The famous, chilling line from the 1975 blockbuster film ‘Jaws’ draws a number of parallels with the current Covid-19 crisis and emergency. Political and economic pressure, panic, mass hysteria in direct conflict with a desire for social contact and interaction. On a daily basis we face mixed cultural beliefs, attitudes and speculative theories or misconceptions and, ultimately, a lack of complete, scientific understanding at any specific moment in time.

Nobody really knows the full extent or ultimate impact of Covid-19 disease, either in the UK or globally. We do not have a crystal ball and, as yet, do not know final outcomes and the long-term impact on the eye care profession. Therefore, sensible considerations combined with realistic precautions and protective measures are paramount at a time when both professionals and patients are making tentative arrangements to re-open and re-attend clinics for non-emergency, outpatient and contact lens procedures post lockdown.

Background

The SARS epidemic (SARS meaning severe acute respiratory syndrome, a disease caused by a specific coronavirus named as SARS-CoV-1) that took hold from 2002 to 2003, with a further minor outbreak in 2004, was largely contained due to the speedy reaction of the health authorities in the Far East. Containment was further helped by a population which had a healthy cultural approach towards infection control and containment. There were 8,098 reported cases of SARS and a total number of 774 deaths recorded worldwide.1 This figure perhaps gives an indication of the much greater scale of the current global Covid-19 pandemic, caused by a different and highly contagious novel virus called SARS-CoV-2, with fatalities in the UK alone likely to exceed the total number of deaths worldwide from the 2003 outbreak.

The new coronavirus outbreak was first reported in Wuhan, China in December 20192 and, after initial spread of the disease, was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020.3 On February 11, 2020, WHO announced a name for the new coronavirus disease, Covid-19,4 and widescale lockdowns of whole populations with severe restriction of travel soon spread from the region of origin.

By the middle of March 2020, the UK finally followed the lockdown pattern of most other European countries. France, Italy and Spain had already been particularly badly affected by Covid-19 by this time. Lockdown, whether partial or complete, and voluntary social distancing (a recommended interpersonal distance of two metres is advised) has resulted in some level of control, and a reduction in the daily number of reported fatalities. The extraordinarily rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus across the globe is a clear indication of its high potential for contamination and infection. Transmission in the modern world has been facilitated by the popularity of, and affinity for global air travel, an element of globalisation that has increased dramatically since 2003.5

While the SARS-CoV-1 from 2003 seems to have been relatively well contained, SARS-CoV-2 is a more difficult beast. Patients diagnosed with the first SARS disease appeared to show visible symptoms while still contagious,1 hence an identifiable and manageable quarantine implementation plan was able to effectively contain the spread of the virus. SARS-CoV-2, on the other hand, is not only highly contagious, but may be transmitted from an infected person to another, easily and at an early stage of the Covid-19 disease, often before any symptoms have been identified. All patients, even those yet to report symptoms, should therefore be considered as potentially SARS-CoV-2 positive.6

The main symptoms confirmed for Covid-19, when they do present, are as follows:

- High temperature; the chest or back feels hot to touch on your chest or back, usually obvious enough to render measurement of temperature unnecessary.

- New, continuous cough; bouts of coughing for more than an hour, or three or more episodes in 24 hours. Patients with existing coughs report a worsening of their symptoms.

- Loss or change to your sense of smell (anosmia) or taste (ageusia); a patient suspicious of the disease may report that they cannot smell or taste anything, or that things smell or taste different to normal.

Most people with coronavirus have at least one of these symptoms.

Back to work

Questions now arise as to what measures and preparations are now considered to be the minimum requirement in a clinical setting to ensure maximum levels of patient and practitioner safety. The world is not the same place, it never will be the same again. An expectation of a return to ‘normal’, pre-Covid-19 existence is little more than a sepia-coloured flight of nostalgia and, sadly, has no place in the modern-day eye care workplace. A balance between the provision of essential and effective clinical care and the adoption of the most effective available protective procedures should be the ultimate target in implementation of any back-to-work action plan, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and a large breath shield during slit lamp examination

Figure 1: The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and a large breath shield during slit lamp examination

Factors known to increase the likelihood of cross-infection of the virus include proximity of one person to another, exposure to the virus in the environment and the level of sterility of the working environment.

