What is it like to have your eyes tested when you have a hearing impairment? What are the main obstacles and worries? How can optometrists help to overcome these hurdles? These questions are increasingly important as the prevalence of hearing impairment is increasing in our ageing population.1

Background

About 35% of people with a hearing impairment experience difficulty with communication, and 32% experience problems when explaining and discussing health issues with health care professionals.2 Discomfort, stress and misunderstanding are common features mentioned by patients with a hearing impairment receiving health care.3,4 Interpreters and deaf oralist speakers greatly improve health care experiences for deaf patients, but these professionals are not always present during eye examinations. For patients with acquired hearing impairment due to ageing, this may not be an appropriate solution as this group tends to communicate through spoken language.4 It is, therefore, important that optometrists are equipped to adapt their communication as appropriate to an individual patient’s situation and preferences.

It has been shown that deaf awareness training can positively impact effective communication in a clinical setting.5 Indeed, Ramaja recommends training optometry graduates in sign language to improve communication between the deaf patient and the practitioner.6 This article serves as an introduction to deaf awareness with a particular focus on communication in the optometric practice.

Facts and statistics

Hearing impairment is common among the elderly. Around 71% of people over the age of 70 are affected.7 With an ageing population, the prevalence of sight impairment8 and hearing impairment2 are expected to increase.9 For sight impairment, data can be collected from the registration statistics for sight impairment and severe sight impairment. Such data are not available for hearing impairment. Around 945,000 people across Scotland are thought to have hearing impairment or deafness (figures from Action on Hearing Loss Scotland), and Bezuijen classifies hearing impairment as follows:2

- Acquired hearing loss later in life. Around 350,000 people in Scotland are affected. It is more common in the older age group.2,10

- Profound deafness at birth or in early years with British Sign Language (BSL) as first language. Scotland counted 12,533 BSL users in 2011.11 This is around 0.2% of the population.

- Profound deafness at birth or in early years not using BSL.

- Acquired profound deafness (deafened).

- Deaf-blind. There are around 390,000 deaf-blind people in the UK with an expected increase to 600,000 by 2035.12

It is clear from these statistics that hearing impairment is something that eye care professionals (ECPs) will continue to encounter on a daily basis. ECPs need to be aware that patients with a hearing impairment have a disadvantage in terms of accessing oral communication. Therefore, it is prudent to adapt the routine depending on the category of patients one is dealing with.

For Sign Language users, an interpreter may be required for communication. Others may prefer an oral interpreter or note taker.13 The majority of deaf patients have acquired hearing loss and largely rely on hearing aids and lip-reading.

The next section describes some general principles to facilitate communication with people with a hearing impairment. More specific advice for different communication preferences will be discussed in later sections.

Top tips for communication with people with hearing impairment

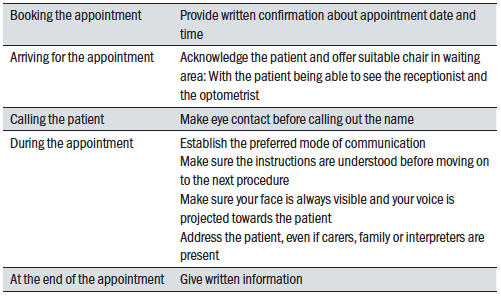

Table 1 outlines some helpful ways of adapting behaviour and practice to maximise effective communication with those attending eye care practice with a hearing impairment.

Table 1: Communication tips for patients with hearing impairment attending the optometric practice

Table 1: Communication tips for patients with hearing impairment attending the optometric practice

It is important to be aware of a patient’s hearing impairment at the beginning of the assessment and to establish the preferred mode of communication. In some cases, the practice may already be aware of the hearing impairment before the patient attends and it is good practice to highlight hearing impairment on the case notes along with the preferred mode of communication for future visits.

