With a sight testing and spectacle dispensing programme in all special schools in England soon to be introduced in the NHS 10 year plan, and with calls for community eye care pathways for children with learning disabilities in mainstream schools, clinicians need to be comfortable and confident with the ocular and visual assessment of children with learning disabilities.

Both rewarding and challenging, the key to performing an eye examination, or indeed any health check for children and young people with learning disabilities, is to engage with them. The level of engagement is highly dependent on the approach taken, the time of day and the environmental setting. Involvement of the parents, teachers and carers all add invaluable contributions.

Hitherto, limited access to community optometrists has helped to reinforce a common misconception, among many parents

and carers of children with learning disabilities, that an eye examination requires a child to remain seated, be able to read letters, articulate symptoms well and respond to complex questions.1-3 Expectations of bright lights, eye drops and the close physical proximity of a person unfamiliar to the child likely result in poor uptake of GOS eye examinations and access to necessary eye care.

Children attending special schools and colleges will have complex or high care needs. As a result, they have a multi-disciplinary team of people around them. As well as teachers and teaching assistants, the multi-disciplinary team working in special schools include the following:

- Qualified teachers of the visual impaired (QTVIs)

- Speech and language therapists (SaLTs)

- Physiotherapists

- Occupational therapists (OTs)

- School nurses

- Paediatricians

- Social workers

Alongside the professionals are the child’s parents and carers who hold expert knowledge about their child. Learning from parents, carers and the team that support each child is vital to understand their communication needs. For example, children that are non-verbal may be able to understand what is being said, but may require more time to process and respond to any information or instruction given to them.

This article, following on from part 1 which focused on the epidemiology of learning disabilities and their ocular associations (Optician 12.06.20), will offer practical advice and strategies on how to successfully engage children with learning disabilities to assess their eye health and vision needs. Importantly, visual related problems may have been missed by all the other carers and professionals, highlighting the key role eye health professionals have as part of a multidisciplinary team of professionals looking after children with learning disabilities. This insight, and the exchange of information between the health, social work and educational services, could transform a child’s development, mobility and learning during the neuroplasticity period of the visual system.

Legal obligations

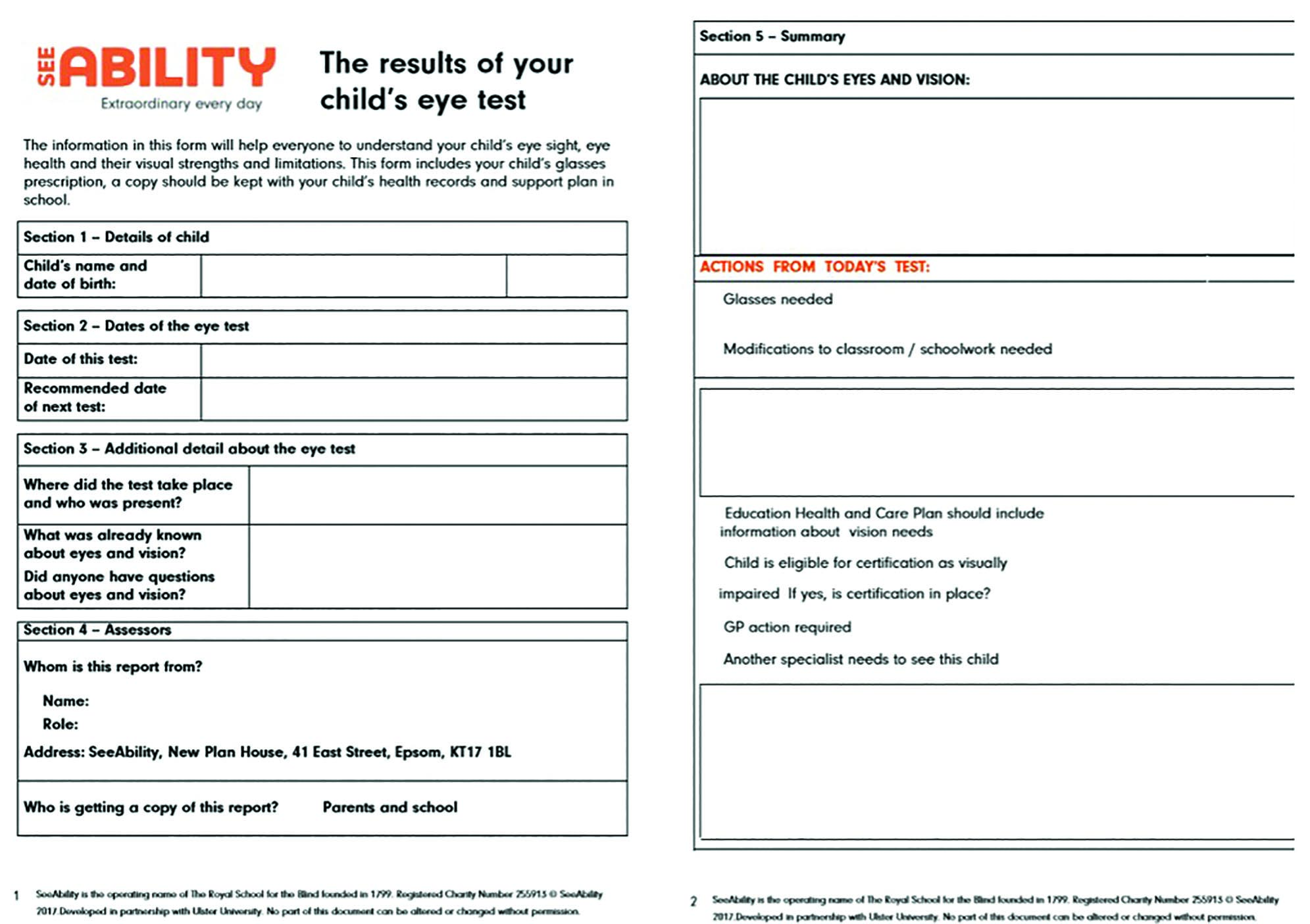

The Accessible Information Standards 20164 sets out a statutory obligation to identify, flag and meet all communication needs which relate to a disability, impairment or sensory loss and must be met by all NHS providers. Additionally, under the Equality Act 2010,5 there is a legal obligation for practices to be as accessible and effective for disabled people as they would be for people without disabilities. SeeAbility has developed a range of easy read factsheets,6 as well as an easy read pre-test questionnaire7 and a ‘results of the eye test’ feedback form.8

