Recently there has been increased attention regarding the safety of contact lens (CL) wear during the coronavirus pandemic.1-3 However, there is no scientific evidence of an increased risk of contracting coronavirus through CL wear, nor that wear should be avoided for healthy or asymptomatic individuals.1

Covid-19 is caused by a novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Like other respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV-2 spreads through direct contact (person-to-person transmission) or through bodily fluids.4,5 Examples include droplets from when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks and to a lesser extent, surface transmission. While viral particles could land on the eye and spread to the nose and throat through the tears,6 infection of the eye with SARS-CoV-2 in this way is considered unlikely.7,8 Clinical studies suggest that while SARS-CoV-2 has been found in the tears of some Covid-19 patients, there is a low risk of transmitting the disease through the eye and the proportion of those with viral conjunctivitis is extremely low.9,10

The Covid-19 pandemic has reminded eye care professionals (ECPs) of the importance of infection control and has also highlighted the need to reinforce CL hygiene and compliance to promote successful CL wear (figure 1). Ongoing education of CL wearers is needed irrespective of CL modality, replacement frequency or CL care solution type, to help prevent complications such as microbial keratitis (MK) and corneal infiltrative events (CIEs) and to improve CL comfort, vision and satisfaction.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Currently, there are an estimated 140 million CL wearers worldwide.11 Prescribing patterns differ between countries; however, in the United Kingdom approximately 95% of wearers are prescribed soft CLs, mostly for daily wear.12 Prescriptions for daily disposable (DD) CLs continue to increase around the world, averaging around 58% of lenses prescribed in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2019 (15% hydrogel, 43% silicone hydrogel).12 Approximately 35% of wearers in the UK are still prescribed reusable daily wear CLs (2% hydrogel, 33% silicone hydrogel), which require care and maintenance with CL care solutions. Multipurpose solutions (MPS) continue to predominate in the UK (96%) compared to 4% hydrogen peroxide or other care systems.12

Microbial Keratitis and Corneal Infiltrative Events

While CLs lenses are successfully worn by millions of wearers and the risk of CL-related corneal infection is thankfully rare, MK remains the most serious complication of CL wear, due to its potential to cause scarring and loss of vision. CIEs are less severe in nature but can still disrupt CL wear and lead to temporary or permanent discontinuation.

Despite the introduction of new soft CL materials, designs and care systems, epidemiology studies have shown that the rates of MK in daily and extended wear have remained consistent over the last few decades.13,14 The annualised MK incidence rate is approximately two to four per 10,000 wearers in daily soft lens wear and 20 to 25 per 10,000 wearers in extended wear.13,15 Incidence estimates of Acanthamoeba keratitis are approximately 20 per million lens wearers in the UK.16,17 CIEs are much more common, occurring in up to 26% of reusable soft lens wearers, with approximately 2.5 to 6% of CIEs being symptomatic or more severe.18

However, some improvements have been seen with DD lenses, with less severe infections and vision loss reported,13 and certain DD materials appear to be protective against MK.19,20 CIE rates in DD lenses are also significantly reduced, with less than 0.5% CIEs observed in a large post-market registry study of over 1,000 hydrogel and silicone hydrogel DD wearers.21

These MK and CIE data are predominantly from studies of adults. As more children are being fitted with myopia control CLs, there is a need to further understand the safety of CLs in children and adolescents. To date, comprehensive, prospective epidemiological studies of MK rates in children worldwide have not been conducted; however, valuable insights from several published studies suggest no increased risk of MK or CIEs compared to adults.22-24 Recently, in a three-year study evaluating MiSight 1 day lenses for myopia control in children aged eight to 12, there were only four asymptomatic CIEs (one MiSight 1-day, three Proclear 1-day control) and no cases of MK.25

MK and CIE Risk Factors

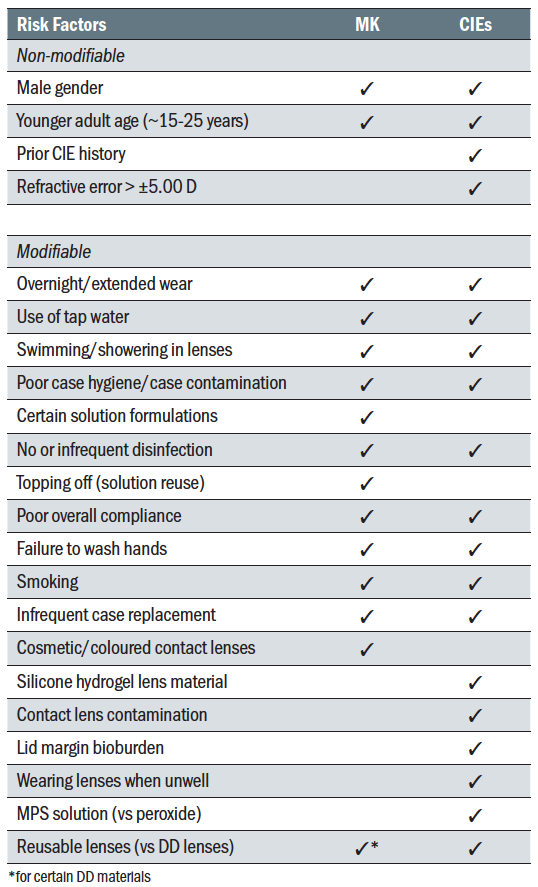

MK and CIE studies have consistently identified a number of significant non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors (table 1). Many risk factors are common to both MK and CIEs, including male gender, smoking, younger adult age (approximately 15-25 years old), extended/overnight wear, tap water exposure, failing to wash hands, poor case hygiene and infrequent case replacement. Understanding these risk factors, especially those that are modifiable, can help ECPs implement patient strategies to minimize risk and improve patients’ CL wear experience.

