‘Nystagmus is an eye movement disorder characterised by abnormal involuntary rhythmic oscillations of one or both eyes, initiated by a slow phase.’

The condition is relatively common within the UK population, affecting approximately one to two per 1,000 children and adults.1,24 Nystagmus is most commonly encountered in the hospital paediatric ophthalmology and adult strabismus clinics. In community primary eye care settings, however, nystagmus is seen less frequently, when patients either present with recent onset nystagmus or have been discharged from the Hospital Eye Service (HES).

There are many underlying causes of nystagmus, not all of which will be addressed in this article. Infantile nystagmus rarely occurs as an isolated condition (idiopathic), but more commonly is part of a ‘multisystem disorder’ associated with profound visual impairment or a neurological condition.2

The variation of presenting visual impairment is wide, largely dependent upon associated pathology. Visual acuity can be near normal in a few and in others, can be profoundly poor.

Every presentation is unique, each case presenting a challenge to optometrists, opticians and contact lens practitioners.

Despite this, there are traits that most will display. An understanding of these can be used to the clinician’s advantage in providing the best examination experience, refractive outcome and advice on the best type of corrective appliance.

This article aims to expand upon the Nystagmus Network ‘Training the professionals’ series of webinars from May 2020; primarily looking at the little details and adaptations to routine clinical examination that might make all the difference in cases of known infantile nystagmus.

Background

While the priority of treatment for a new presentation of nystagmus is always via urgent hospital referral to determine the underlying cause, in cases of known infantile nystagmus (IN), previously known as congenital nystagmus,3 the next step is to attempt to improve the visual outcome and visual function as far as is possible.

The hospital outpatient setting is often the only eye care experience that new IN attendees to your practice may have known pre-discharge. Patients and their parents and carers may feel apprehensive about coming to a community optometrist for ongoing care. They may believe that optometrists do not understand nystagmus. They may be wary, having been told that the nystagmus is not curable, that nothing can be done, and that they may be sold spectacles that they just do not need. Being able to reassure patients that you understand the challenges they face, the condition they live with and possess the relevant skills and knowledge to assess them will go a long way to building trust and a good clinical relationship. So where do we begin?

The Optometrist – Patient Journey

Appointment booking

Your ‘front of house’ staff will be used to asking questions about ‘reasons for visit’ and any known underlying visual needs or access requirements at the time of appointment booking. It is important that the timing is one where the patient is relaxed and refreshed, where the oscillation/nystagmus may be more manageable.4 Allocating a suitable duration for the examination will allow for the possibility of slower visual responses and appropriate recovery time. Patients with such complex visual needs perform better when not under time pressure or when they are fatigued.5 Allowing for this by making ‘reasonable adjustments’ will be of benefit to all involved.

Pre-screening

Pre-screening is not appropriate for a patient with nystagmus. Visual fields and tonometry require special consideration and should be performed by those experienced with nystagmus patients. As these tests are often stressful and visually fatiguing for the patient, consider performing visual fields after refraction or on a separate day. Similarly, to avoid photostress, fundus imaging with a high intensity flash should be the last thing you do and not the first. Autorefractors are inappropriate for an oscillating eye and their results more than likely will be less accurate than a carefully managed objective and subjective refraction.6

Building trust and rapport

A deep and comprehensive history is essential. The limitations on quality of life may not be quite what is anticipated for patients with such variable vision. Some patients with nystagmus are really worried about their ‘wobbly eyes’ and not being able to make eye contact. For others, it is their frustration with poor clarity or fluctuating vision. Some do not feel their nystagmus affects them at all. Finding out about their daily routines, hobbies, working conditions and the impact that they feel their nystagmus has, will inform the eye professional, build rapport, trust, empathy and provide the best care possible (figure 1). A quality of life (QoL) questionnaire is a useful tool to gauge how much a patient is affected by their condition. The Pilling, Thompson and Gottlob research on social and visual function in nystagmus suggests a strong correlation between the condition and social confidence.7

