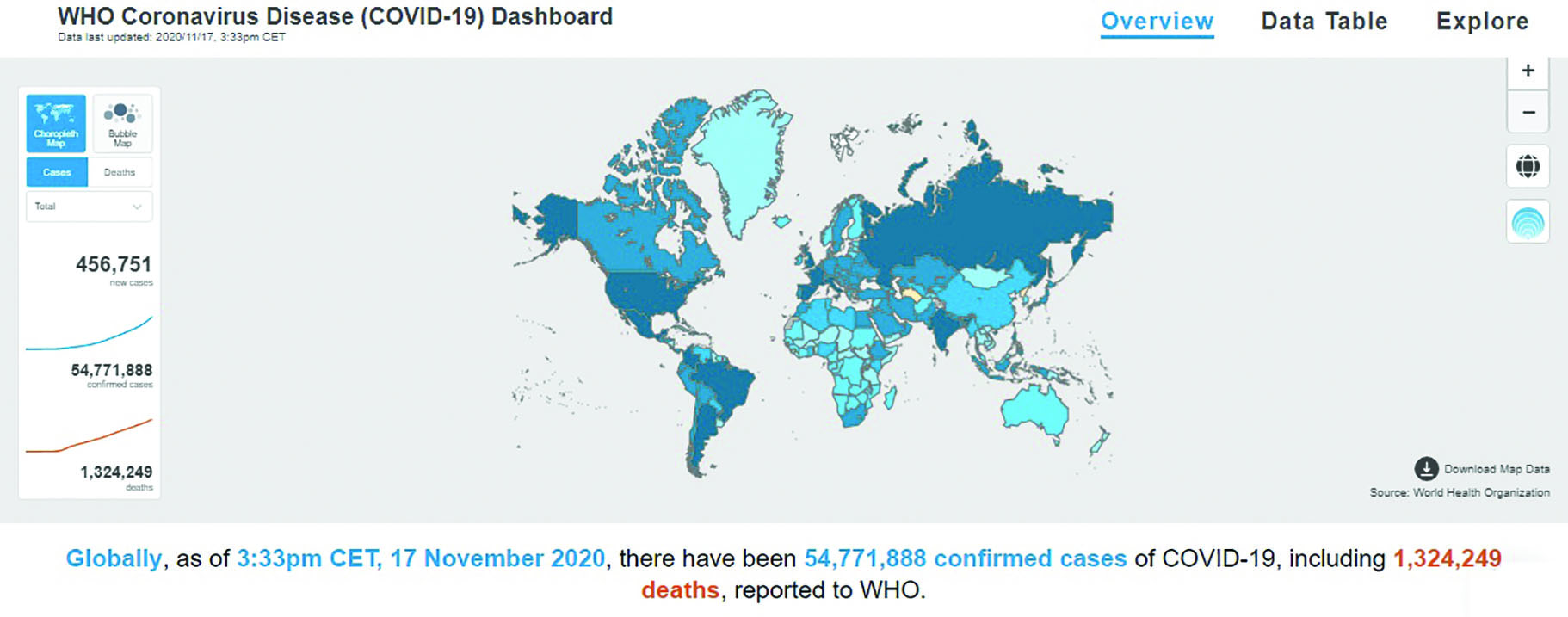

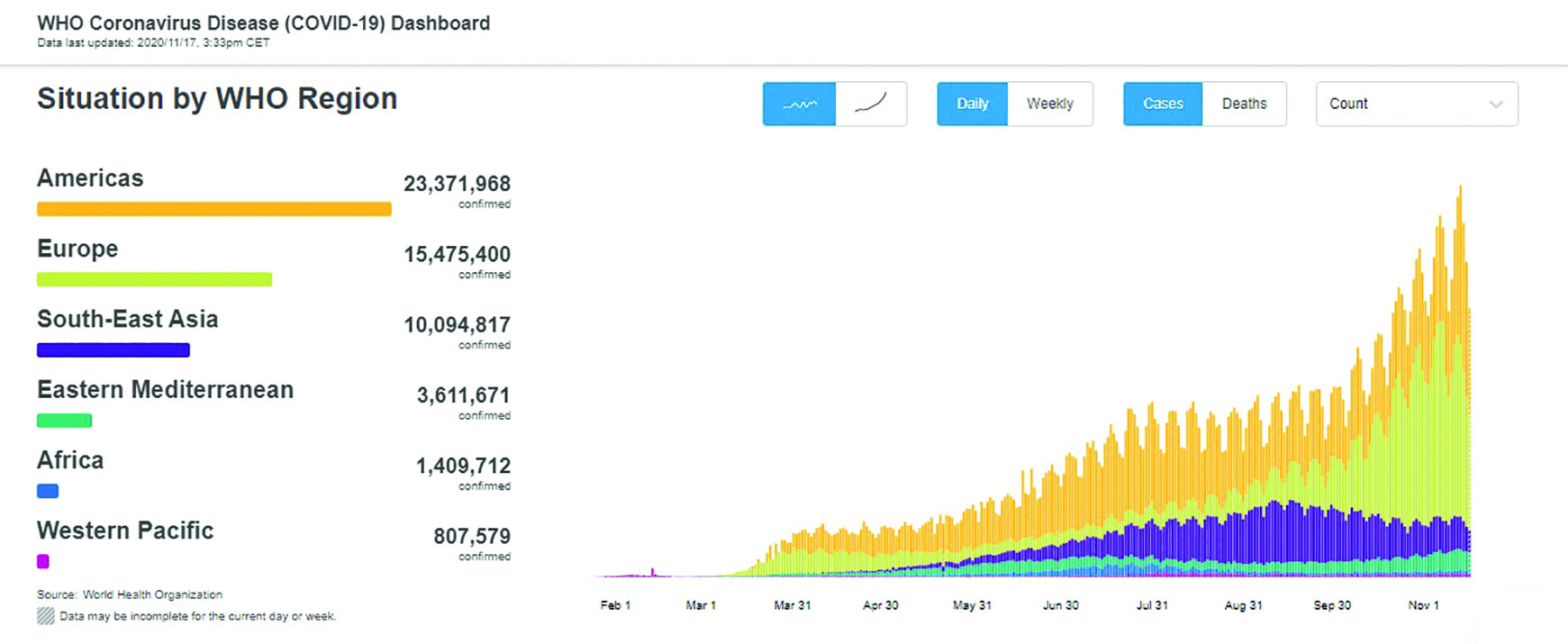

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the highly infectious cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), a disorder which continues to have an unprecedented global impact on public health and health care delivery. Patients with pre-existing conditions are at high risk of further morbidity and mortality from Covid-19 not only during infection but also in the post-infection phase. The latest statistics (at the time of writing) confirm there are nearly 51 million confirmed cases of Covid-19 around the world, with nearly 1.3 million deaths reported so far (figure 1). The greatest number of cases confirmed so far are in the Americas (over 21.5 million cases), followed by Europe (over 13.5 million cases) and south-east Asia (over 9.5 million cases). In the UK, the reported cases have reached a figure of over 1.2 million, with around 50,000 reported deaths by this disease to date (figure 2).

Figure 1: World Health Organization Covid-19 world map

Figure 1: World Health Organization Covid-19 world map

Figure 2: Regional spread of Covid-19 as displayed on the World Health Organisation Covid-19 dashboard 17/11/20

Figure 2: Regional spread of Covid-19 as displayed on the World Health Organisation Covid-19 dashboard 17/11/20

