The first article in this series (Optician 19.02.2021) established that the age group showing the greatest increase in the use of information technology and internet access in recent years was the over 60s; exactly the age group most likely to suffer some form of visual impairment. It then clarified the terminology in current use (assistive technology versus adaptive technology) before looking at desktop and laptop computers and the ways their software platforms are easily adapted to assist with viewing. In this article, I will consider tablets and smartphones with particular focus on features they all have that eye care professionals should know about when helping their patients. These assistive features are common throughout modern devices, without the need to download specialist or dedicated apps or software, something I will cover in part three of the series.

Smartphones and Tablets

The main difference between smartphones or tablets and desktops/laptops is portability. Even then, the distinction is somewhat blurred with some newer laptops having touchscreen facility and detachable screens that can then be used as a freely portable tablet-style unit separate to their keyboard, peripherals and physical memory drive.

The only real difference between a tablet and a smartphone is size; a tablet is a larger smartphone and a smartphone is a smaller tablet. All should include:

- Communication software; telephone, messaging, text-based, internet, video-sharing

- Ability to use apps; it is worth noting that issues of presentation sometimes means that some apps are only available for either tablet or phone, though this is less common these days

- A camera; an integrated light is almost universal on smartphones, less common with tablets.

- Full online accessibility

- Location and orientation sensing

- Voice/sound capabilities

So, perhaps a better description of smartphones and tablets might be ‘fully portable electronic communication and information processing devices’ – not sure this will catch on. The advantage of thinking of them as variations of the same device, however, means when you are in a position to recommend such a device to a patient, the main consideration is which is going to be more important for this person; portability or screen size? For use on the move, smartphones will be best. For text and image enhancements, the larger field offered by a bigger screen makes the tablet the better choice. Almost all of my patients have smartphones, while fewer have a tablet. Sometimes, the frustration in using their smartphone, such as when texting and email (even after the viewing enhancements described in this article), is addressed by them acquiring a tablet. The price of tablets has dropped greatly in the last couple of years, and there is no doubt the larger screens make for easier text and image viewing.

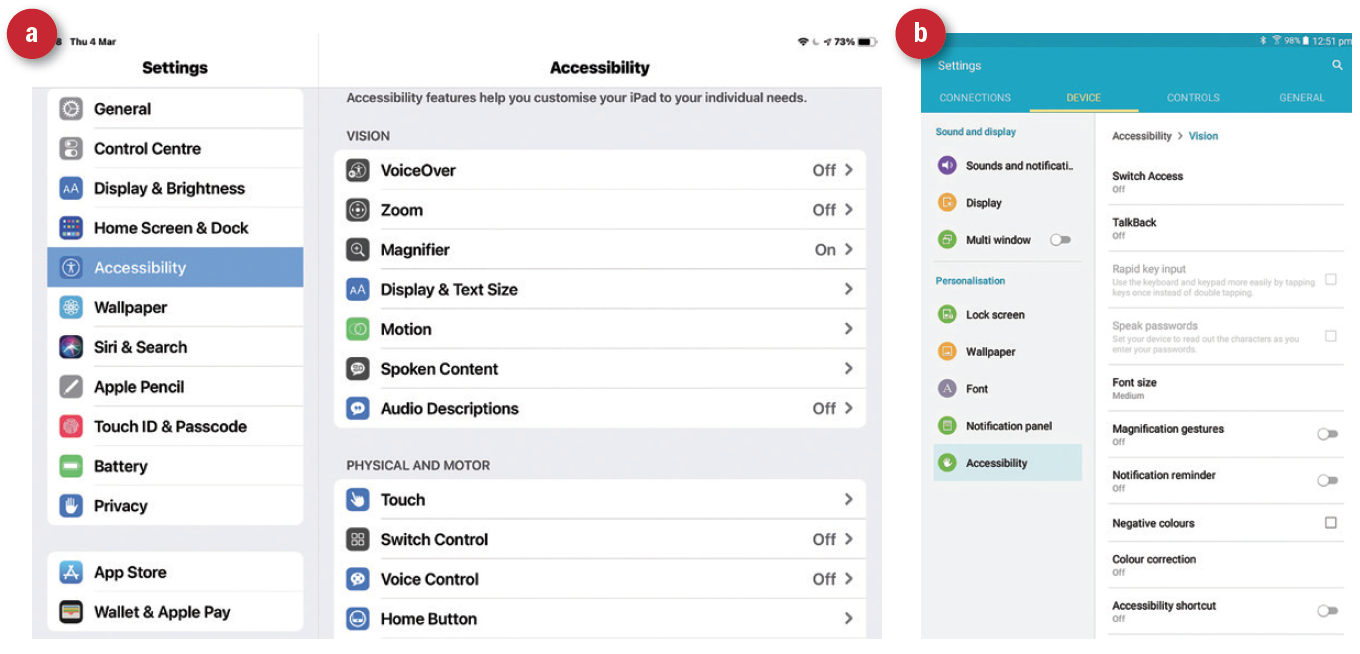

Apple devices (iPads and iPhones) use the iOS software platform, while most other devices use the system called Android which was developed by Google (figure 1). The main exception here is devices running Windows (from Microsoft). Some tablets run Windows and can be thought of as a touchscreen laptop, so can be adapted using the ‘Ease of Access’ process described in part one in this series. Microsoft no longer produce Windows smartphones, instead having thrown in their lot with Android.

Figure 1: Android tablet and smartphone (left) and Apple iPad and iPhone (right)

Figure 1: Android tablet and smartphone (left) and Apple iPad and iPhone (right)

It is a safe bet that, if the device is not an Apple product, it is likely to use the Android operating system. Does this matter? Well, the answer has to be ‘rarely’. Some apps are exclusively for Android, others for iOS, but this is rarely a concern. Also, the accessibility options for each platform will differ in style and sometimes capability, though the inter-system rivalry usually means any new development in one is soon matched by similar

in the other.

A Note about Confidentiality

Just as an eye care professional should be able to offer useful advice about lighting and magnification, they should also be able to explain at least the basics in setting up a portable device to optimise its use for people with a visual challenge. In the author’s experience, many a patient who admits to the ECP that they have been struggling with their device, may then pull it out of their bag and ask the ECP to either explain how they can adjust the settings or even ask them to make the adjustment there and then.