Figure 1: Developing a rapport is essential (image courtesy of Nystagmus Network)

Figure 1: Developing a rapport is essential (image courtesy of Nystagmus Network)

It is not unusual for a parent to ask whether it is ‘normal’ for their child to be experiencing some of the following symptoms:

- Tired or achy eyes

- Variable vision

- Poor spatial awareness

- Shyness

- Eye rubbing

- Head shaking/nodding

- Poor eye contact

- Irritability when tired

- Confusion in crowds

Parents may report a delay in some motor milestones or reluctance of a child to walk unassisted at the same age as peers or siblings. Family history is important. There is often a genetic component and there may be other members of the family who have nystagmus or traits of associated conditions such as night blindness, pale skin or poor vision.

Difficulty with making eye contact is normal with many nystagmus patients and should not be considered a barrier during the consultation. Be aware that clarity in all verbal communication is essential as subtle non-verbal interactions will be too nuanced, making the experience more difficult for the patient.

Patients with established IN, rarely experience oscillopsia despite having a constantly moving retinal image.8,9 Head nodding is sometimes a feature; however, the head movement is often in a different direction and phase to the oscillopsia, and considered independent of it.10

For patients with acquired nystagmus, the presenting symptom is often constant oscillopsia and requires urgent ophthalmological investigation.

For patients without a history of nystagmus who present with new intermittent oscillopsia and also associated changes of posture or orientation, underlying vestibular involvement should be suspected. A GP referral for further advice is advisable.

Visual Function Assessment

Assessing vision

As for many patients with visual impairment, your assessment of visual function will begin from the moment you first call them into the consulting room.

Watching how they navigate themselves towards you, around obstacles and into the test chair will give you valuable clues. Do they need assistance? Do they move confidently? Are they bothered by the bright lights of the consulting room? Do they orientate themselves in a new environment easily or do they need assistance? Do they have an abnormal head posture or unusual gait? Make a note of any initial observations.

One of the predominant features that underpins everyday optometric practice is the use of Snellen acuity charts. High contrast and with unequal numbers of letters per line contribute to a less than satisfactory assessment of vision for patients with complex visual needs. There has been a move latterly to using EDTRS/Bailey Lovie LogMAR charts, especially in hospital and low vision clinics. However, in practice the Snellen chart is often still ‘king’. Despite this, high contrast acuity tests do not give an accurate assessment of visual function. Self et al reported recently that ‘visual acuity is not a global measure of visual function.’1 This is a core lesson when dealing with a patient with any complex visual needs.

With patients affected by nystagmus, a more holistic assessment of vision is useful, including LogMAR or Snellen acuity charts and age-appropriate tests. Routine use of a Pelli Robson chart to assess contrast sensitivity function is also a good idea.

‘Slowness to see’ is thought to be a product of saccadic fluctuation when attempting foveation or re-foveation and is not thought to be associated with latency in visual processing.11 This slowness to see is thought to impact both acuity and contrast and is worth recording.

Where the nystagmus is associated with retinal dystrophy or ocular albinism (notably the most common types of ocular co-morbidity associated with IN), glare is a common complaint. Helping the patient to combat glare will in turn improve contrast and help overall visual function.

Where the nystagmus is secondary to a physical, neurological or developmental delay or disability, practitioners should be aware that communication with the patient may be different. Use of Landolt C, tumbling E, matching symbols, vanishing optotypes (Cardiff cards), Lea’s symbols or Teller Preferential Looking cards (at 50cm) may be of benefit in assessing acuity. Where there is a high degree of ametropia and complexity of needs, it is vital the patient is given the best opportunity possible to interact visually with their environment.

Binocular vision assessment

Careful binocular vision assessment is essential. Between 16-52% of nystagmus patients will have strabismus, although the expression of this is variable. Idiopathic IN is the least likely to present with strabismus, and the incidence increases with ocular albinism, and congenital retinal dystrophies, increasing further with bilateral malformations of the optic tract (eg optic nerve hypoplasia).5

Breaking the BV assessment down into distinct components, allowing recovery time between each is sensible. Incorporating stereoacuity testing, convergence, motility and cover test into the routine may have to be performed in a different order depending on the type of visual impairment and aetiology that you are faced with.