It is extremely important to greet the patient, even if one feels unsure about the best way of communication. A smile and a wave can make a huge difference in terms of making the patient feel at ease. Remember that patients attending for an eye examination can feel apprehensive. When there is an added element of anxiety because of the communication barriers, the practice staff need to be even more proactive in making sure that the patient feels welcome and cared for. Patients with a hearing impairment are often worried that they may not hear their name being called when they are waiting in the waiting room.14

Practice staff can reassure patients by stating that the practitioner is aware of the hearing impairment and will approach the patient when it is their turn. Another way to ensure that communication is as effective as possible is the seating arrangement. Patients with a hearing impairment heavily rely on visual cues for initiating and holding a conversation.

Facial expressions, mouth patterns and body language are best seen when there is no light source directly behind the person who is speaking or signing. It is important to look at the person when talking, so that the practitioner’s face is visible at all times. Avoid clutter around the face. Scarfs, hands and hair can all obstruct a clear view. Avoid talking while writing in the case notes or looking down to case notes or away to a computer screen. Walking around during a conversation can also render it difficult for a patient to follow what is being said. Switching the light off during a consultation or obstructing someone’s view with a phoropter, trial frame, slit lamp, fundus camera or other equipment is a major barrier for communication (figure 1). It is therefore important to explain the procedure while the lights are still on prior to carrying out the procedure.  Figure 1: Obstructing a patient’s view of your face with a phoropter is a major barrier for communication

Figure 1: Obstructing a patient’s view of your face with a phoropter is a major barrier for communication

One also needs to explain what is expected from the patient and how the patient can continue to communicate once the procedure has started. This helps to put the patient at ease and facilitates better communication and outcomes. It is generally good practice to provide written information to patients at the end of a consultation and this is even more important in this patient group.

As mentioned before, different patients have different preferences in terms of mode of communication. Some patients use BSL as their primary language, others use different forms of signing and gesturing. The majority use a combination of adapted speech and lip reading. The different communication methods are discussed in the next sections.

It is worth mentioning at this point that the UK government announced a special exemption for wearing face coverings during the Covid-19 pandemic for those who ‘are speaking to or providing assistance to someone who relies on lip reading, clear sound or facial expressions to communicate.’15 Practitioners need to assess individual situations and act in the best interest of each patient. One could consider wearing and offering a face shield to allow a clear view of the face while offering protection (figure 2) and, at the time of writing, the UK government is making clear face masks available to NHS trusts in order to help health and care workers to communicate with people with hearing loss.

Figure 2: A face shield may afford some protection while still allowing facial expression to be visible

Figure 2: A face shield may afford some protection while still allowing facial expression to be visible

Hard of hearing

People with age-related hearing loss primarily communicate through spoken word and/or hearing aids.4 However, patients with age-related hearing loss do not always have or wear appropriate hearing aids. A study by Gregory et al showed this is particularly common among people with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.16

