have correlated the development of hyperopia or the reversal of myopia with a after rapid decrease in blood sugar levels following insulin injections.2-5 This finding is likely to result from fluctuations in hydration and dehydration of the crystalline lens. However, no recent studies have either satisfactorily confirmed or inferred these observations

It has been reported that, in certain patients, there is a risk of diabetic papillopathy (figure 1) after a rapid reduction in blood glucose following insulin injections. This occurs even if those individuals have not had any previous retinal changes before.6 In addition, an association between insulin use and diabetic retinopathy (DR) has also been reported.7  Figure 1: Diabetic papillopathy has been reported as an adverse effect of insulin use

Figure 1: Diabetic papillopathy has been reported as an adverse effect of insulin use

Such research papers are either old or based on sporadic cases. Nevertheless, if our insulin-dependent patients present with such changes, it is important to remember that, when other explanations are exhausted, their treatment could potentially play some part and so management should be modified accordingly.

Oral diabetes medication

In type 2 diabetes, diet and exercise modification is usually sufficient to control blood sugar levels. Nevertheless, there is a wide variety of anti-diabetes drugs that can be prescribed when the situation requires and without the need for recourse to insulin treatment. The decision to prescribe is based on both the safety of the drug treatment and its predicted effectiveness, as well as patient tolerance of the drug, any relevant comorbidity, and potential interactions with other existing medications.8

One of the most used drugs used for treating type 2 diabetes is metformin hydrochloride. This acts by lowering both the basal and post-prandial (after eating) blood glucose concentrations. It is the first choice for initial treatment for all patients with type 2 DM and, according to NICE, also has a ‘positive effect on weight loss, reduced risk of hypoglycaemic events and the additional long-term cardiovascular benefits associated with its use.’

Metformin has few side effects. Ocular effects reported include dry eye disease9 and an increased risk of angle-closure glaucoma. However, the drug’s beneficial impact is usually considered sufficient to outweigh these possible adverse effects. Indeed, it has recently been shown that patients who had been prescribed metformin had decreased odds of developing age-related macular degeneration,10 primary open-angle glaucoma, as well as DR.11

