Recent research has shown that, since the Covid-19 epidemic took hold, the prevalence of mental health issues has doubled, with one in five adults experiencing some sort of mental health issue during the pandemic.1 Worry, stress and anxiety were among the main causes, with women and young adults being the most impacted.2

Given that these individuals will present for eye care services at some point, it is important we are aware of our duty as eye care professionals in providing a more holistic approach to health care advice. When that patient steps into our practice, they are placing their trust in us as eye care professionals. We are well placed to spot the signs of challenges to mental well-being, to identify potential ocular manifestations and to be able to assist in recommending and advising upon appropriate care and support services. This article explores how we can easily adopt our best practice approach in order to achieve these aims as effectively as possible.

What is well-being?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines well-being as being ‘happy, comfortable or healthy’.3 This may be further broken down into four categories of well-being as follows:

- Emotional

- Physical

- Social

- Workplace

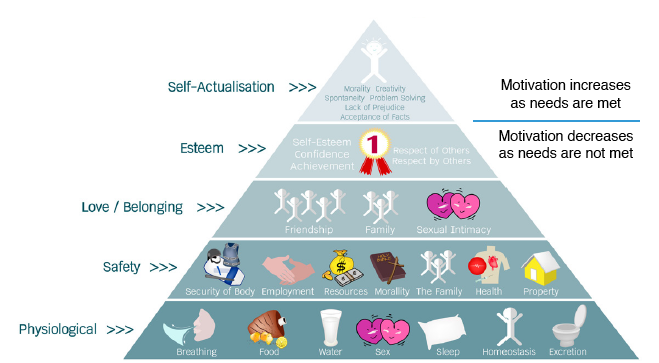

Maslow’s theory (as summarised diagrammatically in figure 1) suggests basic needs must be satisfied before higher level physiological needs if we are to achieve self-fulfilment and ‘happiness’.4

Figure 1: Maslow’s theory of needs

Figure 1: Maslow’s theory of needs

How has the pandemic affected well-being?

The pandemic has resulted in unprecedented levels of disruptions to many aspects of life, resulting in many personal and lifestyle changes.5 These changes in daily routines, such as taking on and juggling new responsibilities (for example, home schooling), balancing working from home with home life, developing the new skills required in the new technological communications world, and facing up to future uncertainty, may all have contributed to increased stress levels. Finding the right family-work life balance, looking at ways to stay connected with friends and family and ensuring future security can be overwhelming; especially for those who are experiencing the negative financial consequences of furlough schemes or job loss.

A major consequence of the lockdown has been reduced social interaction, with time apart from loved ones. Not surprisingly, increased levels of loneliness are widely reported. Many self-shielding elderly people, who have had minimal human contact, are struggling with their isolation and are almost certain to be feeling low, lonely and anxious. For some, a visit to the optician will be their first outing in a while and this could add to what might already be considered to be a daunting experience.

Spotting the signs initially

Identifying signs of compromised well-being starts even before the patient enters the consulting room. Careful awareness and observation of appearance, body language, posture, and generally the way somebody presents themselves is useful and is something all staff members should be comfortable in undertaking. This may give vital clues as to how somebody may be feeling. Consider, for example, the following when identifying anxiety:

- Is the patient avoiding eye contact?

- Is the patient’s head hung low?

- Is the patient walking slowly or nervously?

- Is the patient fidgeting with their hands, or sweating unduly?

Communication is key

How many times have you gone to a restaurant or retailer where someone has, in your opinion, treated you with excellent customer care? What did they do? How did they make you feel? Now, consider a time when you had a bad experience. Again, how did that make you feel?

The key thing that everyone wants is to be listened to and understood. Researchers have found that a single, quick glance of a person’s face (just 33 to 100ms) is sufficient for the viewer to form an initial impression of that person.6 This is worth remembering as patients will quickly form an opinion of you as their eye care professional (ECP), perhaps picking up on your mood, making a judgement of your confidence, professionalism or authority. To make a positive impression from the start, always greet the patient by their name and welcome them into your consulting room with a smile. Staff and practice appearance all contribute to this initial impression; under current conditions, this might reinforce trust by obvious adherence to current guidance on cleanliness and sterility, while still maintaining friendliness and approachability.

Does COVID-19 consultation guidance support this?