Table 1: Summary of commonly reported risk factors for MK and CIEs in CL wear13,15,19,20,22,26-35

Table 1: Summary of commonly reported risk factors for MK and CIEs in CL wear13,15,19,20,22,26-35

The Role of Lens Care Solutions and Cases

Although CL care solutions undergo standardised regulatory testing before being marketed, a number of care systems have been found to increase the risk of MK or Acanthamoeba keratitis, including heat, chlorine, certain MPS formulations, and oxipol.15,30,31,36

In 2006-2007, Fusarium and Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreaks resulted in the global recalls of ReNu MoistureLoc (Bausch + Lomb) and Complete MoisturePlus (AMO) MPSs. Solution reuse (topping off, or adding fresh solution to old solution),37 solution evaporation37,38 and temperature instability39 were found to contribute to enhanced Fusarium growth in biofilms in ReNu MoistureLoc cases. Components of the Complete MoisturePlus formulation were found to promote encystment (the resistant form) of Acanthamoeba.40 In addition, high risk behaviours such as solution reuse, lack of rubbing CLs and showering with CLs were associated with increased risk of Acanthamoeba keratitis.41

These global outbreaks highlighted the need for Acanthamoeba and more ‘real world’ regulatory testing standards to be developed and new International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) standards for testing CLs in lens cases with solutions,42 as well as Acanthamoeba encystment,43 were published in 2014 and 2015, respectively. An ISO standard for testing disinfection solution efficacy against Acanthamoeba trophozoites is currently under development.

As mentioned in table 1, CL case contamination and poor case hygiene have also been found to be significant risk factors for CL-related MK13,15 and CIEs.33 The clinical significance of case contamination cannot be overstated. Up to 80% of CL cases become contaminated with bacteria, fungi, yeasts and/or Acanthamoeba, as early as seven days after use,44-46 and up to 2.5 million (6.4 log) colony forming units of microbes per storage case well have been isolated from two-week old cases.47 Several studies have also isolated identical microorganisms from corneal ulcers and the corresponding cases.48-50

In a 12-month, prospective, case-control study,15 poor storage case hygiene and infrequent storage case replacement increased the risk of moderate to severe MK by 6.4x and 5.4x, respectively. The authors concluded that almost 50% and 27% of moderate and severe MK cases could be eliminated by better case hygiene (primarily air-drying lens cases) and frequently replacing lens cases at least every three months, respectively. Overall, combined attention to just case hygiene and replacement would result in a 62% reduction in MK disease load.15

A number of compliance issues have been found to be associated with case contamination. Solution reuse/topping off, not rinsing the lens case after discarding the used solution and using tap water to rinse the lens case have all been found to increase the risk of case contamination.44-46 Other non-compliant behaviours increasing case contamination are failure to wash hands, contamination of the care solution bottle tip and not using the lens case supplied with the disinfecting solution.44,46

Being preservative-free, hydrogen peroxide systems can provide several benefits compared to MPSs including reduced solution-induced corneal staining and improved comfort in patients who are sensitive to preservatives.51 It has been suggested that compliance with hydrogen peroxide solutions is greater than with MPSs, particularly for using fresh solution each time lenses are disinfected and replacing the lens case as recommended.51 However, from an efficacy perspective, case contamination studies have found that MPS and one-step peroxide solutions have similar rates of contamination and one-step peroxide cases can show higher levels of contamination than MPS cases.47

The Role of Contact Lenses

It is also important to consider the role of modality, replacement schedule and material on MK and CIEs. As mentioned previously, extended/overnight wear of soft CLs increases the risk of MK and CIEs by 4-5x. This includes if lenses are only worn occasionally overnight (≤ 1 night per week).13 Overnight wear of rigid gas permeable (RGP) lenses, such as for orthokeratology, also results in higher rates of infection than daily wear RGP lenses.52

When DD lenses are worn on a purely DD basis in compliance with the recommended wear and replacement schedule (ie no cases, solutions or extended wear), the risk of MK is approximately halved and infections are less severe,13 but additional epidemiology studies are needed to confirm this reduced incidence rate. Elimination of the CL case in DD wear is likely to play a significant role, as there is a lower likelihood of isolating environmental organisms (which would usually be found in contaminated lens cases) from corneal cultures in DD infections.20 Certain DD materials also appear to be protective against MK;19,20 however, further research is needed to understand what material and mechanical properties, and/or design features, reduce the risk of infection.

When compared to DD lenses, reusable lenses have been shown to have a 12.5x greater risk of CIEs, irrespective of lens care solution used.53 Reusable silicone hydrogel lenses also have a two times greater risk of CIEs compared to hydrogel materials.54 However, this material effect on CIEs has not been observed in DD lens wear, where both material groups show very low CIE rates of less than 0.5%.21 These data highlight the need for continued rigor in providing good education on lens wear and care, particularly for reusable lenses.

There have also been increasing reports of the risks of MK with cosmetic or coloured CLs, especially in Asian countries.32,55 These infections may be related to purchasing cosmetic lenses from unregulated sources or sharing of lenses between individuals.55 Rates of MK appear to be higher in cosmetic lens wearers, but further studies are needed to accurately determine the incidence rates compared to clear lenses.