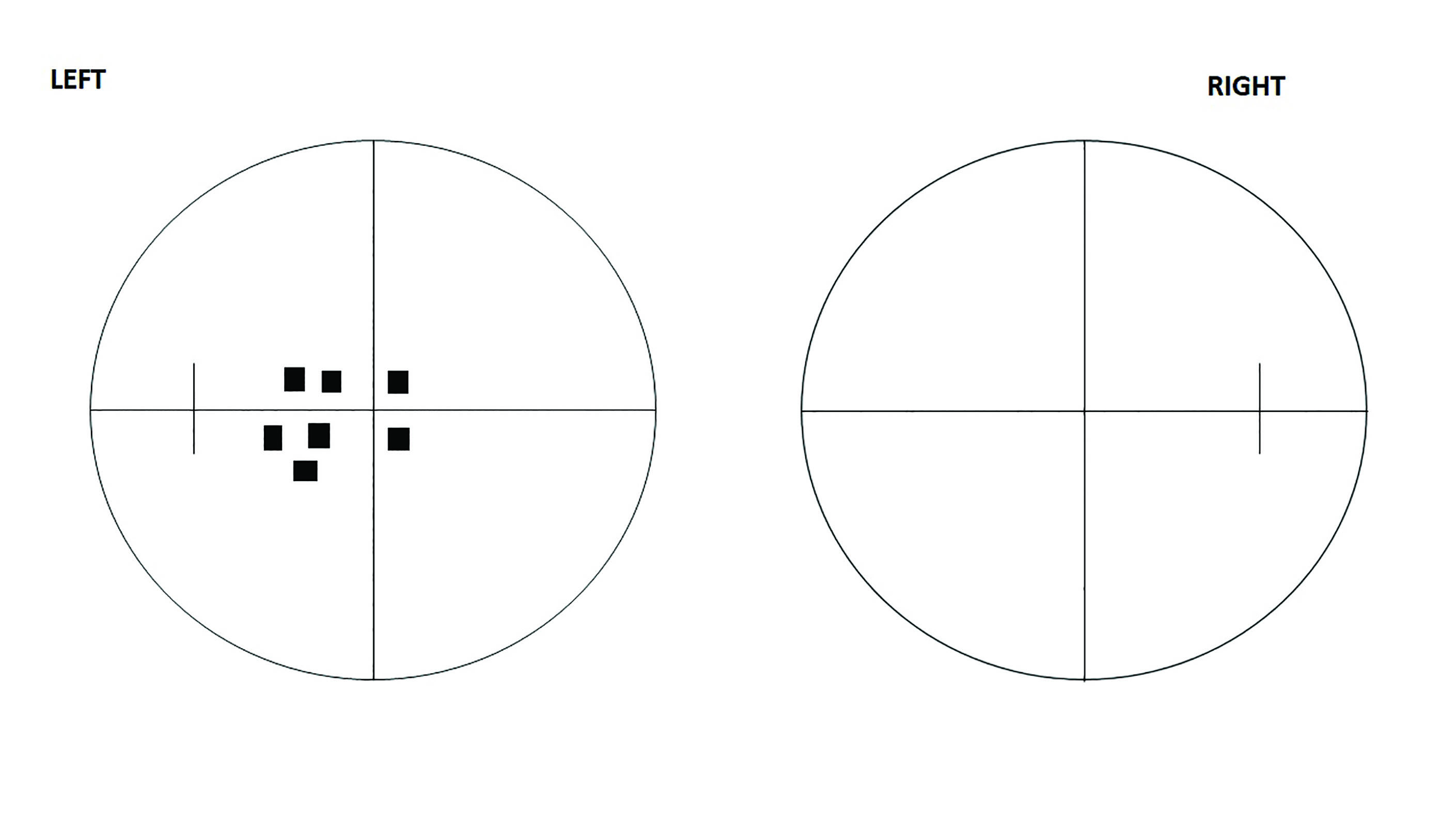

Sulphonylureas are another group of drugs used for the treatment of type 2 DM. They are potent osmotic agents and it has been reported that their use may lead to crystalline lens changes, refractive error shifts and accommodative insufficiency.12,13 Central or centrocoecal scotoma (figure 2) as well as visual loss due optic neuropathy have also been reported.14

Figure 2: Central or centrocoecal scotomas have been linked with sulphonylurea use

Figure 2: Central or centrocoecal scotomas have been linked with sulphonylurea use