For example with a photosensitive patient, measuring stereopsis, convergence, accommodation and cover testing might need to precede motility. Pen torch brightness may cause a slower visual recovery time, light/dark adaptation issues and stress the visual system.

Full motility in all directions of gaze, taking note of the corneal reflexes also in the primary position is important. The oscillations may change in speed and intensity with differing directions of gaze and must be noted. This will help to guide you to the null point, which the patient will often naturally adopt for concentrated tasks. At this null position, the frequency of oscillations is ‘dampened’ and so this tends to be the point at which best visual function occurs.

Cover test and alternating cover test (figure 2), with and without abnormal head movement (AHP), will allow you to unearth any latent nystagmus component, and prism bars should be used to estimate the angle of deviation. However, it can be tricky with the larger or more pendular non-jerk type oscillations; but worth building confidence by taking the time to assess strabismus where possible.

Figure 2: Binocular assessment of a nystagmus patient (image courtesy of Nystagmus Network)

Figure 2: Binocular assessment of a nystagmus patient (image courtesy of Nystagmus Network)

A frosted cover stick is a more reliable choice than an occluded cover stick as it gives fewer misleading results. Full occlusion during the examination can increase the amplitude of the oscillation in the uncovered eye. If the patient is struggling with fixation, using Hirschberg reflexes is acceptable.

It is useful to note that a majority of the oscillations are horizontal,12 with or without a rotary component. Oscillations which change to vertical movements on up and down gaze or become non-conjugate are more suspicious of a neurological aetiology. Pendular nystagmus is often associated with an identifiable visual system pathology13and poorer visual function.

Convergence needs to be measured with the near refractive correction in place, with AHP which is adopted for null point. Not only should the optometrist look at the ease of convergence, but they should note any changes in amplitude or frequency of nystagmus.

Near cover test should be performed with the near refraction in place, both with and without AHP.

It is more common for near acuities to be better than expected and convergence seems to play a role in this.21,22 Some patients have a different null position for distance and near. These positions for the near null point and distance null point become very important when dispensing spectacles and visual aids. Where there is associated macula pathology or hypotrophy, however, this improved near vision function may not occur.

Lack of binocularity and resultant lack of depth perception is very common in this group of patients. Visually impaired patients, (especially those with pronounced nystagmus), often experience heightened stress levels in busy and crowded places. Some of this may be due to their ‘slowness to see’ alongside compromised depth perception. Increased stress levels are known to impact negatively upon visual function in nystagmus, and so many will avoid putting themselves in situations which may cause stress.14

Static retinoscopy

Since autorefraction for nystagmus is unreliable, going back to your traditional well-honed static retinoscopy technique is

essential.

Around 73% of patients will have a null zone within 10° of the primary position.12 However, phoropters should be avoided with nystagmus, even if the null point is central.15 Use of a trial frame is preferable, as the fit can be adjusted/modified to enable the patient to adopt any abnormal head posture to engage their null point. Fogging the fellow eye in preference to occlusion will avoid amplifying the nystagmus.

Whether you prefer streak or spot retinoscopy, the challenge is in interpreting the red reflex on a mobile eye. It is best practice to perform static retinoscopy in the dark and with the patient viewing a target at their null point where the amplitude of their oscillation will be minimal. Working ‘on axis’ with the patient engaging their null point position is key; concentrating on the centre of the red reflex and ignoring peripheral scissoring/swirling caused by aberrations.

Reassurance and accuracy are vital with children, working closer than 2/3m if necessary. Children with IN are usually discharged from the HES when they have stabilised refractive error or once the critical period of visual development is considered complete, (between ages seven and 13 years on average). They will be used to cycloplegia.