It is important, therefore, to always remember that electronic devices will carry a vast amount of information, much of which is likely to be highly personal or sensitive and viewing by a third party might compromise the patient’s security. Every

intervention needs to be very clearly explained from the start, full informed consent given by the patient, and accurate records of what has been done made. Unless permission is explicitly granted, confirmed and recorded, then the safer approach is usually to offer suitably printed and explained guidance for the patient or someone close to them to use to make changes

themselves.

Software Platform Adaptation

It is useful if you have access to an Android and an Apple device. This way, every time there is a software update, you can check to see if the accessibility options have changed or been added to. This happens a lot, and in the last couple of years some

improvements have been included that can make a major difference for someone with a visual impairment. The various options available to assist viewing are to be found within the ‘Settings’ area, the link to which is invariably found on the home screen. As a minimum, based on the most common requests from my patients, I would suggest it is worth knowing at the very least how to change the text to help with messaging and email.

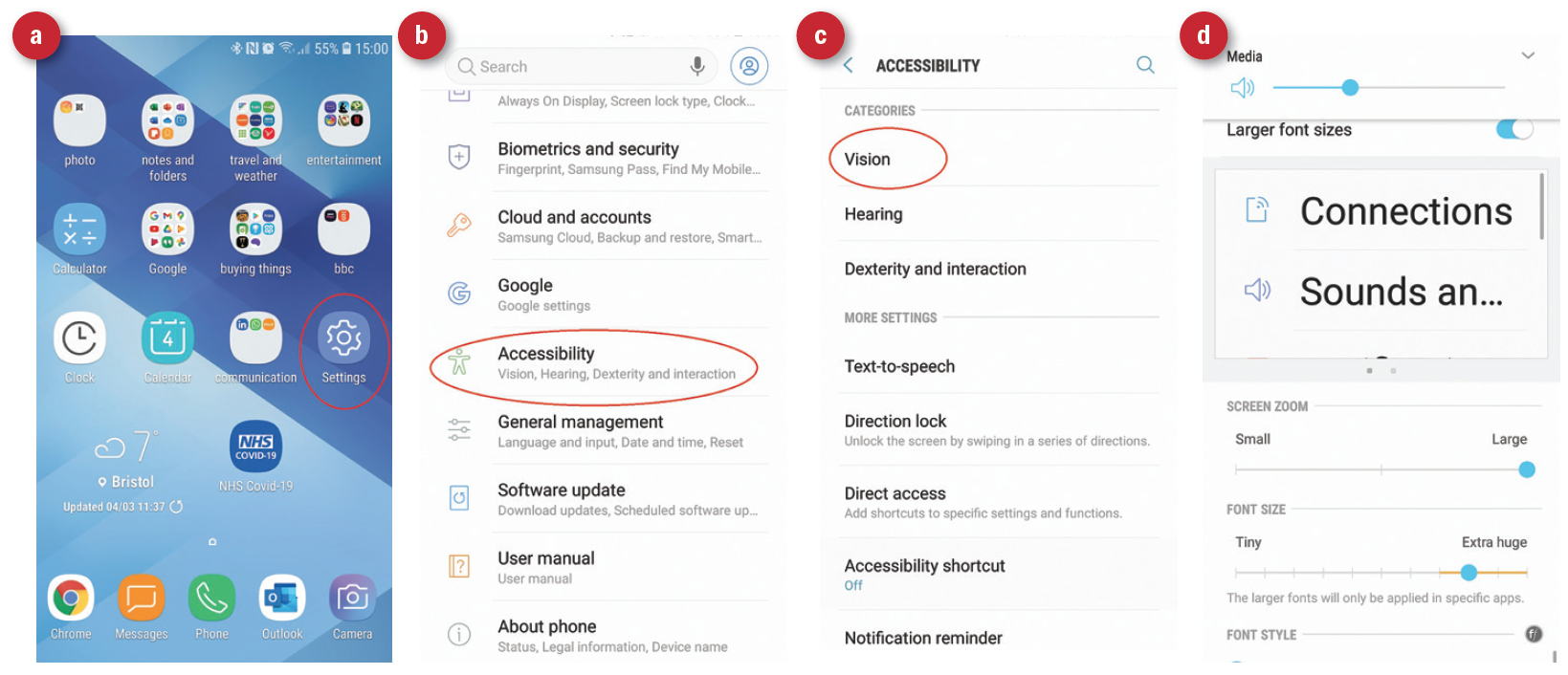

For an Android smartphone, first locate the ‘settings’ button and (figure 2a) and click. Then select ‘accessibility (figure 2b), then the ‘vision’ option (figure 2c). It is here that you find a whole range of ways of changing the screen view, including increasing the contrast and the size of text fonts (figure 2d). This will change the view of any software running within the operating platform, including the text and email.

Figure 2: Adapting an Android device; (a) select the Settings tab on the home page, (b) Accessibility, (c) Vision, (d) the options you want

