“Then Goldilocks went upstairs, and there she saw three beds all in a row. Goldilocks lay down on Father Bear’s bed first, but that was too long for her; then she lay down on Mother Bear’s bed, and that was too wide for her; last of all she lay down on Baby Bear’s bed, and there she fell asleep, for she was tired.”

(Robert Southey, 1837)

In her search for comfort, Goldilocks only establishes what is right by comparison. By identifying the difference between comfort and discomfort, we can help patients draw the boundary between too little and too much, without exhaustion for the patient or having to become angry bears.

Addressing a conference of eye-care practitioners (ECPs) in 2019, Professor Michel Guillon remarked that ‘contact lens discomfort (CLD) is the major problem associated with contact lens wear and the leading cause of discontinuation.’ He noted the need to precisely characterise the problem and how personalised management would have high impact upon clinical outcomes.1

Current Thinking

Research into the subjective experience of comfort,2 and ways to identify CLD,3 demonstrates an active interest in getting the approach just right. Helping patients achieve the best vision care and sharing knowledge about the right options is central to our profession. ECPs want to support their patients in choosing contact lenses and feeling comfortable when wearing them.

Industry research into patient awareness and compliance with advice set out by the British Contact Lens Association4 tells us that more than half of contact lens wearers are aware of 80% of such advice and about a third are aware of over 50% of guidance. We know then that patients may be ready to listen to and act upon the CLD advice they are given. We can appreciate the potential readiness for patients to listen to what is just right for them. But are we willing to tell them?

However, awareness varies significantly between different key groups of contact lens wearers; and in terms of aftercare, just 48% recall receiving aftercare advice at their most recent contact lens check-up. For those patients who have been wearing contact lenses for over 20 years or those buying online, these are the least likely to receive any advice at all. Some patients, therefore, feel they never get the chance to make choices with their ECP about what is just right for them.

The optical profession itself sees significant risk in poor communication with patients and not being candid when things go wrong.5 It has been suggested that poor communication could become more problematic in the future, and undergraduate education and CET need to evolve to better manage future risk and better prepare those newly qualified for practice. What is said, how and to whom seems to be of real significance.

We know that communication is widely taught in clinical education and that the way in which a patient is given information is as important as what is said to them.6,7 In optometric practice, communication is used to isolate and solve a problem, as a diagnostic tool, as part of the examination, and to establish rapport with the patient.8 Getting the balance right places a clear responsibility on the clinician to manage the information they provide and be mindful of how their patient will interpret it.9

Research has demonstrated a strong relationship between patient-centred patterns of communication and trust. Better communication also correlates with higher rates of compliance, particularly among children.10

By focusing on both the what and the how, we enable a patient to more readily understand what is going on and to take appropriate action to help improve their conditions or mitigate symptoms.

Good communication helps a patient to work out what is just right. When addressing CLD however, what happens when we cannot be sure of exactly what is too much or too little? How precisely do we identify ‘what’s what’? What happens when the ‘how’ is so subjective, complex and ambiguous?

Is there a role for a ‘Goldilocks’ scale to help a patient tell us what is too much, too little or just right? Can increasing our use of open and Socratic questioning help us determine what really bothers patients? How do you respond to Professor Guillon’s challenge to precisely characterise a problem that you know is there but cannot accurately describe or explain?

The TFOS international workshop on contact lens discomfort

The findings of the TFOS international workshop on CLD suggests a vital role for the clinician in making the unseen nature of this condition seen. It suggests a way of bringing features of CLD together as a system. Seeing CLD as a system allows specific issues to be recognised and interdependencies to be identified and managed.11

CLD is a frequently experienced problem, with most estimates suggesting that up to half of contact lens wearers experience this problem with some frequency or magnitude. This condition impacts millions of contact lens wearers worldwide 12 and is also the leading cause of dropout from contact lens wear.1

The TFOS international workshop notes a lack of consensus and standardisation in the scientific and clinical communities on the characterisation of the condition, the influence of contact lens materials, and the proper design of clinical trials. Broadly, the literature identifies there is too little attention paid to CLD. There is too much evidence to deny its importance but getting the approach just right for ECPs has hitherto been underrepresented. Notwithstanding this, it is emphasised how clinicians must be diligent in working with patients with CLD.

It is important that the process of prevention and management starts early, perhaps even before the onset of symptoms, to improve the long-term prognosis of successful, safe, and comfortable contact lens wear.