Even if you are used to unusual retinoscopy reflexes from lens opacities or corneal ectasias, it is important with nystagmus to be especially efficient with retinoscopy using slow sweeps of the ret beam. Be mindful to reduce the intensity of the retinoscope beam and exposure time to minimise their discomfort. A ret-rack is a handy addition to make spherical lens bracketing quick. Large pupils, iris transillumination and aniridia will make the patient unusually photosensitive.

Although it is acknowledged that with the rule astigmatism is most common,16 it must not be assumed. Many patients with IN and other ocular comorbidities may have experienced poor emmetropisation leading to high levels of irregular or oblique astigmatism.

Subjective refraction

An optometrist experienced with retinoscopy will not need to spend long on subjective refraction. However, as with all complex and low vision patients, the ‘just noticeable difference’ of a ±0.25 sphere or cyl is not going to be appropriate, especially on a moving eye.

Binocular refraction can be more reliable in nystagmus patients, especially when there is a good level of acuity. As for retinoscopy, use the patients’ null zone and also consider the benefit of full aperture lenses, especially if the null zone is eccentric beyond 10°.

Pinhole acuity will be almost impossible to achieve.

Consider the target size used for subjective responses. While a line of letters will tell us about visual performance, in terms of seeking a reliable response from the patient, it might be useful to direct them to only one letter on the smallest resolvable line of letters to remove confusion. The ‘re-foveation’ phase will cause a ‘slowness to see’ and the optometrist will need to allow for this. Although a reduction in acuity may be due to a combination of meridional amblyopia17 and retinal pathology, allowing time for re-foveation is crucial.

Verhoff rings are 6/12 size and duochrome targets are designed to be sensitive to +/-0.25 sphere. In the unlikely event that each eye is monocularly corrected to 6/7.5+, this confirmation test might be considered redundant for this group of patients.

Jackson Cross-cylinder using an appropriately sized ring-shaped target and a higher-powered cross-cylinder will be remarkably accurate. Having a +/-1.00 D cross-cylinder as part of your routine armoury is essential for low vision patients. Cross-cyl technique may require moderating to increase the exposure time before twirling the cross-cyl. Consistency is key.

At times improving acuity even after a detailed subjective refraction can be challenging, but rechecking with retinoscopy over the final result is helpful, especially if the subjective endpoint is no’t clear. Monocular acuities are nearly always worse than binocular acuity.18

If a reduced single character on the chart is used as the subjective target, remember to record acuity in the usual way, with a full chart, allowing crowding to come into play.

Post-refractive contrast sensitivity function is a useful benchmark of improvement if subjective improvement in high contrast letters is not immediately appreciable.

Record-keeping should include details of monocular and binocular acuities with the final result, whether the null point was used for this and the back-vertex distance.

Presbyopia and near correction

As previously mentioned, the convergent null point can often give a surprisingly good level of vision.19 However, you will need to measure the optimal viewing distance for the patient at which this occurs.

It would be wrong to assume that a young patient with nystagmus may have normal anticipated levels of accommodation. Amplitudes are often low or poorly maintained in patients with ocular albinism25 and Down’s syndrome26 for example.