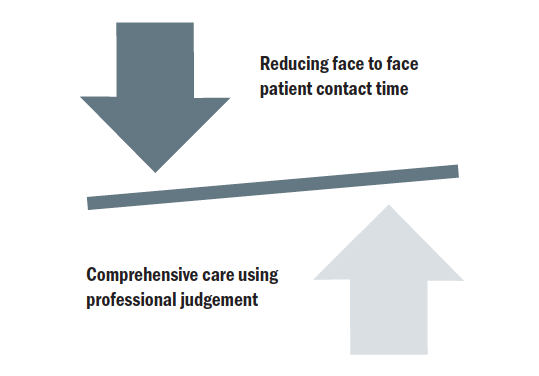

Best practice guidance to minimise the risk of transmission promotes reducing face to face contact time with patients and avoiding unnecessary conversations.7 To ensure comprehensive care is provided, increased professional judgement should be applied (figure 2). It is essential to get this balance right as appropriate to each individual patient.

Figure 2: Balancing safety and clinical care

Figure 2: Balancing safety and clinical care

To overcome any concern of increasing consultation time, a useful way of ensuring adequate questioning about health and well-being is to use appropriate questionnaires or thorough pre-appointment triaging/screening teleconsultation calls.

One simple effective question (‘how are you today?’ or ‘how’s your day been?’) followed by good listening and empathy with the individual is often all that is needed. This can offer vital clues that certain red flags relating to mental health may be present and help drive focus for the following eye examination. If these are then confirmed as relating to ocular health and refractive signs, then appropriate advice, such as reference to support websites or resources, may be all that is necessary.

History taking – identifying risk factors

As you find out the main reason for a patient’s visit, it is always important to ask about general health and medication. Any changes in either of these since their last appointment may be reflected in low emotional or physical health. This is a perfect opportunity to ask how the patient has been keeping ‘during these times’. Their wellbeing might be gauged by a simple ‘how are you feeling?’ It is also important to tailor the questions to each patient, perhaps establishing whether they have been able to get out much, are struggling with anything, or whether they have family or other support nearby?

Have they been in contact with many other people? This is a useful question and might easily be introduced later in the history-taking, for example when asking about occupation. If a patient is still working, asking them how they have found it and are they managing okay is helpful. If they have lost their job, then asking them how they have been coping and are feeling about it, and have they got any support is also helpful.

The role of the ECP

ECPs are usually not trained therapists, and each of us should appreciate the scope of our skill and experience,8 avoiding diagnosis, management and treatment for conditions beyond our ability. That said, ECPs are health care practitioners and so are well placed to spot signs and symptoms and should be able to signpost to the appropriate care. Sometimes, all that is needed is simply to take a couple of minutes to listen. This may be the first time a patient has been able to explain to an independent professional about what they are going through and feeling.

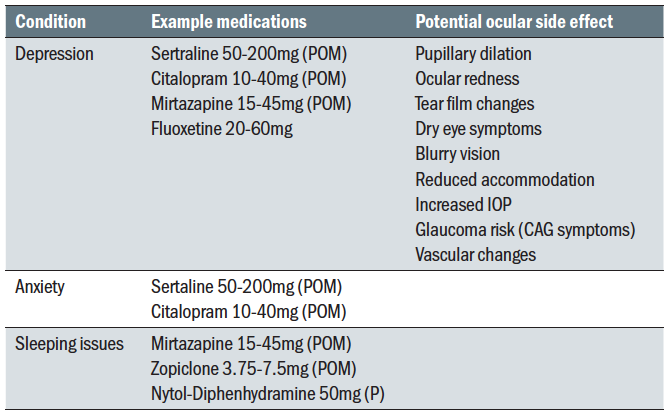

Importantly, most emotional issues influence physical health issues. Such systemic health issues (heart problems, stroke, diabetes, high blood pressure, raised cholesterol to name a few) can lead to eye problems. Also, many medications used to manage depression and anxiety have been associated with ocular changes, such as tear film disruption, mydriasis, accommodative insufficiency, and increased intraocular pressure and glaucoma risk.9 This latter impact is especially important to identify in those found to have narrow anterior chamber angles. The ocular effects of some commonly prescribed drugs for mental health management are outlined in table 1.10