Reducing Risk and Enhancing Compliance

Taking an evidence-based approach to reducing complications, one clear strategy is to eliminate cases and solutions altogether by prescribing DD lenses. As we have discussed, DD lens wear reduces exposure to environmental pathogens resulting in less severe infections, less chance of vision loss and very low CIE rates. However, overnight wear and not washing and drying hands have been identified as risk factors in DD MK.20 Therefore, education in these areas is still important for DD wearers. For reusable CL wearers who are being refitted in DD lenses, additional advice on why solutions and lens cases should not be used is also recommended, to discourage reverting back to previous habits.

Numerous barriers to prescribing DD lenses have been identified.56 These include cost, ECP habits and patient preference. It is important to remember that patients rely on ECPs to recommend the healthiest CL options for them, without guessing or assuming what they can or cannot afford.

Enhancing compliance through focusing education on high-risk modifiable behaviours, such as sleeping in lenses or use/exposure to water, is another strategy to reduce complications. Explaining how high-risk behaviours can lead to MK and CIEs is important, but it has also been found that a big motivating factor for CL wearers is actually being able to continue to wear their CLs. Reminding CL wearers that high-risk behaviours can lead to discomfort and poor vision, and potentially permanent discontinuation from lens wear, is often more impactful than just talking about the complications that might occur.57

The Health Belief Model

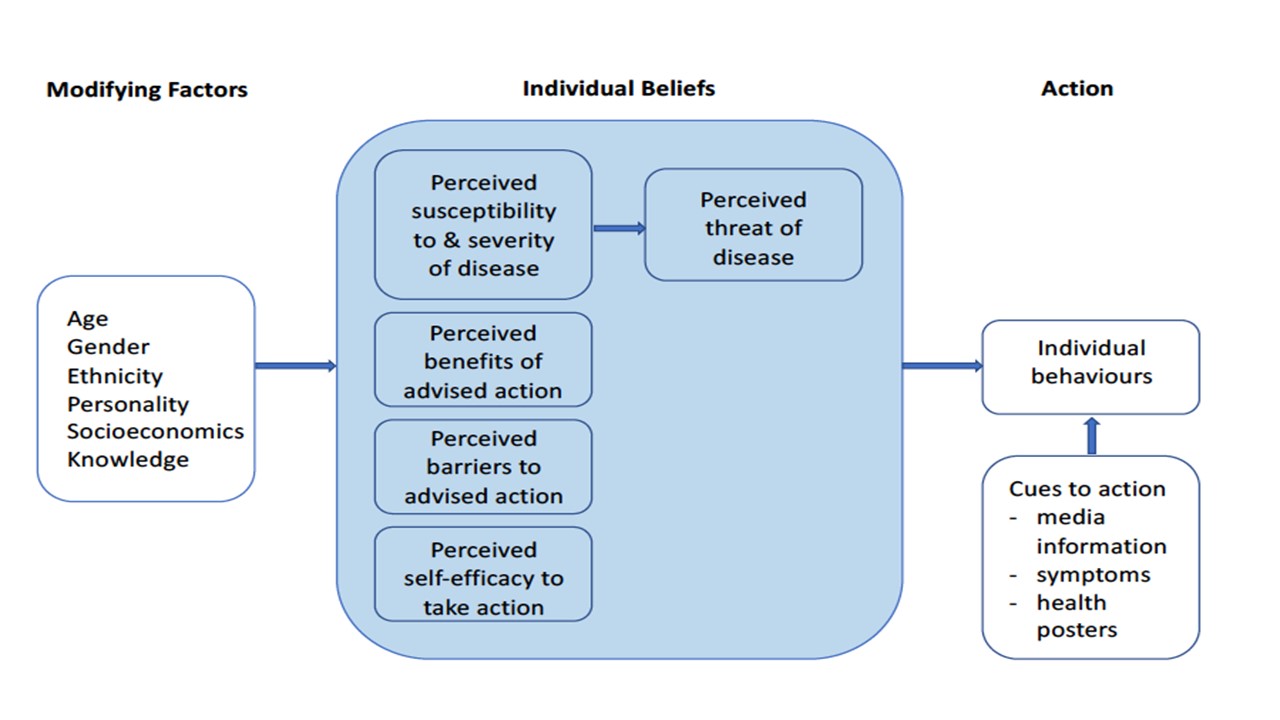

A significant amount of research has been conducted in medicine to understand what drives compliance with instructions provided for health care. The Health Belief Model (figure 2) has taught us that non-compliance is not a passive process or a result of laziness, but relates to patients’ beliefs that health recommendations will be effective, and that they have the ability to carry out the recommended procedures.58,59 Compliance results from a shared partnership between the patient and the practitioner.

Figure 2: Key components of the Health Belief Model59

Figure 2: Key components of the Health Belief Model59

Based on the Health Belief Model, it is important to explain the nature and purpose of each step or patient instruction. For most CL wearers, handling their CLs with wet hands or not rinsing their lens case, does not result in any immediately noticeable difference to their CL wearing experience. Education on ‘why’ as well as ‘how’ is needed to improve compliance. For example, a CL wearer should understand the purpose of washing and drying hands, why CL disinfection is needed, what rinsing the lens case does and just because their case looks clean, it does not mean that it does not need replacing.

A staggering 40 to 80% of medical information provided to patients by healthcare practitioners is forgotten immediately, and almost half what is remembered is incorrect.60 In a recent study conducted in Italy and Japan, new DD CL wearers fitted with lenses approximately eight months prior, were not always able to recall advice from their ECP.61 This appeared to be more prevalent in Japan than Italy, especially for the instructions to not sleep in lenses (53% recall Japan vs 62% Italy, p<0.01), to wash hands with soap and water before handling (43% recall Japan vs 70% Italy, p<0.05) and not to wear lenses for longer than the replacement frequency (47% recall Japan vs 69% Italy, p<0.05).