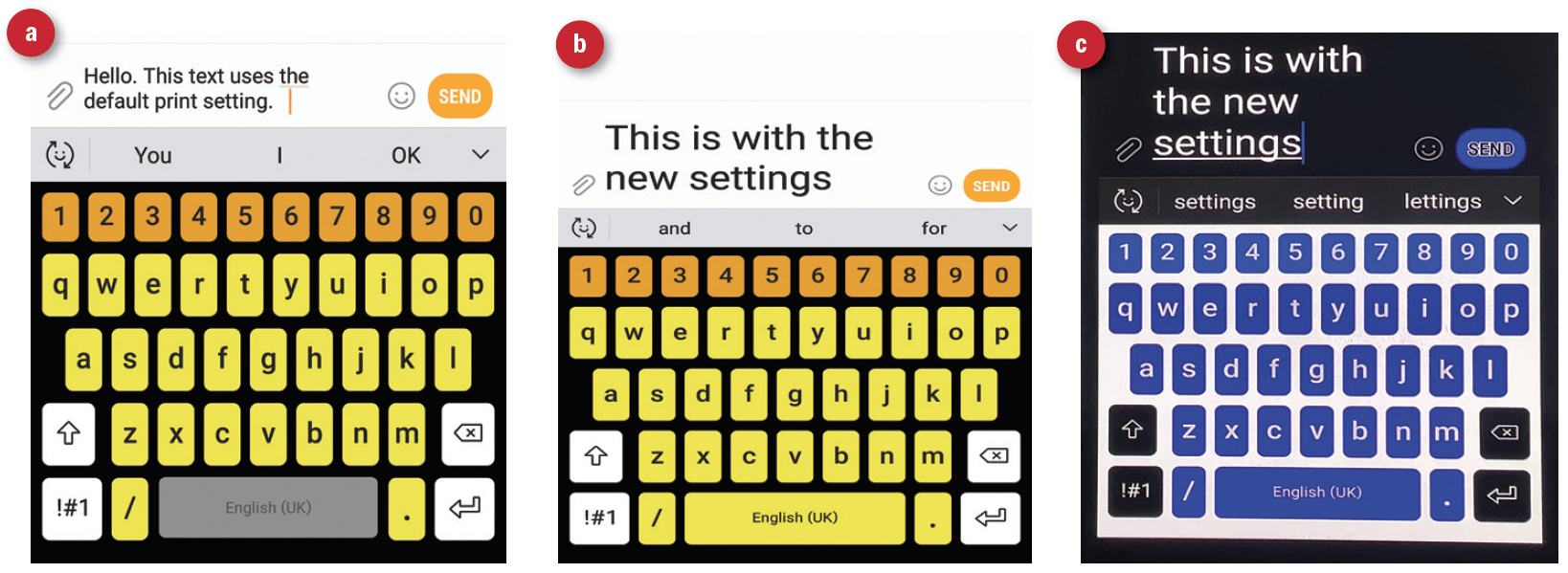

For a patient struggling with texting using their Android smartphone, I first select the ‘high contrast keyboard’ option (figure 3a). I then increase the font size (figure 3b) and, finally, consider using the reverse contrast setting (figure 3c). Importantly, always involve the patient in the process as their preference may not tally with your predictions of their requirement. For example, a patient may prefer a more challenging smaller font (perhaps combined with the ‘magnifier’ cursor option) if the increased field means that screen orientation is easier for them.

Figure 3: Enhance texting by (a) setting a high contrast keyboard, (b) increasing font size, (c) using reverse contrast

Figure 3: Enhance texting by (a) setting a high contrast keyboard, (b) increasing font size, (c) using reverse contrast

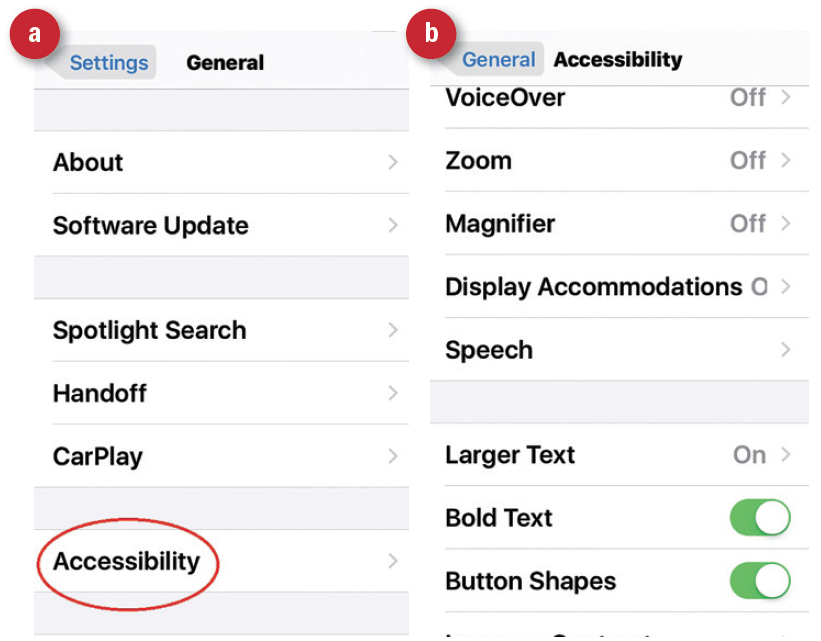

For an iPhone, follow the Settings > General > Accessibility route (figure 4a) and you will see the Apple range of adaptations (figure 4b). The process will be similar for an Apple tablet (figure 5a) or an Android tablet (figure 5b), albeit with some variation in the layout or appearance depending on the actual device.