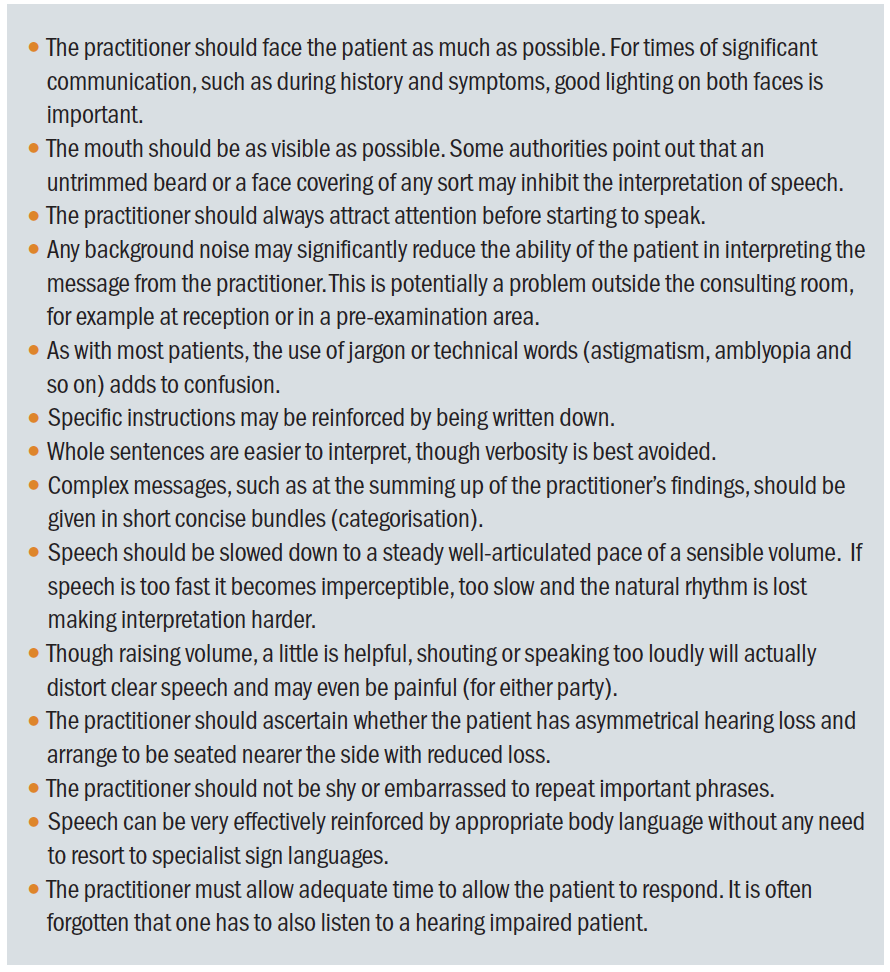

There is a clear need to optimise the use of hearing aids to improve communication. But even when appropriate hearing aids are worn, communication can be compromised to some extent. When a patient is hard of hearing, the usual method of communication is an adapted form of verbal communication. One can make adjustments according to preferred ear and preferred pitch, tone and volume. Patients often find it helpful when a practitioner speaks a little bit slower, but not too slow. It is important to raise the voice without shouting as this can intimidate a person, especially when it is unintentionally accompanied by an angry facial expression. The patient with hearing loss needs to be able to see the practitioner’s face clearly at all times during the consultation as mentioned in the previous section. The voice is easier to pick up when the communication partner is facing the person with hearing impairment. It may be necessary to sit quite close to the patient, especially when hearing loss is accompanied by sight loss, although this may not be possible during the pandemic. Table 2 summarises some of these strategies.

Table 2: Summary of communication strategy for hearing impaired patients

Table 2: Summary of communication strategy for hearing impaired patients

Hearing impairment and cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment and hearing loss are often combined.17-23 Optometrists are likely to encounter patients with combined hearing and cognitive impairment, which causes further barriers for communication. In addition to the communication strategies for people with a hearing impairment alone, further strategies can enhance communication with this group of patients. Marcus gives the following tips to facilitate communication with a person with cognitive impairment:24

- Make contact with your conversation partner before you start talking.

- Ask one thing at a time.

- Use closed questions if you need the person to carry out a concrete action.

- Give compliments.

- Use concrete language (ie avoid symbolic language and expressions).

- Allow the person to divert and gently bring the conversation back to the main topic, even if the information is incorrect. This helps the person to feel at ease.

- Repeat yourself, using different wordings.

- Give someone time to react as spoken language is processed at a slower rate.

- Support your communication with gestures.

- Avoid stress by creating a peaceful and calm atmosphere.

Patient-centred care includes making people feel valued and respected. This is equally important for people with dementia. Alsawy et al found that communication can be enhanced by emotionally connecting with the person and empowering the person’s ability to communicate by actively listening and attempting to understand the person and empathise with the person.25 If the person is accompanied by a relative, friend or carer, one needs to ensure that the patient remains the centre of the conversation and is part of the conversation. The Alzheimer’s society website provides further advice and strategies for communication with people with dementia.26

Signing and lip reading

Profoundly deaf people usually rely on signing or lip reading or a combination of both. Signing is also used by people with a learning disability who experience difficulties in using spoken language. Signing, lip reading and the use of gestures and

symbols are discussed in this section.