In starting early, however, it may be difficult to help patients experience the impact of something they have not yet experienced. Managing patients in such circumstances requires careful, individual assessment to eliminate concurrent conditions that may confuse the clinical picture, followed by a determination of the most likely cause or causes and identification of corresponding treatment strategies.

There is an approach to this type of patient enquiry, akin to defining traces: the signature left by an absent thing that tells us of its presence. When enough things are absent, that absence can take on a presence of its own.13 On this basis, CLD could be approached by an assessment that looks for the undecidable, that is, something that cannot conform to either side of an opposition. The logic for this would be: ‘If I cannot confirm comfort, then a trace of discomfort may exist; if I can confirm comfort, then I have ruled out traces of discomfort.’

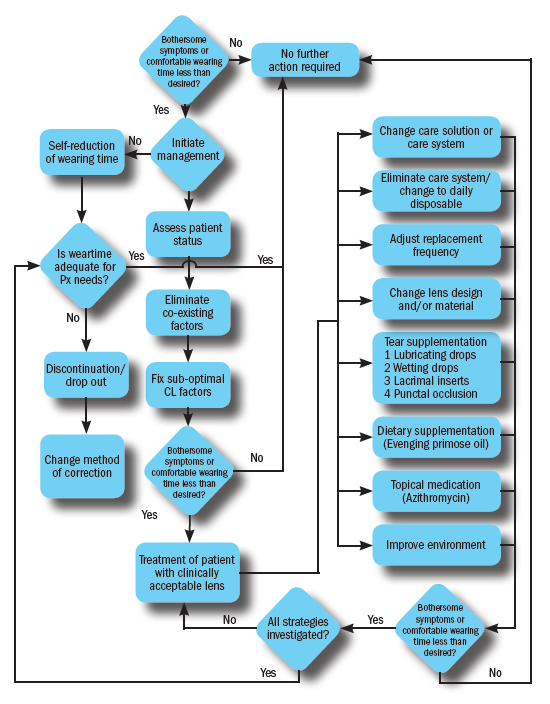

Reports of the TFOS committees set out a clinical framework for use when faced with an individual complaining of CLD (figure 1).14 This framework begins with history taking, moves on to identify any confounding conditions, before turning to the examination of the contact lens itself.

Figure 1: TFOS management strategies for CLD14

Figure 1: TFOS management strategies for CLD14

The purpose of the framework is to arrive at the point where everything has been done to optimise the contact lens environment, with the needs and individual characteristics of the wearer taken into account. Only once this has been achieved can the true extent of the underlying CLD be appreciated and remedied. This paper argues that scientific and industry stakeholders should investigate ways in which trace identification can be adopted as evidence led practice.

Adapting routines

The framework for consultation for CLD proposed by TFOS invites ECPs to build an evidence-led approach through effective patient communication. We know that improved communication can benefit all areas of practice, from improving clinical outcomes to making more efficient use of time, cost and quality.6 Health psychology research into communication in eye care recognises the importance of a patient-centred approach, involving the patient and ECP working in partnership to agree the best outcome and how to achieve it.8

Here, the practitioner contributes their clinical knowledge and experience while the patient is an expert on their own requirements, expectations and lifestyle. By contrast, in a more traditional, paternalistic approach, the practitioner identifies the ‘best’ outcome from their own perspective and gives the patient instructions about what needs to be done to achieve that outcome.

Industry research into optometric models of health consultation typically divide the optometric consultation into three distinct stages – history and symptoms, examination and ‘disposal’. This is arguably is an unnecessary, ‘doctor-centred’ approach.15

The dynamics of the interaction between ECP and patient have been described as a process of ‘unfolding’. The dialogue of the consultation itself creates meaning, priming both ECP and patient for what comes next. One statement anticipates another, signposts the next stage or prompts a probing question.

It is possible that patients may sometimes avoid saying ‘yes’ to having problems, even when they have symptoms to report, highlighting that there is much to be gained in a CLD conversation by building rapport to deliver optimal outcomes.