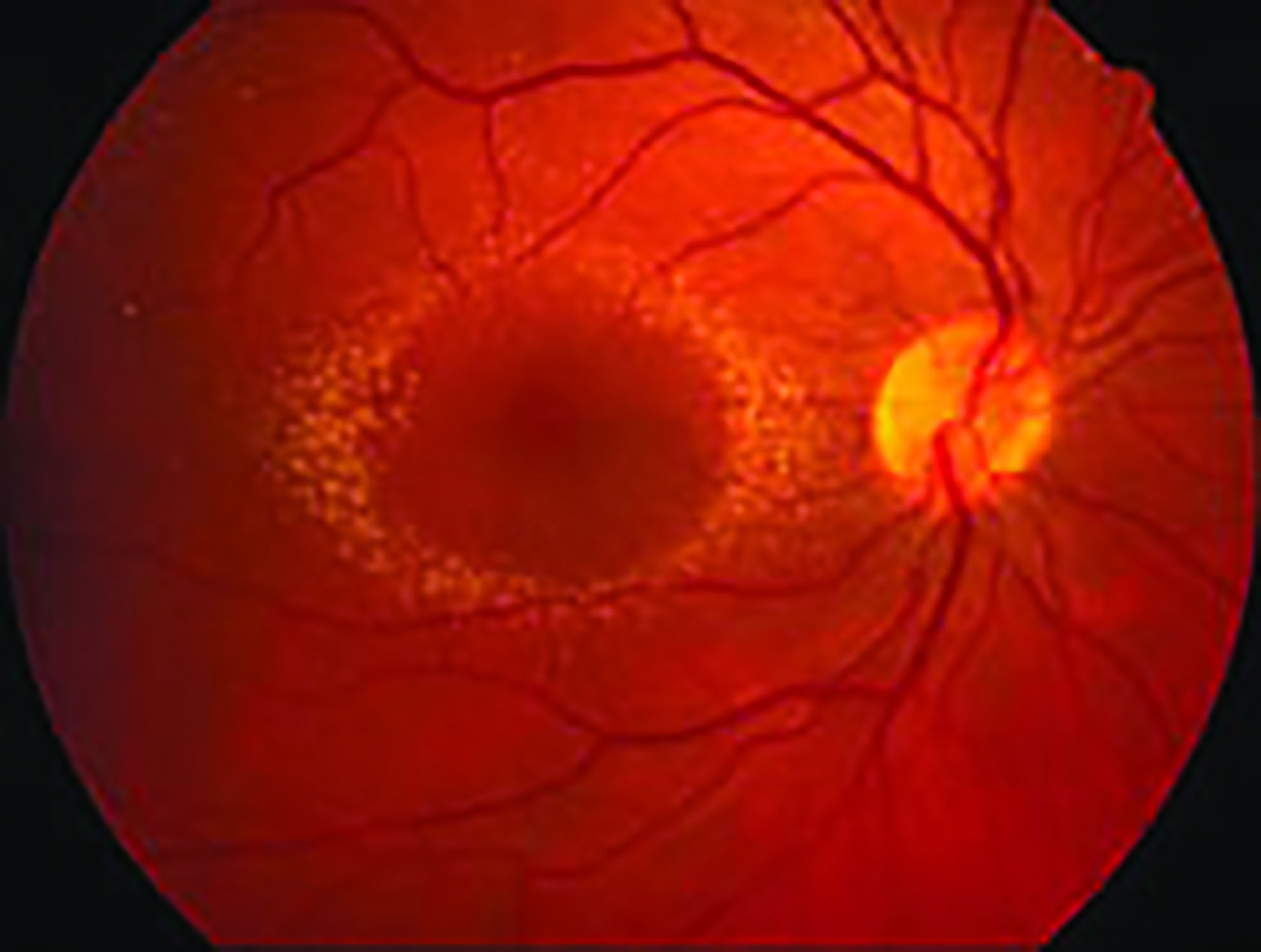

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are drugs that ameliorate both peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance and are considered to be an effective glucose-lowering treatment for patients with type 2 DM.15 They are only used as a second or third-line therapy, and are prescribed in combination with other oral agents or insulin.16 TZDs are associated with a number of systemic side effects. Ocular side effects include macular oedema (figure 3).17  Figure 3: Thiazolidinedione use has been known to cause macular oedema

Figure 3: Thiazolidinedione use has been known to cause macular oedema

Other anti-diabetes drugs (including meglitinides, gliptins, sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists) are not associated with ocular side effects.

Drugs for endocrine disorders

The endocrine system is essential for the maintenance and regulation of a wide variety of physiological functions. Any hormonal imbalance can have a profound effect on health and well-being. Drugs used to treat such diseases are readily available and very effective. Nevertheless, as with any other drugs, hormonal agents may induce side effects and some of these occur at the ocular level. The following represent the most commonly prescribed hormonal treatments that are most likely to be encountered in eyecare practices.

Treatments for thyroid disorders

Hypothyroidism represents an endocrine disorder associated with reduced secretion of thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) from the thyroid gland in the region of the neck. The condition affects the entire body and results in a large variety of symptoms. These range from fatigue, depression and muscle weakness to abnormal heart rate, impaired memory and low fertility, to mention just few. It has also been reported that hypothyroid patients may also suffer visual migraine.

Levothyroxine is the drug usually prescribed for this clinical condition. It has been reported that the long-term use of levothyroxine can lead to visual hallucinations, eyelid hyperaemia and papilloedema (pseudotumour cerebri). These adverse effects usually disappear after discontinuation of the drug.14 In addition, ocular pain, ptosis, diplopia and ophthalmoplegia have also been reported as being caused by levothyroxine use.15

Hormonal drugs

Oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and anti-oestrogen medication have all some associated ocular impact. Oral contraceptives are widely used for birth control. HRT is used to minimise problems caused by the menopause and consists of a combination of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone. Anti-oestrogen medication is used to treat advanced, metastatic breast cancer.

