Currently, work within optical practices largely comprises eye examinations and the dispensing of spectacles. The main aims of the eye examination are to identify signs of eye disease and to help the patient to see as well as they can with the appropriate prescription for vision correction. We are well aware that there are a number of lifestyle factors that will contribute to the ocular and general health of the patient and, most importantly, may well have an influence on future health. This article seeks to explore whether the eye examination as part of a periodic visit to a community eye care practice should be used to provide advice and information regarding lifestyle factors and considers how this might best be accomplished. Also, is it right for eye care practitioners to be doing this?

Health Matters

Many long-term diseases in our population are closely linked to known behavioural risk factors. Around 40% of the UK’s disability adjusted life years lost are attributable to tobacco (figure 1), hypertension, alcohol, being overweight or being physically inactive (figure 2).  Figure 1: Tobacco represents a major risk factor for a wide range of eye and systemic diseases

Figure 1: Tobacco represents a major risk factor for a wide range of eye and systemic diseases Figure 2: Increasing obesity levels are a major factor in

Figure 2: Increasing obesity levels are a major factor in

the increasing level of ill health in the UK

Making changes, such as stopping smoking, improving diet, increasing physical activity, losing weight and reducing alcohol consumption, can all help people to reduce significantly their risk of poor health. We also know there are close links between these lifestyle factors and poor eye health (figures 3 and 4).  Figure 3: Increasing evidence of links between lifestyle choices and eye disease allow better targeted information and advice to be designed

Figure 3: Increasing evidence of links between lifestyle choices and eye disease allow better targeted information and advice to be designed Figure 4: Obesity is the focus of nationwide campaigns

Figure 4: Obesity is the focus of nationwide campaigns

promoting improved eye health in the UK

The concept of community eye care practices taking on a more proactive role in the prevention of poor health fits absolutely with overall health intentions. Over recent years, there have been various strategic initiatives that have set out the need for the promotion of better health and the prevention of disease in a primary care setting. Perhaps the quote that best sums up this is taken from the NHS Five Year Forward View, October 2014:

“If the nation fails to get serious about prevention then recent progress in healthy life expectancies will stall, health inequalities will widen, and our ability to fund beneficial new treatments will be crowded-out by the need to spend billions of pounds on wholly avoidable illness.”

Prevention or Cure?

In the UK, we spend around 20 times more on treating ill health as we do on direct prevention, yet the relative cost-effectiveness equation sees a reversal of these proportions. Prevention of poor health in the primary care setting is likely to be some 24 to 40 times more cost-effective than treatment over the course of a lifetime. A relatively modest shift of investment away from treatments to prevention measures could help to realise a disproportionate benefit in improved population health and significant cost reduction to the NHS and to wider society.

Public Health bodies have the ambition to reduce the impact of unhealthy lifestyles, citing the unwanted costs of smoking as £5.2bn, obesity as £4.2bn and alcohol as £3.5bn. The current NHS Five Year Forward View identifies a need for a more preventative approach to healthcare delivery and proposes a more proactive role for all primary care practitioners. The suggestion is that the promotion of health and wellbeing should be at the core of any health professional’s organisation design and service culture. A significant percentage of visual loss is avoidable, and yet members of the public are largely unaware of the importance of eye health and what actions they should take to improve their own eye health.

The ‘Make Every Contact Count’ initiative, MECC (figure 5), is an approach to behaviour change that utilises the millions of day-to-day interactions that organisations and people have with others to encourage changes in behaviour that will ultimately have a positive effect on the health and wellbeing of individuals, communities and populations. The MECC website provides resources and information to support people and organisations implementing MECC (www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk).

Figure 5: Making Every Contact Count (MECC) is an evidence-based approach to improving people’s health and wellbeing by helping them change their behaviour

At a local level, many counties have set up their own integrated care systems with the core aim of promoting wellbeing, prevention of disease, independence and self-care. The main focus is to prevent illness, disease and frailty, so to enable people to live healthy and independent lives. This includes tackling inequalities in health by targeting support at those individuals and communities where ill-health and the prevalence of unhealthy lifestyles is greatest. Specific mention is made of the need for strengthening primary and community care services to ensure that communities are supported in efforts to stay healthier for longer.