British Sign Language (BSL)

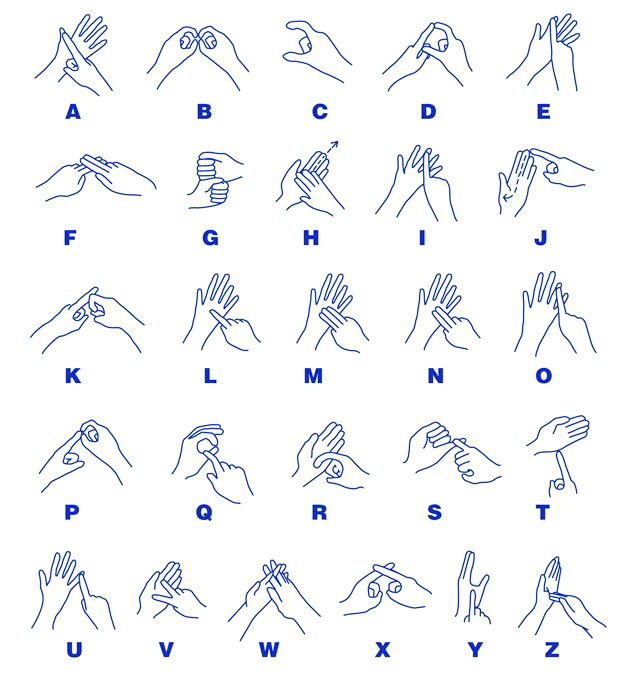

BSL acquired the status of an official language with specific vocabulary, grammar and syntax in 2003.27 It is not strongly related to or dependent upon spoken English. Similar to a spoken language, BSL has regional expressions and accents. One can make up words from single letters by using finger spelling. In BSL, finger spelling is two-handed in contrast with most sign languages, where the signs for individual letters are one-handed. Figure 3 shows the finger spelling alphabet for BSL.

Figure 3: The BSL finger spelling alphabet

Figure 3: The BSL finger spelling alphabet

Knowing this alphabet is helpful when patients are reading out the letters on a letter chart for visual acuity measurement. Finger spelling is also used for spelling people’s names, which is especially useful when introducing the patient to staff in the practice. Finger spelling is a useful tool for those who have a limited vocabulary of signs. A combination of signs, mouth patterns, facial expressions and spacial placement of signs and actions form the language that is known as BSL.

Sign language is distinctly different from gesturing.28 Gestures are typically used alongside spoken language and vary widely between individuals. Signs are used to represent specific vocabulary within a given sign language. Signs can be similar, but are often different between different sign languages. Gestures are a useful communication tool for a person who is unfamiliar with BSL and who wants to communicate with a deaf person. The author has a limited BSL vocabulary and uses a combination of finger spelling, signs, mouth patterns, gestures, facial expressions, pointing and enactment to communicate with deaf people. One can also communicate through writing or typing messages. Written information at the end of the appointment reinforces the key points of the assessment.

Sign-supported English and Makaton

In sign-supported English, a person uses the spoken language (English) accompanied with signs to support the communication. It is used by people with a hearing impairment who still rely partially on verbal communication. These signs are based on BSL. It is also used by people with a learning disability.