One of the main contraindications for the prescribing of oral contraceptives and HRT is uncontrolled hypertension. The drugs are also known to also increase blood coagulability. Because of this, oral contraceptives and HRT may cause retinal vascular complications include retinal arterial and venous occlusion and retinal thrombosis. Other ocular side effects that have been reported include:

- Dry eye (and associated contact lens intolerance)

- Corneal oedema

- Optic neuritis

- Macular oedema

- Transient ischaemic attacks

- Papilloedema (figure 4)19

Figure 4: Papilloedema has been reported as resulting from hormonal treatment

Figure 4: Papilloedema has been reported as resulting from hormonal treatment

The oral anti-oestrogen drug tamoxifen works by counteracting malignant tumour growth that has been promoted by oestrogen in hormonally-dependent breast cells. Ocular toxicity can occur after treatment with high doses of tamoxifen. Side effects can include the following:

- Pseudo cystic cavities in the macula

- Full thickness macular hole (figure 5)

- Crystalline retinopathy; yellow-white refractile bodies confined to the plexiform and nerve fibre layers, typically found in the macular and paramacular areas (figure 6)

Figure 5: Full thickness macular hole

Figure 5: Full thickness macular hole Figure 6: Crystalline maculopathy

Figure 6: Crystalline maculopathy

Therefore, all patients on tamoxifen should be monitored with baseline and subsequent annual spectral domain OCT scanning of the macula.20

Treatment for erectile dysfunction

Erectile dysfunction is most commonly treated by the drug sildenafil citrate (known most widely as Viagra) which is available from pharmacists without a prescription. The drug enhances nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation in the corpus cavernosum of the penis resulting in a maintained erection. The most common ocular complaints after taking this medicine are blurred vision and increased light sensitivity. Other reported ocular side effects include:

- Decreased colour vision (sometimes reported as a blue tinting which is called cyanopsia)

- Changes in light perception

- Transient ERG changes

- Conjunctival hyperaemia

- Ocular pain

- Mydriasis

- Retinal vascular occlusions

- Subconjunctival haemorrhages

Cases of anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (occlusion of the arterial supply to the optic nerve head) have also been reported and are seen more often in those taking higher doses. It has been reported that symptoms are usually evident around 15 to 30 minutes after taking the medication and usually peak at 60 minutes.20

Anti-rheumatic medication

Rheumatic disorders are conditions affecting the joints or connective tissue, typically causing chronic, often intermittent, pain. Many such rheumatic diseases affect not only the joints, but many other organs and systems, including the eye. Disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, ankylosing spondylitis, scleroderma and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can affect the eyes in many ways. Adverse effects are known to impact upon many ocular structures, from the lids and the cornea through to the choroid and the retina, and may have serious consequences for both normal visual function and patient well-being.21 Furthermore, many treatments for rheumatic diseases have side effects that manifest at the ocular level. Some important examples are discussed here.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are widely used in the treatment of inflammatory rheumatic disorders. Besides their systemic actions and side effects, their ocular consequences are also very well documented.22 The best known to eye care practitioners are:

- Cataract; usually posterior subcapsular (figure 7)

- Increased ocular pressure; this may lead to secondary glaucoma

Both of these complications in relation to corticosteroids have been well documented since the 1950s23 and 60s.24,25 The severity and significance of each is closely associated with the strength of dose and the duration of treatment, although some patients have presented with adverse response even with low dosage treatment. Indeed, currently we don’t know if there is a safe daily dose of corticosteroids or how long an apparently ‘safe’ dose can be maintained. Therefore, all patients under treatment with corticosteroids should be carefully monitored up to two to four times a year. In addition, symptomatic patients should receive care as soon as possible. For individuals that are glaucoma suspects, or have already been diagnosed with glaucoma, the frequency of examination and testing will be dependent upon the stage of the disease and the existence of additional risk factors (such as a strong family history of the disease).