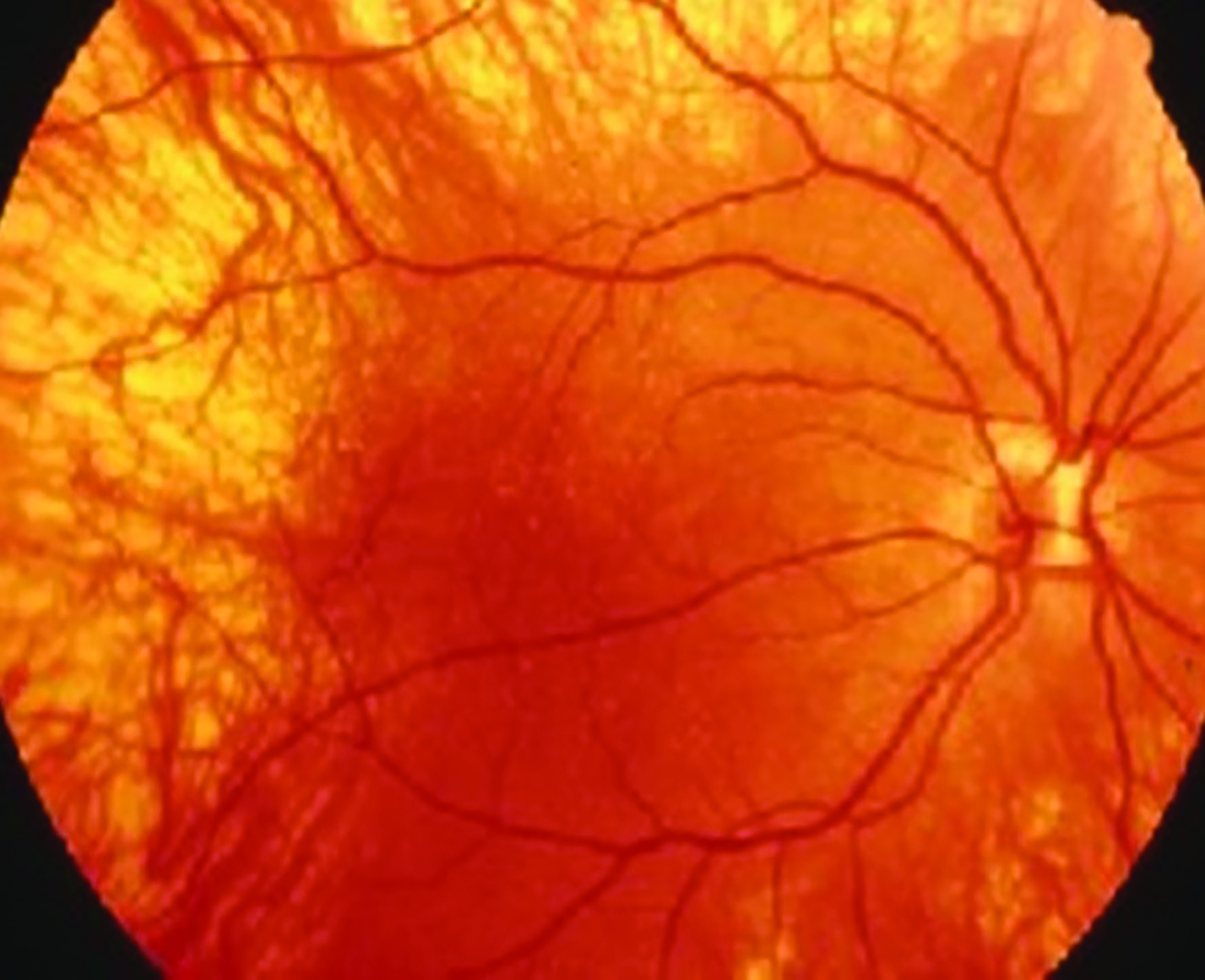

Figure 3: Albino fundus

Figure 3: Albino fundus

Consider the smallest resolvable print size at the preferred working distance and work with this as your guide for a magnifying aid or a near add for comfort.

The patient will almost certainly have developed adaptive techniques20 going through school or at work, where they use a reading stand or set their computer screen at their preferred distance. There is an outside chance that they have not considered this before – and if they do, it is advisable to ask them to check how far away their screen/stand is from their face. Correcting to this distance is key to prescribing the best corrective appliance for that patient.

Most patients will have learned to enlarge the font size on

digital devices and improve contrast where possible to achieve near-normal rates of reading. Studies suggest that in cases of IN, horizontal reading speeds are better than vertical reading speeds for those who read vertical texts.18

With presbyopia, the reduced accommodative/ convergence drive may cause base IN prism to be required to help maintain comfortable convergence. This is particularly true if they are binocular. However, if the null point is only monocular then prismatic assistance will not be necessary. Use of prisms in younger patients, to stimulate convergence may require base OUT prisms to induce better control and is something that experienced practitioners may trial.21

Sometimes the ‘near add’ may be higher than expected for the age, especially in early presbyopia.