Planning an eye exam

Pre-assessment

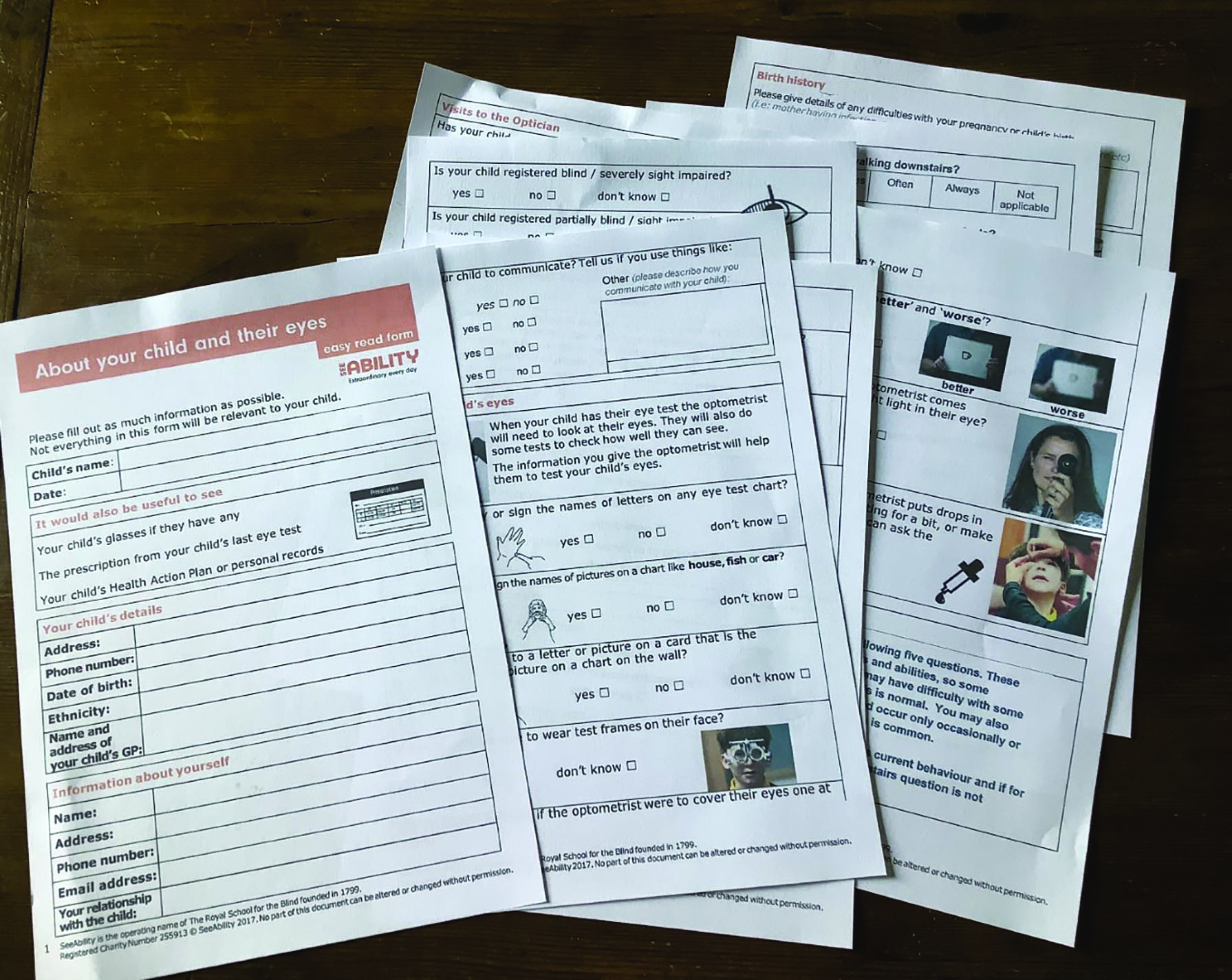

The value of a pre-assessment questionnaire, to understand the general health diagnosis and its systemic and ophthalmic impact, cannot be overstated. The SeeAbility Special Schools Project developed the ‘About My Eyes’ pre-assessment questionnaire (figure 1) which may be sent to parents and carers in advance of an assessment. Its key aims are to help to understand parents’ concerns about vision or eye health assessments, and to ascertain a child’s previous ophthalmic history, whether within the Hospital Eye Service or community optometry. Parents are asked to state any concerns about their child’s vision or visual behaviour and answer broader health and birth history-related questions to contextualise such concerns.

Figure 1a: The pre-assessment questionnaire ‘About your child and their eyes’ seeks to understand concerns about vision, the most effective communication strategies

Figure 1b: Screens for cerebral visual impairment

Figure 1b: Screens for cerebral visual impairment

The form asks about how the child communicates and illustrates (with photographs) possible elements of an eye exam, asking parents to report if they feel their child will ‘be okay’ with them. This includes such potential flash points as the optometrist coming close, wearing a trial frame, or having drops instilled. Understanding as much as possible about a child’s behaviour and the most effective communication strategies are fundamental.

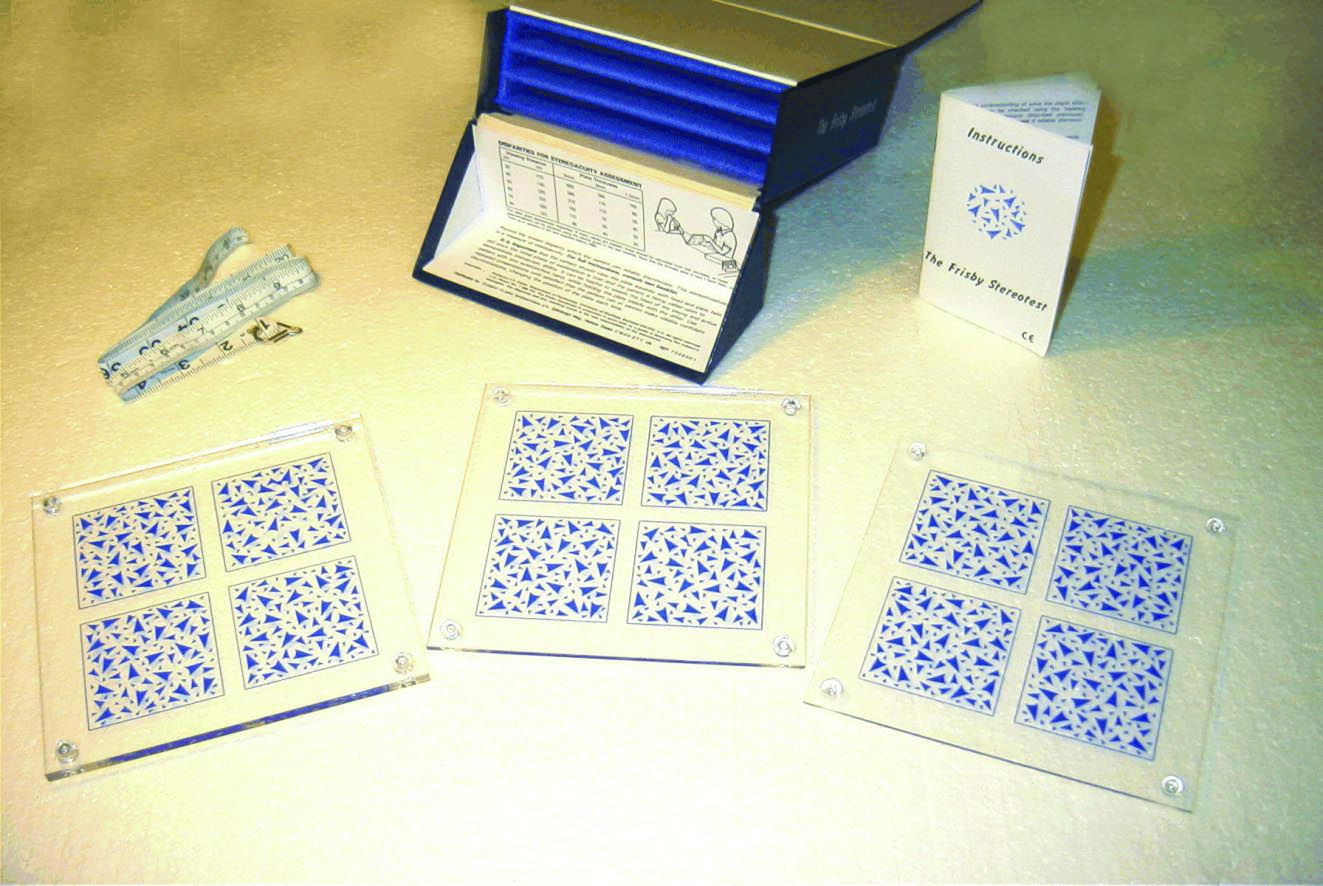

The form is also used to screen children for possible cerebral visual impairment (CVI) by asking five screening questions.9 Where CVI is suspected, further investigation or referral for further investigation can then be initiated.

The functional visual assessment (FVA) tool is a form designed to be used by parents, carers and learning disability professionals who know well the child with learning disabilities.10 It uses a series of observational questions to build a picture of visual function. Conducting this before the optometric test may be useful as a starting point, and introduces the child to a degree of visual assessment with a familiar carer or teacher. Observations from the FVA can be shared with the optometrist and serve as a starting point to further visual assessment.