Proximity

Ear, nose and throat specialists and ophthalmologists have experienced high levels of Covid-19 infection and subsequent mortality. It has been widely assumed this may be attributed to the proximity of eye care professionals to their patients during an examination. There has been some concern, and understandable anxiety, over the availability of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). Ophthalmologists were reported to have the highest rate of mortality in the original outbreak in Wuhan, China, among all healthcare workers.7

Bearing this in mind, it would seem useful to consider some of the clinical practices and procedures designed to reduce proximity with any given patient, and so to reduce potential exposure times and viral load.

Firstly, there appears to be a clear correlation between factors including the duration of exposure, the size of the room where interaction takes place, the number of personnel present, the type of ventilation or air conditioning in use, and the likelihood of cross-infection. However, up to this date, no one has yet been able to derive a definitive algorithm or accurate, predictive formula that might be applied to any specific clinical space in order to calculate risk of infection. Certainly, some of the smaller, air-conditioned consulting rooms common in community practice are likely to represent, at best, a high risk for infection. Many, for example, make it impossible to achieve the recommended interpersonal two-metre spacing for any purpose, and immediate consideration needs to be given, both to their current and their future viability.

The time during which someone is potentially exposed to viral infection, even at two-metre spacing in a clinical setting, can be minimised by the use of a validated questionnaire for history, background and symptoms. This may be undertaken prior to a visit, either by telephone or by an electronic platform (figure 2). An alternative, less attractive, option is for the patient to complete a paper questionnaire on arrival at the clinic.

Figure 2: As much information as possible is best acquired before any visit to a clinical setting takes place

Figure 2: As much information as possible is best acquired before any visit to a clinical setting takes place

Exposure at less than two metres can be streamlined by ‘bundling’ techniques, whereby all necessary ‘close proximity’ routines are completed in a collectively short space of time to reduce risk. Practitioners may like to consider re-structuring their typical clinical routines to minimise exposure at short distances. This may be assisted by basing the approach to assessment specific to all the acquired pre-test information (what tests are absolutely necessary), and perhaps by the adoption of multi-function or semi-automated instrumentation.

Reducing proximity and exposure may be particularly challenging for some appointments, such as when undertaking a complex contact lens fitting routine. Typically, this requires multiple contact lenses to be inserted and carefully observed to complete a satisfactory fitting procedure. Distancing from the patient beyond half a metre or so is impractical, as repeated physical contact and patient interactions are both necessary and inevitable. Because of this, such contact lens fitting routines for a neophyte, if considered to be non-urgent, are likely best considered for a short-term postponement.