Figure 4: Changing display on an iPhone; (a) select Accessibility

Figure 4: Changing display on an iPhone; (a) select Accessibility

in options (b) select from the various options

Figure 5: Changing the display on (a) an iPad and (b) an Android tablet

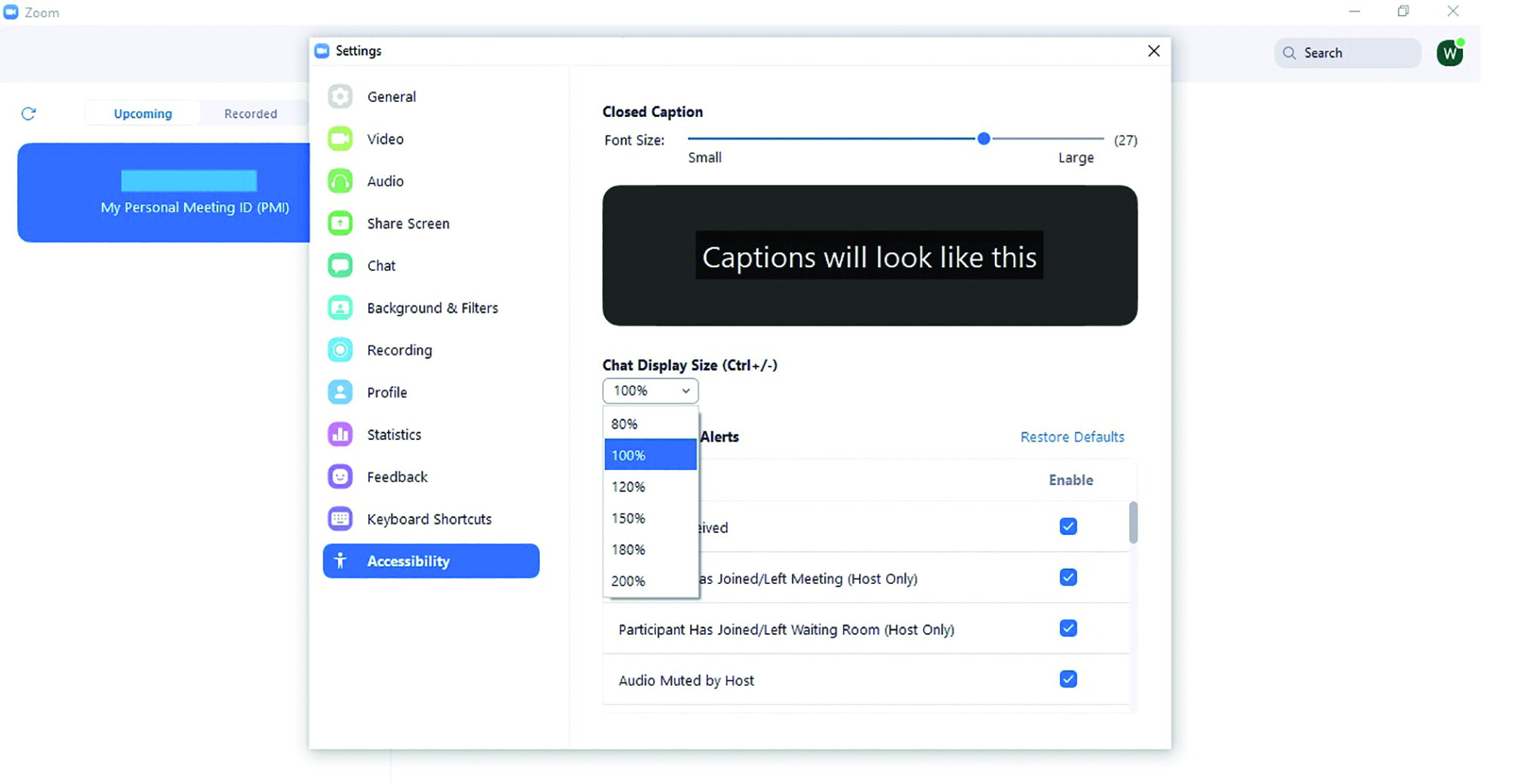

Remember, the changes are not necessarily going to be applied for websites being viewed. To help here, the best option is to use one of the free add-on downloads available within most search engines (such as those available for Chrome users described in part one of this series). The most commonly used downloaded programs, such as Zoom, should have their own accessibility settings options (figure 6).

