So far in this series we have looked at the many and various ways smartphones and tablets can be adapted to enable those with reduced vision to use them more effectively, primarily by making changes to their operating systems and by selective use of any in-built features, such as a camera. This article will offer an overview of some of the very many apps that may be downloaded onto smartphones and tablets that are designed to help the user with reading as well as general use electronic reading devices which have been available for some years now.

As all low vision practitioners well know, difficulty with reading is a major visual disability relating to the fact that loss of central vision is a major visual impairment. As an alternative to large print or magnified paper text, dedicated software and apps have revolutionised the way we read in ways that can really help the visually impaired. That said, devices solely dedicated to presenting electronic text, e-readers, are also popular as an alternative to adapted computers, tablets and smartphones and so shall be discussed first.

E-reading

There are a number of hand-held devices with the sole purpose of storing and displaying electronic versions of paper printed publications. These are e-book readers or e-readers. Their basic design includes a flat screen for text display and a memory chip able to store a vast number of publications easily downloaded a WiFi or USB link, both set in a flat casing of dimensions not dissimilar to a thin paperback book.

The Kindle (from Amazon) is the best known e-reader, but other widely used devices are available, such as models from Kobo, Nook, Sony and PocketBook. Though most features are common to all, it is worth knowing of a few different devices as variations exist that might be of benefit to any individual

patient.

While the majority of advantages over paper texts are shared with reading software on other multi-functional digital devices (storage capacity, text manipulation, remote upload and deletion, audio and speech linkage and so on), the main advantage of an e-reader is their display screen. E-readers use monochrome e-ink screens to display text, and the use of e-ink (or digital ink) onscreen is a much closer simulation of paper text, making reading for long periods more comfortable than viewing the radiant LED or OLED screens of other devices. Most have backlit screens with adjustable brightness which make them attractive to older patients, whether they have visual deficit or not, and this allows them to be easily read in all sorts of ambient environments, dark or bright. In all cases, e-ink is much easier to read in bright sunlight, while colour touch screens on tablets tend to wash out, and their glossy displays can show distracting reflections. There is little variation in screen size between different e-readers, ranging from the 15cm of some Kindles to the larger 20cm of some Kobo and Onyx devices, and most recent e-readers use the latest E-Ink Carta display technology with 300 pixels per inch. Teething problems of screen flashing, slow response to touch and poor text contrast have been addressed. This high resolution image quality, along with the fact that the units have one single function as an alternative to paper text, makes them a popular choice.

That said, there are disadvantages. Some people prefer having a single multifunctional device to having several different devices. Also, most e-reader models tie in to their own software, such as the way the Kindle requires an Amazon account. Whether run on an e-reader with its superior text display or as a downloadable programme on another device, the reader software is easy to adapt for the individual needs of the user.

I use an iPad in clinic and so have downloaded the free Kindle app. I have then downloaded a range of books via my Amazon account, many of which are free such as all those classics now out of copyright. This allows me to easily demonstrate to a patient with reduced vision advantages such as the following:

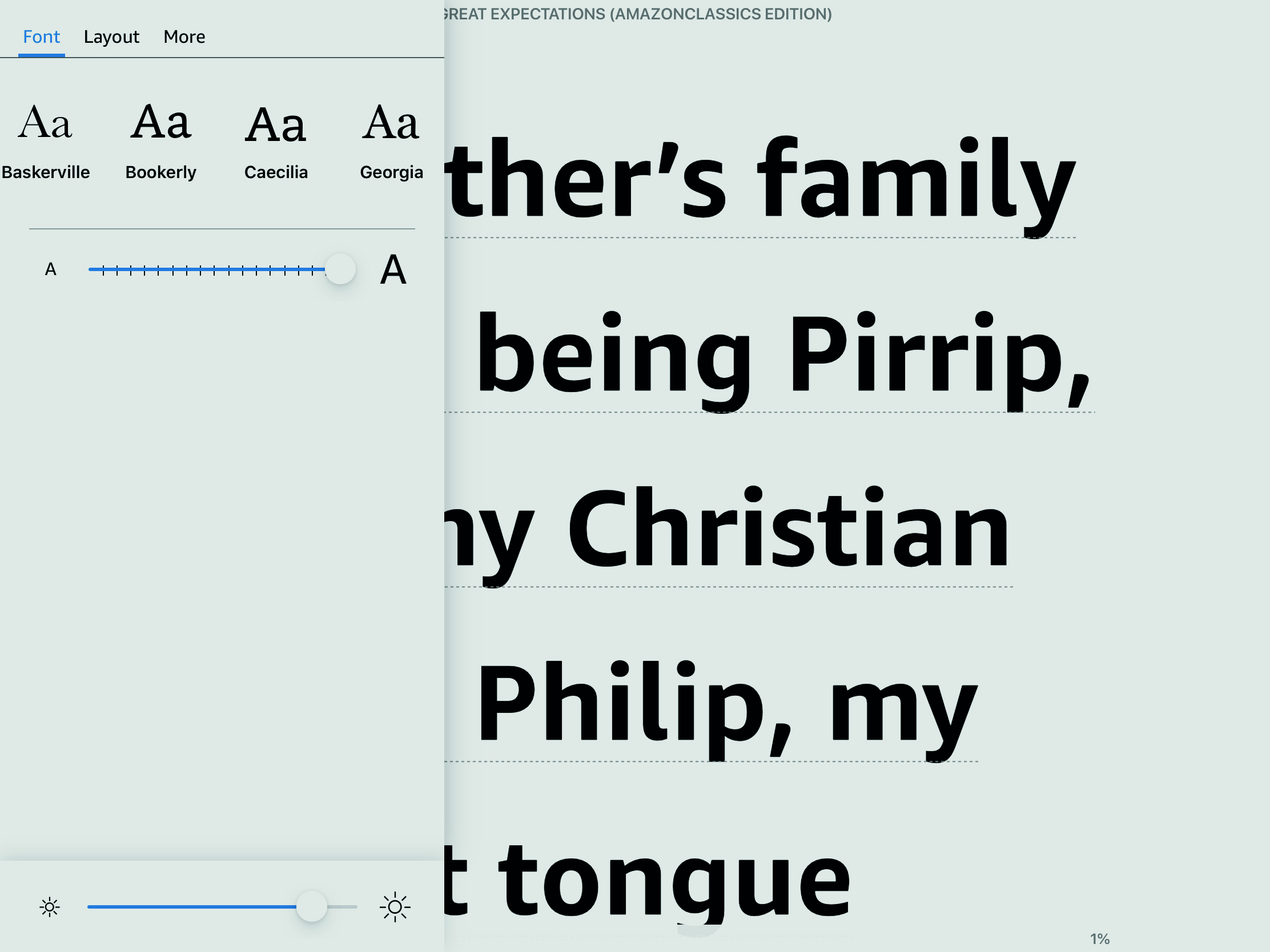

- Font; size, style, colour, line separation, overall formatting (figure 1)