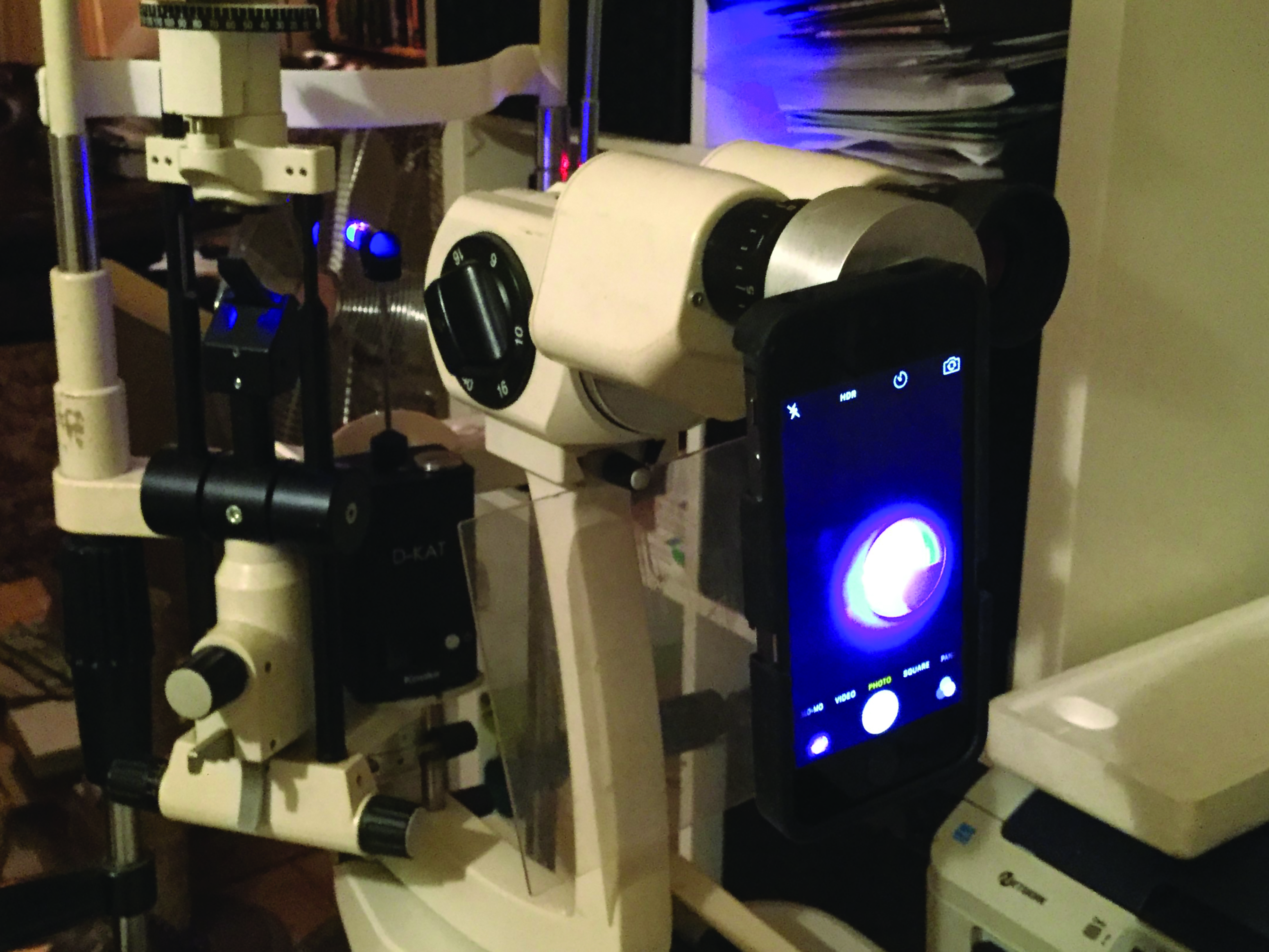

Slit lamp examination, which requires careful observation from a very close distance, is an additional proximity concern. The use of video slit lamps, which can be operated with greater separation from the patient are perhaps to be encouraged and developed (figure 3). Such instruments are widely used in teaching and presentation environments, but less commonplace in either hospital or community practice.

Figure 3: Dedicated slit-lamp imaging systems allow the practitioner to view the patient on a screen and from an increased distance

Where no integral imaging system is available, conversion of a standard slit-lamp to one with a camera viewing system is increasingly easy to undertake. A dedicated ‘lipstick’ camera is one approach, where an adaptor allows the camera to be inserted into an existing eye piece (figure 4). This is still an expensive option.

Figure 4: The Oculus ImageCam is an example of a camera designed for adding to an existing standard slit-lamp microscope viewing system

Figure 4: The Oculus ImageCam is an example of a camera designed for adding to an existing standard slit-lamp microscope viewing system

A much cheaper option might be to use a monocular, observation system, as might be used for screen viewing of the image through a standard microscope for example. Such adaptors are readily available for under £100 and might achieve a camera resolution in megapixels of double figures or more.

More recently, the cameras included in many modern smartphones have reached impressive specification, for example the Samsung Galaxy A5 (13 megapixel resolution) and the iPhone SE (seven megapixels) shown in figure 5. The higher the resolution, the lower the loss of image clarity when displayed on a larger screen or monitor. Adaptors are available to allow the accurate placement of such a device before one eye piece of a slit-lamp (figure 6), and image or video capture, either by touch screen, remote control or voice recognition, is easy to set up. The images may be viewed live on the device screen or a linked larger screen, and later may be saved or enhanced as appropriate.

Figure 5: Many commonly used smartphones have in-built cameras of impressive specification, for example the Samsung Galaxy (left) and the iPhone SE (right)

Figure 5: Many commonly used smartphones have in-built cameras of impressive specification, for example the Samsung Galaxy (left) and the iPhone SE (right)

Figure 6: Examples of smartphone adaptors for a standard slit-lamp. The one on the bottom (supplied by BondEye) is able to adapt to most hand set sizes

Also recommended, by both the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and the College of Optometrists in their latest guidelines for reducing infection risk during a slit-lamp examination, is the advice not to talk and also to add breath shields to the instrument. The exact dimensions of a protective Perspex shield for maximum effectiveness remain in some debate. The larger items (figure 1) can prohibit and restrict active physical patient interaction, while the smaller versions (figure 7) may prove to inadequate as an airborne droplet barrier.  Figure 7: A smaller breath shield fitted to a standard slit-lamp

Figure 7: A smaller breath shield fitted to a standard slit-lamp

Droplet risk

SARS-CoV-2 is an airborne virus and transmitted via droplets suspended in the air as an aerosol. Coughing or sneezing introduces a huge level of viral load. However, it has been demonstrated that verbal dialogue also increases droplet output by a significant margin. Singing has been shown to induce yet increased droplet risk, due to raised levels of exhalation. Therefore, reducing verbal dialogue to a minimum throughout the examination procedure, however difficult this may seem, is of benefit in reducing viral load, particularly so in closed, indoor, poorly ventilated

environments.