Transmission

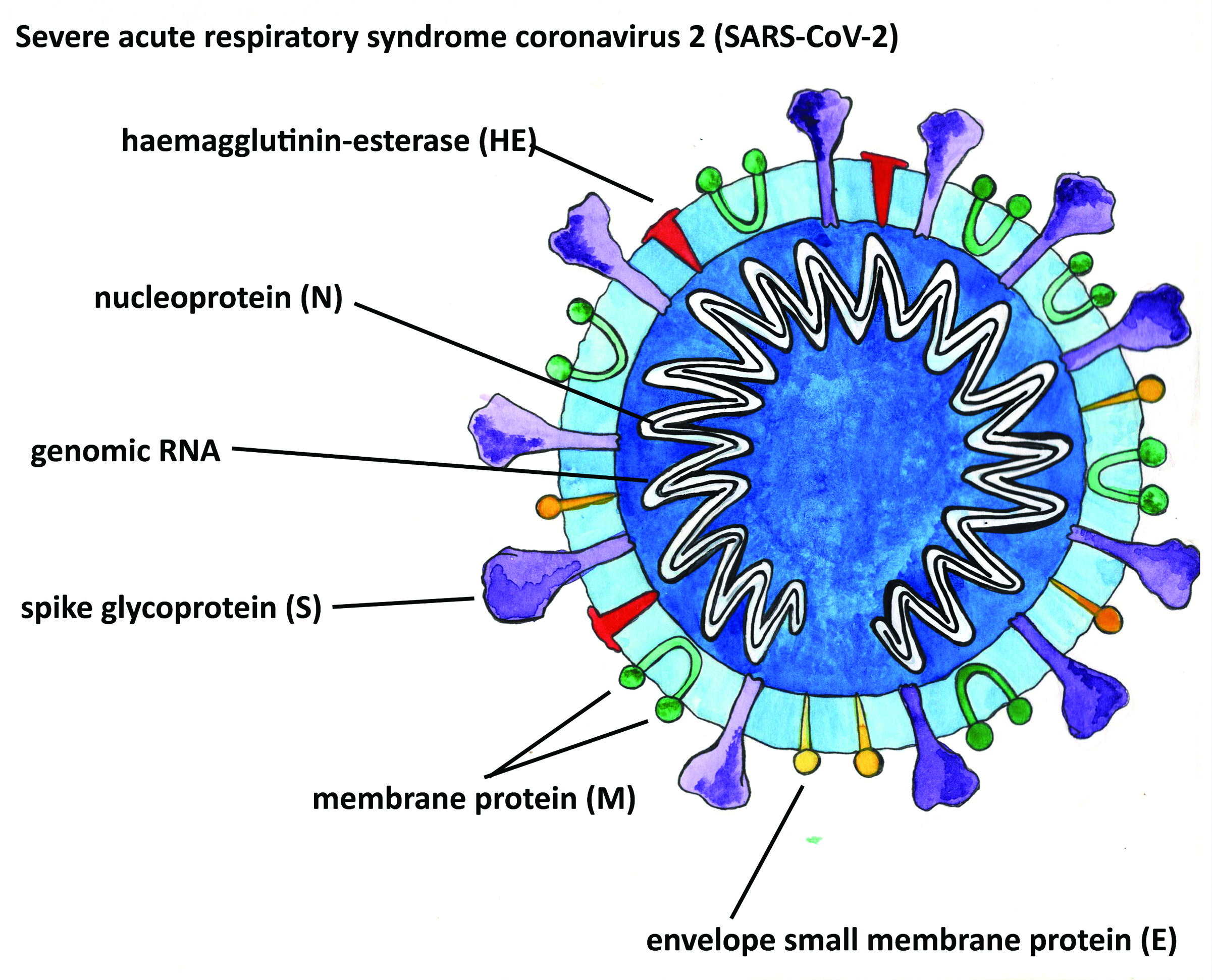

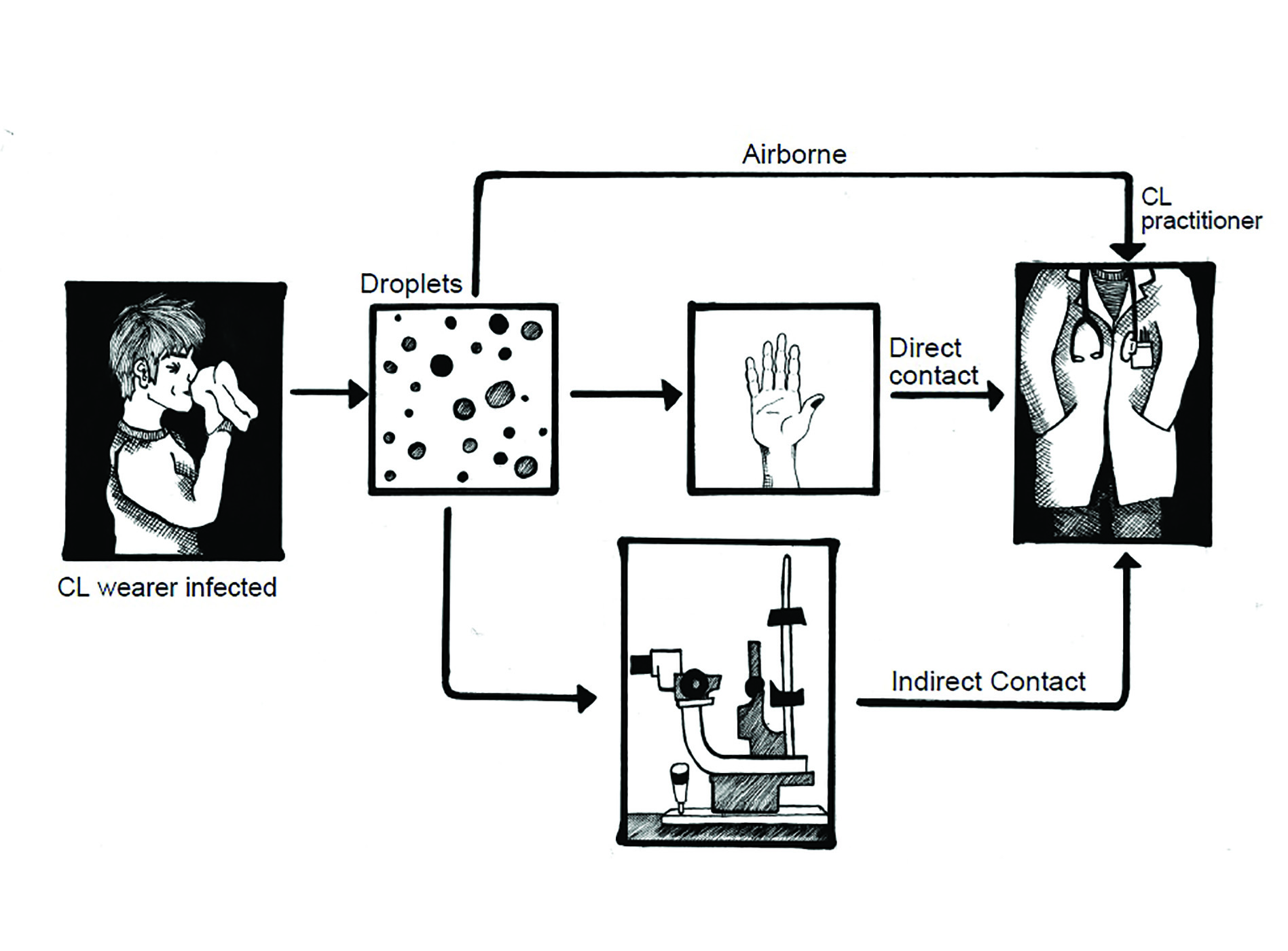

As with any other respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV-2 (figure 3) is transmitted through exhaled droplets from an infected person passing directly onto or into another person, or via particles that are suspended in minute droplets in the air (an aerosol) for a period of time. The later is thought to be a significant route for infection.1 Indeed, in areas with good ventilation and outdoors, the risk of transmission is much lower. In addition, although SARS-CoV-2 can survive on surfaces for days and so be transferred when someone touches the surface, recent research has suggested that this is much less likely route for transmission.2  Figure 3: Structure of SARS-CoV-2 virus (courtesy of Kitty Harvey)