Other key issues in contact lenses practice, such as poor compliance, are heavily influenced by inadequate or infrequent communication. Helping patients understand the advantages and consequences of compliance behaviours, for example by supporting verbal advice with written guidance, is known to achieve greater consensus.16

In short, applying the principles of social interaction aids improved compliance for contact lens wearers.17 Adopting more rapport-based, conversational approaches seems more appropriate for CLD management as it requires the mutual investigation of an adaptive problem.18

Adaptive problems

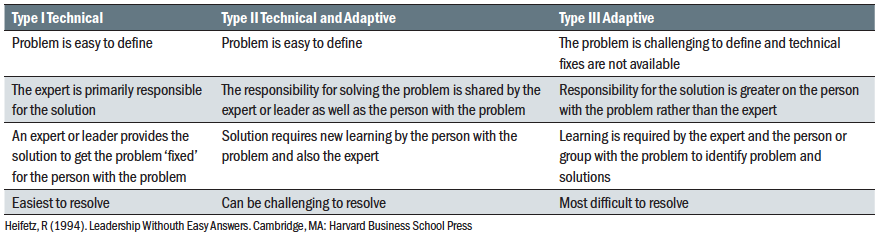

The multifactorial issues present in trace identification when resolving CLD are arguably an example of an adaptive problem. Adaptive problems are distinctly different from technical problems.19 The differences between the adaptive and technical problems are outlined in table 1.

Table 1: Adaptive and technical problems

Table 1: Adaptive and technical problems

Of course, the subjective experience of any patient will make the management of their condition more adaptive than technical. But, imagine approaching CLD as an adaptive problem in the first place, and communicating it as such to the patient. By doing so, you are involving the patient in the detective work from the outset, asking them to look for signs, symptoms and traces of something that is not right (because something is too much or too little, perhaps).

Working with, rather than avoiding complexity presents different ways of approaching the consultation process. It requires an alliance, where joint stakeholders think together about the problem, learn from each other about what can be done, and share the lead on ways to mitigate risks or improve symptoms.20

In this way, an ECP and patient are addressing the problem of CLD as a technical and adaptive problem. Both parties collaborate together in thinking about CLD as part of the TFOS system for optimal CL comfort. Together, ECP and patient establish how different elements interact with one another and achieve insight about the whole system. By assessing individual parts or fragments only, by staying technical, the working alliance of ECP and patient may miss the traces of something that is present through its absence.21

Taking this approach may be harder to integrate into existing models of clinical decision-making, drawing the Type 1 and 2 curricula of medical education together into one system; knowledge acquisition and problem solving. Further, it asks the ECP and patient to both ‘play doctor’ by focusing on problem-solving and clinical reasoning skills22 to address something that is part technical and part adaptive. Perhaps there is an argument for the whole practice team to embrace practice based continuing education and training in clinical problem-solving skills.

Effective consultations and the bothersome protocol

The ‘three function’ approach to clinical consultation is a strong example of best practice.23 It stresses the importance of the following:

- Building the relationship with patient

- Assessing to achieve understanding

- Collaboration for effective management

Building the relationship with patient

Instead of thinking about how to ‘fit’ the patient into any proposed TFOS CLD best practice ‘routine’, it may be more useful to think about how initiating effective communication and

establishing rapport creates the best climate in which a patient can join in with the adaptive problem solving process and learn how to ‘look for traces’.

Some common principles of effective patient interaction established by industry research6 suggests that a complementary approach to clinical formulation may already exist as best practice in joint clinical problem solving as follows:

Clarifying concerns

- Establish a reason for the visit and the major concern

- Ask open questions and use active listening techniques

- Elicit opinions and feelings as well as facts

- Pitch language at an appropriate level for the individual

- Avoid negative words such as ‘problem’

- Look out for non-verbal cues such as posture and gaze

Facilitating investigation

- Empathise with the patient’s concerns

- Signpost your strategy for addressing concerns

- Seek permission to proceed – essential for physical contact

- Explain each procedure as you go along

- Acknowledge and summarise during the conversation

- Allow the patient to confirm or correct any misinterpretation

Agreeing a plan

- Ensure all concerns have been addressed

- Explain the various options available and agree a plan

- Set realistic expectations for outcomes

- Give simple take-home messages

- Support your advice with written or online information as needed

Building a rapport

- Adopt an appropriate level of formality

- Use positive body language and facial expressions

- Maintain eye contact, and pay attention to gaze and body movements

- Remove physical (eg deafness, noise, interruptions) and emotional (eg fear, nervousness, prejudices) barriers

- Make the patient feel at ease

- Identify with the patient

Being in rapport with your patient provides higher quality information. This helps the ECP make better decisions and give higher quality recommendations. You have achieved rapport when your patient tells you what they think, why this is so and how they feel. When people feel significant, competent and likeable and the more we feel these needs are being met, the more likely it is we will fully engage with others and say what we think and how we feel.24