There have been some entertaining comments on various social media sites regarding the use of reduced, or zero levels of verbal dialogue when undertaking a slit lamp routine. With practice, some careful and appropriate use of body language and hand signals can achieve a successful result. Digital imaging enhances and facilitates additional success, and much of the data captured might be discussed after the examination from remote or safer distances.

Personal Protection Equipment (PPE)

The use of PPE has been the subject of considerable controversy and debate over the past few months. Public Health England has provided extensive guidance on the use of PPE in protecting from Covid-19,8 and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists has provided guidance on the use of PPE for ophthalmic staff providing hospital-based care, but which are also applicable to community practice.9

Let us consider the various forms of PPE of use to the practitioner.

Masks

The use of facial masks and their usefulness is still hotly debated as the time of going to press. There are several different categories of face mask, ranging from the simple, fluid-resistant surgical mask, through to the FFP3 and N95 respiratory masks used on Covid-19 wards. Arguably, a simple, surgical mask does not provide full protection, but certainly does provide some. Used in conjunction with a face visor (figure 8) or additional ocular protection (figure 9), a surgical mask may be considered essential PPE when exposed to any patient, with or without symptoms.

Figure 8: Simple surgical face mask with attached visor

Figure 8: Simple surgical face mask with attached visor Figure 9: A separate face shield used over a face mask

Figure 9: A separate face shield used over a face mask

Policies have differed between countries. The emergency response to Covid-19 in Hong Kong was to enforce the mandatory wearing of surgical masks for all patients in ophthalmology clinics, with practitioners wearing both masks and protective eyewear. In Italy, the recommendation was for patients to wear a mask for the duration of their visit, while maintaining good hand hygiene and social distancing. Hospital staff were required to wear a surgical mask at all times to reduce droplet spread.6

Mask wearing as a habitual behaviour can vary greatly between cultures. In the Far East, the wearing of a surgical masks is no longer considered to be out of the ordinary, whereas in the UK there appears to be a peculiarly high level of resistance to wearing them. In the absence of any contrary research or published evidence, mask wearing for both practitioner and patient should be considered essential practice. The SARS-CoV-2 virus is neither fussy nor selective regarding different cultural practices, and a ‘double masking’ preventative policy measure would represent a responsible step to take, providing both an effective obstacle to distribution and a barrier from infection. Practitioners dealing with confirmed Covid-19 patients are advised to use full FFP3 or N95 respirators.10

Gloves

Single use gloves (figure 10) are of particular interest in contact lens practice. It is debatable that any significant level of protection is provided. However, rigorous and effective handwashing may achieve a similar level of protection whilst maintaining the increased level of sensitivity required for simple contact lens routines (see Optician 17.04.2020).

Figure 10: Single use gloves

Figure 10: Single use gloves

One practical benefit of using gloves may be a reduction in the wearer’s likelihood to touch their own face. There may also be a reduced risk of contamination from hard surfaces, such as door handles, telephones and keyboards. However, in a closed, decontaminated, clinical environment, this type of risk may be considered as low anyway.

Apron

Single use waterproof aprons (figure 11) in a contact lens clinic are considered to provide protection to clothing and should be used if working at less than two metres from the patient, as would be the usual case for all slit lamp routines.11

Figure 11: Single use waterproof apron

Figure 11: Single use waterproof apron

Gown

A single use protective gown (figure 12) may be considered in the same context as an apron, but provides greater coverage and is often worn under an apron.

Figure 12: Single use protective gown

Figure 12: Single use protective gown

Visors and goggles

A range of Perspex visors are now available for facial and ocular surface protection, and can be utilised at all stages of a socially distanced or near proximity consultation. Bulky and uncomfortable if worn for lengthy periods of time, visors provide ocular surface protection from airborne droplets and allow the use of conventional spectacles or goggles in addition to the visor screen.

The visor becomes obstructive when using a slit lamp eyepiece (see figure 1), and there is a need for regular removal and so increased potential for exposure. The aforementioned adapted slit-lamp imaging options can negate, or at least limit, the need for visor removal, and this might be considered a primary consideration. Face masks can be worn in addition to visors, and so can offer additional protection.

