At the start of this year, NHS Scotland made a request that optometrists participate in the Covid-19 vaccination programme. This was an extension of the role undertaken by some optometrists who had already been involved in administering flu vaccinations in the previous autumn. This article offers an account of what was involved in both the preparation for and then delivery of the vaccine, and will highlight the value of inter-professional support to deliver this national programme. Though there will be some detail about vaccines in general, the focus throughout is very much on the delivery of a vaccine by an eye care professional.

Towards the end, I have outlined several fictionalised case studies to help illustrate some of the challenges that may require evidence-based decision to address appropriately.

Background

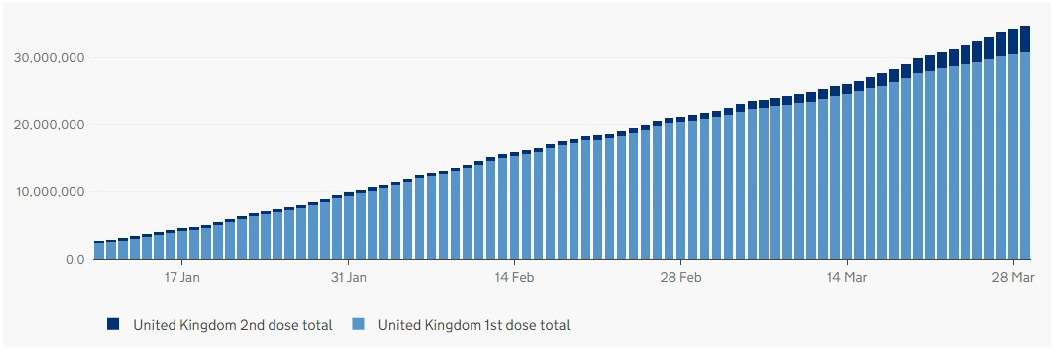

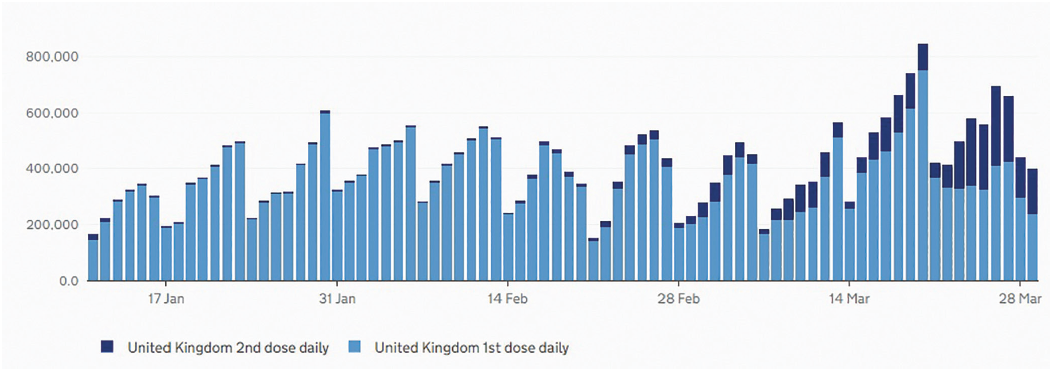

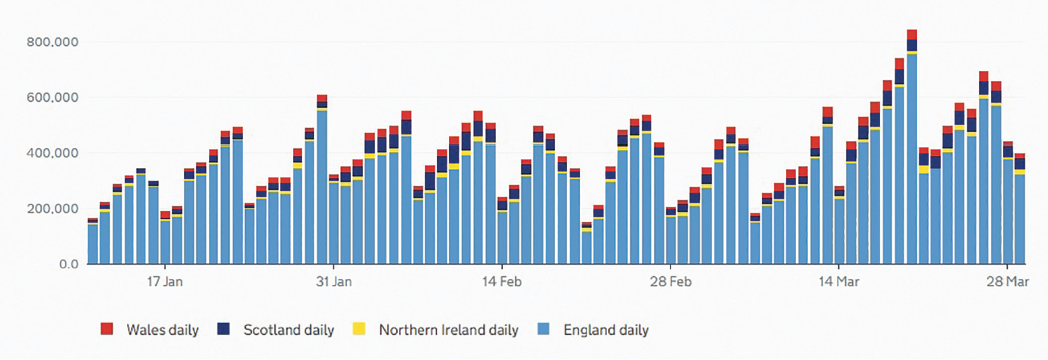

As of the March 30, 2021, the total number of people throughout the UK who have received the first dose of the two-dose vaccination is 30,680,948. The second dose total is 3,838,010.1 Since the start of this year, there has been a steady increase in the number of people vaccinated with their first dose and the cumulative number is now appearing to include a steadily increasing number having received their second dose (figure 1). The upward gradient and even profile of this curve has been achieved by the daily administration of anything between around 200,000 and 800,000 doses of vaccine each day (figure 2). This impressive programme has been rolled out throughout the UK as can be seen in figure 3.

Figure 1: Cumulative number of vaccine doses issued throughout the UK

Figure 1: Cumulative number of vaccine doses issued throughout the UK

Figure 2: Daily vaccine dose numbers

Figure 2: Daily vaccine dose numbers

Figure 3: Daily vaccine doses in the UK by nation

Figure 3: Daily vaccine doses in the UK by nation

This has required a major logistical programme and the efforts of a wide range of suitably trained health care professionals, newly enabled to support the programme by some deft changes to the regulatory legislation.

Patient group direction

According to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), ‘a patient group direction (PGD) is a written instruction for the sale, supply and/or administration of medicines to groups of patients who may not be individually identified before presentation for treatment.’2

PGDs are not a form of prescribing, but instead allow health care professionals specified within the legislation to supply and/or administer a medicine directly to a patient with an identified clinical condition without the need for a prescription or an instruction from a prescriber. The health care professional working within the PGD is responsible for assessing that the patient fits the criteria set out in the PGD. The supply and/or administration of medicines under a PGD cannot be delegated – the whole episode of care must be undertaken by the health care practitioner operating under the PGD.2