Getting the balance right places a clear responsibility on the ECP to manage the information they provide and be mindful of how their patient will interpret it. The way in which a clinician decides to communicate can also be adversely affected by the way they perceive their patient; at times it is possible that an ECP will be more inclined towards rapport building where a patient is seen as compliant with the information and instructions they are being given.25

As part of rapport building, the way we interpret someone’s body language influences our response to it.26 We may feel drawn towards someone or feel more or less comfortable in their presence. We anticipate our response and work out what to say or do next.27-29

The more able we become at interpreting non-verbal communication, the more capable we become at understanding social interaction. Body language may indicate distinct personality traits that can create more emotionally intelligent interactions as the ECP works out what to do or say next and how to establish a joint problem-solving approach with the patient.30

Assessing to achieve understanding

The TFOS framework illustrates a protocol that seeks to identify ‘bothersome symptoms’ and/or whether comfortable wearing time is less than desired for the patient. The steps to be followed include assessment of the experience of a patient for whom symptoms may not be recognised as problematic or significant.

Here it is helpful to consider the ways in which a ‘Goldilocks’ or too little/too much (TLTM) scale may help a patient determine what is or is not ‘bothersome’.31-34 Again, we may be better off adopting an approach that looks for traces of CLD using the logic of confirming the absence or presence of something, and searching for its opposite.

As contact lens wear is usually seen as a ‘good thing’, then the idea of there being ‘too much of a good thing’ might be difficult to elicit from a patient by simply asking them to describe their experience of wearing something they believe to be fundamentally helpful to them.

A revised approach is to use the approach that Goldilocks and the Three Bears teaches us. To consider the ways in which something is too much or too little; to establish what is just right; to look at how any positive impact of being just right in one area can have an adverse impact on something else.

Imagine asking questions with TLTM ratings, such as:

- ‘Are there times when wearing your contact lenses for eight hours a day seems much too little (-4), the right amount (0) or much too much (+4)?’

- ‘When comparing the comfort you get from wearing your glasses and wearing your contact lenses, is the balance much too little (-4), the right amount (0) or much too much (+4)?’

Using TLTM ratings may demonstrate a curvilinear, inverted U-shaped relationship with lens performance. Such a shape may be the outline of CLD, showing the absence of comfort (or the presence of discomfort) that a patient can best describe by taking the Goldilocks approach to what is or is not bothersome.

Without having to specifically describe or explain CLD, the TLTM approach may support a patient to find a way to illustrate CLD. A range of TLTM questions as part of the TFOS framework may be worthwhile considering in relation to further investigation of how to assess for the presence and impact of CLD in either symptomatic or asymptomatic patients.

Collaboration for effective management

The TFOS committees emphasise the importance of determining the most likely causes of CLD and identifying corresponding treatment strategies. We have already discussed the complexity of the adaptive problem presented to the clinician and patient. Further, the scope, scale, risk and likelihood of CLD may be different for individual patients.

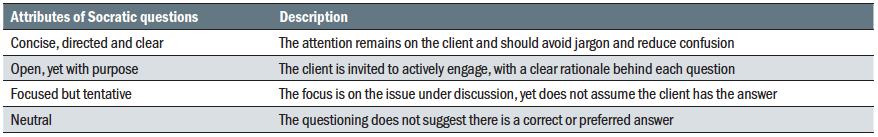

Rather than relying solely upon a Type 1 knowledge approach, it may be better to collaborate with a patient using the Socratic method.35 This technique is recognised as helping patients define problems, identify the impact of their beliefs and thoughts, and examine the meaning of events36 by using questions to ‘clarify meaning, elicit emotion and consequences, as well as to gradually create insight or explore alternative action.’37 Table 2 outlines the Socratic method.

Table 2: Key aspects of the Socratic method 38

Table 2: Key aspects of the Socratic method 38

With adaptive problems, it is good practice to gain as much knowledge as possible about the nature of the problem and predict the best possible outcomes together, recognising that adaptive problems will remain dynamic. By using Socratic methods, we are more likely to generate ideas and possibilities to resolve the adaptive problem. The following example considers Socratic dialogue in terms of gaining maximum information about a patient’s subjective experience of CLD:

- Thinking about the comfort of your contact lenses in general, how would you describe how they feel?