Figure 7: Posterior subcapsular cataract due to steroid use

Figure 7: Posterior subcapsular cataract due to steroid use

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

This category of drug comprises a large number of agents that have similar action, though structurally may be very different. The most commonly used include aspirin, ibuprofen, diclofenac, indomethacin, naproxen and celecoxib. They act by reducing pain and inflammation but are also known to have a multitude of potential systemic side effects, including gastrointestinal bleeding and increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

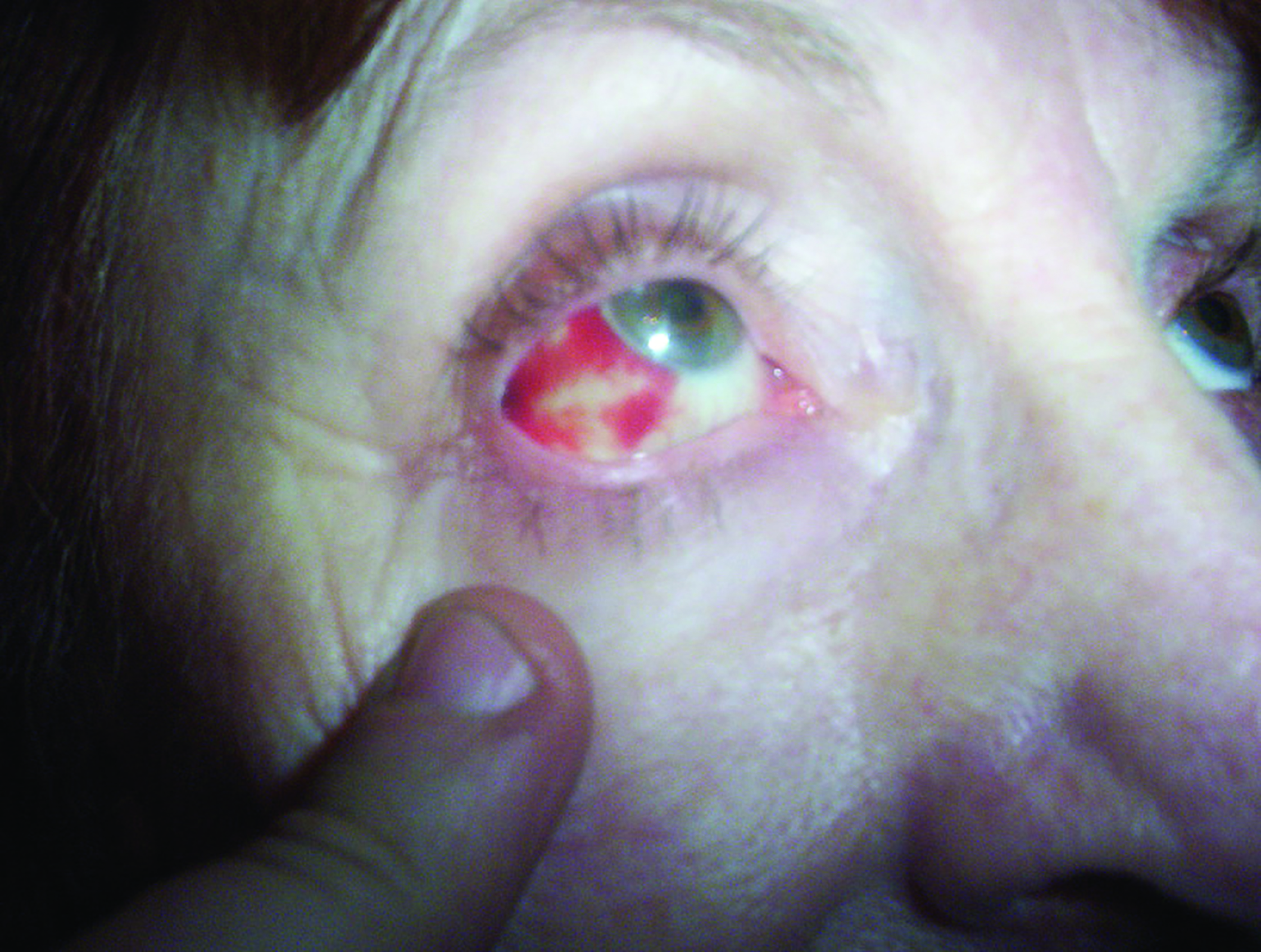

At the ocular level, there have been reports of a number of adverse effects. For example, the use of indomethacin has been associated with cases of corneal opacities, blurred vision 26 and retinopathy.27 Aspirin and ibuprofen have been linked to subconjunctival and retinal haemorrhages (figure 8) and, as such, should be avoided following any ocular surgical interventions. If any ocular changes are seen in patients under treatment with NSAIDs, treatment should be interrupted and alternatives should be considered by the prescribing clinician.