Goggles, when allowing adequate clearance to be worn over a conventional pair of spectacles, can be considered in the same category as visors. In the event of spectacles steaming up, or becoming a hindrance underneath PPE, contact lenses should be remembered as a suitable alternative, taking all other normal hygiene practices into consideration.

Donning and Removing PPE

Everyone requiring PPE should be trained in their correct application and removal. The sequence of applying and removing PPE is well documented and can be easily sourced.12 To summarise, the best routine sequence is as follows:

Application:

- Gown (or apron)

- Mask

- Goggles (or face shield)

- Gloves

Removal:

- Gloves

- Gown

- Goggles

- Mask

- Wash hands

There are several visual guides and videos on how best to apply and remove PPE available online, or as guided and instructed by individual NHS Trusts. Ideally there should be a ‘donning’ and ‘doffing’ area, where PPE can be accessed and safely disposed (figure 13).

Figure 13: PPE is best donned and doffed in one dedicated area

Figure 13: PPE is best donned and doffed in one dedicated area

Practitioner General Wear

In order to attain, maintain and maximise hygiene levels and a contamination-free environment, best practice would be to wear short-sleeved, surgical scrub type general wear. This is certainly the recommendation for any contact lens clinic. The fabric will need the capacity to be laundered at 60˚C at every usage. At Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, all patient-facing staff have been issued with polo shirt and trousers to use as PPE. Protective clothing should ideally be laundered ‘in house’ or placed in a specific laundry bag before leaving the hospital environment.

In an ideal scenario, the practitioner would be able to shower before leaving the hospital or practice perimeter, but individual facilities (or lack of them) may prevent or limit the likelihood of this utopia. In the absence of (as yet) specific guidance, it would seem sensible for practitioners to shower immediately on return to home before interaction with other household members.

Footwear should be comfortable, lightweight and capable of withstanding disinfectant wipe on a daily basis.

Patient PPE

For higher risk consultation, a mask (simple, surgical, fluid resistant) should be issued on a patient’s arrival at a clinic and worn at all times, unless an underlying, pre-determined and recorded respiratory or psychological disorder has been identified. Gloves might be issued on patient request (see later section on hand

sanitisation).

Clinic Management

Clinic lists will need to be realistic, and additional allowance needs to be given regarding timings. This is for a number of

reasons:

- Time allowance for adequate disinfection of equipment between patients.

- Time allowance for patients to attend.

- Time allowance for patients to leave a clinical environment before next patient arrival.

- Time allowance to ensure and maintain adequate social distancing.

- Time allowance for adaptations to typical, practised, or time-established clinical routines.

- Time allowance for reassurance, appropriate guidance and management of any patient anxieties or concerns.

The authors are currently working to a clinic list of five patients per half day session. This seems sensible and manageable, and easily allows for the full implementation of all required procedures.

In a clinic managed and supported by multiple professional personnel, an available extension of working hours, with staggered start and finish times, is beneficial in reducing infection. Travel clusters and ‘rush hours’ can also be reduced by utilising a staggered, extended hours approach.

Travel

Current advice on travel in the UK is for health care professionals to avoid public transport at this moment in time, regardless of personal preference or habitual routines.13 Social distancing on public transport may be difficult, if not impossible, particularly in major city centres. Consideration of a patient’s ability to travel safely to and from an appointment has to form part of any back-to-work management programme. Remember, vulnerable, or shielded, patients may assume, correctly or incorrectly, that a scheduled hospital, or community-based appointment overrides their current lockdown or quarantine rules.

In Hong Kong, over 80% of travel is via public transport, including underground rail systems similar to those found in London. Over 95% of commuters wear face masks (figure 14), reducing risk of infection, and the Hong Kong government is in the process of issuing free, re-usable face masks to every Hong Kong resident.

Figure 14: Hong Kong city commuters on the underground rail network

Figure 14: Hong Kong city commuters on the underground rail network

In Dubai, and other countries at the time of writing, the wearing of a face mask in public is mandatory, and the nose must be fully covered. Protective gloves must be worn at all times in all indoor spaces such as shops, malls, cafés, trams. There is a hefty fine of 1,000 AED (around £225) for each breach of rule. A single person in a private car may remove the facemask, but if two or more share a car, all occupants must remain fully protected.