Figure 3: Structure of SARS-CoV-2 virus (courtesy of Kitty Harvey) Figure 4: Potential routes of transmission of virus (courtesy of Kitty Harvey)

Figure 4: Potential routes of transmission of virus (courtesy of Kitty Harvey)

Transmission through direct or indirect contact with the oral cavity, nasal cavity and the ocular surface via mucous membranes has also been advocated3 and, though this mode of transmission has the potential to cause severe disease, SARS-CoV-2 infection or transmission via the ocular surface may, in fact, cause conjunctivitis or other ocular discomfort.4 For a review of the ocular surface response to virus exposure, see Optician 22.5.20. Patients testing positive for Covid-19 have presented with conjunctivitis with the following signs:

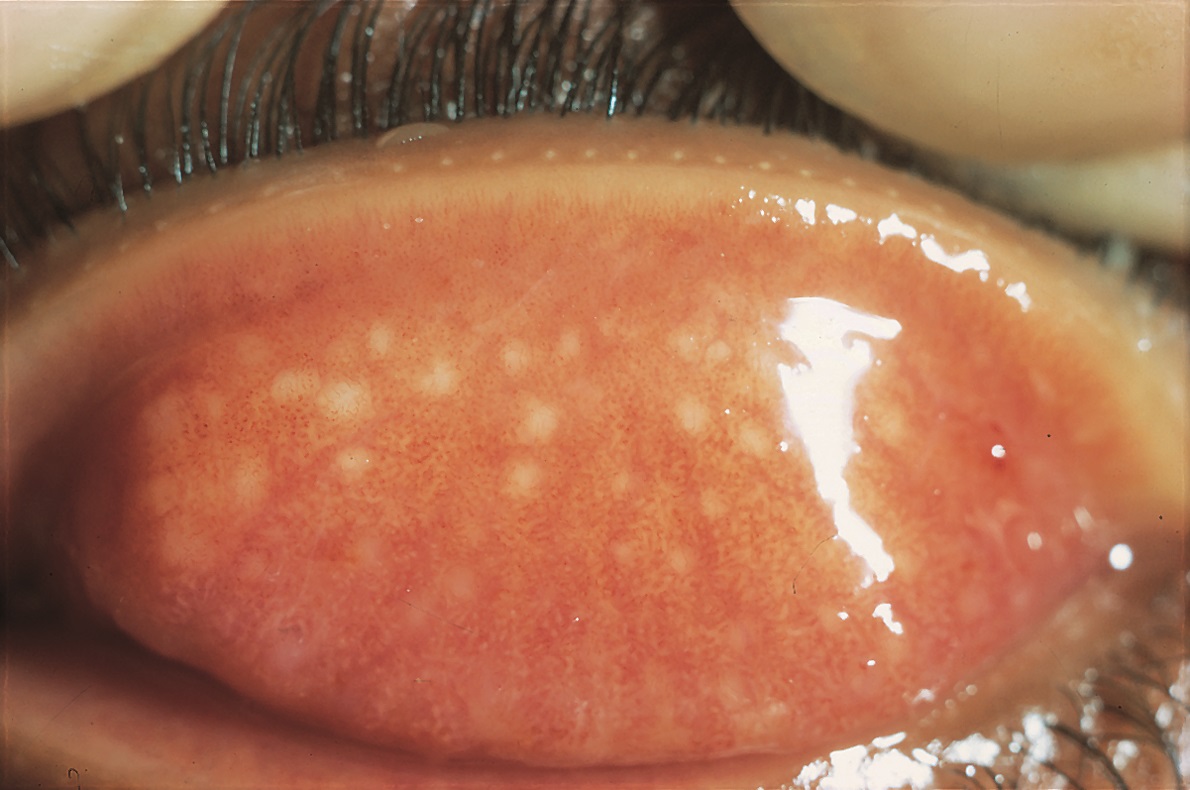

- Mild follicular conjunctivitis (figure 5)