Figure 6 :Changing the appearance of Zoom

Cameras

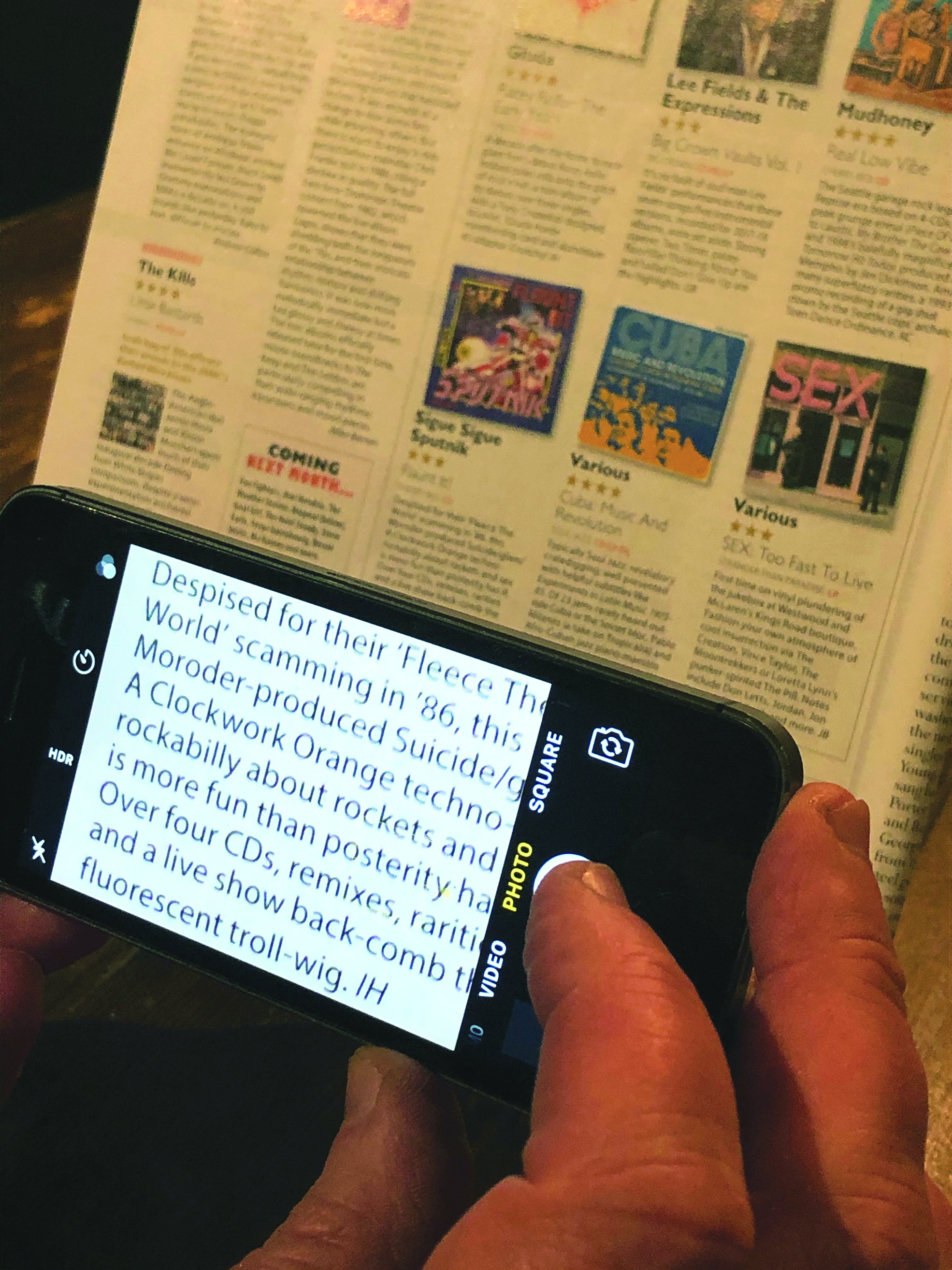

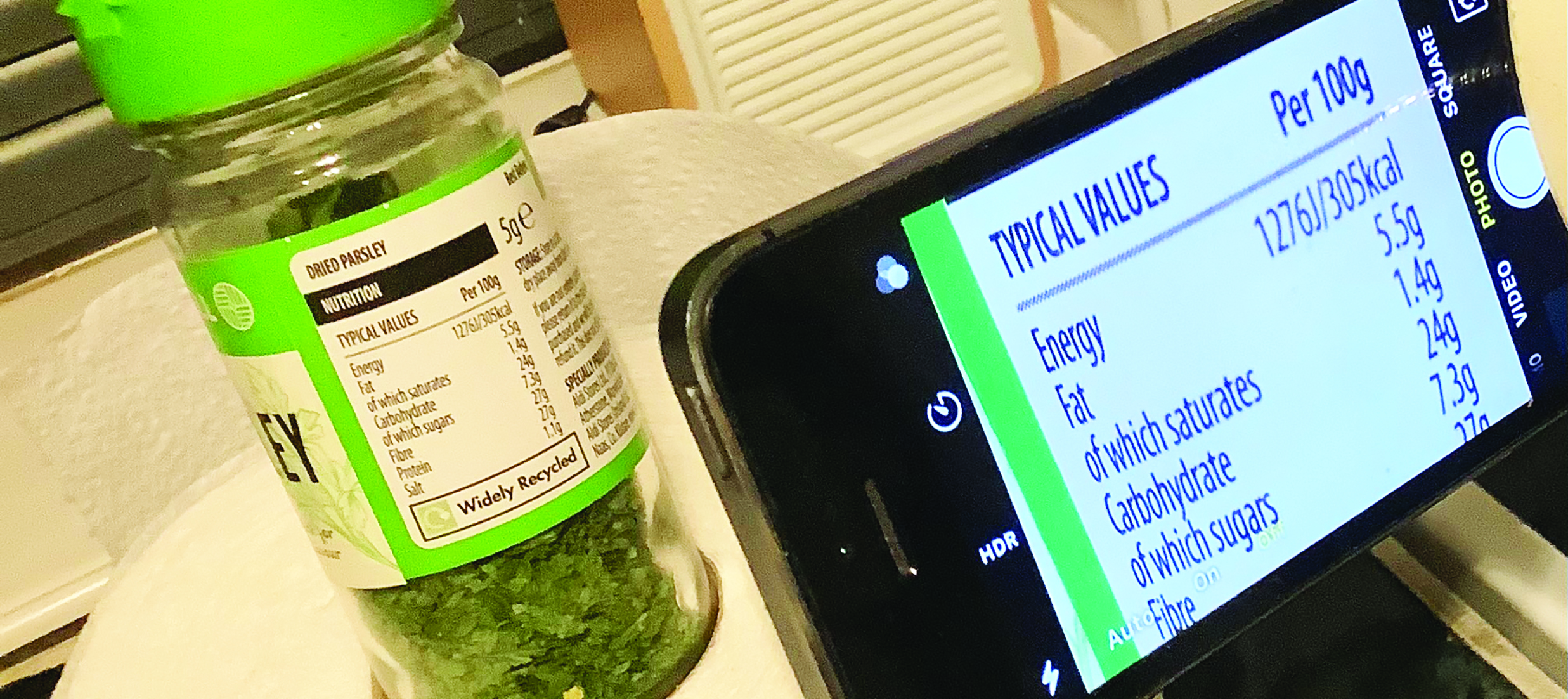

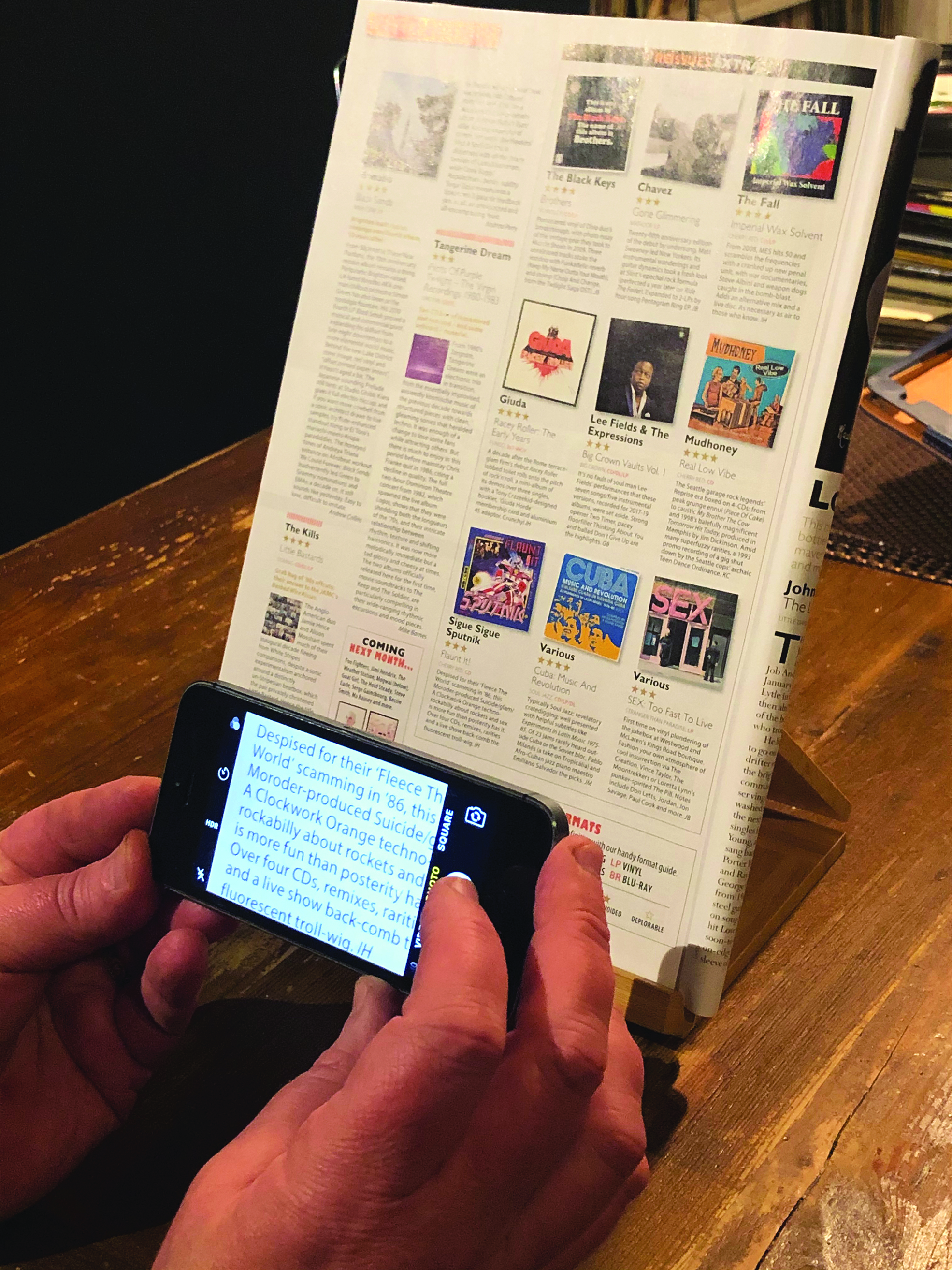

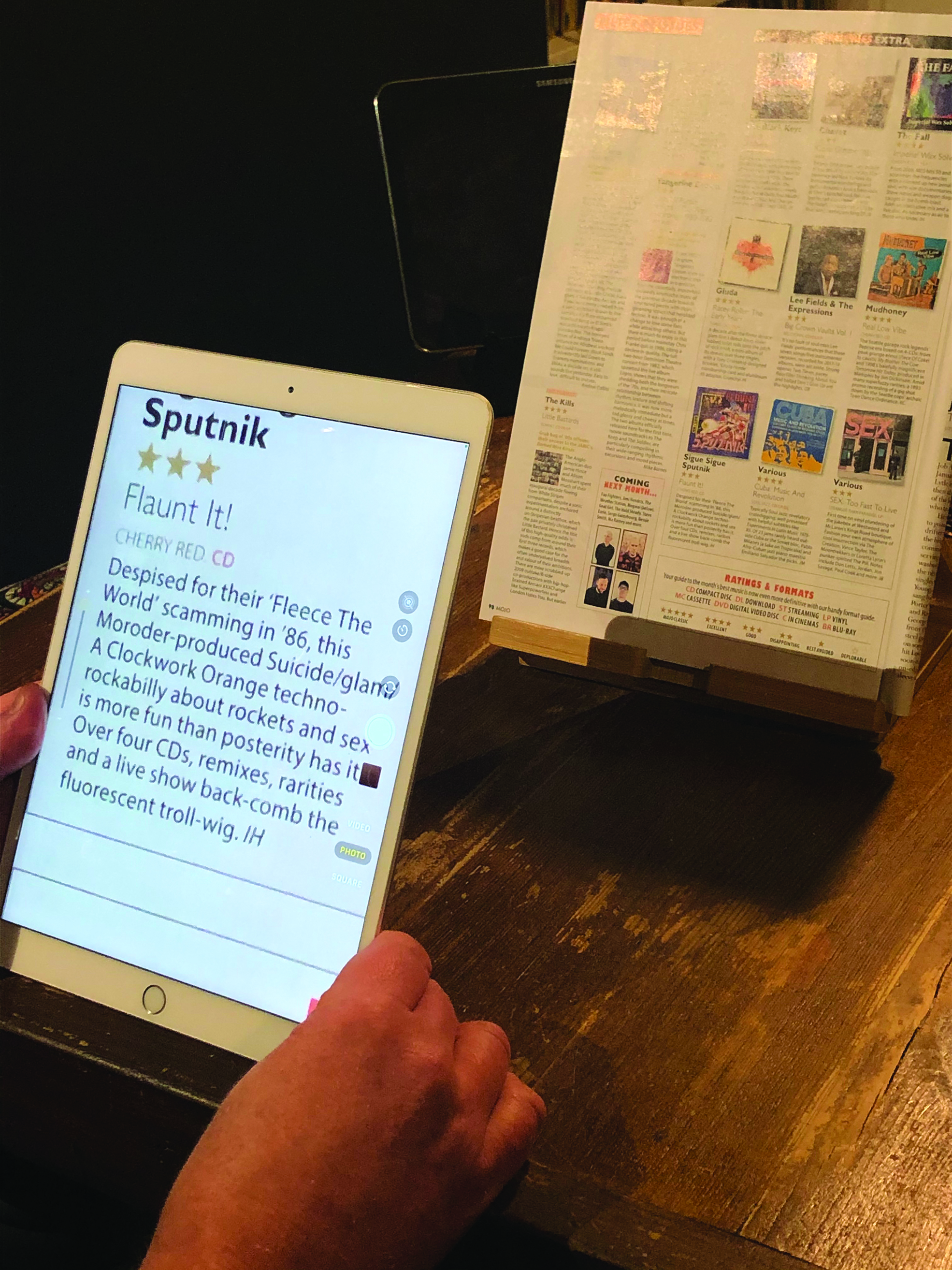

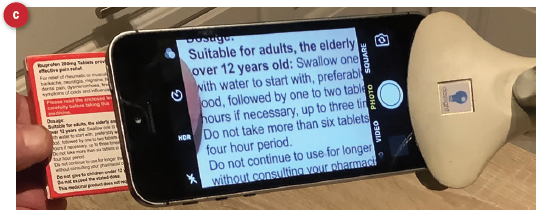

Screen clarity and camera resolution has improved in recent years to levels that allow for highly detailed images to be presented and magnified with very little loss of detail or clarity. This combination means tablets and smartphones can be adapted into a magnifying device, allowing the user to view a live image on-screen magnified to a suitable level, or to capture an image for later magnifying and viewing on screen when convenient. In this way, a smartphone may be used as a simple, portable magnifier for reading text (figure 7) or uneven objects (figure 8). The actual magnification achievable will be dictated by the size of the screen and the model of smartphone as well as the positioning, the latter having some flexibility because of the autofocusing of the camera. That said, four to five times is easily achieved.

Figure 7: Using the smartphone camera as a hand-held magnifier

Figure 7: Using the smartphone camera as a hand-held magnifier

Figure 8: Magnifying an uneven surface

Figure 8: Magnifying an uneven surface

Smartphones (and some tablets) include a light source, the one that is used as the flash by the camera. When used in isolation, the device can be used as an easily positioned, portable task lamp. I know of several elderly patients who use their phone simply as a hand-held task lamp when reading with their spectacle magnifiers, finding the positioning easy even for the closer working distances required.