Equipment

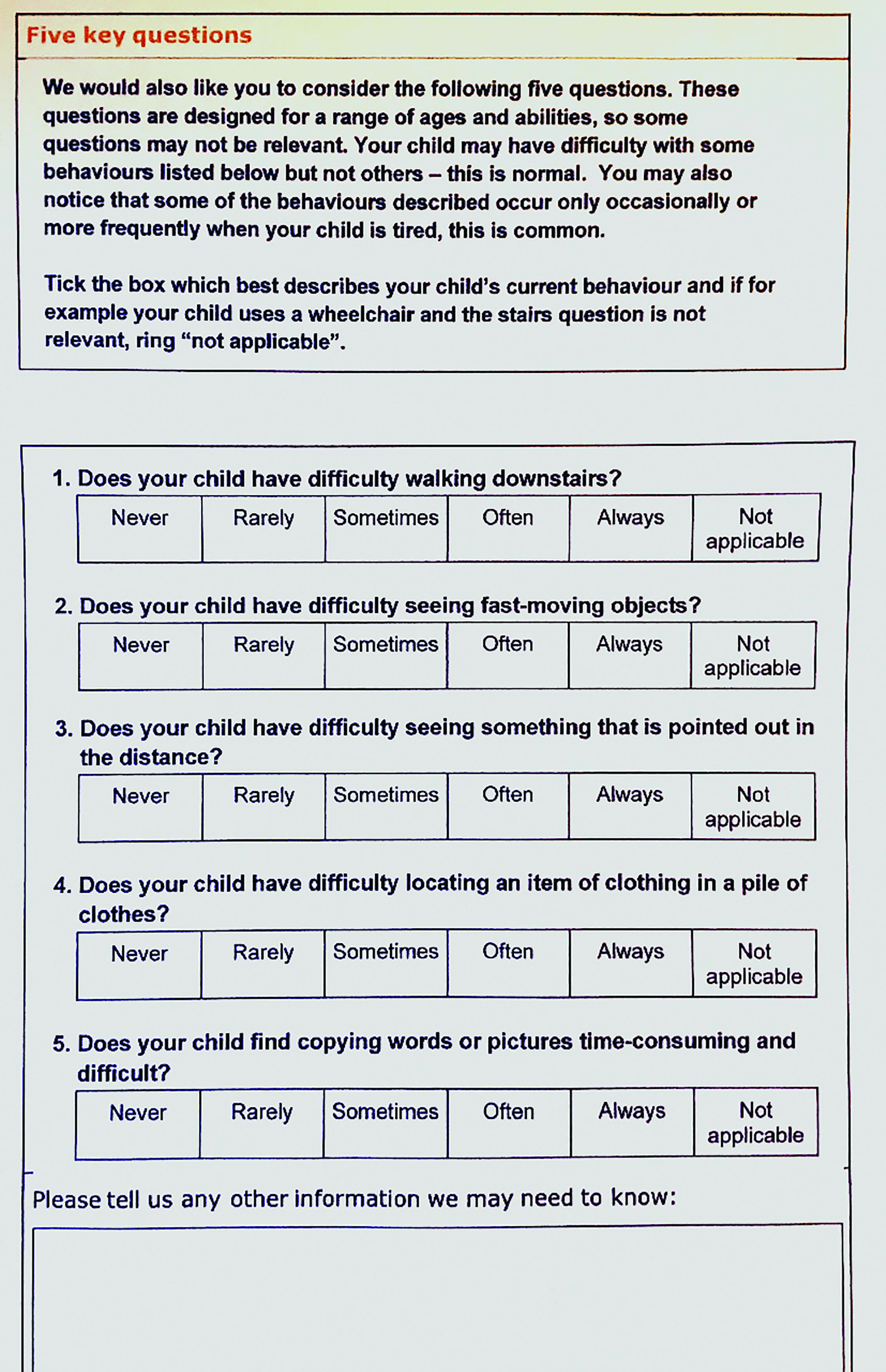

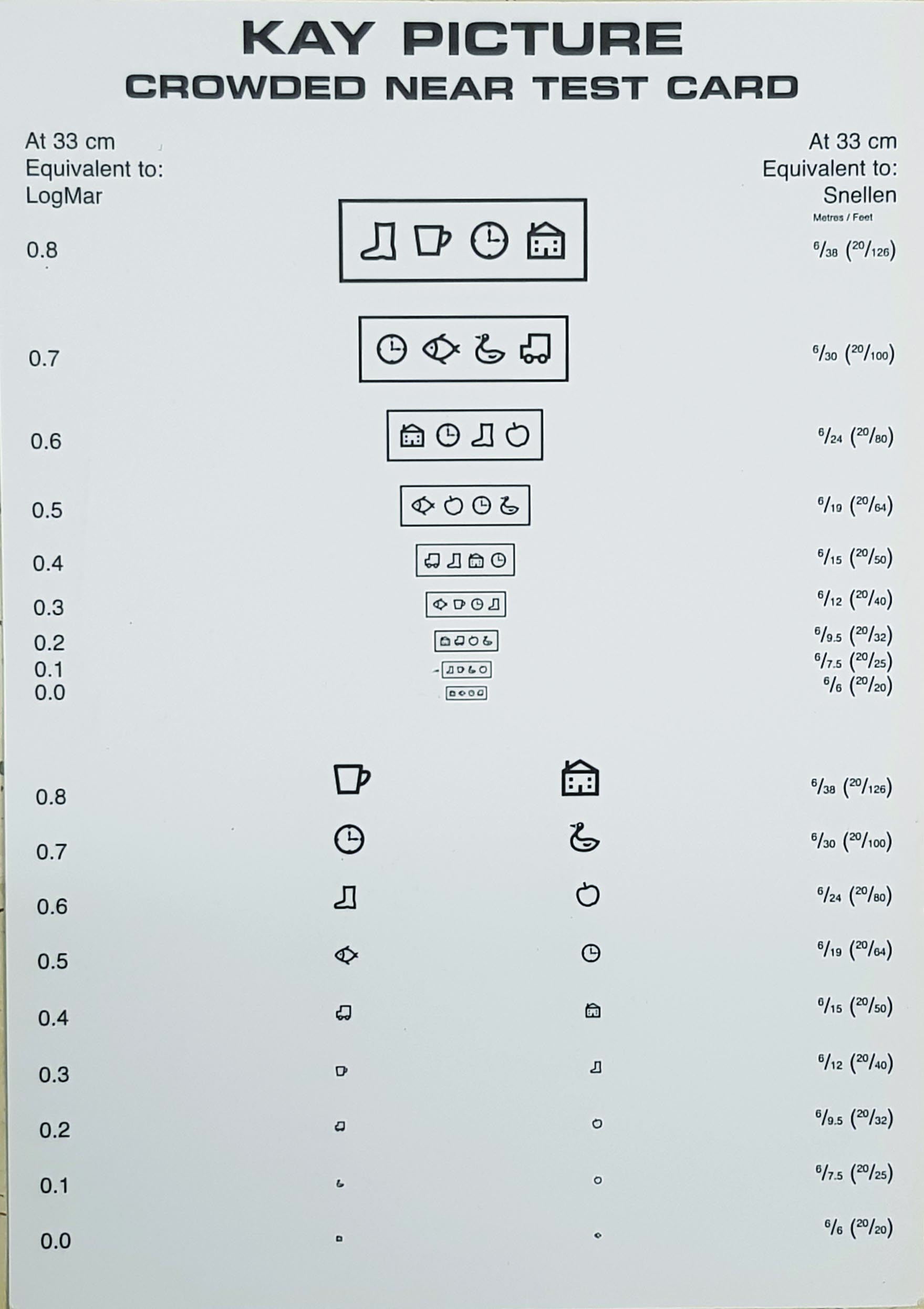

Assessing children with learning disabilities requires a flexible approach. A list of equipment can be found in the appendices of the Framework for Provision of Eye Care in Special Schools.3 A range of clinical tests together with an array of visually engaging, colourful, illuminated toys of different sizes are really helpful for fast clinical observations and to hold a child’s attention. Tablet based apps with games engaging a child to track or trace visual stimuli can be very useful together with the clinically validated tablet-based tests, such as the iSight Crowded Kay Picture Test Ltd 11(figure 2) and Peekaboo Vision Test.12

Figure 2: The iSight Crowded Kay Picture Test Ltd

A pivotal piece of new equipment that cannot be praised enough and has changed the course of innumerable assessments is the Bradford Visual Function Box (BVFB, see figure 4), developed by consultant ophthalmologist Rachel Pilling. It comprises a selection of cards with black and white stimuli, together with toys of different size and colour, which are hung on a string and presented in front of the child. Their response, ranging from noticing the hanging toy, to following it as it is moved around in front of them, to reaching out and holding it, is observed and documented. It has been validated as a reliable, portable and speedy tool for assessing the visual function of children with severe learning disability in whom other tests fail to elicit any response. The BVFB offers an option for children for whom other formal tests are unsuccessful in eliciting a response.12 It is available from SeeAbility (go to www.seeability.org).