Figure 8: Subconjunctival haemorrhage has been associated with the use of aspirin and ibuprofen

Figure 8: Subconjunctival haemorrhage has been associated with the use of aspirin and ibuprofen

Hydroxychloroquine

Hydroxychloroquine is used to treat RA, SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome. It has been shown that its ocular toxicity depends on duration of treatment. After five years of use, the risk of retinal toxicity is 7.5% but this is reported to increase to 20% to 50% after 20 years. 28 The drug binds to melanin and causes retinal toxicity which manifests clinically as a bulls-eye maculopathy and associated acuity loss. Once present, this cannot be reversed.

In 2020, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth) published a collaborative recommendation for systematic retinal screening in users of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in the UK.29 Some of their key recommendations are listed below. This document has also been published by the College of Optometrists30 and, for an overview, see Optician 16.11.18.31

The recommendations from the RCOphth include the following:

- Monitoring for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy should take place in the hospital eye service

- All individuals who have taken hydroxychloroquine for more than five years should receive annual monitoring for retinopathy

- Patients with additional risk factors for retinal toxicity (impaired renal function, daily dose of hydroxychloroquine greater than 5mg/kg/day, and patients concurrently taking tamoxifen) should be screened annually before five years of treatment

- All patients planned to be on long-term therapy (five years for hydroxychloroquine and ≥ one year for chloroquine) should receive baseline examination, ideally within six months of starting treatment and definitely within the first 12 months