Existing regulations, specifically regulation 174 of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012, allow temporary authorisation for the supply of a medicinal product for use in specific circumstances. With the rapid development of vaccines against the Covid-19 disease and the need for widespread distribution and inoculations, regulation 174 has facilitated the roll out of the new drugs. So, all the approved Covid-19 vaccines, and some other vaccines such as the Flublok recombinant influenza vaccine, have a temporary license and therefore can be administered under a PGD since they are not unlicensed medicines.

In November 2020, an amendment to regulation 174 was introduced that allows for the inclusion of medicinal products with a temporary authorisation 174 to be included within a PGD. Throughout Scotland, and in areas identified as having greater need such as the north-west of England and London, local NHS services were established under PGDs, which included optometrists in the list of suitable health care professionals for vaccine delivery.2,3

A note on vaccines

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The term vaccination describes the introduction of the vaccine into a recipient in order to establish their immunity to the specified infection.

At the time of writing, there are two main vaccines in circulation but several more are to be approved and used in the coming months. Though all adhere to the basic definition of a vaccine given here, the new vaccines differ in the way they work, in their storage and preparation (often strongly dictating cost differences) and in their efficacy and safety profiles. The British Society for Immunology has made available an excellent resource that explains vaccines and might be useful for patient education.4 Here are some key points about the various types of vaccine against Covid-19.

Viral vector vaccines

- How they work; these use an unrelated, harmless virus that has been modified to deliver SARS-CoV-2 genetic material. The delivery virus is known as a viral vector. The delivered material triggers the cells of the patient to make a specific protein that the body recognises as pathogenic and results in an immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This response builds immune memory, so the body can fight off SARS-CoV-2 in future.

- Points of interest; they trigger a strong immune response. Some need storage at specific low temperatures.

- Examples; Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine, Ebola vaccine and the Jannsen (J&J) vaccine still under trial.

Nucleic acid vaccines

- How they work; these contain a segment of genetic material of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, either RNA or DNA, which is used by the patient’s cells to make a specific protein that the body recognises as pathogenic and results in an immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. This response builds immune memory, so the body can fight off SARS-CoV-2 in future.

- Points of interest; fast to develop so important in cases where variants are likely. Some need storage at specific low

temperatures. - Examples; Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Covid-19 vaccines.