Figure 3: Some toys and flashing, coloured lights to help maintain attention

Figure 3: Some toys and flashing, coloured lights to help maintain attention

Figure 4: The Bradford Visual Function Box

Figure 4: The Bradford Visual Function Box

Understanding behaviours

Children and young people with learning disabilities may display certain behaviours, which can be difficult to understand. A range of behaviours are often seen, including:

- Aggression; such as hitting or hair pulling

- Self-injurious; such has head banging

- Destructive; such as throwing things or ripping items

- Sensory seeking behaviours; such as rocking or ‘flapping’ and perhaps most important to eye care professionals13,14

Often these ‘challenging behaviours,’ which can be stressful and upsetting, are much misunderstood, even by parents and carers, resulting in poor access to health services.13

Understanding both a child’s preferences and their sensory sensitivities (to noise, touch, smells or visual stimuli such as bright lights) are really important. Both a pre-assessment questionnaire and the presence of a parent or teacher during an assessment will determine how comfortable a child remains and thus the success of the assessment. Knowing a favourite song, nursery rhyme or activity can transform an assessment; with a child fully engaged and a clinician better able to make visual observations and tailor a visual and eye health assessment with the most suitable choice of clinical tests.

Visual processing disorders

Difficulties with visual processing affect how visual information is interpreted, or processed by the brain. Visual processing, or perceptual disorders, are often considered as brain sight disorders, even when ocular health and visual acuity levels are good. There are a number of ways that the brain struggles to process and understand the sensory input from the eyes;15 further information can be found in the Optician series on CVI, beginning 22.03.2019.

Adaptations to clinical techniques

The assessment of children with learning disabilities may be challenging, requiring greater patience, different skills, and a broader range of assessment instruments than their typically developing peers. A versatile and flexible approach is key to a successful assessment.

Overarching any clinical assessment is the importance of engaging and reassuring a child on initial entry. Parents, carers, and teaching assistants prove pivotal, as a child will feel safe and comfortable with an individual they trust.

Demonstrations and explanations transform an assessment offering a child reassurance and enabling them to understand what is coming next. Covering the teaching assistant’s or parent’s eye first, or even your own, can work well to demonstrate to the child what is coming next and expected of them.

Tailoring an assessment is also very effective; on initial entry of each child, their body language and behaviour will communicate the best approach and determine the best test to start with. Starting with more fun and less invasive tests can really relax and engage a child. Often an assessment starts with asking a child to catch a flashing ball of known diameter, and then moving to the toys of the Bradford Visual Function Box. Observation of their response offers so much information on their visual status within the first few seconds, and provides an opportunity for them to sit down and get settled; thereby enabling the start of a more formal clinical assessment. Mixing up an array of clinical tests according to the order a child may be most receptive to them is one of the most rewarding, and yet challenging, aspects of assessing children with learning disabilities.

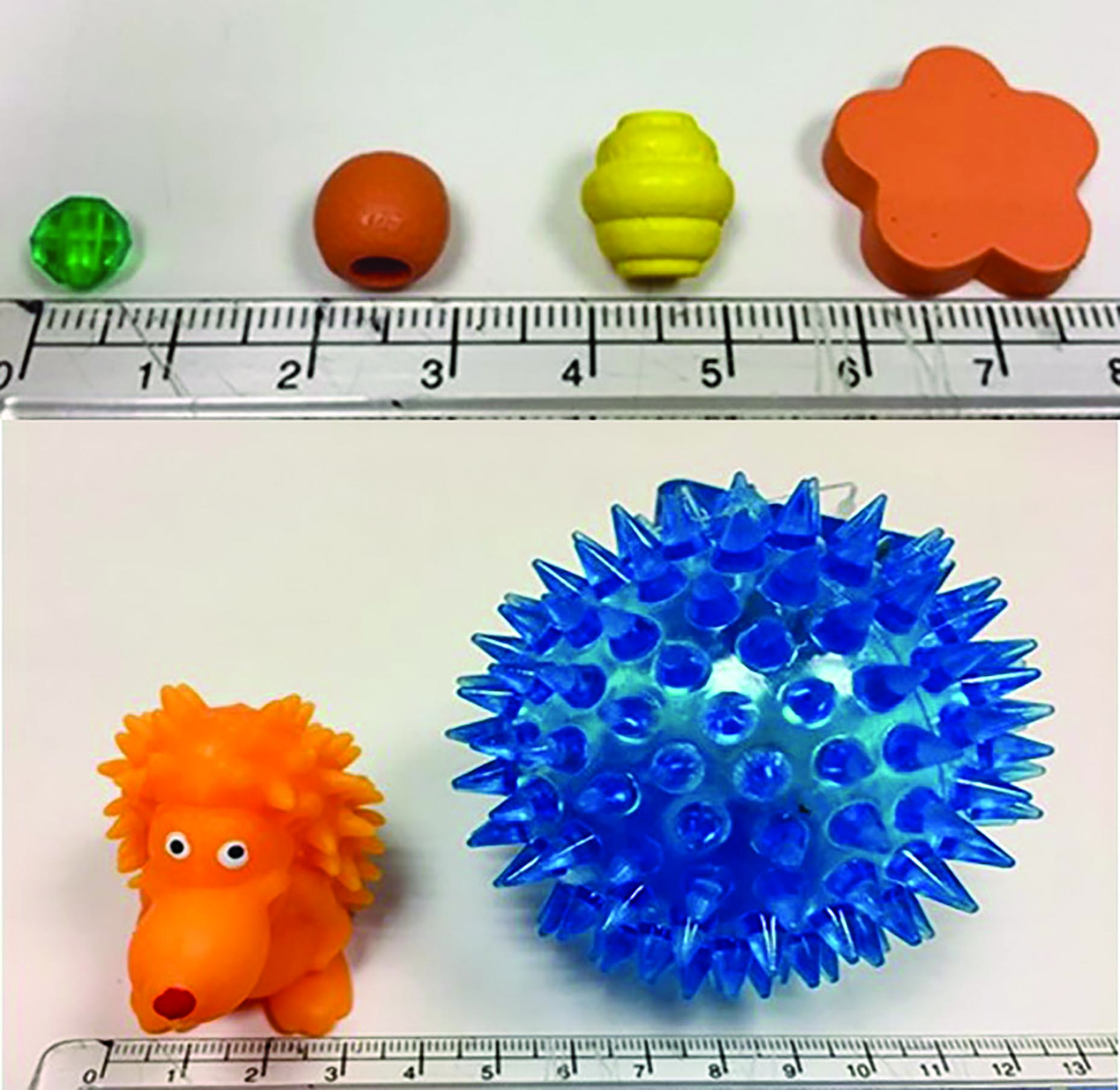

Coloured lights can be very engaging and effective to assess pupil reflexes and motility, perhaps with an animal pen before moving onto vision tests (figure 3). Offering them a pen torch or fixation stick to hold themselves may be a good way to help a child feel in control and reassured. They may also go on to check their own pupils and convergence. If the fixation stick proves interesting to them, it may be a good opportunity to conduct both cover-uncover and alternating cover tests within the first few minutes. Playing with fun-designed spectacles, thereby introducing the occlusion specs; where one eye is frosted or blacked out, to check monocular visions is also a good starter to engage a child before the more formal tests. Occlusion, or indeed bringing any instrument or toy close to a child’s face can be difficult to tolerate. Asking a carer familiar to the child to model the occlusion specs is a good strategy, then offering them to the child to put them on the carer, and then onto themselves. Stereoscopic tests can also be very captivating; often a Frisby test can be a winner as an initial test (figure 5).  Figure 5: The Frisby test

Figure 5: The Frisby test

It may be that some tests are not possible to complete, despite repeat attempts and strategies. If so, this should clearly be noted on the records along with reasons, for example ‘causes significant distress’.