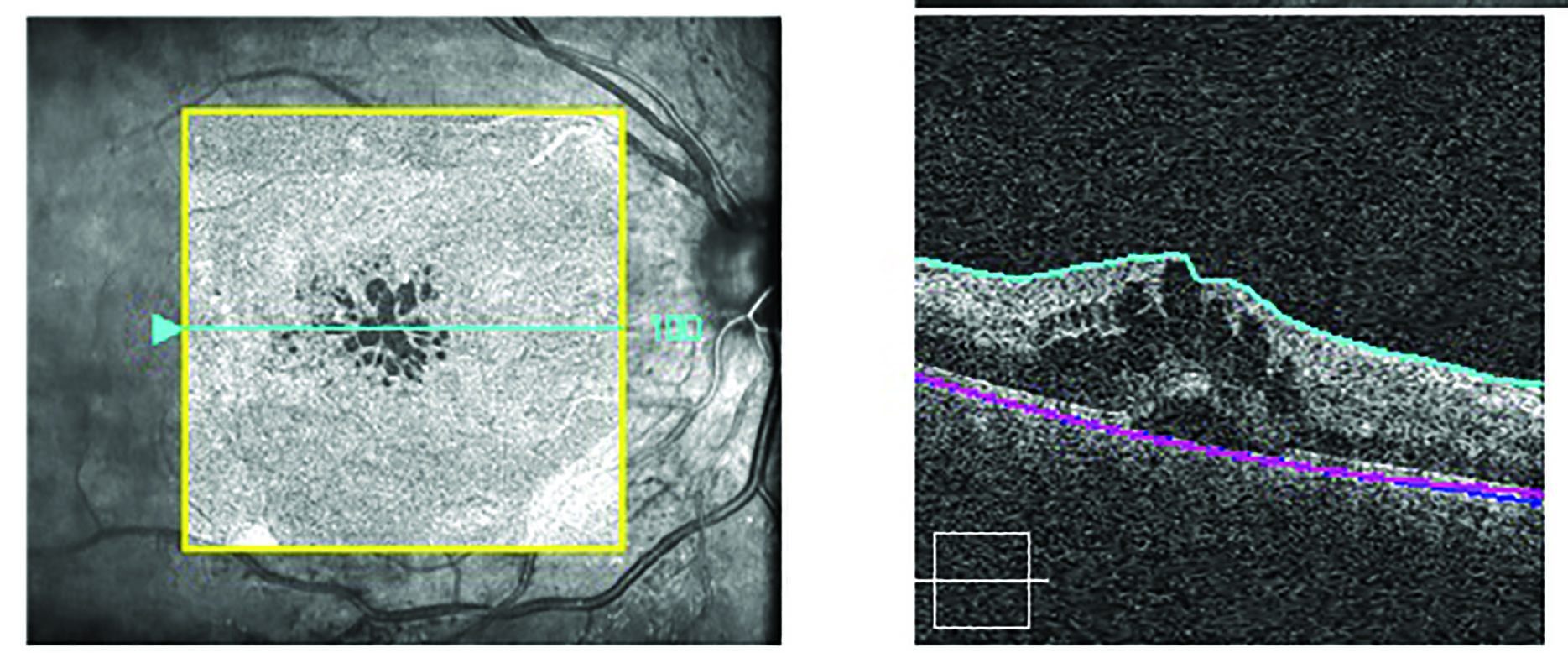

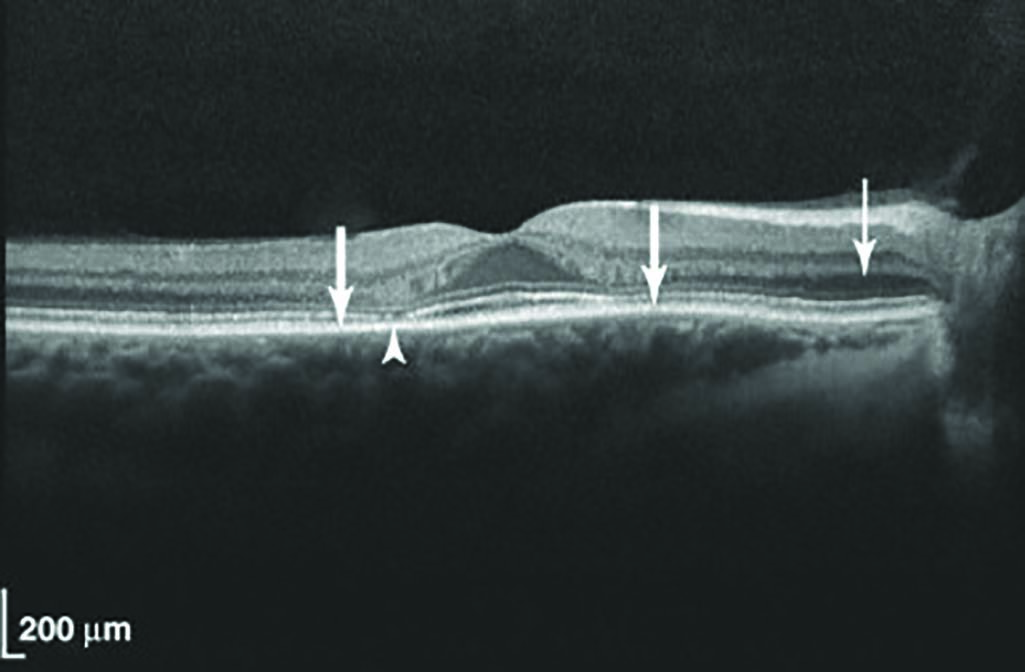

- Baseline examination should include a fundus photography and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (figure 9)

- If the baseline examination demonstrates macular pathology, a baseline Humphrey 10-2 visual field test may be undertaken

- In addition to oral communication, written information about hydroxychloroquine retinopathy and monitoring for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy should be given to all patients