It is, therefore, important to supplement verbal instructions with demonstration of techniques and written information for the patient to take home. Compliance was found to be two times greater in CL wearers provided with written instructions compared to verbal only.45 In addition, the more information that is presented to a patient, the less that is recalled.60 So it is also helpful to tailor your advice based on individual patient behaviours. Having the patient demonstrate their hygiene and lens care procedures at follow-up visits can help identify the specific areas requiring re-education. With increased prescribing of myopia control CLs, education of parents as well as children is essential to ensure healthy and successful CL wear.

Another way to enhance compliance in reusable CL wearers, is to prescribe the CL care solution along with the CLs on a patient’s prescription. In a recent survey of 33 habitual reusable CL

wearers, only ~40% of subjects reported having a care system recommended by their ECP, yet 91% indicated they would rather have a solution prescribed or recommended by their ECP.62 Prescribing the care solution provides you with an opportunity to explain that it is also a medical device and should not be switched without consulting you. The patient can be educated on why you have prescribed the care system, eg they are atopic or have sensitive eyes and you are prescribing a preservative-free peroxide system. In addition, bundling CLs and solutions for regular shipment may also enhance compliance by reducing the likelihood to switch brands with different active ingredients.

General education about the importance of regular eye examinations is also necessary, even if patients are asymptomatic. Recently, in a study of 202 CL wearers, 72% of asymptomatic CL wearers who attended clinics for routine CL examinations were found to have ocular health, anterior eye, CL fit, and/or non-compliance issues and 4% had signs of undiagnosed systemic diseases.63

Another important way that ECPs can help improve the safety of CL products is to report adverse events appropriately to CL manufacturers and regulatory agencies. This allows for real world data to be collected from patients worldwide and helps identify significant trends, such as the Fusarium and Acanthamoeba keratitis outbreaks discussed previously, that may need to be addressed and can also lead to enhanced product testing standards and the development of improved CLs and care systems.

Useful Advice for CL Wearers and Resources

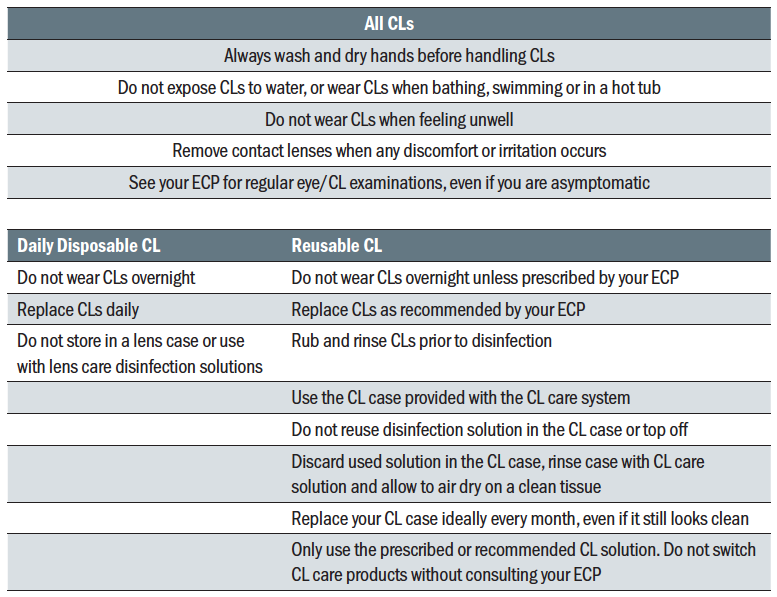

Greater compliance not only reduces the risk of complications, but can result in improved comfort and vision,64 which are

important factors for CL wearer retention.65 A summary of top compliance tips for CL wear and care is provided in table 2.  Table 2: Top tips for compliance with CL wear and care for DD and reusable soft CL wearers

Table 2: Top tips for compliance with CL wear and care for DD and reusable soft CL wearers

There are numerous CL educational resources available for ECPs and CL wearers that can be used in practice as well as through email and social media communication. Here are some of the more useful:

- The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the USA has developed a comprehensive website entitled Healthy Contact Lens Wear and Care (www.cdc.gov/contactlenses), which contains a wealth of evidence-based information and resources for patient education, including videos and posters.

- The British Contact Lens Association (BCLA) has many resources available in the Consumer section of their website; https://bcla.org.uk/Public/Consumer/Public/Consumer/Consumer_Information.aspx?hkey=4c724c75-0b80-4a33-b784-c753d90ec2ad)