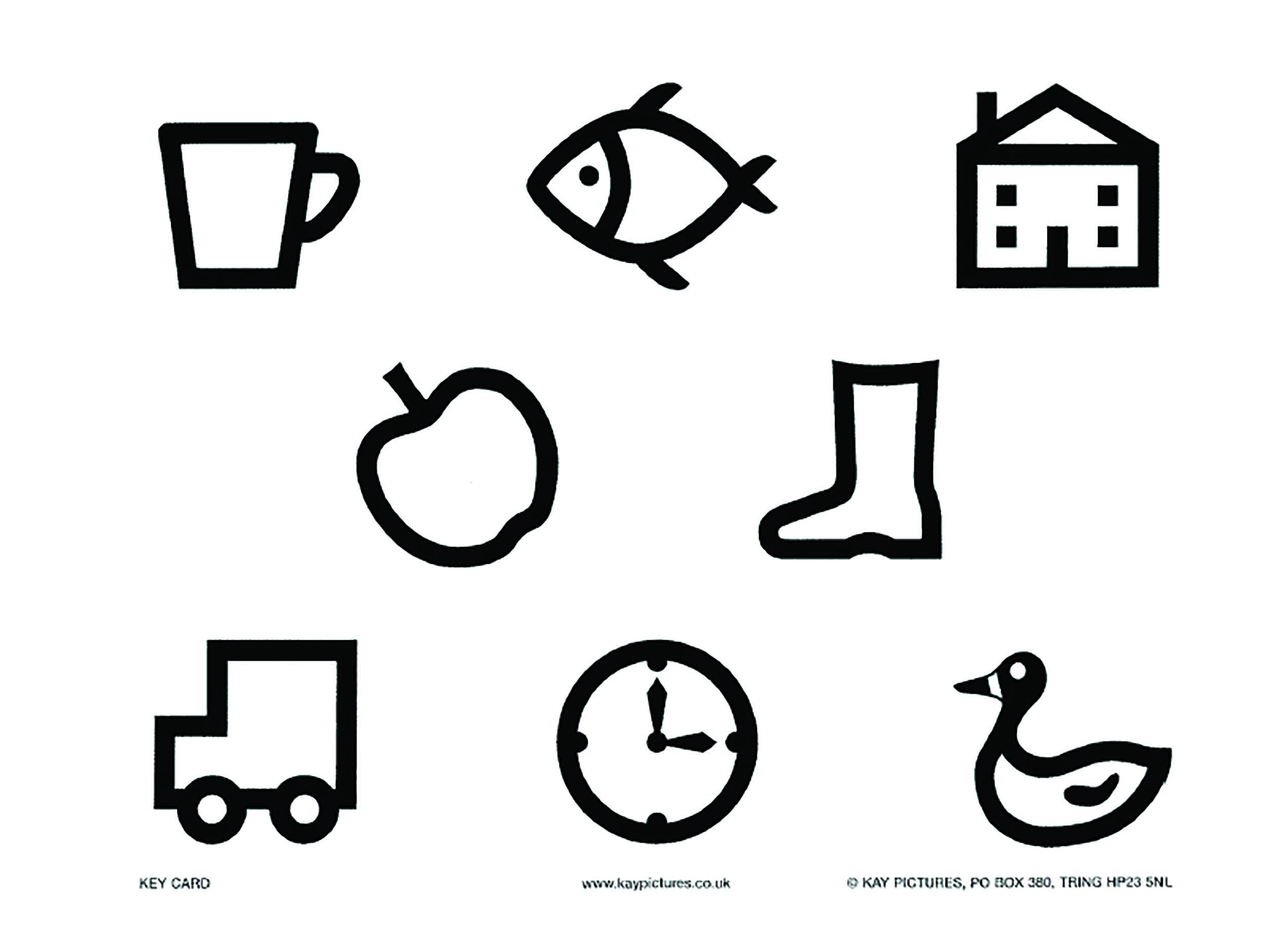

Preferential looking systems, such as Cardiff Cards (see figure 6) or Keeler Acuity Cards, can be useful if the patient is not able to recognise pictures or symbols. Signing Kay pictures may be easier than picture matching or naming, as indeed may single uncrowded optotypes rather than crowded singles (figure 7).  Figure 6: Cardiff cards used as a preferential looking test of vision

Figure 6: Cardiff cards used as a preferential looking test of vision

Figure 7: Kay picture card for matching

Figure 7: Kay picture card for matching

The new ‘say and match’ app from Kay Pictures Ltd offers an opportunity for carers and teachers to familiarise children with the Kay pictures prior to an eye examination.16 Using a combination of tests can often be really helpful to maintain engagement and support the clinician within a short timespan to understand effective communication strategies and behaviours. In some assessments, when the challenges of communication prove too great, observational clues have to be relied upon to assess the level of vision. Even with poor engagement, such as with a child that does not remain seated, the BVFB can be used with a mobile child to see if they perceive the hanging beads held out in front of them. Vitally, the BVFB allows some measure of vision to be achieved, even as a building block to future assessments. Further visits may be planned if a parent or carer feels a child’s behaviour during an assessment, in an unfamiliar setting and with a clinician they do not know, is atypical.

The importance of ascertaining near visual acuity cannot be emphasised enough with the high incidence of binocular vision and accommodative weakness anomalies in children with a learning disability.17 The Kay near vision test can be very useful for this, either directly after distance visions if a child remains engaged, or after a break with another test (figure 8).  Figure 8: Kay picture near test card

Figure 8: Kay picture near test card

The reliability of any findings together with difficulty conducting some tests should be clearly documented with notes about the level of engagement. As an example, a short attention span or poor co-operation may be the cause of a measurement of reduced visual acuity rather than actually poor vision or visual acuity.

Communication strategies

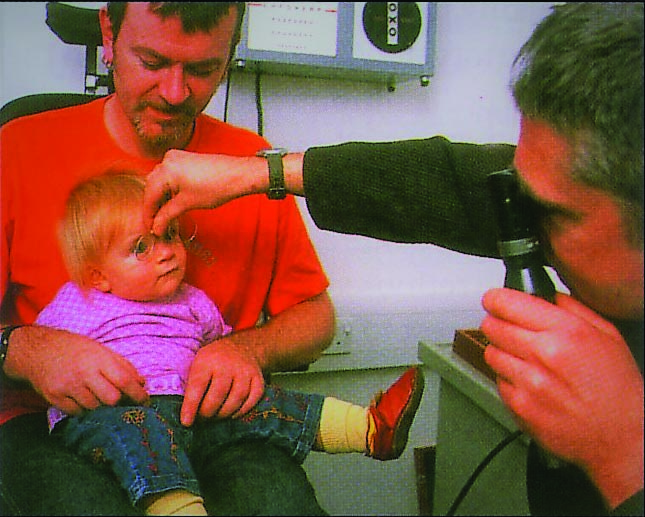

Effective communication is fundamental to a good visual and ocular assessment. Observing how a parent or carer communicates with a child can be very useful at the beginning of an assessment, followed by replicating their style (figure 9).

Figure 9: Effective communication is fundamental to a good visual and ocular assessment

Figure 9: Effective communication is fundamental to a good visual and ocular assessment

Speaking directly to the child is important with simple phrasing and questions. Closed or binary response questions can be helpful. Extended time to process and react to a request or instruction is key. The ‘Wait 8’ strategy, where a clinician routinely waits eight seconds for a response before repeating or trying a different approach, is a useful tool, allowing the child enough time to respond and for the clinician to make observations before moving to another test. Repetition, using keywords a child understands, and pointing and natural gesturing with a relaxed tone can all be very effective at ensuring a child feels safe and reassured. Parents and carers will also know of other communication channels preferred by a child. Examples include:

- Specific communication boards or books

- Photos and symbols

- Sign language; such as Makaton, which uses signs and additional symbols in conjunction with spoken language. The ‘Understanding your eye test, for Makaton users’ booklet can be found on the SeeAbility website.18

Assessing Visual Function

Visions/visual acuity

An assessment of presenting vision is fundamental to understanding visual function. Effective communication strategies will be known from the pre-assessment questionnaire and the input of a parent or teacher and will determine the initial choice of vision assessment test. Even when communication is very challenging, preferential looking tests such as LogMAR Keeler cards and Cardiff Cards may give some measure of vision. The Bradford Vision Function Box proves very effective, asking a child to reach for a 40mm ball, or smaller beads, ranging from 5-15mm, hanging on a string.

For children that are more interactive, the Kay Picture test can be used for children to sign, match or name the pictures they see.