Ocular Examination

Fundus examination

Depending upon associated ocular comorbidities, there are certain characteristic traits to recognise. Those with ocular albinism will have low levels of RPE pigmentation and foveal hypoplasia; the choroidal view will be visible through the translucent retina. There may be coloboma, optic nerve hypoplasia, very small optic cups, unusual fundus pigmentation, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). It is good practice, to record the fundus image photographically so that sequential clinical visits can be closely compared while screening for changes to the retina and associated structures. Good quality non-mydriatic fundus cameras are much more commonplace in high street practice.

Slit-lamp examination

Often a very small amplitude nystagmus is much more noticeable on slit-lamp examination. It is entirely possible to achieve a normal level of slit lamp detail using indirect and direct illumination techniques.

With albinism, iris transillumination and pale irides are seen clinically. They can also have structural anterior chamber abnormalities. Gonioscopy would of course not be easy on an oscillating eye, but it is useful to know that the anterior structures may not be ‘the anticipated norm’.

Nystagmus patients may have coloboma, aniridia, congenital cataract and other structural anterior segment irregularities. Some children may be aphakic following congenital cataract extraction in the first few weeks or early years and be wearing high plus, soft contact lenses for aphakia.

Fields and pressures

Non-contact tonometry with the patient using the null point (if possible) will be the safest way to estimate the ocular pressure.21 Goldmann and Perkins applanation methods are likely to increase the risk of abrasions on a mobile eye. Handheld devices such as ‘Tonopen’ and ‘iCare’ rebound tonometers may also be acceptable to a skilled user. Recordings are likely to be an estimate on a mobile eye and repeat readings may be difficult to achieve. With aniridia, albinism and coloboma, structural anterior angle anomalies make glaucoma more of a risk.

Visual fields will be difficult due to many parameters. If the patient’s nystagmus worsens with occlusion, then a frosted occluder may be used. Threshold single stimulus strategies will give variable reliability given the instability of fixation; suprathreshold single stimulus strategies will be more reliable.

Kinetic perimetry may be more repeatable with tried and tested historical techniques, such as a detailed confrontation

test or with a Bjerrum screen. Amsler testing might be a

consideration for the central macula field if the patient is capable of resolving the grid lines with their near correction in place. Goldman kinetic perimetry is still performed in most hospital eye departments although, monitoring of visual fields for suspect glaucoma may not be reliable with manual kinetic methods. There are new visual field tests emerging on the market which require fixation change on a computer/tablet screen, and these may prove to be more reliable in the future for low vision patients.

Dispensing considerations

Refractive disorders are more common in patients with infantile nystagmus than in the general population and accurate refraction is the best way to improve visual function.23 Ensuring that the optical appliance dispensed will fit the occupational and lifestyle needs takes some skill. Dispensing the carefully obtained refractive result in to an optimal pair of spectacles is vital to performance of the appliance.

Nystagmus patients often have higher levels of ametropia and there may be associated facial characteristics which affect frame fit and choice. The frame must fit well before any measurements are taken. With the types of refractive error often seen in such complex bilateral ocular conditions, attention to lens thickness, weight, and tinting options is an especially important consideration.

Where the patient may be very light sensitive, think carefully about whether a photochromic option will work quickly enough for them. They may be better with two pairs of glasses of different transmittance. High contrast specialist tints should be discussed, especially where there are ocular comorbidities such as retinal dystrophies.

If the patient is binocular and uses a null point close to primary gaze, interpupillary distance should be measured at that null position, marked on the dummy lenses and then rechecked on the patient having fitted the frame correctly. Pupillometers are an acceptable way of measuring PD for these patients, as is measurement of ‘canthus to canthus’.