Patient Prioritisation

Early and realistic prioritisation can be given to a patient base. This should be dictated by perceived urgency for an intervention, individual risk factors and any known potential impact on quality of life. Typical prioritisation programmes will have high, moderate or low categories, and a RAG (red, amber, green) system of assessment can create a careful and well managed routine for the re-introduction of face-to-face clinics.14

Telephone discussion, prior to consultation, can identify any concerns or anxieties and also provide opportunity to evaluate at-risk or quarantined personnel living in the same household. Arguably, younger patients, with a lower Covid-19 risk, might be considered as appropriate for an early return to face-to-face

clinics, particularly complex contact lens clinics when one remembers rapid keratoconic progression is more probable in

the second and third decades.

Clinic Procedure

Full attention should be given to sterilising appropriately all hard surfaces prior to consultation. This must include door handles, chin rests, occluders, all open surfaces, chairs, trial frames and used trial lenses, breath shields and any other specialty equipment.15

Patients should be screened on arrival at a clinic. The assessment might include the following Covid-19 screening tests:

- Temperature check.

- Brief wellbeing, travel and health check, with attention to ascertaining any history of self-isolation, both patient and other household members.

- Hand sanitisation.

- Issue of surgical mask to be worn for duration of visit.

A one person (patient) only rule applies to the consultation room, unless there is a requirement for accompaniment, as with a young child or a vulnerable adult.

All available background routines must be completed where possible at maximum distance, or better still by remote means (see Optician 29.05.20). It is not impossible to develop and implement a hybrid, or dual, consultation programme, whereby a telephone or video consultation takes place, shortly followed by a face-to-face clinic appointment for slit lamp, topography and other ‘hands on’ fitting routines.

The patient waiting area must be clearly marked and marshalled to maintain adequate social distancing. Remember, patients may be anxious, unaware, or visually impaired, so may need additional guidance in waiting areas.

Aerosol-generating Procedures (AGP)

Irrigation following contact lens removal, mechanical lid management and exfoliation, lid eversions and epilation are all examples of variable, low level, potential AGPs, while non-contact tonometry represents a higher risk AGP. A push-up test, or perhaps digital meibomian gland expression, are variable each time, are carried out at less than one metre, and represent clear examples of low level AGPs where risk is not an easily quantifiable or measureable factor.

The risk introduced by low level AGPs does not appear to have been evaluated or fully researched, and each procedure would induce variable levels of risk linked to the duration of exposure during, frequency of, and proximity when performing any particular function.

Final thought

Remember, minimal time for exposure and maximum distancing (with appropriate PPE) reduces infection risk and offers the most successful outcome.

At the time of writing (May 19, 2020):

- UK population, approximately 60 million. Confirmed Covid-19 cases, 240,161. Fatalities, 35,341

- Hong Kong population, approximately 7.5 million. Confirmed Covid-19 cases, 1056. Fatalities, 4

‘Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water…’ Nobody has caught and killed this shark yet. •

- The authors wish to note that the Covid-19 emergency is both fluid and dynamic. All protection measures and statistics are considered to be correct at time of writing.

Nick Howard is a specialty Contact Lens Optician working in two East Lancashire NHS hospitals. He is a BCLA Fellow and current BCLA Council member and has lectured widely on complex contact lenses and ocular surface disease in the UK, Europe, Middle East and Far East.

Dr Cindy Tromans is a Consultant Optometrist and Head of Optometry Services at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, where she specialises in complex and therapeutic contact lenses and emergency eye care. She is also President of the European Council of Optometry and Optics and a Director of the World Council of Optometry.

References

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/sars

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine, 2020; 382: 727–733

- https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

- https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/564717/airline-industry-passenger-traffic-globally/

- Lai THT et al. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: an experience from Hong Kong. Graefe’s Archives of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-020-04641-8

- Cheng-Wei Lu et al. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. The Lancet (2020); https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe

- https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/NEW-PPE-RCOphth-guidance-PHE-compliant-WEB-COPY-030420-FINAL.pdf.

- Naveed, H., Scantling-Birch, Y., Lee, H. et al. Controversies regarding mask usage in ophthalmic units in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eye (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0892-2

- https://www.college-optometrists.org/the-college/media-hub/news-listing/new-guidance-on-personal-protective-equipment-ppe.html

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/877658/Quick_guide_to_donning_doffing_standard_PPE_health_and_social_care_poster__.pdf

- https://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-safer-travel-guidance-for-passengers#public-transport

- https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Reopening-and-redeveloping-ophthalmology-services-during-Covid-recovery-Interim-guidance-1.pdf

- https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/advice-for-workplace-clean-19-03-2020