Protein vaccines

- How they work; these contain proteins from the SARS-CoV-2 virus that are recognised by the immune system and triggers a response. This response builds immune memory, so the body can fight off SARS-CoV-2 in future.

- Points of interest; previous safety profiles are excellent. They are usually administered with an adjuvant to boost an existing immune response. An adjuvant is a drug or other substance, or a combination of substances, that is used to increase the efficacy or potency of certain drugs.

- Examples; Hepatitis B vaccine, the (still under trial) Novavax and the Sanofi GSK Covid-19 vaccines.

Inactivated vaccines

- How they work; these contain already inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus. This is recognised by the immune system and triggers a response. This response builds immune memory, so the body can fight off SARS-CoV-2 in future.

- Points of interest; these may need to be administered with an adjuvant to boost the required immune response.

- Examples; Influenza vaccine, the (still under trial) Sinovac and Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccines.

Attenuated vaccines

- How they work; these contain weakened SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is recognised by the patient and triggers an immune response, but not one strong enough to cause illness. This response builds immune memory, so the body can fight off SARS-CoV-2 in future.

- Points of interest; this long-established approach requires extensive trialling and time to ensure the response, which resembles that of an infected person, is appropriate.

- Examples; oral polio vaccine, the (still under trial) Codagenix Covid-19 vaccine.

Training

In August 2020, when lockdown restrictions allowed with social distancing and full PPE, I attended a meeting in a secondary care facility with other peers where we were to be trained in delivering vaccines in adherence to a set curriculum.5

We used a simulated model to practice intramuscular injections after being shown how best to assess the patient and choose the best site for intramuscular injection. Other aspects of training included:

- Overview of immunity and how vaccines work

- Consent procedures

- Vaccine storage, distribution and disposal

- Immunisation procedures by nurses and allied health professionals

- Contraindications and special considerations, immunisation and underlying medical conditions

- Vaccine safety and adverse events reporting, surveillance and monitoring

In addition to the above, in January 2021 I was required to undertake clinical governance training using the e-learning TURAS portal on the National Education for Scotland (NES) website. This evidence-based knowledge expanded on previous training with such topics as hand hygiene and relevant infection prevention, communication with patients and parents, legal aspects of vaccination (including incident response and reporting in cases of procedural error such as needle stick injury), anaphylaxis and other adverse events, and basic life support including CPR.6 Further advice on the minimum standards for immunisation allowed a competency assessment tool to be employed.7

Vaccination Centres

After registering on a healthcare app called Allocate bank, shifts could be booked in four-hour slots; either 08.00-12.00, 12.00-16.00 and 16.00-20.00. You could work one, two or three shifts per day if these were available. Locations of the centres were spread around our Lanarkshire NHS health board, so the initial cohort of elderly patients could attend centres that were local and easily accessible by public or private transport. These were usually community centres manned by both council and NHS staff. Indeed, Health Secretary Matt Hancock visited one of these centres near the start of the programme to see first-hand how Scotland was rolling out the vaccine.

In recent weeks, these local vaccination hubs have been closed to allow much bigger hubs to vaccinate the greater numbers of the public who are likely to be more mobile in the decreasing age groups as outlined by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).8

Vaccine Administration

Ideally, the vaccine should be administered into the deltoid muscle of the upper arm, some 2.5cm (two fingers’ width) below the acromial process, to avoid injury. This is best done by visualising an inverted triangle that extends from the base of your two fingers with the injection site in the centre of this triangle. Injection is by the insertion of the needle at right angles to the surface (figure 4). A 25mm needle length is standard, while a 38mm length needle is needed for adults with more fat covering their muscles.

Figure 4: Insertion of the needle at right angles to the arm surface

Figure 4: Insertion of the needle at right angles to the arm surface

For any patients with a bleeding disorder, a 23 or 25-gauge needle should be used, followed by the application of firm pressure and a cotton pad taped to cover the injection site. If there is insufficient muscle mass, or for any developmental reason, the vastus lateralis muscle in the anterolateral aspect of the thigh is a useful alternative injection site.