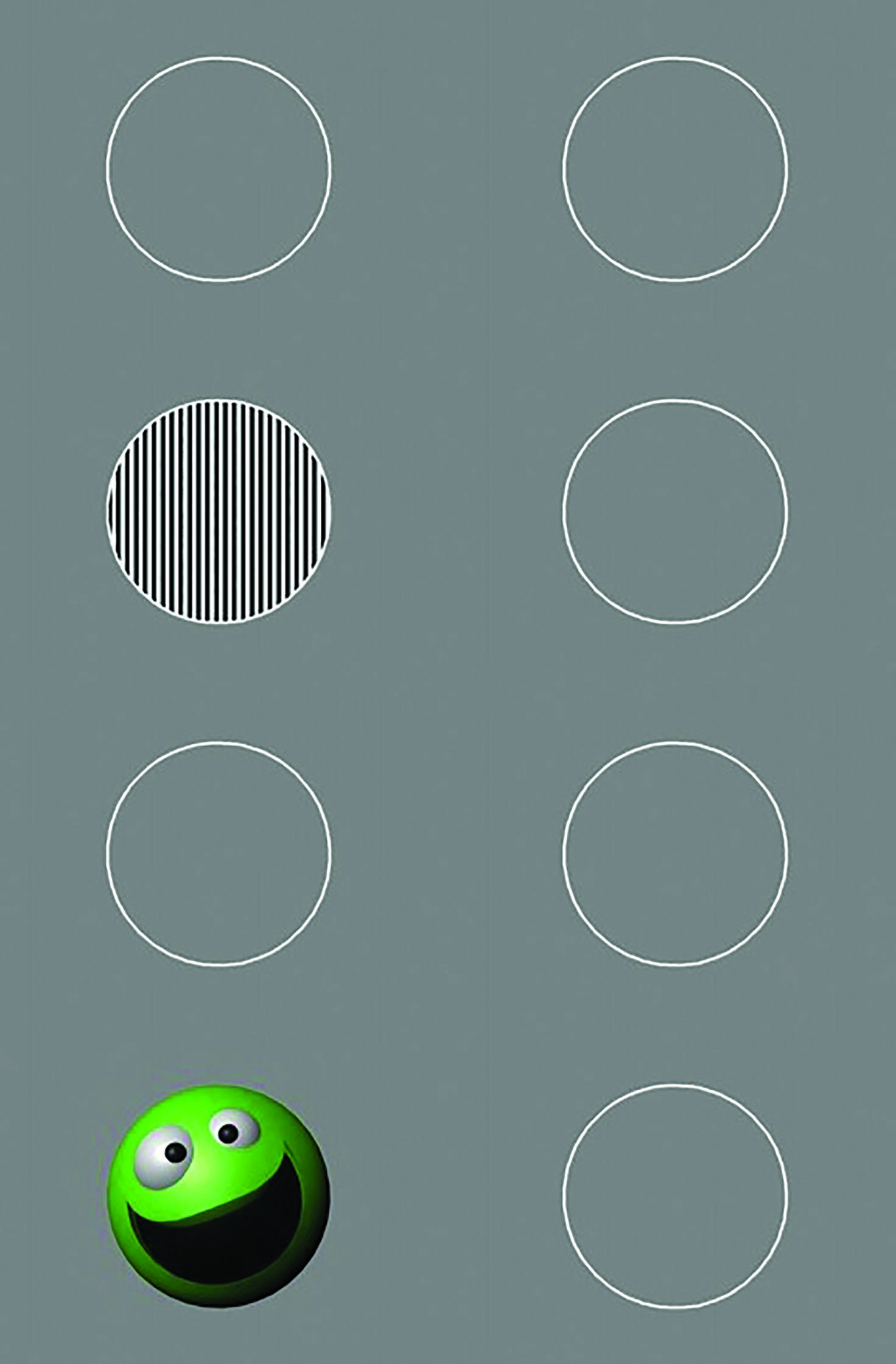

The Peekaboo test is an app based electronic visual assessment tool (figure 10) which has frequently, in the author’s experience, proved to be effective to engage a child’s attention when this has not been possible with other tests. Comprising a number of circles with black and white gratings, it relies on preferential looking to measure vision, but can be more reliable asking the child to indicate where they see the gratings of progressively thinner gratings, ‘rewarding’ them with an engaging congratulatory voice note every time they discern the circle with the grating.

Figure 10: The Peekaboo test

Figure 10: The Peekaboo test

Offering an option to choose which test they want to do can be effective to engage a child and offers a more thorough assessment of vision. The Bradford Visual Function Box is often a good starting point, asking a child to reach out for the beads, and then moving on to either a preferential looking or more interactive test according to their communication style and level of engagement.

Allowing a child enough time to respond to the vision tests, even the preferential looking tests, is really important. In addition, a qualitative note about the reliability of a vision or visual acuity is vital to document.

If no visual response is elicited from any of the tests, observational clues have to be relied upon to assess the level of vision. Gross changes in room light levels help to conclude if a child is able to perceive light if no response is seen with pen torches or other illuminated toys. Ocular reflexes should also be assessed when it has been hard to evidence useful functional vision-test for a blink reflex, optokinetic nystagmus (OKN gratings can be downloaded in visual assessment applications) and a vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) can be tested by observing if a forced head movement elicits compensatory eye movements indicating fixation is being maintained.

Occlusion can be difficult to tolerate. In assessments where a child objects to wearing the occlusion spectacles, asking a carer to help and cover each eye with their hands, rather than using the spectacles or an occluder can be helpful, and more comfortable to the child. Even when accurate monocular visions are not possible, it is important to discern whether the objection is equal for each eye, as an unequal response may indicate a difference in monocular acuities and is a cause for concern.

In children with no known previous ophthalmic assessment or history, where no visual response is evoked with any of the visual tests, or there is suspected CVI, consider referral to a specialist in secondary care and/or for support by a teacher for the visually impaired (QTVI).

Near vision

The importance of ascertaining near visual acuity cannot be emphasised enough with the high incidence of binocular vision and accommodative weakness anomalies in children with a learning disability.17 The Kay near vision test can be very useful for this, either directly after distance visions if a child remains engaged, or after a break with another test.

Contrast sensitivity

Assessment of contrast sensitivity with Cardiff Contrast Cards or Hiding Heidi cards (figure 11) is recommended to facilitate an understanding of visual abilities. Contrast sensitivity has been shown to be reduced in some children with learning disability.19-21

Figure 11: Hiding Heidi cards for the assessment of contrast sensitivity

Binocular status

Corneal reflexes offer a really simple method of ascertaining whether a large angle squint is present. A pen torch with an engaging toy can be a very speedy method of conducting the Hirschberg test together with motility and, for children unlikely to wear the occlusion specs, offer an opportunity to cover each eye to determine grossly if a child objects strongly to occlusion of either eye.

The 20Δ base out prism test proves to be a very effective, fast and easy test, and really helps determine the presence of motor fusion and gross binocular vision, especially if a child responds with strong objection to occlusion. To undertake the test, a pen torch or toy holding fixation is used in conjunction with a 20Δ base-out prism. In the presence of binocular vision, the eye covered by the prism moves in towards the apex of the prism. To ensure bifoveal fixation, the other eye also moves in (thereby ‘overcoming’ the prism). To ‘recover,’ the uncovered eye then moves out, and the covered eye moves out with it. Difficulty overcoming the prism should be interpreted cautiously. This may indicate reduced acuity in one eye, the presence of strabismus, a reduced fusion range (a 10Δ can also be used and may elicit a response if base out fusion ranges are reduced) or a lack of response to induced diplopia; with the child tolerating the double vision.

Ocular movements and nystagmus

Any nystagmus should be noted and its type and amplitude recorded. Ask family or carers if the amplitude increases at any time, typically this happens with tiredness or stress. Amplitude may be significantly greater on occlusion of one eye so that monocular acuities will be much reduced when compared to binocular which gives a truer indication of the impact on functional vision.

Convergence and motility testing are essential. Convergence may not impact upon the amplitude of nystagmus or may lead to an increase or decrease and so this should be assessed and will impact on near acuity.

During motility assessment, look for a null point, an eye position in which the amplitude of nystagmus is at its minimum. This should be noted and communicated to family and carers so that the child can be supported to use it to obtain optimal VA. Children may have a compensatory head posture (CHP) which allows them to use the null point and it is important that this is understood so that it is not discouraged. For example, a child with limited head control may be prevented from achieving optimal visual acuity because a physiotherapist well intentionally encourages a head position away from the null point with wheelchair head rests. Motility can be performed with a flashing or noisy toy to maintain interest. As always, look for any restrictions of movement and for the presence of smooth and accurate pursuit movements and accurate saccades.