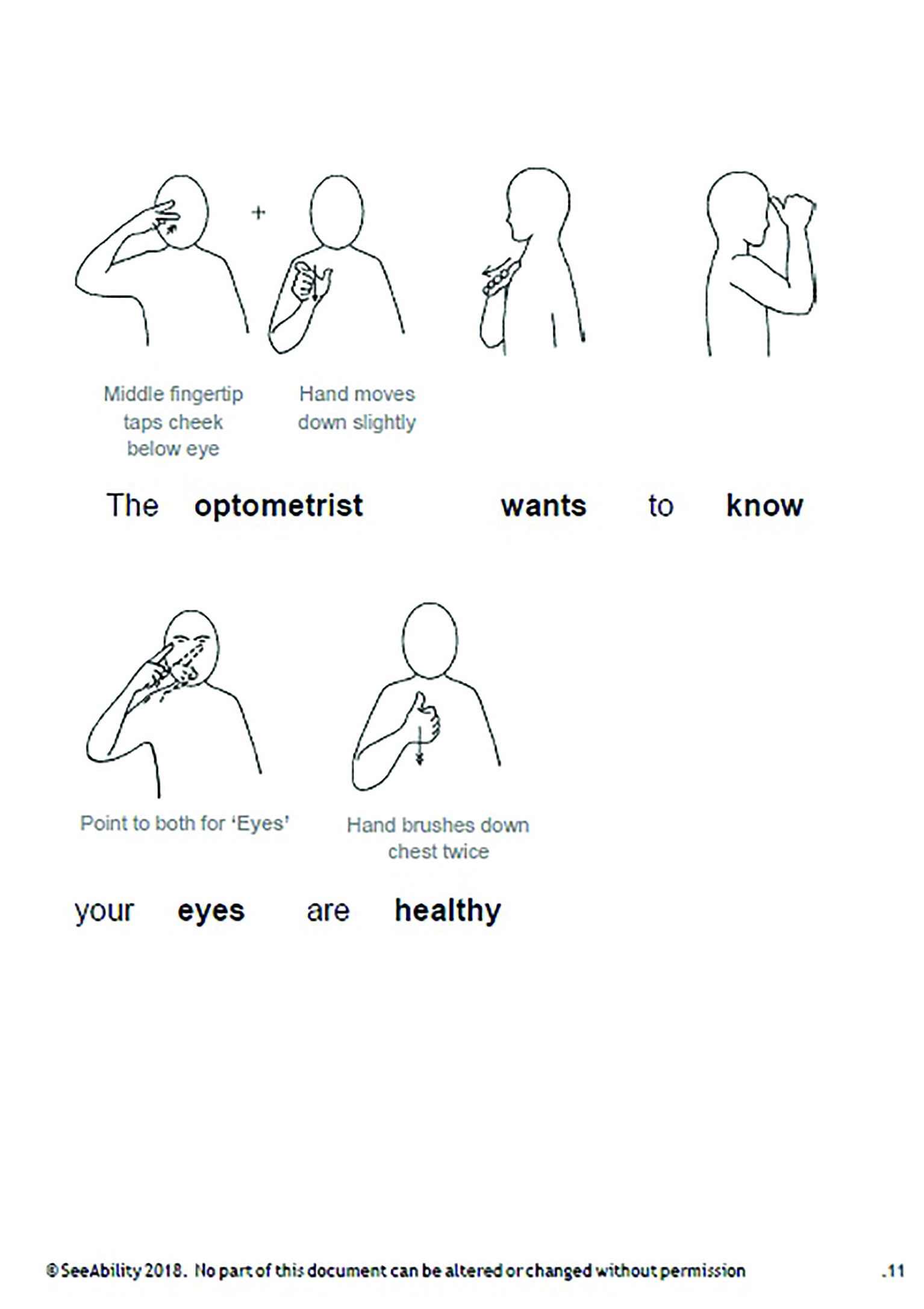

Communication can be further facilitated by the use of graphic symbols. This is known as Makaton. This mode of communication was originally developed in Britain and uses a combination of manual signs, graphic symbols and speech. It is used by people with a learning disability and a variety of other language and communication difficulties.29,30 For children using Makaton, it can be helpful to give a copy of the symbols used in acuity testing prior to the appointment to prepare the child for the sight test. The symbols used in the Kay Picture acuity test all have simple, widely used and understood Makaton signs. SeeAbility’s website is a useful resource for optometrists with an interest in learning Makaton.31 Figure 4 shows some examples of graphic symbols used in Makaton and taken from the SeeAbility ‘Understanding your eye test for Makaton users.’31

Figure 4: Some examples of Makaton symbols31

Figure 4: Some examples of Makaton symbols31

Lip readers

Some profoundly deaf patients rely solely on lip reading. It is especially important for this group that the mouth is visible at all times. Lip readers sometimes use a note-taker to ensure that all the information is written down.