Importance of Eye Health

Looking specifically at our own eye care sector, the UK Vision strategy states: ‘Too many people do not understand the impact of their lifestyle and health conditions on their sight.’ Clearly, eye health is considered to be an urgent public health challenge with significant implications for individuals, society, the economy and beyond. Significant sight loss (SSL), low levels of vision affecting people’s ability to lead normal lives, has a devastating impact, causing isolation, depression and a loss of independence. SSL

currently affects two million people in the UK, with this figure forecast to rise to 4.1 million by 2050.

There is a growing burden on social infrastructure from vision impairment, as eye health is socially very important allowing us to more easily learn, work, travel and engage with other people. Impaired vision leads to a significant reduction in ability to undertake activities important in maintaining social inclusion, making the continuation of mobility, daily living and visually intensive tasks difficult. This can impact upon education, employment, childhood development, mental health, and functional capacity in older people. The social cost of sight loss, and the economic burden of vision impairment, is significant; vision loss costs the UK economy £3 billion a year. This figure rises to around £28 billion per annum when indirect costs are added to the mix.

The impact of sight loss is a significant burden on NHS resources and is predicted to increase. A population of increasing average age, low uptake of regular eye tests and the cumulative effects of unhealthy lifestyle choices all help to put the public at risk of sight loss. The number of people admitted to hospital for ophthalmic treatment has increased by around 30% over the past five years, driven by an increase in life expectancy and the development of new, more sensitive, detection and monitoring technologies. Ophthalmology has the second highest outpatient attendance of any medical speciality and the figure is increasing every year. Hospital departments were already struggling to cope with demand prior to the Covid-19 pandemic and it is reasonable to expect the situation will only become worse as time goes on.

Against this background, the obvious need to take preventative action to reduce poor health is established; to lessen future demand upon constrained services, to prevent avoidable and unnecessary sight loss, and to, in turn, lessen the economic burden and the social cost that would result, and therefore helping our patients to ‘age well’ and ‘live well’.

Community Patient Access

Eye care practices could make a significant contribution to this aim. They are to be found on every high street and are readily accessible to the public seven days per week, as such playing an integral role in promoting good community relations and enabling people to access eye health services with minimum disruption to their everyday lives.

A patient spends a period of time with their optometrist during which the clinician asks questions about general health, medication, family history, activities and so on and so gains a good understanding of a patient’s overall health and lifestyle. Eye care practice, therefore, clearly represents an existing resource able to influence health outcomes positively and to further reduce the long-term adverse effects of lifestyle factors that challenge an individual’s ability to lead an independent and healthy life.

It should be within our remit to talk about the links between common lifestyle factors and eye health. Here are a few obvious examples that should be familiar and which should not prove beyond the skillset or out of the remit of eye care professionals:

- Diet is important to good eye health and specific foods are beneficial for eye health. For instance, cold water oily fish, such as sardines and tuna, are excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids and there is increasing evidence for their being beneficial to cell membrane structure. Green, leafy vegetables, such as spinach and kale, are rich in the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin that are found around the macula where they have a protective effect.

- Smokers are twice as likely to lose their sight than those who have never smoked. There is an established link between smoking and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of visual loss in the UK.

- A staggering half of the UK population are classed as obese and are therefore at greater risk of developing AMD, glaucoma and, of course, type 2 diabetes. Diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy are a major cause of sight loss in the under 65s.

- Regular exercise and maintaining fitness levels are known to reduce the risk of visual impairment by over 50% from the risk associated with a sedentary lifestyle.

- Exposure to UV promotes cataract development and progression, causes ocular surface and adnexal degenerations and neoplasms, and can contribute to macular degeneration in eyes where the retina might not have any protective filter to the short wavelength radiation.

- Time spent outdoors is considered to have some protective role against the onset of myopia, with one recent study finding that children who spend an extra hour and a quarter outdoors had half the risk of developing myopia than those who did not.

Many eye care practices have the ambition to be the ‘GP of eye health’ and so good health promotion should be part and parcel of the role of the optometrist, dispensing optician and practice colleagues. With this in mind, should we perhaps mirror the GMC-stated outcome for medical graduates: ‘Newly qualified doctors must be able to apply the principles, methods and knowledge of population health and the improvement of health and sustainable healthcare to medical practice.’