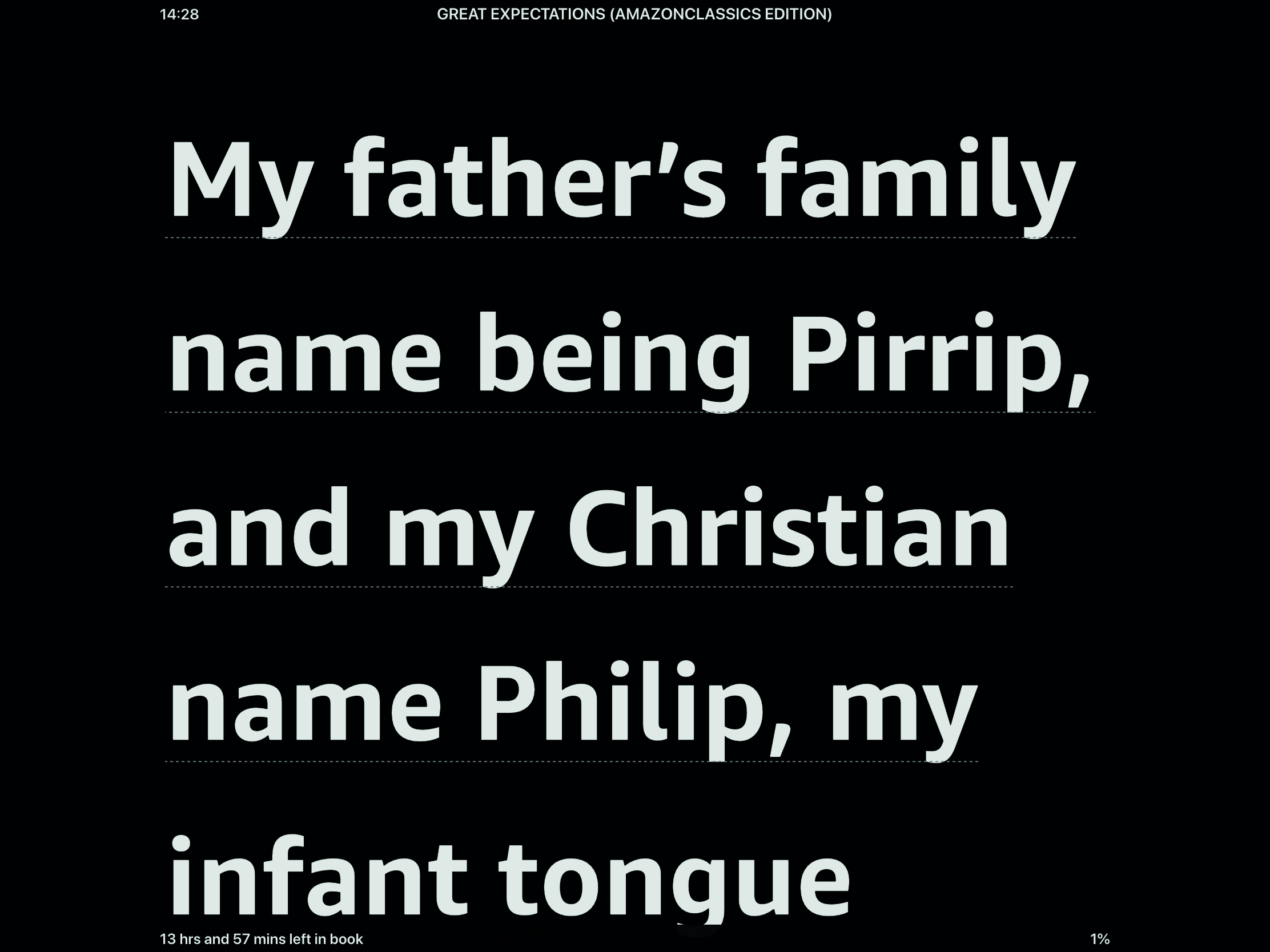

- Contrast enhancements; including reverse contrast (figure 2)

- Background colour and brightness change

- Typoscope text delineation

- Audio text-to-speech where available

Figure 1: Titles now out of copyright, such as Great Expectations, are easily downloaded to a Kindle and the font changed and magnified

Figure 1: Titles now out of copyright, such as Great Expectations, are easily downloaded to a Kindle and the font changed and magnified

Figure 2: Selecting the layout option allows changes to the spacing, paragraphing and background. Reverse contrast is a great help to many visually impaired people

Figure 2: Selecting the layout option allows changes to the spacing, paragraphing and background. Reverse contrast is a great help to many visually impaired people

‘But,’ I hear you cry, ‘it is just not the same as holding and reading a book or magazine.’ Here we enter into new territory and much research is yet needed before there is a definitive answer to the question of which format is ultimately preferable; paper-based or electronic. In my experience, even the oldest or most infirm visually impaired patients take well to e-readers, especially when I have pre-set them optimally and thoroughly explained their use. I can also send new titles to patients around the country, so minimising travel, chair and contact time. Patients who live alone and remote to their family really appreciate it when you show one of their relatives how to acquire a book on their own account and have it delivered direct to the patient’s device. However, nearly everyone still misses the sensual experience of holding a book and turning its pages.