Using an interpreter

BSL users are sometimes accompanied by an interpreter. If there is no interpreter or note taker, one needs to be creative in finding ways to communicate. It is acceptable to use gestures or to use enactments. Some people feel more comfortable to use pen and paper to communicate. When no interpreter is available, the practice could investigate if this service can be used in future appointments, for example through Language Direct.32

Figure 5: The SeeAbility ‘Understanding your eye test for Makaton users’31

Figure 5: The SeeAbility ‘Understanding your eye test for Makaton users’31

One needs to ask the patient what type of interpreter is desired (note taker or BSL). If the patient comes in with an interpreter, one needs to make sure that the interpreter faces the patient and that the patient can see the optometrist’s face at the same time. This allows the patient to observe facial expressions and keeps the patient at the centre of the consultation. The practitioner should address the patient rather than the interpreter, so that the patient can pick up on facial expressions, body language and mouth patterns. In order to keep the flow of the conversation, spoken language needs to be concise and easy to understand. After each short phrase, the interpreter needs time to relay this information to the patient. For refraction and vision, it can be helpful to think about adapting the routine. With a trial frame on, it is harder for the patient to see the interpreter. One can use taps on the arm to indicate which lens is better. One can also use ‘thumbs up’ and ‘thumbs down’. For those who deal with deaf BSL users more frequently, it may be useful to learn the finger spelling alphabet and a few basic phrases in BSL.

Conclusion

The title of this article is chosen to highlight that people with a hearing impairment rely heavily on visual cues for effective communication. It is a quote from the time the author worked in an ophthalmology clinic in a hospital in the Netherlands with many elderly patients. The lights were switched off for part of the eye examination and when the lights were switched on again, patients often commented, saying ‘now I can see what you’re saying!’ At the time, this seemed a peculiar regional phrase, but perhaps many of these patients had a hearing impairment and struggled to follow the conversation in the dark. The light helped them to see facial expressions, mouth patterns and body language, which improved their communication. Hopefully this article has provided an encouragement to think about communication needs in the optometric practice for people with a hearing impairment.

Cirta Tooth is a low vision specialist practising in Scotland with a special interest in people with sensory and learning impairment.

- The next article will focus upon deaf-blindness and what can be offered to this patient group by the community optometrist and by the specialist low vision practitioner.

References

- Akeroyd, MA et al. 2014. Estimates of the number of adults in England, Wales, and Scotland with a hearing loss. International journal of audiology 53(1), pp.60-61.

- Bezuijen, J. 2016. Deafness in Scotland. Deaf Action. Available at: http://www.deafaction.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Deafness-in-Scotland-A-recent-analysis.pdf

- Sans Lledo AI, Gareia Vallejo R. 2019. Perception of health care received in primary care by people with hearing disability. A qualitative stuy. Revista Rol de Enfermeria 42(6), pp.408-412.

- Middleton A, Niruban A, Girling G et al. 2010. Practice pointer: communicating in a healthcare setting with people who have hearing loss. British Medical Journal 341. Article Number e4672

- Middleton, A. et al. 2010. Preferences for communication in clinic from deaf people: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 16(4), pp. 811-817.

- Ramaja J. 2018. Addition of optional sign language in optometry schools for improved eye care for the deaf. African Vision and Eye Health Journal 77(1). Article Number UNSP a-453.

- Action on hearing loss: Facts and figures. Available at: www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk/about-us/our-research-and-evidence/facts-and-figures [Accessed: 14 Jan 2020]

- RNIB: Key information and statistics on sight loss in the UK. Available at: www.rnib.org.uk/professionals/knowledge-and-research-hub/key-information-and-statistics [Accessed on 21 Jan 2019]

- Gothberg H, Rosenhall U, Tengstrand T et al. 2020. Prevalence of hearing loss and need for aural rehabilitation in 85-year-olds: birth cohort comparison, almost three decades apart. International Journal of Audiology. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1734878

- Davis, A. 1995. Hearing in adults: the prevalence and distribution of hearing impairment and reported hearing disability in the MRC Institute of Hearing Research’s National Study of Hearing. London: Whurr Publishers, 1995, p. 822.