- Are they comfortable upon application?

- Are they comfortable during the day?

- Do they remain comfortable at the end of the day?

- Would you like to be able to wear your contact lenses comfortably for longer? Are there times that you find you have to take them out sooner that you would ideally like?

- Have you found your comfortable wearing time of your contact lenses has changed, or have you altered your wearing pattern (duration or frequency)?

Building a collaboration towards optimal eye health and the reduction of CLD therefore becomes a necessary goal of patient and ECP interaction. This can be assisted by Socratic dialogue, where the patient is an expert by their unique experience, and the clinician is the skilled helper. Change can be accomplished in this way, with patients more motivated to achieve sustainable change in the way they think and act.39,40

The relation between ECP and patient may have important effects upon the success of contact lens wear. Significant associations have been found between a clinician’s interpersonal skills and patient motivation and satisfaction.41

CLD training

What might be the impact of specific training in CLD communication for ECPs? In what ways might it address some of the key factors set out in the TFOS report? Perhaps we can start by looking at the benefit of enhancing communication skills as a fundamental element of case formulation and building a productive working alliance between ECP and patient.

Research suggests that an integrated approach to teaching consultation skills increases student confidence and competence, reinforcing the notion of ‘patient-centredness’ and professionalism.42 It is also widely recognised that communication skills need to be taught, practised and given the same emphasis as other core competencies.43

Studies of communication skills training for junior doctors suggest that, while some basic skills may be learnt experientially (for example, showing courtesy, appropriate eye contact, avoiding jargon), there is still a need for applied skills training. Such training needs to address areas such as initiating the consultation discussion, structuring the interview, giving information, making transitional statements, good questioning skills and developing rapport.44

While less extensive research has been carried out in eye care professions, greater recognition has been given to the need to systematically train optometry students in specific interpersonal skills45 while good patient communication is regarded as an important skill for ECPs, particularly for new practitioners.46

Could specific communication training help with the identification and management of CLD? A recent systemic review of allied healthcare practitioners noted preliminary and indirect evidence of a positive influence upon clinician performance and patient outcome with specific training based around effective practice and delivered using practical modalities 47

With such potential to get training just right, industry and clinical stakeholders could be encouraged to work together in pursuit of a bespoke communications training approach, tied to some specific clinical outcomes for the improved identification and management of CLD.

Is it possible to argue that nascent communication skills in university vision science departments and ongoing CET for ECPs is already sufficient? One study of patient-centred communication among optometry students noted a number of aspects of verbal communication that were consistent with a patient-centred model. Paradoxically, the study also identified the presence of countering verbal strategies that challenged this ethos, such as closed questions, technical language or jargon.48

Failing to acknowledge an adaptive problem, such as CLD, will make it harder to achieve the goals for reducing discomfort. Therefore, ECPs would benefit from explicit training on how to talk with and about CLD with their patients.

Can we leave communication skills development to an employer or professional education? Comparative studies between allied healthcare practitioners and optometry students49 have found the latter may have greater difficultly in embracing ambiguity and complexity. Newly qualified ECPs have been found to focus more on personal deficit, where not knowing is more a sign of failure than progress and there exists a distrust of acknowledging uncertainty. In other helping professions, there is more of a professional ‘signature’ towards uncertainty, making it routine to seek guidance, accept criticism, know limits, and regard development of competence as an ongoing and key part of the role. This suggests that training ECPs in adaptive problem solving, TLTM subjective assessments and Socratic methods may be of benefit, overall and for the identification, management and treatment of CLD.

Optometrists may also feel less confident of succeeding with emotional and angry patients and relatives, breaking bad news and managing their time with the patients and further studies may be needed to explore person-centred communication in optometric practice.6,50

Conclusion

In summary, if good communication is a prerequisite for good quality in person-centred health care,51,52 then ways to build upon the self-efficacy of ECPs in how they work with patients to achieve mutual goals is important.47,51 The approach to communication in the context of CLD pushes the expectations to include higher order skills in the way conversations work in practice.

The process required for ECPs to navigate the challenge of uncovering and managing CLD includes the idea of a working alliance, being comfortable with the ambiguity of an adaptive problem, looking for the existence of traces, by listening for what is not being said as much as what is being said, assessing what might remain hidden from view in sub-clinical signs.