This should be an aim of undergraduate optical and optometric training and, in turn, be incorporated into professional guidance. Our professional body has quite rightly raised this as a discussion point, citing the Public Health information that states the gap in life expectancy between the most and least deprived in the UK is a startling 9.3 years for men and 7.3 for women. In addition, the College of Optometrists has produced an excellent booklet entitled Lifestyle and eyes (figure 6) which serves a useful tool for introducing health messages to patients. The College have also created the ‘Look After Your Eyes’ website (https://lookafter youreyes.org) where a wealth of useful information aimed at educating patients can be found (figure 7).

Figure 6: The Lifestyle and eyes booklet helps start the conversation

Figure 6: The Lifestyle and eyes booklet helps start the conversation Figure 7: A range of useful materials is available at the lookafteryoureyes.org website

Figure 7: A range of useful materials is available at the lookafteryoureyes.org website

Planned Approach

I suggest that there might be a tiered approach to health promotion and education in terms of the level and detail at which information is pitched to best suit a patient.

Firstly, at the completion of the eye examination, the practitioner typically includes lifestyle information in their summary of what they have found and what they advise. A familiar approach would be to first summarise any presenting symptoms and history: ‘You reported not seeing as well for distance, and this is because there has been a prescription change.’

This will usually be followed by a summary of the assessed eye health: ‘Everything looks good. There are early signs of cataract in each eye, but nothing to be concerned about [with an explanation of what this means, perhaps with a diagram or image]. You have a family history of age-related macular degeneration, but again all looks within normal limits for you today regarding this.’

However, we might now add to this information by giving focused, relevant and specific lifestyle advice as appropriate to the patient, ideally matching aspects of the initial presentation with advice given at the end of an examinations. For example, if there is a family history of AMD: ‘To maintain your future eye health, are you aware that if you continue smoking, this makes it much more likely that you will develop the problems your parents had later in life. On the other hand, if you manage to quit, the risk of getting AMD will decrease from the moment you stop. I know this might be difficult, but I can let you have some information about giving up and what help is available locally for you to try if you wish.’

Initially, before gaining experience, practitioners may be wary of giving advice that may have the potential to offend. For example, addressing a patient who appears to be clinically obese. I am sure everyone will develop their own way of tackling this in a sensitive yet appropriate manner. One way may be to de-personalise he issue, and talk in general terms: ‘To make sure your eyes are as healthy as they can be, a few tips I suggest to everyone are not to smoke, look after your weight, wear sunglasses and exercise.’ Invariably the patient replies that they do not smoke, but yes, they know they should lose a few pounds and no offence is caused. This makes a follow-up statement easier to introduce: ‘Not everyone knows that the more overweight we are, the greater the chance of developing eye disease, and not just general health problems. I can give you more information about this if you are interested?’

My second tier of advice would be to widen the conversation to include issues that may be applicable to the patient’s wider network. If you know the patient has young children, a reminder to have their eyes examined along with an explanation as to why their vision needs to be checked as early as possible is an important contribution to make. For the patient with glaucoma, it is useful to ask if they have advised their brothers and sisters to get checked? If a young patient is becoming myopic, it helps to go through the evidence on what can help to slow any future progression or, if they are older and have their own children, what they might look for and do to help them.

A third tier would be to give the patient the information to take away with them, in whatever format is most useful, and to signpost other available services if appropriate. This might be a smoking cessation service, somewhere where blood tests might be undertaken, where advice about weight loss might be sought, where affordable exercise and physical activity is available, help with diet; the list is as long as it is useful. As well as materials from the College, materials produced by the Eyecare Trust are also worth knowing about and offering to a patient. With modern computer systems, that automatically generate the patient prescription, lifestyle information be added, tailored to the individual, and selected from a drop-down list and also sent in electronic form with useful links to any information decided upon as helpful. Figure 8 shows a simulated example of a patient healthy lifestyle prescription.  Figure 8: Simulated example of a lifestyle prescription for the patient to take away. An electronic version, complete with hyperlinks, might also be useful

Figure 8: Simulated example of a lifestyle prescription for the patient to take away. An electronic version, complete with hyperlinks, might also be useful

Healthy Living

Giving health advice might be taken a step further by having the practice listed as a Healthy Living Optical Practice (HLOP). This indicates the services offered by the practice, supporting prevention and offering patients healthy lifestyle advice and support, as well as developing and enhancing the job satisfaction of all practice colleagues in their promoting and supporting of healthy living and health literacy.