The use of contact lenses in nystagmus will be discussed in further articles, however, they do often provide better acuity for driving and of course enable the patient to use plano wrap sunglasses if they are very photosensitive.

Referral

Working within one’s professional experience and recognising our own expertise and scope of clinical competence is central to best practice in optometry. Any amount of reading will not replace experience and practitioners are reminded that if there is any doubt in whether the patient needs a referral or a second opinion then it should be sought. Young patients especially should be reassured that the referral route back to see their ophthalmologist is a straightforward process.

There are several ‘red flags’ which require urgent referral to ophthalmology:

- If the patient is a child and presenting with nystagmus for the first time, then referral is essential as there is no way of being certain that this is IN without a positive history from a young age. Children can develop acquired nystagmus and IN is more commonly diagnosed a few weeks after birth or in the first six months. Therefore, a new presentation in an eight-year-old should be considered as suspicious.

- Oscillopsia is rarely a symptom of longstanding stable infantile nystagmus. Constant oscillopsia should trigger an urgent referral.

- Late onset nystagmus in an adult is highly suspicious of acquired nystagmus secondary to trauma, pharmacological reactions or a neurological condition.

- Torsional nystagmus in the absence of retinal pathology and if the patient is also symptomatic of feeling unwell.

Routine referral may be necessary for a longstanding nystagmus patient who is developing new visual symptoms of more commonplace eye conditions. They may also wish to seek an opinion for pharmacological treatment of their nystagmus, genetic testing or counselling or be considered for Certification of Visual Impairment (CVI).

Figure 4: Support groups offer educational resources (image courtesy of Nystagmus Network)

Figure 4: Support groups offer educational resources (image courtesy of Nystagmus Network)

Nystagmus patients are not always offered a CVI by their ophthalmology department or may initially be reluctant to consider it. Children, however, may require a CVI when they have significant difficulties with their sight to enable them to have access to a Qualified Teacher for Visual Impaired (QTVI), which might not otherwise be available to them. It will also support the school in accessing additional classroom support. Discussing CVI is always sensible if you feel it is appropriate.

When it comes to driving, common sense has to prevail. With a good binocular visual field and acuities that satisfy the DVLA requirements, there should be no barrier to obtaining a provisional driving licence for a nystagmus patient. However, borderline acuities, which may worsen under stressful situations, makes the decision less clear-cut. Contact lenses might improve the acuities significantly compared to spectacles for driving. Should a CVI be in place, the patient may need to de-register in order to apply for a provisional licence.

Support groups

The following support groups are just some of those which are available to patients and their families. They play a very important role in the sight loss community, providing educational resources, kinship, counselling, information, reassurance and support.

- Nystagmus Network (nystagmusnetwork.org)

- RNIB (rnib.org.uk)

- Albinism Fellowship (albinism.org.uk)

- Retina UK (retinauk.org.uk)

- Deaf Blind (deafblind.org.uk)

- Down’s Syndrome Association (downs-syndrome.org.uk)

- Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy Society (lhonsociety.org)

Sarah Arnold is an independent optometrist from Hampshire who contributes to the education programme of the Nystagmus Network.

For comprehensive information and resources, go to; https://nystagmusnetwork.org

References

- JE Self, MJ Dunn, T Erichsen, I Gottlob, HJ Griffiths, C Harris, H Lee, J Owen, J Sanders, F Shawkat, M Theodorou, J P Whittle, Nystagmus UK Eye research group (NUKE). Management of nystagmus in children: a review of the literature and current practice in UK specialist services, Eye 34, 1515–1534 (2020)

- Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The neurology of eye movements. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006

- Avallone JM, Bedell HE, Birch EE, et al. A classification of eye movement abnormalities and strabismus. 2001;2010 (November 18, 2010): Report of a National Eye Institute Sponsored Works. Available from http://www.nei.nih.gov/news/statements/cemas.pdf

- Bifulco, P., Cesarelli, M., Loffredo, L. et al. Eye movement baseline oscillation and variability of eye position during foveation in congenital nystagmus. Doc Ophthalmol 107, 131–136 (2003)