By working out what is too little or too much, we can work out what is just right. Further, by knowing that what is just right also changes, means learning and adapting becomes central to an ongoing dialogue. This draws the ECP and patient together as characters into new chapters of their story. A story where, hopefully, Goldilocks is less disruptive, all the bears feel happier and fewer things are broken or spoiled.

Andy Cole is a Business Psychologist and Executive Coach. His consulting practice covers organisational development, coaching, corporate education, and experiential leadership development. His career started in human resources for the UK police service and rail industry. He held senior leadership roles in learning and professional education with Dollond & Aitchison. He is actively involved in promoting mental health and wellbeing, both in the workplace and in private life. He is an addiction therapist and a Trustee of the addiction organisation, ATSAC.

References

- https://www.bcla.org.uk/Public/News/Blog_Posts/Pioneers-lecture-to-focus-on-contact-lens-discomfort.aspx

- Kern J, Rappon J, Bauman E, Vaughn B. Assessment of the relationship between contact lens coefficient of friction and subject lens comfort. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013 Jun 16;54(15):494-.

- Stapleton F, Tan J. Impact of contact lens material, design, and fitting on discomfort. Eye & Contact Lens: Science & Clinical Practice. 2017 Jan 1;43(1):32-9.

- http://www.bmgresearch.co.uk/general-optical-council-contact-lenses/

- https://www.optical.org/download.cfm?docid=9C3A4787-BB26-47AF-B47CFAF5ADCD6840

- Bulpin C, Cole A, Ewbank A. Gesprächsführung in der Praxis: eine Einführung.

- Cole, A. (2019). Breaking bad news. Optometry Today, 59(1), 67–70

- Wick, R. E. (1970). Communication as an optometric technique. Optometry and Vision Science, 47(9), 720-728.

- Mocheria S, Raman U and Holden B (2011) Clinician-Patient Communication in a Glaucoma Clinic in India. Qualitative Health Research 21(3):429-440

- Jackson, J. L. (2005). Communication about symptoms in primary care: impact on patient outcomes. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 11(supplement 1), s-51.

- Nichols JJ, Willcox MD, Bron AJ, Belmonte C, Ciolino JB, Craig JP, Dogru M, Foulks GN, Jones L, Nelson JD, Nichols KK. The TFOS international workshop on contact lens discomfort: executive summary. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013 Oct 1;54(11):TFOS7-13.

- Papas EB, Ciolino JB, Jacobs D, Miller WL, Pult H, Sahin A, Srinivasan S, Tauber J, Wolffsohn JS, Nelson JD. The TFOS International Workshop on Contact Lens Discomfort: report of the management and therapy subcommittee. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2013 Oct 1;54(11):TFOS183-203.

- https://www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife/jacques-derrida/

- Fylan F. Communicating confidently. Optician 2011;242:6319 30

- Millington A. Patient-centred consultation. Optician June 13 2008;18-22.

- Moss R (2013) Focus on lenses: new products and technologies to make dispensing and communicating the benefits of lenses to patients easier will be a major feature of this year’s Optrafair. Optometry Today 53(6):26

- McMonnies CW. Improving patient education and attitudes toward compliance with instructions for contact lens use. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2011;34:5 241-8.

- Morgan S. How can we influence CL wearers to take our advice? Optician 2013;245:6387 20-24.

- Heifetz RA, Heifetz R. Leadership without easy answers. Harvard University Press; 1994.

- Aron DC. Dealing with Complex Systems. InComplex Systems in Medicine 2020 (pp. 217-227). Springer, Cham.

- Zhu P. Systems thinking vs. systemic thinking vs. systematic thinking. http://futureofcio.blogspot.com/2015/01/systems-thinking-vs-systemic-thinking.html. 22 Mar 19.

- Servant-Miklos VF. Problem solving skills versus knowledge acquisition: The historical dispute that split problem-based learning into two camps. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2019 Aug 1;24(3):619-35.

- Cole SA, Bird J. The Medical Interview E-Book: The Three Function Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013 Dec 14.

- Schutz W. The interpersonal underworld. Palo Alto, Calif.: Science & Behavior Books; 1958.

- Mocheria S, Raman U and Holden B (2011) Clinician-Patient Communication in a Glaucoma Clinic in India. Qualitative Health Research 21(3):429-440

- Cunningham JM. Review of Nonverbal communication: Notes on the visual perception of human relations and Disturbed communication: The clinical assessment of normal and pathological communicative behavior.