- Cassiopeia Consultancy: Briefing note: 2011 Census data on number of BSL users UKCoD/DAC – project to estimate need, demand and cost of relay services for d/Deaf people in the UK. Available at: http://deafcouncil.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/images/Briefing-note-Census-data-on-number-of-Deaf-people-in-UK.pdf [Accessed on 6 Mar 19].

- Sense. Available at: https://www.sense.org.uk/get-support/information-and-advice/conditions/deafblindness/ [Accessed on 19 Jan 2019]

- Iezzoni, LI et al. 2004. Communicating about health care: observations from persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Annals of Internal Medicine 140(5), pp.456-362.

- Stevens MN, Dubno JR, Wallhagen MI et al. 2019. Communication and healthcare: self-reports of people with hearing loss in primary care settings. Clinical Gerontologist 42(5), pp.485-494

- UK Government. 2020. Face coverings: when to wear one

and how to make your own. Available at: www.gov.uk/

government/publications/face-coverings-when-to-wear-one-and-how-to-make-your-own/face-coverings-when-to-wear -one-and-how-to-make-your-own [Accessed on 14 Aug 2020] - Gregory S, Billings J, Wilson D et al. 2020. Experiences of hearing aid use among patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease dementia: a quantitative study. Sage Open Medicine 8. Article Number 205031212090.

- Alattar AA, Bergstrom J, Laughlin GA et al. 2020. Hearing impairment and cognitive decline in older, community-dwelling adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 75(3), pp.567-573

- Dong SH, Park JM, Kwon OE et al. 2019. The relationship between age-related hearing loss and cognitive disorder. Journal for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology Head and Neck Surgery 81(5-6), pp.265-273

- Golub JS, Brickman AM, Ciarleglio AJ et al. 2020. Association of subclinical hearing loss with cognitive performance. Journal of the American Medical Association Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 146(1), pp.57-67

- Huber M, Roesch S, Pletzer B et al. 2019. Cognition in older adults with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss compared to peers with normal hearing for age. International Journal of Audiology 59(4), pp.254-262

- Michalowsky B, Hoffmann W, Kostev K. 2019. Association between hearing and vision impairment and risk of dementia: results of a case-control study based on secondary data. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 11. Article Number 363

- Morita Y, Sasaki T, Takahashi K. et al. 2019. Age-related hearing loss is strongly associated with cognitive decline regardless of the APOE4 polymorphism. Otology and Neurology 40(10), pp.1263-1267

- Yurtogullari S, Koean EG, Vural G et al. 2020. The relationship of presbycusis with cognitive functions. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics 23(1), pp.75-81

- Marcus J. 2020. Praten met iemand die dementie heeft. Onze Taal 4, pp.20-22

- Alsawy S, Tai S, McEvoy P et al. 2020. It’s nice to think somebody’s listening to me instead of saying ‘oh shut up’: People with dementia reflect on what makes communication good and meaningful. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 27(2), pp.151-161

- Alzheimer’s Society. 2020. Communicating and language. Available at: www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/symptoms/communicating-and-language [Accessed on 6 Jul 2020]

- British Sign. What is British Sign Language? Available at: www.british-sign.co.uk/what-is-british-sign-language [Accessed on 21 Aug 2020]

- Fenlon J, Cooperrider K, Keane J et al. 2019. Comparing sign language and gesture: Insights from pointing. Glossa- A Journal of General Linguistics 4(1). Article number 2

- Nicola Grove & Margaret Walker. 1990. The Makaton Vocabulary: Using manual signs and graphic symbols to develop interpersonal communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 6(1), pp.15-28.

- Grove N and Dockrell J. 2000. Multisign combinations by children with intellectual impairments: An analysis of language skills. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 43(2), pp.309-323

- Seeability: Looking after your eyes: Information resources for adults and children with learning disabilities. Available at: www.seeability.org/makaton-signs-for-eye-tests [Accessed on 18 Aug 2020]

- Language Direct. 2019. Tips for working with BSL interpreters in medical settings. Available at: www.languagedirect.org/tips-bsl-interpreters-medical-settings/ [Accessed on 15 Jul 2020]