- Abadi RV, Dickinson CM. Waveform characteristics in congenital nystagmus. Doc Ophthalmol. 1986;64(2):153–167

- K Camille DiMiceli, MD, Brooklyn, NY Albinism: What You Can do for Your Patients: Young patients with oculocutaneous albinism can benefit from traditional ophthalmological care and new low-vision devices. Review of Ophthalmology, [Published 11 Nov 2014]

- RF Pilling, JR Thompson, I Gottlob, Social and Visual function in nystagmus, Br. Journal of Ophthalmol 2005; 89;1278-1289

- Bedell HE. Perception of a clear and stable visual world with congenital nystagmus. Optom Vis Sci. 2000;77(11):573–581

- Lee AG, Brazis PW. Localizing forms of nystagmus: symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6(5):414–420

- Abadi RV, Bjerre A. Motor and sensory characteristics of infantile nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(10):1152–1160

- Matt J Dunn, Tom H Margrain, J Margaret Woodhouse, Jonathan T Erichsen; Visual Processing in Infantile Nystagmus Is Not Slow. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015;56(9):5094-5101

- Abadi RV, Bjerre A. Motor and sensory characteristics of infantile nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(10):1152–1160

- Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The Neurology of Eye Movements. 5th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015

- Cham KM, Anderson AJ, Abel LA. Task-induced stress and motivation decrease foveation-period durations in infantile nystagmus syndrome. Investig. Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(7):2977–2984

- Wilkinson ME OD, Shahid KS. OD, MPH. Going old school: A refresher on retinoscopy; Refracting without an autorefractor or a phoropter has its advantages for some patients. Brush up on your skills with these case examples. [published 15 May 2017 Review of OptometryZahidi AA, Woodhouse JM, Erichsen JT, Dunn MJ. Infantile nystagmus: an optometrist’s perspective. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2017;9:123-131

- Wang J, Wyatt LM, Felius J, et al. Onset and progression of with-the rule astigmatism in children with infantile nystagmus syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(1):594–601

- Bedell HE, Loshin DS. Interrelations between measures of visual acuity and parameters of eye movement in congenital nystagmus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32(2):416–421

- Liat Gantz, Muli Sousou,Valerie Gavrilov, Harold E Bedell, Reading speed of patients with infantile nystagmus for text in different orientations Vision Research, Volume 155, February 2019, Pages 17-23

- Abadi RV, Bjerre A. Motor and sensory characteristics of infantile nystagmus. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(10):1152–1160

- Debbie Wiggins, J Margaret Woodhouse, Tom H. Margrain, Christopher M Harris, and Jonathan T Erichsen Infantile Nystagmus Adapts to Visual Demand Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007 May;48(5):2089-94

- Matt J Dunn; Debbie Wiggins; J Margaret Woodhouse; Tom H Margrain; Christopher M Harris; Jonathan T Erichsen. Eye Movements, Strabismus, Amblyopia and Neuro-ophthalmology, The Effect of Gaze Angle on Visual Acuity in Infantile Nystagmus Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science January 2017, Vol.58, 642-650.

- Zahidi AA, Woodhouse JM, Erichsen JT, Dunn MJ. Infantile nystagmus: an optometrist’s perspective. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2017;9:123-131. Published 2017 Sep 25. doi:10.2147/OPTO.S126214

- Hertel RW. Examination and refractive management of patients with nystagmus. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000;45:215-220

- Sarvananthan N, Surendran M, Roberts EO, et al. The prevalence of nystagmus: The Leicestershire Nystagmus Survey. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(11):5201–5206

- Karlén E, Milestad L, Pansell T. Accommodation and near visual function in children with albinism. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019 Sep;97(6):608-615. doi: 10.1111/aos.14040. Epub 2019 Jan 31

- J Margaret Woodhouse; Accommodation in Down syndrome - more questions than answers. Journal of Vision 2010;10(15):34