- Watery discharge

- Mild eyelid oedema

Some authors have related the presence of conjunctivitis in Covid-19 positive patients as a warning sign of poor prognosis,5 while others conclude that ocular symptoms are relatively common in Covid-19 and can appear just before the onset of respiratory symptoms.6  Figure 5: Follicles, as seen in viral conjunctivitis, are aggregations of white blood cells and have a pale appearance

Figure 5: Follicles, as seen in viral conjunctivitis, are aggregations of white blood cells and have a pale appearance

Other ocular manifestations linked to Covid-19 include the following:7

- Haemorrhagic conjunctivitis

- Episcleritis

- Anterior uveitis

- Multiple evanescent white dot syndrome

- Atypical optic disc oedema

In addition, ocular shedding of SARS-CoV-2 via the tears is a distinct possibility of which ophthalmologists and optometrists should be aware as this might represent a route for infection when a clinician is required to be in close proximity to the patient.

Safety in clinic

As maintaining appropriate social distancing is near impossible in ophthalmic care, the ocular examination should always be performed while wearing the appropriate protective equipment (figure 6) as recommended by our professional bodies (see Optician 5.6.20 AND 10.7.20), minimise patient contact time and, if possible, employ instrumentation that facilitates examination either remotely or at a greater distance (see Optician 29.5.20).

Figure 6: Personal protective equipment

As professional guidelines during pandemic are constantly under review, readers are reminded of the importance of regular checking in to the latest advice from authorities such as the College of Optometrists,8 General Optical Council,9 ABDO, the AOP and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth).10

Influence of age on COVID-19-related illness

The Covid-19 clinical presentation can vary considerably, some patients showing milder symptoms such as fever, dry cough, and dyspnoea and others developing much more severe disease such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). This is the main cause of death. In addition, the risk of cardiovascular complications and stroke are high in these patients, both during the infection and after.

Ageing has been associated with more severe forms of the disease, mainly because the respiratory system in these patients has a different pathophysiological profile than that of younger individuals. Indeed, there is a decline in the ability to express and clear inhaled particles from the small airways of the lungs, throat and mouth.11 Moreover, the upper airway lumen diameter decreases with increasing age, in both men and women, while men also have a greater upper airway collapsibility than women.12

In addition to the changes in the respiratory system, older patients also suffer from a disruption of both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system with age; a phenomenon termed immunosenescence. They also have higher levels of co-morbidity, with conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity, each of which increases the risk of more severe forms of Covid-19. Moreover, Covid-19 treatments are very aggressive and can have a greater adverse impact on the health and wellbeing of an older patient. Some treatments cause a multitude of ocular side effects. Drugs such as the combination lopinavir-ritonavir are associated with blurred vision, while chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and steroids have effects upon the visual system that are well known and documented (see Optician 24.04.2020).

Pandemic impact on eye care for the elderly

In an effort to stop the spread of infection and protect the vulnerable, the UK government responded by declaring safer-at-home orders and limiting non-essential businesses and access to all medical specialities was restricted (figure 7). Telephone consultation and virtual clinics became the norm, with surgeons managing only elective and urgent surgery and access to healthcare centres was limited to minimise the risk of infection.  Figure 7: The impact of stay-at-home orders has been especially challenging for the elderly

Figure 7: The impact of stay-at-home orders has been especially challenging for the elderly

These measures had a greater impact on older people. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing confirmed that ‘many of the over-50 population were unable to access health care services during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic in England. A sixth of older people report having hospital treatment cancelled, with an additional one in 10 unable to visit or speak to their GP. Access to community health and social care has also been severely disrupted.’13