The obvious assumption is that this is due to familiarity with the established medium from the time when first reading and, were this the sole reason, we might expect e-readers to soon establish themselves to eventually supersede paper. In fact, there is a growing body of evidence that traditional paper text may actually be preferable to electronically displayed text of a similar readability. I have listed some of the key studies into this at the end of this article and recommend you have a glance. They represent well-designed and refereed studies that suggest a range of benefits with paper-based texts including the following:

- Digital media is often associated with fast-paced and constant exposure information display, which encourages more rapid information processing and, as a consequence, poorer retention of detail. This is often named as the shallowing hypothesis.

- When scrolling through electronic text, the tendency to miss detail is much greater than when reading paper text.

- Turning the page is a distinct experience to scrolling a display and, whether it is related to nostalgia or not, usually influences a more positive reported experience with paper.

- Comparison trials show subjects better able to recall chronological narrative detail with paper than electronic text. Paper print provides sensorimotor cues that enhance cognitive processing. When holding a book, readers receive physical reminders of how many pages they have read and how many remain. They can also flip pages to reread text as needed. Some studies suggest readers process information more effectively when they recruit multiple senses, and multiple brain areas, during task learning; seeing the words, feeling the weight of the pages and even smelling the paper.

It is worth ECPs keeping abreast of this research so we can better advise our patients about an important visual task. For the visually impaired, the advantages of display enhancement and linked input will very often outweigh any preference of experience, and so adaptation to electronic display is to be encouraged in the same way as we have historically encouraged adaptation to the use of any magnifying device.

Reading apps

Software with specific application (an app) is easily downloaded onto smart digital devices. Many of these are easily adapted to benefit those with visual impairment, while many others are specifically designed with those people in mind.

Newspaper apps

Modern newspapers are readily available, either in a free online version funded by advertising and often with limited content, or as a subscribed electronic version, both easily viewed on any smart device. The larger screen of a tablet is preferred. It is the latter that I demonstrate to those visually impaired patients wanting help with newspapers, and many prefer this to a magnifier for reading their original paper versions. There are a number of reasons for this:

- The contrast of the screen display is far greater.

- It is easy to magnify the text on screen while maintaining a wider field of view than might be expected from the optical magnifier equivalent.

- There is greater overall convenience, with all pages and individual issues stored in one easily accessed and space efficient place having been delivered immediately via wireless signal. This has the added benefit of reducing clutter in the living space and removes the need for recycling.

- Accessibility functions of the digital device may be employed, such as use of VoiceOver (iOS), TalkBack (Android) or JAWS (Microsoft) which will read out the viewed text, contrast enhancement, reversal or colour contrast enhancement are all easily set up and will be applied to the newspaper being viewed.

- Physical convenience; it is easier to hold a flat, evenly lit screen than a flexible, unevenly contrasting newspaper and magnifier.