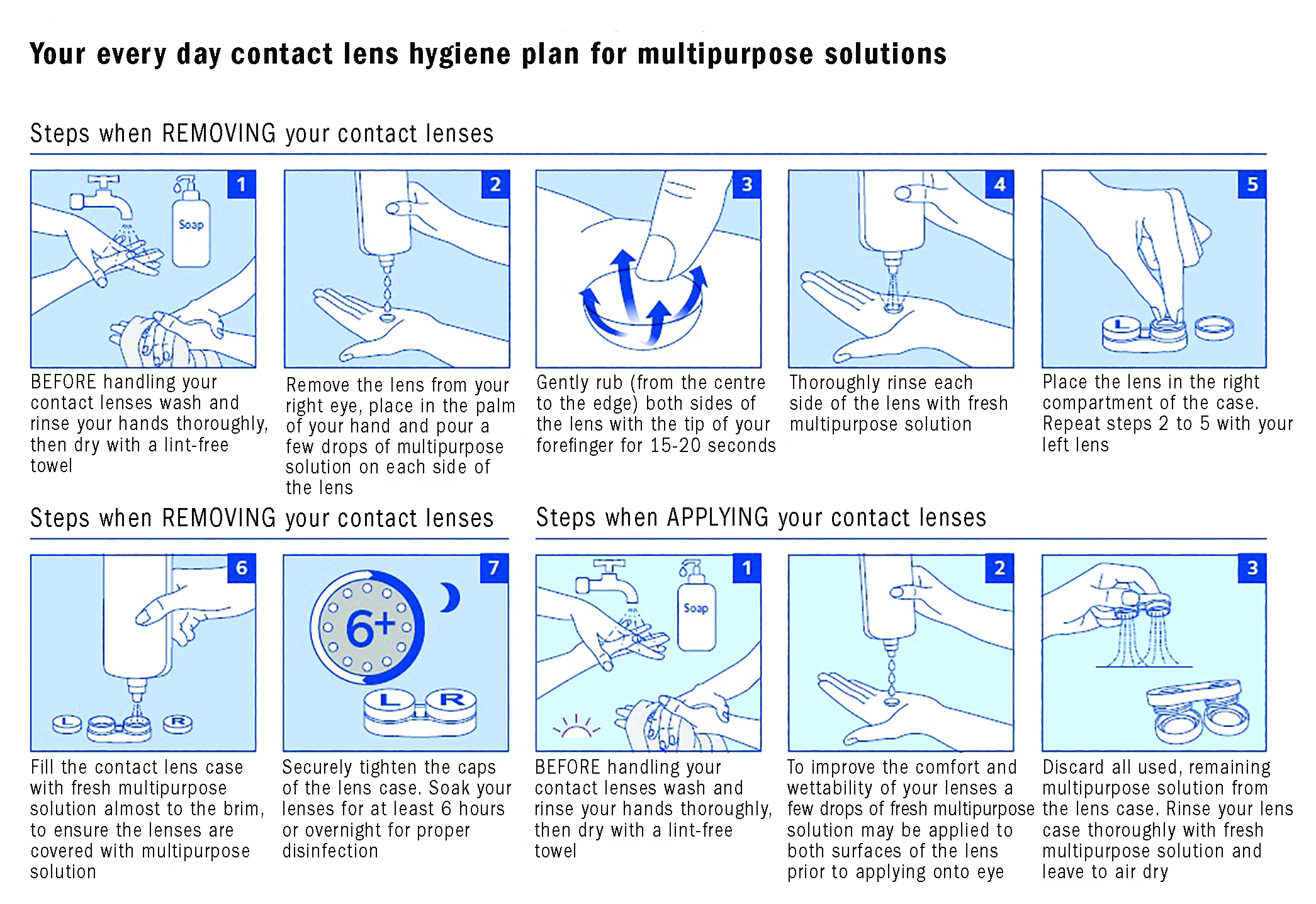

- Several CL manufacturers have also developed content for patient education that can be accessed online (figure 3).

Figure 3: An example of a consumer education resources on compliance with lens wear and care (courtesy of CooperVision and available at; https://coopervision.co.uk/our-products/patient-instruction)

Figure 3: An example of a consumer education resources on compliance with lens wear and care (courtesy of CooperVision and available at; https://coopervision.co.uk/our-products/patient-instruction)

Hand washing

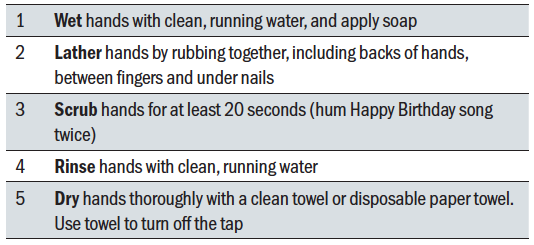

The importance of hand hygiene for CL wearers cannot be emphasised enough and has been recently reviewed.66 If we can identify any positives from the Covid-19 pandemic, it is the effectiveness of the public health messaging and education regarding the importance of, and correct way to, wash and dry hands (see table 3).

Table 3: The five important steps of hand washing based on CDC guidance. Available at; www.cdc.gov/handwashing/when-how-handwashing.html

Table 3: The five important steps of hand washing based on CDC guidance. Available at; www.cdc.gov/handwashing/when-how-handwashing.html

The World Health Organisation website has published clear step by step instructions in a series of images that can be downloaded for use in practice or to provide to patients (www.who.int/gpsc/clean_hands_protection/en). Other initiatives, like World Hand Hygiene Day (www.cute-calendar.com/event/world-hand-hygiene-day/38194.html), can also be leveraged to remind patients of the importance of washing and drying hands for CL wear and general health.

No sleeping/overnight CL wear

As few as approximately 1% of soft CLs are currently prescribed by ECPs for overnight or extended wear in the UK,12 as many ECPs are aware of the increased risks with this modality. Some patients may have occupations that necessitate extended wear, otherwise, daily wear is recommended. Educational materials warning of the risks of overnight wear can be found on many professional websites (for example, www.bcla.org.uk/Public/Consumer/Wearing_contact_lenses_overnight.aspx).

Patient accounts of their own experiences with CLs can also be powerful educational tools. The CDC has published a series of ‘Protect Your Eyes’ videos (www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/videos.html) that can be accessed online, including ‘Te’s Story – Don’t Sleep in Contacts’ (www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYlF92Ou0l4). The CDC also has published a ‘Sleeping in contacts is risky business’ poster designed to be displayed in high visibility areas such as consulting and waiting rooms (www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/pdf/sleeping-8x11.pdf).