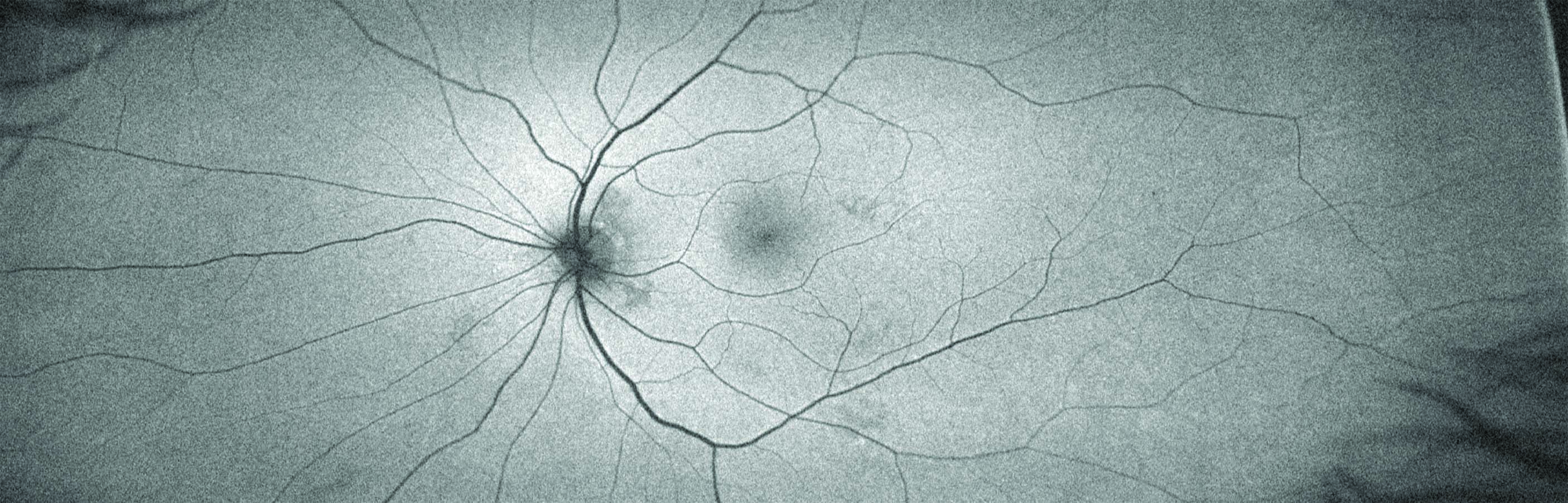

- All patients should undergo 10-2 Humphrey visual fields testing (using a white stimulus), followed by pupillary dilation and imaging with both spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and widefield fundus autofluorescence (FAF, figure 10)

- Patients with abnormalities on widefield fundus autofluorescence but with normal 10-2 visual field test results should undergo 30-2 visual field testing on another date

- Patients with persistent and significant visual field defects consistent with hydroxychloroquine retinopathy, but without evidence of structural defects on SD-OCT or FAF may be considered for multifocal electroretinography

- Monitoring for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy should be discontinued if patients stop taking hydroxychloroquine (due to retinal toxicity or for other reasons)

Figure 9: Spectral domain OCT of toxic maculopathy

Figure 9: Spectral domain OCT of toxic maculopathy Figure 10: Example of a normal wide-field autofluorescence image

Figure 10: Example of a normal wide-field autofluorescence image

With constraints upon screening within the hospital eye service and the increased availability of OCT and FAF in community optometry practice, an increased role for optometrists in chloroquine screening is currently under way. For a useful review of this area, registered optometrists can listen to an audio discussion on the DOCET website (https://docet.info/course/view.php?id=218).

Biologicals

Biologicals are a relatively recently introduced class of drugs used to treat autoimmune diseases. They include sarilumab, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept. They are used alone or in combination (with methotrexate) to treat RA. Ocular side effects have been known to occur in a minority of patients and include:

- Conjunctivitis

- Blurred vision

- Loss of visual function

- Uveitis and pan-uveitis

- Retinal microvascular abnormalities25

Other anti-rheumatic drugs

Methotrexate is an anti-metabolite and represents the ‘gold standard’ for the treatment of RA. Its reported ocular side effects include:

- Periorbital oedema

- Ocular pain

- Blurred vision

- Photophobia

- Conjunctivitis

- Blepharitis

- Decreased reflex tear secretion32

Sulfasalazine, a drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis in adults and children whose disease has not responded well to other medications, is usually well tolerated. There are, however, reports of facial nerve palsy, blurred vision and conjunctival pigmentation associated with this type of drugs.25

Dr Doina Gherghel is an academic ophthalmologist with a special interest in inter-professional learning for optometrists.

- The third part of this series will include anti-seizure agents, anxiolytics, antidepressants and other agents acting on the central nervous system.