The Healthy Living Pharmacy initiative began in Portsmouth in 2008, and has since been extended to community optical practices in Dudley, the West Midlands and the East Midlands. Under such a scheme, practices are helped to offer the health advice service by adopting an established framework. Level 1, for example, focuses on up-skilling staff, establishing the appropriate environment and encouraging proactive health promotion, supported with good advice and signposting.

Leadership is an important element of the HLOP framework. The dispensing optician, optometrist, practice manager, or any other suitable member of staff is asked to attend HLOP leadership training, and is then responsible for creating an ethos of proactive health and wellbeing. HLOP teams have at least one full-time equivalent Health Champion, defined as somebody who has achieved the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) Level 2 qualification ‘Understanding health improvement’. The Health Champion proactively engages with patients, and the community at large, and works alongside the rest of the practice team to support people in adopting healthier lifestyles. The eye care team in an HLOP proactively and reactively engages not only with the public, but also with other healthcare professionals and commissioners. This engagement is an important feature across the whole area.

The practice environment should reflect the ethos of healthy living, and complement the promotion of health and wellbeing to the public. A hub is set up in the practice where up-to-date information about local and national health initiatives is available to the public for free, and where confidential advice and support for public health and wellbeing can be accessed. Finally, a HLOP needs to acknowledge a responsibility to contribute to a sustainable environment.