Table 1: Ocular adverse effects of some medications used for mental health

Table 1: Ocular adverse effects of some medications used for mental health

The ECP role should be concerned with prevention before cure. We can gently advise our patients that, when people experience stress and anxiety, this can lead to problems with general and eye health. This can be a useful way to introduce ideas for a healthier mindset and lifestyle. This might include specific advice, such as relating to diet and exercise, or the recommendation of relevant resources or contact details for support groups. Examples of such useful contacts include the following:

- MIND (mind.org.uk)

- Young Minds (youngminds.org.uk)

- Samaritans (116 123 or www.samaritans.org)

- SHOUT (free text support 85258)

- Age UK (ageuk.org.uk)

- NHS website (nhs.uk)

Specific advice, helpful when given confidently and based on evidence, might address healthier eating, reducing alcohol intake, improving water intake, maintaining appropriate exercise levels, connecting better with friends, family or those with similar interests or concerns, or even the taking up of a new hobby. You are not telling them what to do but rather, having listened to their story, you are offering ideas and resources that they may pick up upon and ultimately benefit from.

Using phrases like ‘I understand’ or ‘I know someone in a similar situation’ will usually help the patient to feel they are being understood, that they are not alone in their circumstance or situation. They will also then be more open in taking up some of the suggestions.

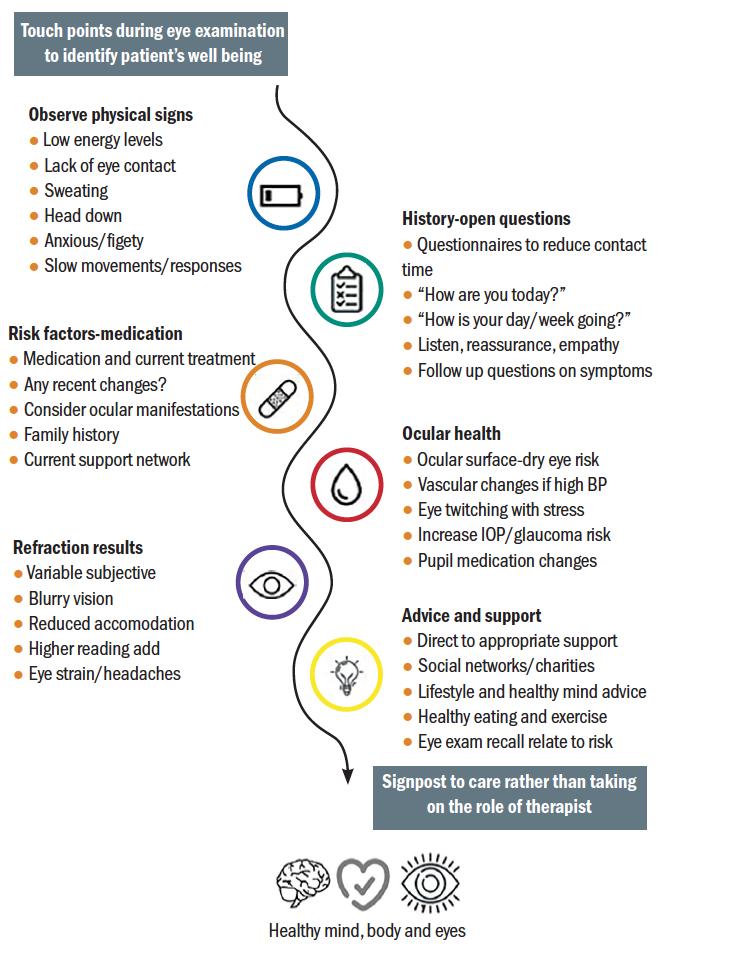

Opportunities for identifying issues related to wellbeing and for discussion of options to address these exist at various stages of the eye examination. These are summarised in figure 3.

Figure 3: Touch points during a routine eye examination for consideration of mental wellbeing.

Figure 3: Touch points during a routine eye examination for consideration of mental wellbeing.

Building a rapport

Throughout any consultation, building a rapport with the patient is essential. Things to support this include:

- Talk directly to the patient

- Maintain appropriate eye contact

- Actively listen

- Use patient-friendly language and avoid jargon or alarmist

terminology - Use mirroring tactics; for example, if the patient is using a lot of hand movements to communicate, try to do the same. If they use certain words repeatedly, then use those same words back. Give encouragement throughout the consultation – but obviously avoid any implication of mimicry or mockery.