No water

In a recent General Optical Council survey in the UK of 2,043 CL wearers, one of the highest levels of non-compliance was using CLs for swimming, hot tubs or water sports without goggles.67 ‘No water’ stickers, designed by a patient who experienced Acanthamoeba keratitis, are available through the BCLA (www.bcla.org.uk/Public/Member_Resources/Professional_Resources/No_Water_Stickers/Public/Member_Resources/No_Water_Stickers.aspx?hkey= c92e88e6-6d31-4784-b0ac-13a3dc9cf153) to remind CL wearers to avoid using water exposure to lenses or cases. The stickers are designed to be placed on CL cases and packaging, and were recently found to significantly reduce overall water exposure behaviours and CL case endotoxin levels when applied to lens cases.68

CDC materials warning against water exposure are also available online and include a poster (www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/pdf/keep-water-away-8x11.pdf) and ‘Ryan’s Story – Water and Contacts Don’t Mix’ patient video (www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_SZmhsYXKk ).

Rubbing and rinsing contact lenses

Rubbing and rinsing reusable CLs is an important step to prepare the CL for disinfection but is often overlooked. When asking patients to explain how they clean their lenses, they will often verbally report rubbing their lenses for 10 or 20 seconds but only actually demonstrate rubbing for a few seconds at most. As we are now all aware that singing the Happy Birthday song takes about 10 seconds, recommending this song for following manufacturer specified rubbing and rinsing times is a useful tip to help patients be compliant.

No solution reuse or ‘topping off’

Reusing old solution or topping off should always be discouraged due to the increased risk of case contamination, MK and Acanthamoeba keratitis.69,70 Reminding patients to discard the solution in the lens case immediately after lens insertion and using analogies such as reusing water for dishes or the same bathwater can be utilised when providing education in this area.71 The CDC also has a downloadable poster available on this topic (www.cdc.gov/contactlenses/pdf/keep-it-fresh-8x11.pdf).

Case hygiene and replacement

There is conflicting information online regarding case care and replacement and procedures also vary by manufacturer. However, in general, following disinfection and lens application, the used solution in the lens case should be discarded, the case should then be rinsed with the CL care solution and air dried, preferably face down on a clean tissue.72 Tap or bottled water should never be used in the care and maintenance of lens cases. Certain care systems may have additional requirements, so it is important to review the manufacturer recommendations for each care system together with the patient.

The BCLA recommends that cases be replaced at least monthly (www.bcla.org.uk/Public/Consumer/Important_dos_and_dont_s_of_contact_lens_wear.aspx). The European Contact Lens Forum (http://media.voog.com/0000/0035/8605/files/DEC2017TRUTHABOUTCL.pdf) recommend case replacement at least every three months. Given that significant levels of case contamination develop after two weeks to one month of use,44,47,73,74 cases should ideally be replaced every month.

Many care solutions provide a new case with every bottle. To avoid stockpiling of cases, it is important to remind patients that just because the case is visually clean, does not mean that it is free of microbes. Cases should be replaced monthly, even if they do not look dirty or damaged.

Conclusions

CLs continue to be a safe form of vision correction worn by millions around the world. CL wear during the Covid-19 pandemic should not be discouraged, if proper care and maintenance procedures are followed and patients are not unwell. To promote healthy and successful CL wear, patients do need to be educated and regularly reminded to practice optimal hygiene and follow ECP instructions.

Education on high-risk behaviours that increase the risk of MK and CIEs should be provided at every visit, including avoiding overnight wear, reusing solutions, use of tap water or wearing CLs when swimming or showering. Review of proper hand-washing and case hygiene procedures are also essential, in particular, air drying the lens case and replacing the case every month.

There are many resources available to ECPs to help support patient education and reinforce compliance, and these can be used to supplement advice given during face to face visits, as well as through email and social media communication with patients between visits. Utilising these resources can help bridge the gaps in understanding between ECPs and patients, and lead to a more successful CL wearing experience.

Professor Carol Lakkis is Adjunct Professor at the University of Houston College of Optometry, Texas and Director, iBiomedical Consulting, Jacksonville, Florida. Anna Sulley is Director, Global Medical Affairs, CooperVision, and Dr Melanie George is a Director of CooperVision Lens Care Research and Development, San Francisco Bay Area, US.

- Professor Carol Lakkis is paid consultant of CooperVision, Inc.

References

- Jones L, Walsh K, Willcox M, Morgan P, Nichols J. The Covid-19 pandemic: Important considerations for contact lens practitioners. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2020;43:196-203.

- Mignucci M. Stop Touching Your Face By Wearing Glasses, Not Contacts. 9 March 2020. Bustle https://wwwbustlecom/p/stop-touching-your-face-by-wearing-glasses-not-contacts-22603755; Accessed 12 March 2020.

- Weiss S. Does wearing glasses help protect you against coronavirus? 10 March 2020. New York Post; https://nypost.com/2020/03/10/does-wearing-glasses-help-protect-you-against-coronavirus/: Accessed 10 March 2020.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020;Jan 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

- Guo YR, Cao QD, Hong ZS, et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) outbreak – an update on the status. Mil Med Res 2020;7:11.

- Zhou L, Xu Z, Castiglione GM, Soiberman US, Eberhart CG, Duh EJ. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed on the human ocular surface, suggesting susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ocul Surf 2020.

- Willcox MD, Walsh K, Nichols JJ, Morgan PB, Jones LW. The ocular surface, coronaviruses and Covid-19. Clin Exp Optom 2020;103:418-24.