Vaccinators work within a PGD for each vaccine. During the clinic, each will receive a bottle of the vaccine. It is their responsibility to ensure cleanliness of their station and to draw up the correct strength of vaccine. Presently, these are:

- 0.5 or 0.4ml in a 10 or eight-dose vial for Oxford/AstraZeneca

- 0.3 ml in a six-dose vial of Pfizer-BioNTech. In addition, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has to be reconstituted by inverting the vial 10 times and using 1.8ml of 0.9% saline to dilute it before inverting another 10 times prior to use. When reconstituting the vaccine, this must be done within two hours after removal from storage.

Learning throughout each clinic included recoding when the first dose of each vial was administered as they had to be discharged into the sharps bin if six hours were exceeded before all was used (figure 5). However, this rarely occurred. Also, having the correct number of syringes for each vial in a tray is a good way to determine that you are administering the correct dosage, as no residual vaccine should be left in the vial.

Figure 5: A sharps bin for safe equipment disposal

Figure 5: A sharps bin for safe equipment disposal

Patient consent is attained only after outlining the common side effects of the vaccine, such as the following:

- Tender injection site

- Tiredness or flu-like symptoms, including fever (over 37.8 degrees) for up to 48 hours

The patient was given a vaccination booklet and advised that they could take a mild analgesic, such as paracetamol, if required. Of note, more patients have recorded these side effects after the second dose, although no patients vaccinated to date have suffered serious adverse responses in my experience. Even with recent media scares about blood clots after vaccination, to my knowledge no patient has refused the vaccine offered and they cannot request one vaccine over another. However, it is important to continually review updated information, such as that offered by the MHRA.9 Here, for example, can be found information about seeking medical advice if a consistent headache, lasting more than four days, or bruising occurs after receiving Oxford AstraZeneca. However, it is always important to remember the benefits of vaccination outweigh the risk of these rare side effects.10 Reporting adverse reactions after 48 hours of administration can be made using the MHRA hotline 0800 731 6789 or online www.coronavirus-yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk.

Once someone has received the vaccine, they can give blood as a donor some seven days after the jab as long as they feel well and have not had any extended reaction to the vaccine over 48 hours. You can also donate whole blood if you previously had Covid-19 to help to improve lives for the general population, although the recent recovery trail showed that convalescent plasma from these patients had no effect on the outcome if given to patients in intensive care with Covid-19.

Basic Life Support

A good way to remember cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is 30:2 (as in a visual field). This represents:

- 30 chest compressions

- Two rescue breaths after you have called emergency services and before any automated external defibrillation (AED)

Logistics

At the start of any shift, we have a team meeting to allow any updates to be discussed. Teams are split up into administrators, approvers and vaccinators. To be an approver you have to be at least a band five nurse or an allied health professional such as a dentist, optometrist, pharmacist or GP. As such, most of my day is spent assessing patients using a tablet to record the process. Firstly, after they have been registered by an administrator, you have to determine if the patient is suitable for vaccination and then to record consent before moving on to vaccination. Afterwards, patients are informed that the vaccine itself does not mean they cannot spread the virus so national policies such as social distancing and meeting with other people should be followed.

Case Studies

Case study 1

A 17-year-old male patient with a pacemaker fitted attended asking which vaccine he would be administered. In most hubs, the vaccine used has been the Oxford AstraZeneca. However, this vaccine has an exclusion criterion of under 18 years of age. As such, they were offered the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine as they were over 16 years of age and had no other contraindications, such as acute febrile illness, Covid-19 signs of symptoms in the past 48 hours or any evolving neurological condition.

The patient was not on any immunosuppressive drugs, which in itself is not a contraindication but can result in a reduced immune response to the vaccine. This patient will be offered the same vaccine as a second dose as there is no evidence on the interchangeability of the Covid-19 vaccines although studies are under way.

Case study 2

A 28-year-old female patient could not confirm her pregnancy status but stated she had been trying to conceive for some time. Although there is no evidence to suggest Covid-19 vaccines affects fertility, these vaccines have pregnancy noted as an exclusion criteria as routine testing of the vaccines was not administered to this sub-group.