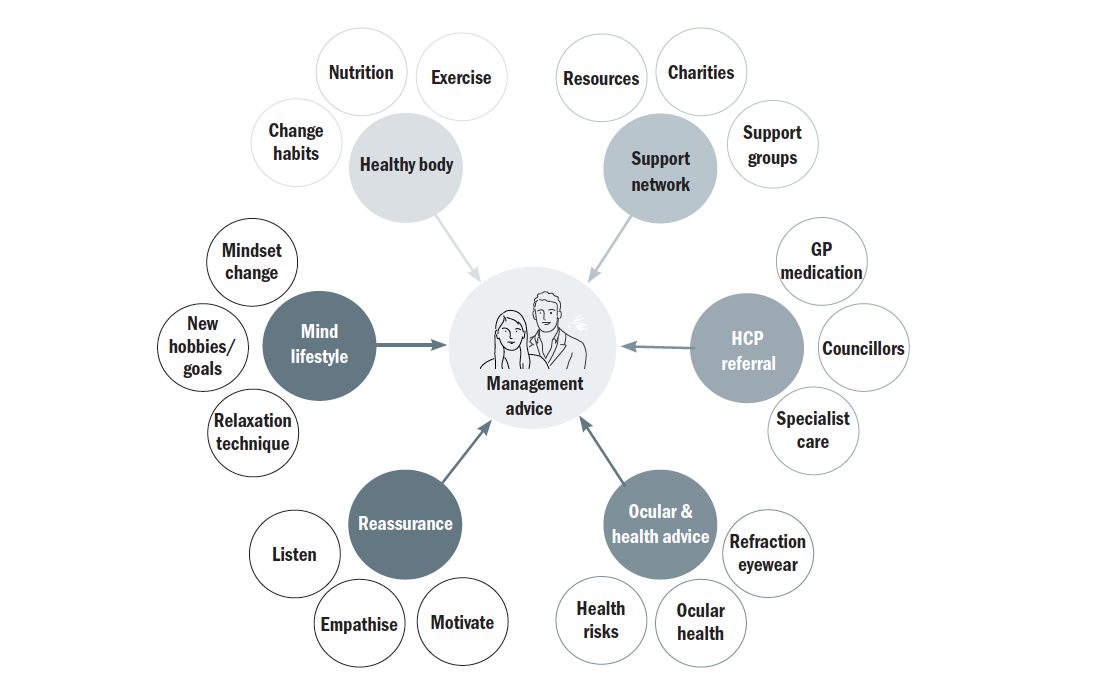

The mind and body are intricate and complicated yet interlinked. Each can impact on the other. As ECPs, we cannot treat mental health conditions directly, but we can support with suitable recommendations, resources and options. See figure 4 for an overview of management strategies.

Figure 4: Management options for health and well being

Figure 4: Management options for health and well being

Detecting the hidden

Some individuals may be embarrassed or self-conscious about their mental health state. However, with careful and sensible interaction, a patient might be encouraged into being more open about their state of mind. A lot can be obtained from careful, constructive questioning and lead to a recommendation to seek additional care, investigation, or support. The generic question ‘how are you today?’ is relevant in any eye service consultation; from spectacle collection to contact lens appointment through to low vision assessment and enhanced services. Telephone consultation will focus on using strong listening and questioning skills, whereas video consultations also give opportunity for body language observation.

Case scenarios

Let us now consider three cases where the intervention of an ECP made a difference.

Case 1

A young mum presents for an eye examination and a constant avoidance and lack of eye contact suggests she is withdrawn and lacks confidence. She mentions she is struggling with her work/life balance and greatly misses socialising since having the baby. She admits to being constantly stressed and tired, and feels a ‘lack of support’. She spoke to a pharmacist about sleeping problems and has since has been taking a Nytol tablet most evenings; with mixed success. She is experiencing sporadic headaches, but has no visual or ocular signs upon examination.

Management: The priority here is to listen, give encouragement, lifestyle recommendations and general support.

Outcome: Her mood appears elevated after being able to discuss her problems in a safe, independent environment. She leaves feeling more positive. At a follow up contact lens appointment a few weeks later, she thanks you and has now managed to make time for exercise and better nutrition and is sleeping well with out the sleeping medication.