- Lange C, Wolf J, Auw-Haedrich C, et al. Expression of the Covid-19 receptor ACE2 in the human conjunctiva. J Med Virol 2020;10.1002/jmv.25981. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25981.

- Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol 2020;Feb 26. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25725. [Epub ahead of print].

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;Feb 28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [Epub ahead of print].

- Hui A. Where have all the contact lens wearers gone? CL Spectrum 2019;34 July:22-7.

- Morgan PB, Woods CA, Tranoudis IG, et al. International contact lens prescribing in 2019. CL Spectrum 2020;35 January:26-32.

- Stapleton F, Keay L, Edwards K, et al. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia. Ophthalmology 2008;115:1655-62.

- Stapleton F, Carnt N. Contact lens-related microbial keratitis: how have epidemiology and genetics helped us with pathogenesis and prophylaxis. Eye (Lond) 2012;26:185-93.

- Stapleton F, Edwards K, Keay L, et al. Risk factors for moderate and severe microbial keratitis in daily wear contact lens users. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1516-21.

- Radford CF, Minassian DC, Dart JK. Acanthamoeba keratitis in England and Wales: incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;86:536-42.

- Ibrahim YW, Boase DL, Cree IA. Factors affecting the epidemiology of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2007;14:53-60.

- Szczotka-Flynn L, Jiang Y, Raghupathy S, et al. Corneal inflammatory events with daily silicone hydrogel lens wear. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91:3-12.

- Dart JK, Radford CF, Minassian D, Verma S, Stapleton F. Risk Factors for Microbial Keratitis with Contemporary Contact Lenses A Case-Control Study. Ophthalmology 2008.

- Stapleton F, Naduvilath T, Keay L, et al. Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis in daily disposable contact lens wear. PLoS One 2017;12:e0181343.

- Chalmers RL, Hickson-Curran SB, Keay L, Gleason WJ, Albright R. Rates of adverse events with hydrogel and silicone hydrogel daily disposable lenses in a large postmarket surveillance registry: the TEMPO Registry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015;56:654-63.

- Chalmers RL, Wagner H, Mitchell GL, et al. Age and other risk factors for corneal infiltrative and inflammatory events in young soft contact lens wearers from the Contact Lens Assessment in Youth (CLAY) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:6690-6.

- Bullimore MA. The Safety of Soft Contact Lenses in Children. Optom Vis Sci 2017;94:638-46.

- Chalmers R, McNally J, Chamberlain P, Keay L. Estimate of Adverse Event Rates in a Retrospective Cohort Study of Safety of Pediatric Soft Contact Lens Wear: the ReCSS Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2020;61(7):5215. doi:.

- Chamberlain P, Peixoto-de-Matos SC, Logan NS, Ngo C, Jones D, Young G. A 3-year Randomized Clinical Trial of MiSight Lenses for Myopia Control. Optom Vis Sci 2019;96:556-67.

- Steele KR, Szczotka-Flynn L. Epidemiology of contact lens-induced infiltrates: an updated review. Clin Exp Optom 2017;100:473-81.

- Edwards K, Keay L, Naduvilath T, Snibson G, Taylor H, Stapleton F. Characteristics of and risk factors for contact lens-related microbial keratitis in a tertiary referral hospital. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:153-60.

- Arshad M, Carnt N, Tan J, Ekkeshis I, Stapleton F. Water Exposure and the Risk of Contact Lens-Related Disease. Cornea 2019;38:791-7.

- Richdale K, Lam DY, Wagner H, et al. Case-Control Pilot Study of Soft Contact Lens Wearers With Corneal Infiltrative Events and Healthy Controls. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016;57:47-55.

- Lim CH, Carnt NA, Farook M, et al. Risk factors for contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Singapore. Eye (Lond) 2016;30:447-55.

- Stapleton F, Dart JKG, Minassian D. Risk factors with contact lens related suppurative keratitis. CLAO J 1993;19:204-10.

- Lim CHL, Stapleton F, Mehta JS. A review of cosmetic contact lens infections. Eye (Lond) 2019;33:78-86.

- Bates AK, Morris RJ, Stapleton F, Minassian DC, Dart JKG. ‘Sterile’ corneal infiltrates in contact lens wearers. Eye 1989;3:803-10.

- Cope JR, Collier SA, Nethercut H, Jones JM, Yates K, Yoder JS. Risk Behaviors for Contact Lens-Related Eye Infections Among Adults and Adolescents - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:841-5.

- Morgan PB, Efron N, Brennan NA, Hill EA, Raynor MK, Tullo AB. Risk factors for the development of corneal infiltrative events associated with contact lens wear. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:3136-43.

- Carnt N, Hoffman JM, Verma S, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: confirmation of the UK outbreak and a prospective case-control study identifying contributing risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102:1621-8.

- Levy B, Heiler D, Norton S. Report on testing from an investigation of Fusarium keratitis in contact lens wearers. Eye Contact Lens 2006;32:256-61.

- Kilvington S, Powell CH, Lam A, Lonnen J. Antimicrobial efficacy of multi-purpose contact lens disinfectant solutions following evaporation. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2011;34:183-7.

- Bullock JD, Warwar RE, Elder BL, Northern WI. Temperature instability of ReNu With MoistureLoc: a new theory to explain the worldwide Fusarium keratitis epidemic of 2004-2006. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1493-8.

- Kilvington S, Heaselgrave W, Lally JM, Ambrus K, Powell H. Encystment of Acanthamoeba during incubation in multipurpose contact lens disinfectant solutions and experimental formulations. Eye Contact Lens 2008;34:133-9.