While the optical professional bodies have given advice aimed primarily at primary care practice,8 the RCOphth have issued guidelines on secondary care, treatments and surgical procedures. A large proportion of these are focused upon vulnerable, older adults, many of whom suffer from age-related ocular and systemic conditions. And while diseases such as exudative AMD, diabetic retinopathy, retinal detachment and advanced/rapidly progressive glaucoma are still on the list of conditions that need to be seen and treated urgently,14 all face-to-face outpatient activities have been postponed except where patients are at great risk of imminent and significant harm. Indeed, referrals to ophthalmology clinics have decrease by around 41%.15 The UK Ophthalmology Alliance also found that up to 50% of people with acute or urgent eye conditions have not been attending appointments during lockdown due to concerns regarding coronavirus.16

However, due to this approach, preventive measures are often overlooked and diseases are being allowed to progress until it may be too late. Telephone consultation and triaging lack precision, especially when dealing with older patients who often underplay their symptoms. The long term harmful impact of the current situation may take a while to become clear, but the burden on the patients’ lives, on the healthcare system and the economy is unlikely to be insignificant.

In some treatment centres, surgical procedures have been categorised as either tier 1, 2 or 3, with tier 1 referring to cataract surgery and tier 3 reserved for urgent or emergency intervention. The risk, however, lies somewhere in between these two, especially with effective management of progressive disorders such as glaucoma. As stated by Professor Peter Netland (Ophthalmology Department, University of Virginia), ‘Treating tier 2 patients is somewhat of a grey zone with glaucoma…tier 3 might mean neovascular glaucoma, and no one questions our treating that. But many patients need surgery because they’re progressing or have pressures that are too high for the condition of their optic nerve. We have to treat those patients within a reasonable period of time. So, we’re still checking those patients in clinic and doing surgery if we need to.’

Residential care homes

The impact of Covid-19 has been devastating on long-term care facilities.17 When dealing with the elderly in residential care, there are a number of challenges presented by the pandemic. These include the isolation resulting from the banning of visits, difficulty understanding safe measures to avoid infection in

people with cognitive impairment, and problems in accessing care.18 To date, there is no data to show the effect of isolation on ocular health and, even in pre-pandemic times, the prevalence of visual impairment and blindness was significantly higher among those living in residential care centres.19 Therefore, it may be that the situation is yet worse since lockdown, with patients being denied basic eye care that could improve not only their vision but also their cognitive and physical wellbeing. With the likelihood of isolation-induced depression also prevalent, the potential for a future health crisis in the elderly is great.

Elderly Visually Impaired

Visually impaired individuals are at a greater risk of clinical depression and socioeconomic difficulty than the general population. In addition, since this group are more likely to have limited social contact and more likely to become isolated, a threat such as Covid-19 will result in much greater increases in levels of anxiety as it is much more difficult for the elderly visually impaired to maintain adequate contact with people or receive adequate care.

As one patient recorded, ‘I don’t have family or friends to help me understand all the changes and new requirements. So, it’s taken me weeks and several hard experiences to figure it out. My anxiety level increases before I even venture out.’20

It was interesting to learn that sight or severe sight impaired patients are not considered ‘clinically, extremely vulnerable’ and therefore miss out on help with their needs and support such as priority home deliveries.21 However, after lobbying by the RNIB, most supermarkets have responded to help prioritise those with sight loss. In addition, social distancing is difficult to judge for the visually impaired, and many have difficulties navigating various barriers and one-way paths newly introduced to previously well remembered routes.24

Dr Lisa Ord, director of the John A Moran Eye Centre Patient Support Program, said recently, ‘Heightened tensions, brought on by fear of the coronavirus, make it more important than ever to be aware that not everyone can see physical barriers or read signs…and public spaces with blocked-off chairs are confusing to guide dogs who may be getting mixed signals – their owners might say one thing, but the barrier prevents the guide dog from moving.’

The Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB) eye clinic liaison officers (ECLOs), in collaboration with eye clinic staff and social services sensory support teams, have worked remotely and tireless to support people with sight loss since the beginning of the pandemic (see Optician 8.5.20).22 In addition, the RNIB offers help and support via dedicated helplines * and can supply products designed to help the visually impaired to cope with challenging conditions.23

The role of community ECPs in supporting elderly visually impaired patients includes ensuring all are aware of the specific needs of these people during these challenging times. Some good tips for helping are included in the document ‘Understanding Covid-19 social distancing challenges for people with vision loss- and how to help,’20 including the following:

- If someone with a white cane or a guide dog seems to be confused or struggling, please do not touch that person or grab an elbow. Just speak up and ask if you can help.

- Remember, they may not want verbal help as it is not private.

- Describe the surroundings. If you are waiting in a line, you can tell the person when the line is moving and verbally guide them to the next marker.

- Describe any barriers (what and where they are) with as much precision as possible. For instance, instead of ‘over there, to your left,’ say ‘two feet to your left’.

- If the person is looking for an empty chair in a waiting area, tell them where it is.

- Are there written signs with instructions or directions present? Let the person know and offer to read the signs to them.

- Remember that masks muffle voices, so speak clearly and slowly. But do not raise your voice unless necessary because of background noise.

- If you are getting on an elevator and there is a passenger limit, let the person know how many people are allowed and if it is OK to enter.

- Tell the patient about the Sunflower Lanyard (available from https://hiddendisabilitiesstore.com) which can be worn to show others why there may be challenges to maintaining social distancing. •

Dr Doina Gherghel is an academic ophthalmologist with a special interest in inter-professional learning for optometrists.

* The RNIB offers a UK-wide Sight Loss Advice Service that can be accessed through a helpline on 0303 123 9999.

References

- https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa939/5867798

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanres/article/PIIS2213-2600(20)30514-2/fulltext

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7262297/

- https://bjo.bmj.com/content/early/2020/08/25/bjophthalmol-2020-316263

- Loffredo L, Pacella F, Pacella E, et al. Conjunctivitis and Covid-19: a meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2020; doi: 10.1002/jmv.25938

- Hong N, Yu W, Xia J, et al. Evaluation of ocular symptoms and tropism of SARS-CoV-2 in patients confirmed with Covid-19. Acta Ophthalmol 2020; doi: 10.1111/aos.14445

- https://www.healio.com/news/ophthalmology/20200812/ophthalmologists-need-to-stay-vigilant-for-ocular-manifestations-of-Covid19?utm_source=TrendMD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=Healio__TrendMD_1- accessed 12 November 2020

- https://www.college-optometrists.org/guidance/Covid-19-coronavirus-guidance-information/Covid-19-college-guidance.html

- https://www.optical.org/en/news_publications/Publications/joint-statement-and-guidance-on-coronavirus-Covid19/index.cfm

- https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/about/rcophth-guidance-on-restoring-ophthalmology-services/rcophth-Covid-19-response/

- Levitzky MG. Effects of aging on the respiratory system. Physiologist. 1984; 27:102–107

- Martin SE, Mathur R, Marshall I, Douglas NJ. The effect of age, sex, obesity and posture on upper airway size. Eur Respir J. 1997 Sep; 10(9):2087-90.

- Covid-19 and disruptions to the health and social care of older people in England. Carol Propper, Isabel Stockton and George Stoye. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/15160

- https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Protecting-Patients-Protecting-Staff-UPDATED-300320.pdf

- https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/news/hidden-backlog-looms-as-nhs-referrals-for-routine-hospital-care-drop

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health‐52968845

- Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a Long-Term Care Facility in King County, Washington. McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, et al. Public Health–Seattle and King County, Evergreen Health, and CDC Covid-19 Investigation Team. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020 May 21; 382(21):2005-2011

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32554346/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22614911/

- https://healthcare.utah.edu/healthfeed/postings/2020/05/social-distancing-with-vision-loss.php

- https://theconversation.com/what-coronavirus-crisis-means-for-blind-and-partially-sighted-people-136991

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/opo.12757

- https://www.rnib.org.uk/sight-loss-advice/Covid-19-five-ways-rnib-services-can-help

- www.rnib.org.uk/news/campaigning/please-give-me-space-social-distance-tool