Poor eye movement control is a common observation in children with learning disabilities and is known to be associated with CVI.20,22 Eye movements may also be delayed by just fractions of a second. This has significant potential impact in education and day to day functional vision. Inaccurate saccades will also produce challenges. Any eye movement anomalies need to be carefully communicated and their practical implications clearly explained to allow coping strategies to be developed.

Strabismus

Corneal reflexes will give some indication of the presence of strabismus, yet further assessment to determine direction, frequency and comitancy is important. The cover and uncover test in the primary position of gaze, followed by observations in all directions, taking note of any compensatory head posture evaluates whether a deviation is comitant or incomitant. Controlling accommodation with near targets during cover and alternate cover tests, in conjunction with dynamic retinoscopy will determine best management options for treatment and referral of a strabismus.

Refraction

The value of accurate retinoscopy cannot be overstated. Good retinoscopy skills provide a vital measure of visual function in children with learning disability (figure 12). Suggesting the child lowers the room light levels themselves can be an effective way to get started with retinoscopy, but any warning that light levels are going to change is important. If it is apparent a darkened room will distress a child, retinoscopy can be attempted with room lights on, even if to assess clarity of optical media and detect any strabismus or retinal anomalies. Comparison of the retinoscopy reflex between both eyes, even with room lights on will reveal any marked difference in refractive status. For some assessments, this may be all that can be achieved for the first assessment.

Figure 12: Steps to minimise anxiety during retinoscopy are helpful

Figure 12: Steps to minimise anxiety during retinoscopy are helpful

Initial sweeps of non-cycloplegic retinoscopy, unaided or with a child’s current spectacles, are recommended over and above the instillation of cyclopentolate, the use of a trial frame, and even trial lenses (figure 13).

Figure 13: Avoiding a trial frame

Figure 13: Avoiding a trial frame

Visual and musical stimuli, such as revolving flashing torches, tablet apps to trace shapes, numbers or letters such as ‘Fluidity’ and ‘Popping Bubbles’ and favourite nursery rhymes, can be very effective in engaging a child, often enabling hand-held lenses to be held up in front of both eyes. Distance and near fixation targets can give clues to how well the child is overcoming hyperopia or controlling their accommodation even with very limited cooperation. Simultaneous refraction of both eyes; effectively comparing the refraction of each eye, with fogging of the eye not being refracted is important to control accommodative instability. An unbalanced prescription resulting from either poor control of accommodation or poorly controlled fixation can induce anisometropic amblyopia.

Once the distance refraction has been measured for each eye, asking a child to fix on a near target enables an assessment of how accurately accommodation has been controlled, and whether it can be sustained on a near target. Dynamic retinoscopy provides a rapid assessment of accommodative ability. The key to the technique is the neutralisation of the retinoscopic reflex that occurs when the patient accommodates on this near vision target held in the same plane as the retinoscope. Once the distance correction is established, dynamic retinoscopy, with fixation on a near target can be performed even with the lights on. It is an especially important technique for children with learning disability with high prevalence of accommodative anomalies, as it reveals whether a child is over-accommodating, under-accommodating, or if there is an imbalance between the two eyes. In effect, dynamic retinoscopy facilitates the provision of near vision correction in children who would otherwise struggle in their educational development.

Cycloplegia

Undoubtedly the most accurate distance refraction, as well as the clearest, and widest view of the retina is facilitated with cycloplegia. However, non-cyclopelgic retinoscopy enables a clinician to understand a child’s accommodative function and tolerance. Additionally, initial experiences of eye examinations remain positive when a child feels reassured and able to develop rapport with an unfamiliar clinician without the trauma of drop instillation.

In cases where initial refraction and assessment reveals it is absolutely necessary to dilate, the cyclopentolate (1%) Minims can be given to parents, carers or even school nurses (with written instructions) to instil for a second assessment once visions, binocular vision, stereopsis and refraction have all been attempted.

Ocular health

Cooperation is key for a good assessment of a child’s ocular health. With the help of a parent or carer, both demonstration of ophthalmoscopy and distraction with engaging toys or a favourite video or song are really helpful. While direct ophthalmoscopy can work well with compliant children and an effective distraction strategy, often assessment of the health of the fundi needs to be very quick. Especially when undilated, the wider field of view of the PanOptic ophthalmoscope, or a direct ophthalmoscope with a 20D lens are effective strategies and facilitate a larger field of view and greater working distance, which is more comfortable and less invasive to the child.

Reassurance is key, so a child feels safe. Often, second attempts are necessary. Fundamentally, the clinician should aim to determine clarity of disc margins and health of the macula, even if more in-depth assessment is not possible. Documenting what enabled a good ocular health assessment is really helpful for future assessments, and conversely, notes about a poor view of the fundi should be as thorough as possible with a plan for a second attempt as soon as possible.

Visual fields

Even a gross assessment of visual fields is imperative in every child with a learning disability as gross field defects are common, especially in children with cerebral palsy.22 It can be conducted as a game with a favourite toy with a carer sitting in front of the child and can easily be made into a fun activity. It may be necessary to use observations of eye movement towards the target as a sign it has entered the visual field, or the child can be asked to ‘catch’ the toy (figure 14). It is important to ensure any visual field defect is shared and carefully explained to parents, carers and the multidisciplinary team. Even with previous known ophthalmic history, often such clinical findings are not effectively disseminated to other health professionals, such as occupational therapists and physiotherapists who develop mobility and rehabilitation plans.  Figure 14: Functional field assessment with both eyes open

Figure 14: Functional field assessment with both eyes open

Dispensing

The role of the dispensing optician is pivotal in ensuring optimal visual performance. Children with learning difficulties frequently need refractive correction. Prescriptions tend to be higher and accommodative problems are common, so that more than one prescription is needed.

A child’s occupational requirements need to be carefully considered. If a child uses assistive communication technology such as a screen mounted on their wheelchair or an iPad, this needs to be considered when dispensing. Eye movement control and head control as well as any nystagmus null point or visual field defect all need to be considered when dispensing to provide optimal visual function. For example, a child who uses a screen at ½ metre mounted on their wheelchair may need a prescription specific to that distance. For some children, multifocals may be the best solution.

However, if eye movement control is limited, or the visual fields requirements of an assistive technology device are large, separate pairs may be indicated. If a child is using EyeGaze software,23 which is operated by tracking software allowing eye movements to be used to communicate, they will need a good anti-reflective coating. The optometrist or dispensing optician is well placed to suggest such means of communication, as a child considered to be cognitively unable to access such technology, may in fact be limited visually, especially with a recently discovered and significant refractive error. Frame fitting will be influenced by facial characteristics, sensory sensitivities, the use of hearing aids and wheelchair headrests.

Adaptation to Refractive Correction

It should be expected that significant support will be needed for children to successfully adapt to new or significantly changed refractive correction. This should be effectively communicated to family, carers and the wider health and care multidisciplinary team involved with the child. It is frequently, unfortunately, reported that a child did not like their spectacles so they probably were not helping (or maybe were not right as the child could not give subjective responses). Explaining how the prescription is

calculated from physical measurements of the eye, and demonstrating the blur experienced without the correction (to family and carers) can get them on board to support adaption.

It should be noted that, even in the presence of significant CVI, refractive correction is evidenced to be beneficial and so should be supported.24 In SeeAbility services, we see spectacle dispensing as a proactive therapy, like patching. You would never prescribe patching and not plan to follow up. Our dispensing opticians have a caseload of children who they follow up routinely until they have achieved successful spectacle wear.

Having a spare pair of spectacles can help avoid significant setbacks and the NHS England special schools eye care model acknowledges this need. All children prescribed spectacles for the first time or given a significantly changed prescription will be booked in for a follow up, and we strongly recommend a similar approach in all primary care. A follow up appointment at four to eight weeks after fitting allows any issues with fit or adaption to be addressed and, if necessary, strategies to support successful adaption to spectacle wear to be developed. Such strategies may include developing positive associations with the spectacles by putting them on at a favourite time of day or when about to embark on a favourite activity such as going for a walk.

For autistic children, building spectacles into a routine can be key; ‘I clean my teeth, I put on my spectacles.’ Even if initially the spectacles are only tolerated for a matter of seconds, gradually increasing this every day will usually eventually lead to adaption, and then the child will not tolerate lack of correction. Wearing the spectacles while active and distracted is encouraged as use while the vestibular system is engaged may speed adaptive processes.