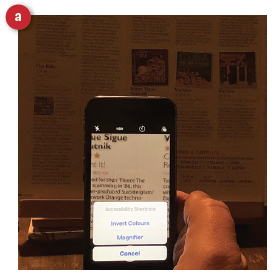

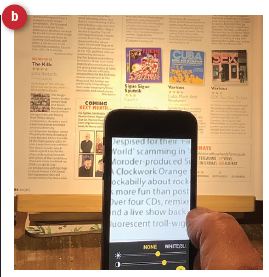

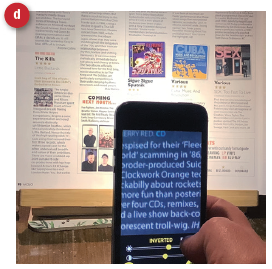

When using the camera as a magnifier, the light is usually no longer available as the software only employs it as a flash source when images are being captured. This problem has been overcome by a more recent accessibility update available on iPhones and which can be activated in the settings by switching on ‘magnifier’. This then allows the user to turn on the magnifier at any time by three rapid clicks of the smartphone button (figure 9a). The magnifier adaptation takes over the camera but now allows the user to use the light with the magnified image (figure 9b), use a range of colour contrast filters (figure 9c), reverse contrast (figure 9d), and increase the magnification to a much higher value than allowed by the camera on its own (figure 9e). The ‘3 click’ magnifier is very popular with iPhone users who have visual impairment.

Figure 9: (a) Three clicks of the button opens the magnifier option on an iPhone. This allows the user to select (b) illumination, (c) a range of colour filters, (d) reverse contrast and (e) greatly increased magnification

Figure 9: (a) Three clicks of the button opens the magnifier option on an iPhone. This allows the user to select (b) illumination, (c) a range of colour filters, (d) reverse contrast and (e) greatly increased magnification

Support and Stands

Viewing a magnified image with a handheld device, whether a tablet or smartphone, is made more difficult by hand tremor and this tends to worsen the longer the viewing proceeds. Use of both hands often helps (figure 10), as can taking a still image or video for subsequent viewing on another, stable device. A tablet has the significant advantage of offering a wider field of magnified image (figure 11) but is yet more difficult to hold steadily for any period of time, even with both hands.

Figure 10: Two hands reduce image shake

Figure 10: Two hands reduce image shake

Figure 11: Using a tablet camera as magnifier

Figure 11: Using a tablet camera as magnifier

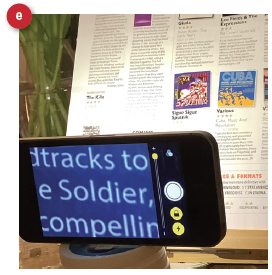

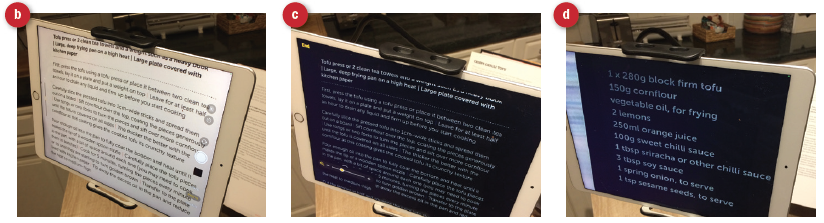

Another, in my view better, option is to employ some form of flexible stand. Double-ended flexible bulldog clips (figure 12a) can be useful for positioning hand magnifiers to allow hands-free tasks, such as needle threading (figure 12b). With care not to damage the screen when setting up, they can be similarly used with a smartphone set on camera or magnifier mode (figure 12c). A better option still is a flexible stand designed for use with a smartphone or tablet (figure 13a). These sturdy, fully adjustable units can be secured to any stable surface edge and then manoeuvred to the desired position. Costing just £10 to £15 from bookshops and online retailers means that a patient may have several set up around the house; one in the kitchen for viewing recipes (figures 13 b to d), one in the bedroom for late night reading and one in the bathroom for checking medicines. The patient then simply inserts their portable device into the appropriate, pre-positioned stand.

Figure 12: (a) Double-ended bulldog clip; (b) hands-free use of a hand magnifier; (c) hands-free use of a smartphone

Figure 12: (a) Double-ended bulldog clip; (b) hands-free use of a hand magnifier; (c) hands-free use of a smartphone

Figure 13: (a) Adjustable tablet/smartphone stand; (b) tablet camera magnification; (c) reverse contrast using ‘magnifier’ setting (d) good field of view, even at high magnification levels

Figure 13: (a) Adjustable tablet/smartphone stand; (b) tablet camera magnification; (c) reverse contrast using ‘magnifier’ setting (d) good field of view, even at high magnification levels