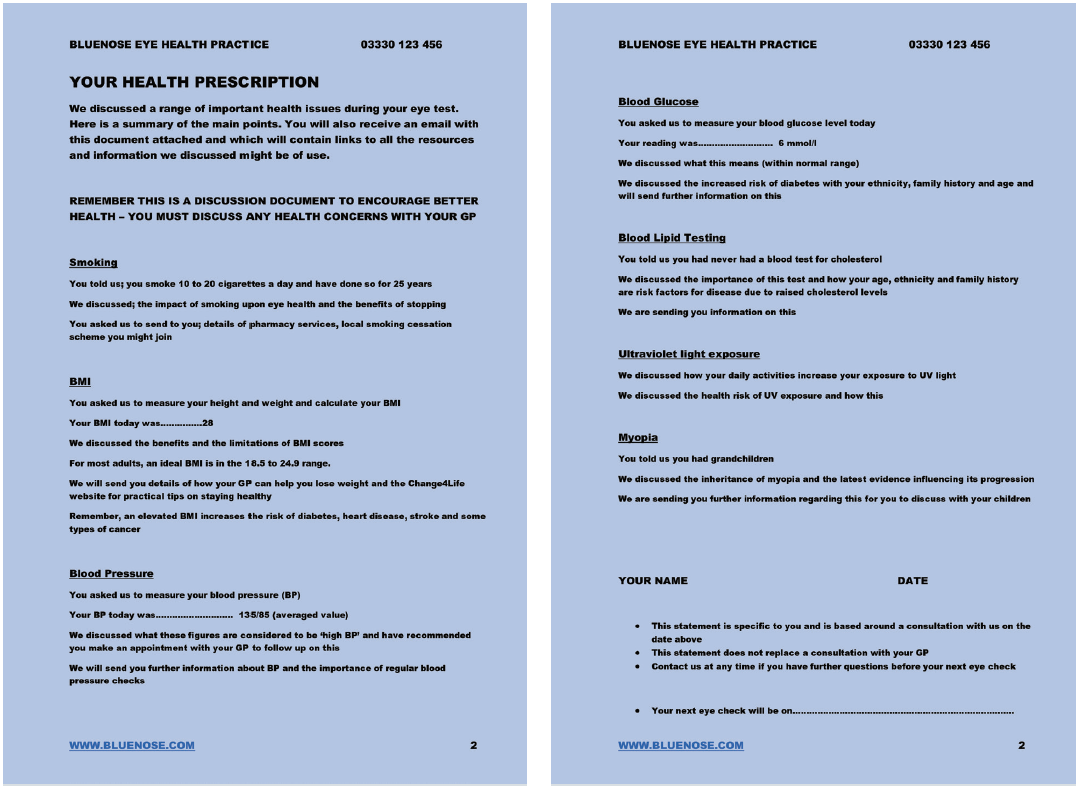

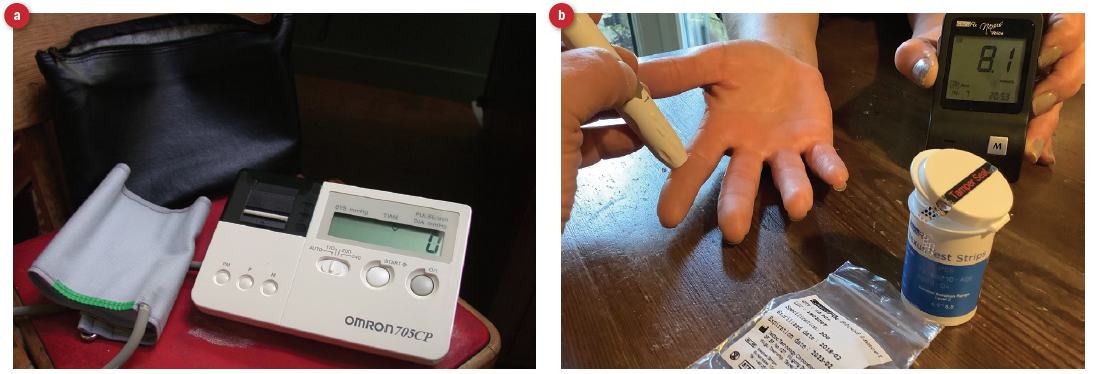

Practices meeting Level 1 requirements can be accredited as an HLOP, after which they can then work towards Level 2. This may allow them to offer dedicated, locally commissioned services, such as alcohol screening, weight management, smoking cessation and NHS health checks, including blood pressure, lipid or glucose testing (figure 9).  Figure 9: Health services at Level 2 might include (a) blood pressure testing or (b) blood glucose testing

Figure 9: Health services at Level 2 might include (a) blood pressure testing or (b) blood glucose testing

The measurement of blood pressure can be ‘added on’ as a service after undertaking the appropriate training and following prescribed protocols. Prior to the first national lockdown, a small trial in the East Midlands gave impressive results; 32% of patients needed referral for further assessment after having their blood pressure measured. The highest blood pressure recorded was 206/122 mmHg, and 4% were identified as having atrial fibrillation. It is to be hoped that, once we get back to ‘normal’, this service will be accepted as warranting funding and allowing much wider uptake by a community than self-appointment at a remote health centre.

Final Thoughts

In summary, taking a more proactive approach and giving accurate and relevant health advice will promote eye care practices to be seen as an essential part of the wider public health system. Improved relations, via better signposting and referral pathways, with other healthcare professionals and agencies will lead to increased reciprocal referrals. There is also the opportunity to positively engage with CCGs, STPs and public health departments locally, and to engage with health promotion services as an income stream in the future.

This will bring a number of benefits; increased professional satisfaction, patient trust in their practice, acknowledgement by the wider public of eye care practices as part of the primary healthcare team. And, of course, increased footfall into practices of increasingly loyal patients. •

David Cartwright is an optometrist in the East Midlands, is currently chair of the Notts/Derby Local Eye Health Network and also Chair of the charity Eyecare Trust.

Useful Resources

- Make every contact count; information about primary care usefulness in patient awareness. www.makingeverycontactcount.co.uk

- Look after your eyes; patient friendly site with downloadable resources on lifestyle influences upon eye health. https://lookafteryoureyes.org

- Live well; NHS site with excellent advice on lifestyle influences on health and up to date information about available support services and resources. www.nhs.uk/live-well

- Useful info on avoiding diabetes and cardiovascular disease in general. www.diabetes.org.uk/preventing-type-2-diabetes

- Narayan R. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration. Optician, 11.8.18

- Narayan R. E-cigarettes: a guide for eye care practitioners. Optician, 21.6.19

- Gherghel D, Ramchandani N. Obesity and ocular health. Optician, 19.4.19