Reasons for initial rejection of spectacles are multifactorial. Prescriptions are often high and may be given at a later age, as sadly children with learning disabilities are often missing out on timely care despite their high risk.25,26 Children, especially those with autism, may have both tactile sensitivity issues, so that it can be difficult to tolerate something on their face, as well as sensory processing issues so that it can be overwhelming adapting to a hugely different perception of the world.27 For many children with a learning disability, their processing will be slower and adaptions to the changed perception will be more challenging and take longer.28,29

Of course, ensuring optimal comfort is vital to successful adaption and so fit should be carefully, and continually assessed.

It is also worth giving specific advice to families and carers that spectacles use should be maintained when active. Too often, spectacles may be put away for outside play or when swimming, activities when the child may need a correction most to cope.

Therefore, parents need to fully understand the benefits of spectacle correction to their child’s vision. Demonstrating the blur their child experiences in a trial frame can help. Adapting to using hearing aids as well as spectacles is another sensory challenge not uncommon for children with learning disabilities.

Post Assessment Communication

We have covered some of the advice needed to be communicated for each child above when considering findings of different elements of the assessment but it cannot be stressed enough how vital good communication of clinical findings is to a child achieving optimal visual performance. We recommend a plain English written report be issued at the end of the examination for every child with a learning disability. SeeAbility’s ‘Results of my child’s eye test’ sets out a template for this (figure 15).30

Figure 15: Results of my Eye Test

Figure 15: Results of my Eye Test

If spectacles are needed, when they should be used and the expected visual effect should be explained. Ulster University has an excellent resource with downloadable examples of font size to illustrate vision/visual acuity levels, which can be included with the report. Advice on position in the classroom, position of visual tasks, such as toys, books and food, should be given for children with a field defect, nystagmus with a null point or eye movement control problems.

The report should be shared with family, carers and school and in the case of significant findings, these should be flagged for inclusion in a child’s Education Health and Care Plan in England, Individual Development Plan in Wales, Co-ordinated Support Plan in Scotland or Statement of Educational Special Needs in Northern Ireland.

Where you feel a child may benefit, ensure information is shared with other members of the team around the child. For example, you may wish to share information with speech and language therapists if vision and eye movement control indicates a child may be a good candidate for EyeGaze communication devices or if the child needs to use their spectacles to use their assistive technology. Physiotherapists need to understand a child’s field defect or null point of nystagmus when positioning wheelchair head rest supports. Teachers for the visually impaired need to know about any significant visual impairment as does a child’s paediatrician and of course their GP.

Consider referral to orthoptic colleagues for management of strabismus and to ophthalmology to confirm suspected diagnoses, for certification as sight impaired or severely sight impaired (this may be a requirement of involvement of teachers for the visually impaired) or for further investigations into possible CVI.

Summary

The examination of children with learning disabilities in primary eye care is an incredibly rewarding, and challenging, area of practice for both optometrists and dispensing opticians. It is no exaggeration to say it can be life changing. You may discover a -10.00DS myope at the age of 12, give a child a first prescription to correct poor accommodation so that they can see at near clearly for the first time, or help a parent finally to understand the impact of a hemianopia (it is so much more disabling than the effect when you close one eye).

Communication is key; successfully being able to communicate with the child and supporters to succeed with assessment and then communicating your findings effectively to support the child achieve their visual potential.

Sonal Rughani is a specialist public health optometrist and works with SeeAbility as well as acting as a specialist optometrist for the RNIB in London.

Lisa Donaldson is clinical lead for SeeAbility’s Special Schools Service, and primary care clinical lead for NHS England’s Special Schools Eye Care Programme, Visiting Lecturer at City, University of London and University of Hertfordshire.

References

- Donaldson L, Subramanian A, Conway ML. Eye care in young children: a parent survey exploring access and barriers. Clin Exp Optom. 2018.

- Das M, Spowart K, Crossley S, Dutton GN. Evidence that children with special needs all require visual assessment. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(11):888–92.

- SeeAbility, RCOphth, BIOS, LOCSU, CollegeOptoms A. Framework for Special Schools Eye Care [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Framework-for-Proposed-Special-Schools-Service-Final-ABDO-BIOS-College-of-Optometrists-LOCSU-RcOphth-and-SeeAbility-2.pdf

- Glover-Thomas N. The Health and Social Care Act 2012. Med Law Int. 2013.

- HM Government. Equality Act 2010. The Stationery Office Crown Copyright. 2010.

- SeeAbility. SeeAbility Factsheets and forms [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/eye-care-factsheets

- SeeAbility. About Your Child and Their Eyes [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jun 25]. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=6dfa9544-1e17-4681-a234-8751da345600

- SeeAbility. Results of your Child’s Eye Test [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=ce0d677d-c1a8-46fe-840b-429f75c43b89

- Dutton GN. Structured history taking to characterize visual dysfunction and plan optimal habilitation for children with cerebral visual impairment. Vol. 53, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2011. p. 390–390.

- SeeAbility. Functional Visual Assessment. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/fva?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIkLPlnO6S6QIViKztCh3pEAFJEAAYASAAEgLulvD_BwE

- Milling A, Newsham D, Tidbury L, O’Connor AR, Kay H. The redevelopment of the Kay picture test of visual acuity. Br Ir Orthopt J. 2015.

- Pilling RF, Outhwaite L, Bruce A. Assessing visual function in children with complex disabilities: The Bradford visual function box. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(8):1118–21.

- Morris J. Challenging Behaviour: A Unified Approach. Adv Ment Heal Learn Disabil. 2008.

- Rao JM. Brain development: Neurobehavioral perspectives in developmental disabilities. Clin Bull Dev Disabil Div. 2013.

- Koller HP. Visual processing and learning disorders. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2012.

- Pictures K. Kays Pictures Say and Match app. Available from: https://kaypictures.co.uk/product/kay-say-and-match-app.

- Woodhouse JM, Cregg M, Gunter HL, Sanders DP, Saunders KJ, Pakeman VH, et al. The effect of age, size of target, and cognitive factors on accommodative responses of children with down syndrome. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;

- SeeAbility. Makaton Having an Eye test booklet [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=7ad29304-bfc2-4f79-ba36-b354685a24e8

- SC, JMW. Detecting early keratoconus in Down’s syndrome. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;

- Fazzi E, Signorini SG, Bova SM, La Piana R, Ondei P, Bertone C, et al. Spectrum of visual disorders in children with cerebral visual impairment. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(3):294–301.

- Little JA. Vision in children with autism spectrum disorder: a critical review. Clin Exp Optom [Internet]. 2018; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29323426%0Ahttp://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1111/cxo.12651/asset/cxo12651.pdf?v=1&t=jcm5a7se&s=6615c4262383e358a03eb8eab6e280d3bca3ba32

- Elmenshawy AA, Ismael A, Elbehairy H, Kalifa NM, Fathy MA, Ahmed AM. VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN CHILDREN WITH CEREBRAL PALSY. Int J Acad Res [Internet]. 2010;2(5):67–71. Available from: http://login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=54352948&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Inclusive Technology. EyeGaze [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.inclusive.co.uk/hardware/eye-gaze-technology

- Williams C, Northstone K, Borwick C, Gainsborough M, Roe J, Howard S, et al. How to help children with neurodevelopmental and visual problems: A scoping review. Vol. 98, British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2014. p. 6–12.

- Pilling RF, Outhwaite L. Are all children with visual impairment known to the eye clinic? Br J Ophthalmol [Internet]. 2017 Apr;101(4):472–4. Available from: http://bjo.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-308534

- Woodhouse JM, Davies N, McAvinchey A, Ryan B. Ocular and visual status among children in special schools in Wales: The burden of unrecognised visual impairment. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(6):500–4.

- Kielinen M, Rantala H, Timonen E, Linna SL, Moilanen I. Associated medical disorders and disabilities in children with autistic disorder: a population-based study. Autism [Internet]. 2004;8(1):49. Available from: http://aut.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/8/1/49

- Behrmann M, Thomas C, Humphreys K. Seeing it differently: visual processing in autism. Vol. 10, Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2006. p. 258–64.

- Banai K, Nicol T, Zecker SG, Kraus N. Brainstem timing: Implications for cortical processing and literacy. J Neurosci. 2005;

- Results of your child’s eye test [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.seeability.org/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=ce0d677d-c1a8-46fe-840b-429f75c43b89