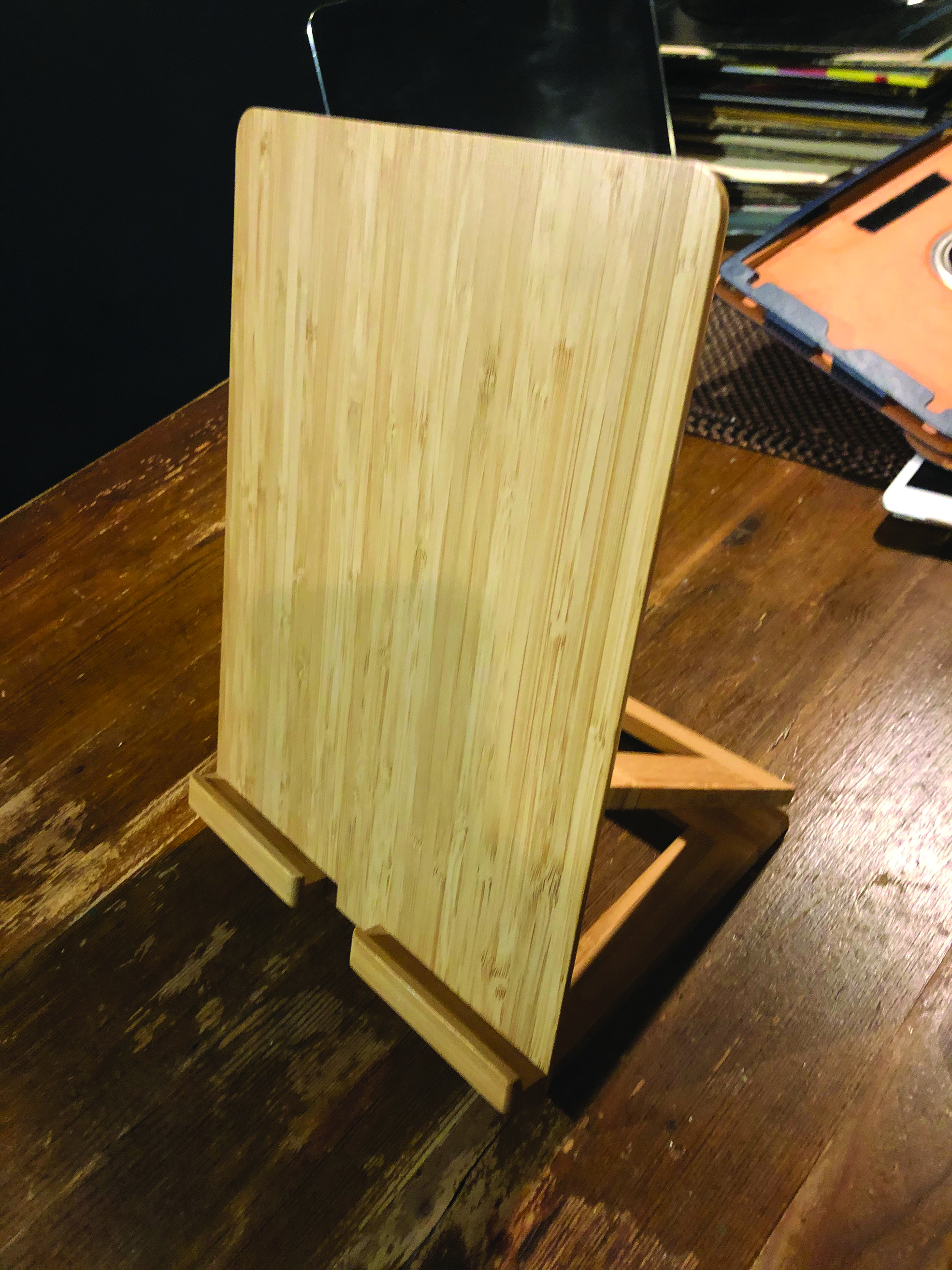

Just as I would rarely issue a stand magnifier without a clipboard, I usually recommend a reading stand for those interested in developing magnification options with their electronic devices. These vary widely in price and complexity, but I have had great success using a simple wooden stand that can be bought for not many pounds from a certain Swedish furniture store (figure 14).

Figure 14: A simple, cheap, but very effective reading stand

Figure 14: A simple, cheap, but very effective reading stand

Linking to Screens

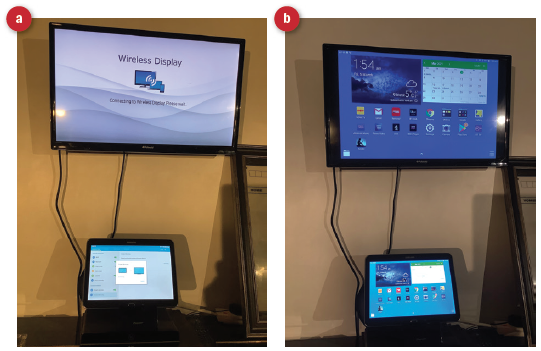

Wireless connectivity has become standard to electronic equipment and it is rare to find a tablet that cannot transfer its display to another screen. Most modern televisions offer a wireless option under their ‘source’ or ‘connection’ setting. Once selected, it is then simply a matter of going into the settings option on the tablet and choosing the ‘screen mirroring’ or ‘remote screen’ option. Once connected, anything displayed on the tablet is also seen on the TV screen, and where the latter is large, the level of magnification that is possible is increased yet more (figure 15). Apple devices connect easily to Apple TVs, but will require a plug in to connect with other TVs.

Figure 15: (a) Select wireless link options on TV and tablet; (b) displaying the tablet home screen on the TV

Figure 15: (a) Select wireless link options on TV and tablet; (b) displaying the tablet home screen on the TV

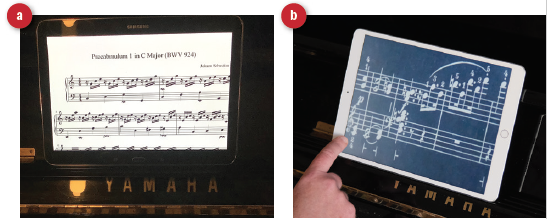

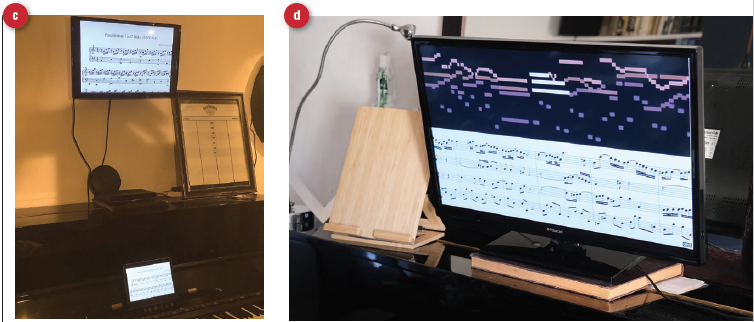

I have a patient who, having given up for some years, has restarted playing the piano by novel use of screens (figure 16). He knows how to use a tablet to scan or download sheet music, change to reverse contrast when he wants and then use as if sheet music but now able to be magnified. His wife can scroll the screen image just as she used to turn the pages of his music books. Linking his tablet with a screen positioned above the piano allows greater magnification still and also, by opening YouTube on the tablet and selecting the ‘connect device’ within the app, he is able to run video/animation manuscripts that auto scroll through the script at the correct speed. There are lots of these freely available on YouTube.

Figure 16: (a) Displaying sheet music on a tablet; (b) use of reverse contrast and scrolling when magnified; (c) link with TV over the piano for improved magnification; (d) manuscript animation displayed via linked tablet running YouTube

Figure 16: (a) Displaying sheet music on a tablet; (b) use of reverse contrast and scrolling when magnified; (c) link with TV over the piano for improved magnification; (d) manuscript animation displayed via linked tablet running YouTube

Bill Harvey is a specialist optometrist at the RNIB.

- The third article in this series will focus on electronic readers, dedicated apps and specialist software that can help those with a visual impairment

Resources

An essential resource is the RNIB Technology resource hub, which can be reached at www.rnib.org.uk/practical-help/

technology/resource-hub. This includes clear information and extra resources on:

- TV adaptations, audio description, large print TV guides etc

- Phones, tablets and desktop adaptation

- Specialist access technology – Braille display, screen readers, screen magnification, smart glasses and head-mounted

cameras - Home assistance – speaker driven assistance for access to media and electrical appliance control

Wherever you are in the UK, if you have a patient who might benefit from skilled advice on computer set up, they can contact the RNIB helpline (0303 1239999) and ask for the technology team.