- Ambady N, Bernieri FJ, Richeson JA. Toward a histology of social behavior: Judgmental accuracy from thin slices of the behavioral stream. InAdvances in experimental social psychology 2000 Jan 1 (Vol. 32, pp. 201-271). Academic Press.

- Ambady N, Hallahan M, Conner B. Accuracy of judgments of sexual orientation from thin slices of behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1999 Sep;77(3):538.

- Ambady N, Weisbuch M. Nonverbal behavior. Handbook of social psychology. 2010 Feb 15;1:464-97.

- https://www.aop.org.uk/ot/cet/2020/07/06/cet2-does-body-language-communicate-personality/article

- Vergauwe J, Wille B, Hofmans J, Kaiser RB, Fruyt FD. The too little/too much scale: A new rating format for detecting curvilinear effects. Organizational Research Methods. 2017 Jul;20(3):518-44.

- Cropley DH, Harris MB. 7.2. 3 Too Hard, Too Soft, Just Right… Goldilocks and Three Research Paradigms in SE. InINCOSE International Symposium 2004 Jun (Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 1450-1465).

- Balas-Timar D, Lile R. The story of Goldilocks told by organizational psychologists. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2015 Aug 26;203:239-43.

- Kaiser RB, Kaplan RE. Overlooking overkill? Beyond the 1-to-5 rating scale. People and Strategy. 2005 Jul 1;28(3):7.

- https://positivepsychology.com/socratic-questioning/

- Beck, A.T., & Dozois, D.J. (2011). Cognitive therapy: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Medicine, 62, 397–409.

- James, I.A., Morse, R., & Howarth, A. (2010). The science and art of asking questions in cognitive therapy. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38(01), 83–93.

- Neenan, M. (2008). Using Socratic Questioning in Coaching. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 27(4), 249-264.

- Reuman L, Buchholz JL, Blakey SM, Abramowitz JS. Cognitive change via rational discussion.

- Padesky CA. Collaborative case conceptualization: Client knows best. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2020 Jul 23.

- THOMPSON, B., Collins, M. J., & HEARN, G. (1990). Clinician interpersonal communication skills and contact lens wearers’ motivation, satisfaction, and compliance. Optometry and vision science, 67(9), 673-678.

- Papageorgiou A, Miles S, Fromage M, et al (2011) Cross-sectional evaluation of a longitudinal consultation skills course at a new UK medical school. BMC Medical Education 11(1):55-55

- Kuehl SP (2011) Communication Tools for the Modern Doctor Bag. Physician Patient Communication Part 1: Beginning of a medical interview. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 1(3)

- Aspegren K and Lønberg-Madsen P (2005) Which basic communication skills in medicine are learnt spontaneously and which need to be taught and trained? Medical Teacher 27(6):539-543

- Thompson, B. M., & Lovie-Kitchin, J. E. (1988). Interpersonal skills training for optometry students: What should be taught. Optometric Education, 13, 84-88.

- Challinor D (2011) Developing good communication. Optometry Today 51(19):8

- Parry R. Are interventions to enhance communication performance in allied health professionals effective, and how should they be delivered? Direct and indirect evidence. Patient education and counseling. 2008 Nov 1;73(2):186-95.

- Hildebrand, J. M. (2007). Talking with and about older adult patients: The socializing power of patient-centred communication in an optometry teaching clinic (Master’s thesis, University of Waterloo).

- Spafford, M. M., Schryer, C. F., Campbell, S. L., & Lingard, L. (2007). Towards embracing clinical uncertainty: Lessons from social work, optometry and medicine. Journal of Social Work, 7(2), 155-178.

- Sundling, V., Hafskjold, L., Kristensen, D. V., Ruud, I., & Eide, H. Postgraduate Optometry Students’ Person-Centred Communication Skills: The Person-Centred Communication with Older Persons in Need of Health Care (COMHOME) Study.

- Ammentorp J. Klar tale med patienterne–Spørgeskema 1 til klinisk personale [Clear-cut communication with patients]. Sygehus Lillebælt, Enhed for Sundhedstjenesteforskning. 2012.

- Eide H, Eide T. Kommunikasjon i relasjoner: samhandling, konfliktløsning, etikk. Gyldendal akademisk; 2007.

- Sundling, V., van Dulmen, S., & Eide, H. (2016). Communication self-efficacy in optometry: the mediating role of mindfulness.