- Joslin CE, Tu EY, Shoff ME, et al. The association of contact lens solution use and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:169-80.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 18259:2014 Ophthalmic optics – Contact lens care products – Method to assess contact lens care products with contact lenses in a lens case, challenged with bacterial and fungal organisms.https://www.iso.org/standard/61901.html.

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 19045:2015 Ophthalmic optics – Contact lens care products –Method for evaluating Acanthamoeba encystment by contact lens care products.https://www.iso.org/standard/63807.html.

- Lakkis C, Anastasopoulos F, Terry C, Borazjani R. Temporal development of contact lens case and contact lens contamination during daily wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2009;32:224-5.

- Tilia D, Lazon de la Jara P, Zhu H, Naduvilath TJ, Holden BA. The effect of compliance on contact lens case contamination. Optom Vis Sci 2014;91:262-71.

- Wu YT, Willcox MD, Stapleton F. The effect of contact lens hygiene behavior on lens case contamination. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92:167-74.

- Dantam J, McCanna DJ, Subbaraman LN, et al. Microbial Contamination of Contact Lens Storage Cases During Daily Wear Use. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93:925-32.

- Wilhelmus K, Robinson N, Font R, Bowes Hamill M, Jones D. Fungal keratitis in contact lens wearers. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:708-14.

- Bowden III F, Cohen E, Arentsen J, Laibson P. Patterns of lens care practices and lens product contamination in contact lens associated microbial keratitis. CLAO J 1989;15:49-54.

- Kilvington S, Larkin DF, White DG, Beeching JR. Laboratory investigation of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J Clin Microbiol 1990;28:2722-5.

- Nichols JJ, Chalmers RL, Dumbleton K, et al. The Case for Using Hydrogen Peroxide Contact Lens Care Solutions: A Review. Eye Contact Lens 2019;45:69-82.

- Bullimore MA, Sinnott LT, Jones-Jordan LA. The risk of microbial keratitis with overnight corneal reshaping lenses. Optom Vis Sci 2013;90:937-44.

- Chalmers RL, Keay L, McNally J, Kern J. Multicenter case-control study of the role of lens materials and care products on the development of corneal infiltrates. Optom Vis Sci 2012;89:316-25.

- Szczotka-Flynn L, Diaz M. Risk of corneal inflammatory events with silicone hydrogel and low dk hydrogel extended contact lens wear: a meta-analysis. Optom Vis Sci 2007;84:247-56.

- Young G, Young AG, Lakkis C. Review of complications associated with contact lenses from unregulated sources of supply. Eye Contact Lens 2014;40:58-64.

- Karpecki P. Aligning practice with perception: Practical approaches ot fitting daily disposable silicone hydrogel contact lenses. Reveiw of Optometry Suppl 2019;February: https://www.reviewofoptometry.com/CMSDocuments/2019/02/0219_coopervisioni.pdf.

- McMonnies CW. Improving patient education and attitudes toward compliance with instructions for contact lens use. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2011;34:241-8.

- Claydon BE, Efron N. Non-compliance in general health care. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1994;14:257-64.

- Champion VL, Skinner CS. The Health Belief Model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health behavior and health education. 4th edition ed. San Francisco, CA, USA.: John Wiley & Sons; 2008:45-65.

- Kessels RP. Patients’ memory for medical information. J R Soc Med 2003;96:219-22.

- CooperVision Inc. Data on file 2020. Online survey with ECPs (n=100) & new DD SiHy wearers (n=149). Feb/March 2020. Italy and Japan.

- CooperVision Inc. Data on file 2020. Clinical evaluation of 2 FRP CLs and 3 care regimens. Baseline questionnaire n=34.

- Chen EY, Myung Lee E, Loc-Nguyen A, Frank LA, Parsons Malloy J, Weissman BA. Value of routine evaluation in asymptomatic soft contact lens wearers. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2020;Mar 4:S1367-0484(20)30032-1. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2020.02.014.

- Dumbleton K, Woods C, Jones L, Richter D, Fonn D. Comfort and vision with silicone hydrogel lenses: effect of compliance. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87:421-5.

- Dumbleton K, Woods CA, Jones LW, Fonn D. The impact of contemporary contact lenses on contact lens discontinuation. Eye Contact Lens 2013;39:93-9.

- Fonn D, Jones L. Hand hygiene is linked to microbial keratitis and corneal inflammatory events. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2019;42:132-5.

- Turner M. BMG Research GOC 2015 Contact Lens Survey. https://wwwopticalorg/downloadcfm?docid=2206F69C-AD0F-4403-B8761DAB5F69329F 2016.

- Arshad M, Carnt N, Tan J, Stapleton F. Compliance behaviour change in contact lens wearers: a randomised controlled trial. Eye (Lond) 2020.

- Ahearn DG, Zhang S, Stulting RD, et al. Fusarium keratitis and contact lens wear: facts and speculations. Med Mycol 2008;46:397-410.

- Carnt N, Stapleton F. Strategies for the prevention of contact lens-related Acanthamoeba keratitis: a review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2016;36:77-92.

- Morgan PB, Morgan SL. Enhancing patient experience through improved contact lens compliance. Optician 2017;10 November 2017:18-24.

- Wu YT, Zhu H, Willcox M, Stapleton F. Impact of air-drying lens cases in various locations and positions. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87:465-8.

- Lakkis C, Lakkola S. Antibacterial lens case efficacy during silicone hydrogel daily wear. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2006;29:205.

- Willcox MD, Carnt N, Diec J, et al. Contact lens case contamination during daily wear of silicone hydrogels. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87:456-64.