However, vaccination in pregnancy could be considered where the risk to exposure to Covid-19 is high and cannot be avoided or where the woman has underlying conditions that place her at very high risk of serious complications of Covid-19. This was the case for this individual, however she was asked to contact her GP and reflect on the conversation and to seek an obstetrician’s view should she be confirmed as pregnant prior to vaccination.11

Current opinion is to give the first dose after the first trimester, unless there is a high risk of Covid-19. For women who get the first vaccination and within the next 12 weeks get confirmation of pregnancy, they should wait until they are no longer pregnant unless at high risk of Covid-19. Breast feeding women or those planning to breastfeed may be offered the vaccine as there is no known risk associated with non-live vaccines transmission from mothers to babies.

Case study 3

A 45-year-old male patient with asthma was flagged up as potential anaphylaxis as they have required oxygen previously after hospitalisation. The patient was informed that a dedicated anaphylaxis station was set up and that if any adverse event occurred direct ambulance facilities to a nearby A&E hospital would be organised. They were also advised to get the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine, which has a lesser adverse reaction to this sub group and were not knowingly allergic to any components of the vaccine.

As an additional precautionary measure, the patient was asked to wait in the recovery area for 30 mins rather than sit on their own in their car. This recovery area is usually only required for patients administered the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and is usually only 15 mins. There have, however, been extremely rare reports of systemic allergic reaction to the vaccine requiring 0.5ml of adrenaline to be administered by an assessor with relevant training every five minutes. This prevents constriction of the airways and allows the patient to be seen in secondary care. In such cases a second vaccine should not be scheduled.

Case study 4

An 85-year-old male taking warfarin produced his vaccination card as he stated his control had been poor in recent weeks. His international normalised ratio (INR) was 4.1. This is above the cut off threshold of 4.0 that is used to reduce the risk of bleeding in surgery, such as cataract and dental techniques. However, the patient was very concerned about contracting Covid-19 and had been self-isolating. After discussing the risks, such as developing a haematoma, the patient consented and, after vaccination, he felt faint. He was put into a wheelchair, given water and was accompanied into the recovery area. He did have slight bleeding at the injection site and a pad and bandage were administered.

Case study 5

A 74-year-old female attended with a history of previous Covid-19 and taking part in a clinical trial for a Covid-19 vaccine although as part of the trail she was still unaware if she had been taking a placebo or the trial vaccine. Patients with previous confirmed or suspected Covid-illness are still encouraged to receive the vaccine. As this patient was no longer in a current clinical trial and was over 90 days from treatment, she was not excluded however she had also received another vaccination for influenza five days previous. Because of the absence of data on co-administration with Covid-19 vaccines it is recommended that the interval between vaccines should be at least seven days for Oxford AstraZeneca and 14 days for Pfizer-BioNTech. As such this patient was asked to return after 14 days in case the vaccination hub was only administering the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Recording of vaccines given within the last 6 months is also part of the data gathering for the vaccine programme.

Reflection

I have completed 11 sessions in the vaccination hubs to date. I have worked alongside fellow optometrists and friends and other AHPs such as dentists and GPs as well as bank staff of nurses, students and people from all walks of life who volunteered to be administrators and vaccinators. I consider it a privilege to work alongside such a dedicated NHS staff and the support shown by the public with many verbally praising you was overwhelming and reminded me of the positive force of human nature and togetherness. I would urge all optical workforce interested to volunteer if they can and be in it together.

Dr Scott Mackie is an Independent Prescriber, Dispensing Optician and Optometrist with independent practices in Lanarkshire. He has a contract with NHS Scotland as a AHP to support the Covid-19 vaccination programme.

References

- https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/vaccinations

- www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/what-is-a-patient-group-direction-pgd

- https://www.hps.scot.nhs.uk/publications/patient-group-directions

- www.immunology.org/coronavirus/connect-coronavirus-public-engagement-resources/types-vaccines-for-covid-19

- https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/immunisation-against-infectious-disease-the-green-book

- https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/2216/promoting-effective-immunisation-practice-peip

- http://www.nipcm.scot.nhs.uk

- https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/joint-committee-on-vaccination-and-immunisation

- https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/mhra-guidance-on-coronavirus-covid-19

- https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/immunisation/vaccines

- https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/44684/turas-vaccination-management-tool/what-s-new/scottish-government-communication-vaccinations-in-pregnancy