Suggested well-being resource and support:

- Mind; general mental health support

- Helpline: 0300 1233393

- Website: www.mind.org.uk

- Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM); may be able to offer her support with the stress of balancing home life

- Helpline: 0800 585858

- Website: www.thecalmzone.net

- No Panic; specifically, for people who suffer panic attacks (need to gauge usefulness here)

- Website: www.nopanic.org.uk

Case 2

A vulnerable 80-year-old diabetic man mentions during his eye examination how he is feeling quite alone and isolated at present. He no longer goes out (today is a first for a long time) and has minimal contact with his family. His vision is reduced, and you notice dry eye and background diabetic retinopathy.

Management: After discussing local support and resources available relating to his emotional state, this is an opportunity to discuss nutrition, the importance of stability for diabetes control, some general points about eye health and retinal screening, and dry eye management.

Outcome: He leaves feeling more self-confident and even looks forward to doing some ‘extra healthy’ food shopping. He also plans to contact some of the support networks available

Suggested well-being resource and support:

- Silverline; telephone network for like-minded elderly of similar experience, interests and intellect

- Helpline: 0800 708090

- Website: www.thesilverline.org.uk

- Age UK

- Helpline: 0800 6781602

- Website: www.ageuk.org.uk

- Diabetes UK

- Helpline: 0345 1232399

- Website: www.diabetes.org.uk

Case 3

Remote video eye consultation with a young male patient who has never been on any medications previously. When asked about medication today, you notice he looks a bit nervous and embarrassed and seems evasive.

Management: You gently prompt the patient that medication can impact on the eyes, but reassure him that whatever is discussed remains confidential. He instantly relaxes and opens up regarding recently having been prescribed anti-depressants. This was prompted by him recently having lost his job.

Outcome: This now presents an excellent opportunity to ask about how they are now feeling, whether they currently have any further support, and to ask if they would like any.

Suggested well-being resource and support:

- Mind; general mental health support

- Helpline: 0300 1233393

- Website: www.mind.org.uk

- Men’s Health Forum; a chat support service through text or email that offers advice from experts on mental health for young men

- Website: www.menshealthforum.org.uk

- Papyrus; this is a service concerned with suicide prevention so unlikely discussed without ECP having relevant experience in this area

- Phone: 0800 0684141

- Website: www.papyrus-uk.org

Conclusion

Initially it may seem easier to avoid the extra questions on well-being and not ‘open a can of worms’, but if you can change your mindset to seeing it as providing an essential service for the best interest of the patient you may become more open to it. If there is a chance and opportunity to support and be the difference in a patient’s life why would you not take it? With all new things it can seem a bit daunting but by embracing this as your new routine, you may find your role as an eye care professional becomes even more rewarding.

Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience of working with in education, industry, and both practice and head office roles. He currently works for Menicon and the College of Optometrists. He has been involved with various organisations across the sector and is currently part of the GOC Education Committee, President Elect of the BCLA and a Past Chair of the British and Irish University and College Contact Lens Educators. He has been awarded fellowships from the BCLA and IACLE.

Sheena Shah is an Optometrist working in practice currently at Vision Express. She is also an author, rapid transformation therapy practitioner, life coach, mindfulness, meditation, NLP practitioner, and nutritionist, working with individuals, families, businesses and schools under her well-being company Inspiring Success.

References

- www.ons.gov.uk Accessed 06.12.20

- www.mentalhealth.org.uk Accessed 06.12.20

- Oxford English Dictionary 3rd edition: Oxford University Press, 2010

- Maslow, AH. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96.

- WHO (2020) Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak Paper available at; www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1 Accessed 06.12.20

- South Palomares JK, Young AW. Facial First Impressions of Partner Preference Traits: Trustworthiness, Status, and Attractiveness. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2018;9(8):990-1000.

- High-level-principles-for-remote-prescribing_.pdf (www.optical.org) Accessed 06.12.20

- General Optical Council (2016) Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. Available at; www.optical.org. Accessed 06.12.20

- Gherghel D (2020) Ocular side effects of system drugs3-Central nervous system agents. Optician 22 May 2020; 18-22

- Richa S, Yazbek JC. Ocular adverse effects of common psychotropic agents. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(6):501-26.