Readly

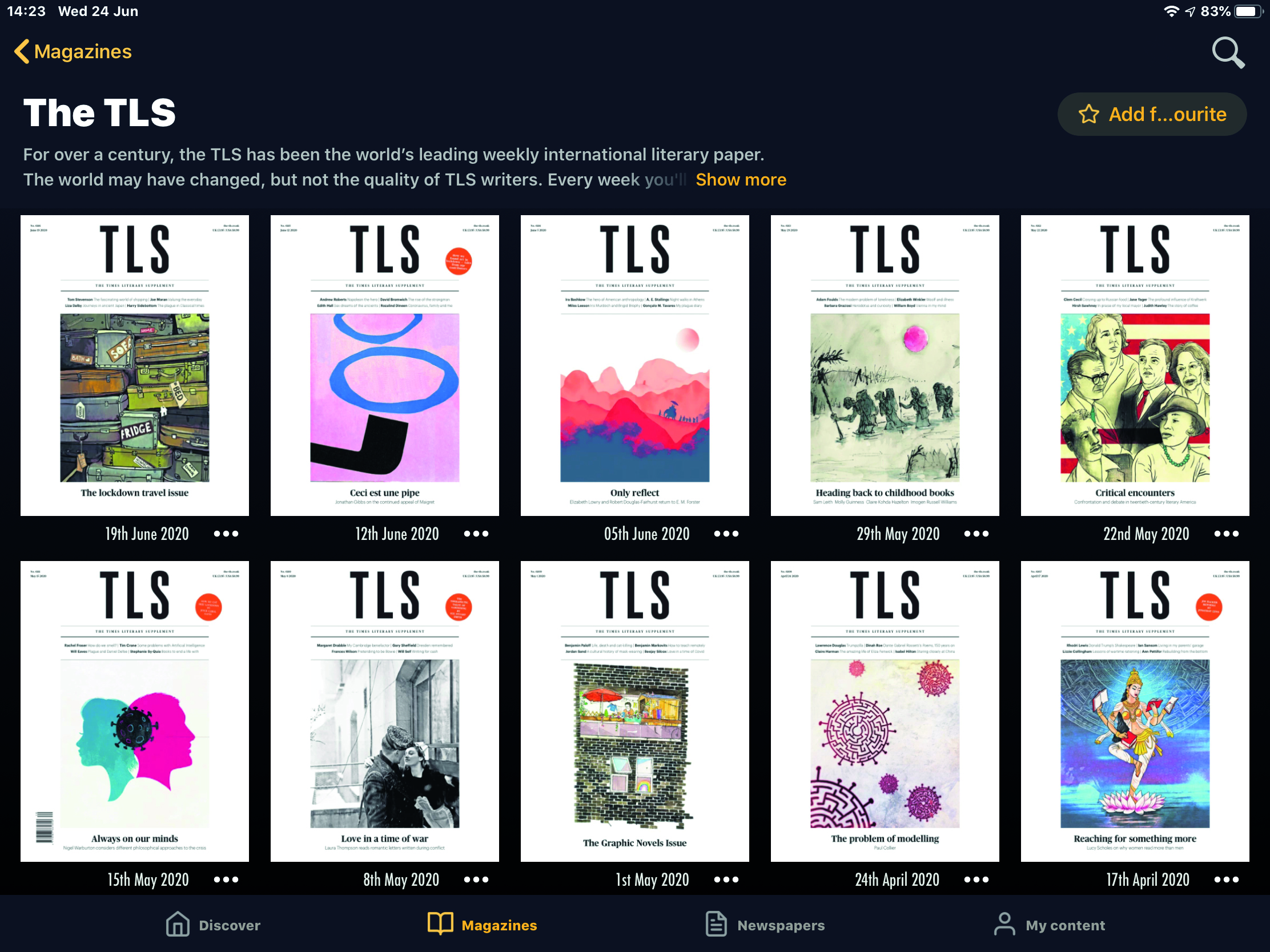

Of the various bulk title apps available, the one I have had greatest success with is Readly. Free to download, this app requires a small monthly subscription (under £10) to then make available an extensive range of magazines and newspapers, from the UK and a great number of other countries too; pretty well everything on the shelves of your local WH Smith store. I have had great success helping vastly different visually impaired patients with this app, whether a young retinitis pigmentosa patient who misses the rock music press or a retired teacher whose AMD prevented them reading their beloved Times Literary Supplement. As with the newspaper apps, the various publications are easily enhanced to improve their readability (figure 3).

Figure 3: Readly offers access to a wide range of magazine, newspapers and periodicals, such as (a) the Times Literary Supplement. (b) Once an issue is chosen, the view is easily enhanced using accessibility options

Figure 3: Readly offers access to a wide range of magazine, newspapers and periodicals, such as (a) the Times Literary Supplement. (b) Once an issue is chosen, the view is easily enhanced using accessibility options

Bible apps

There are several of these, each with a variety of features including text-to-speech options, language translation, text enhancements, explanatory notes, daily message service and so on. As is well demonstrated by the case study on page 26, these apps are quite literally a godsend to those patients for whom religious texts are important.

Libby

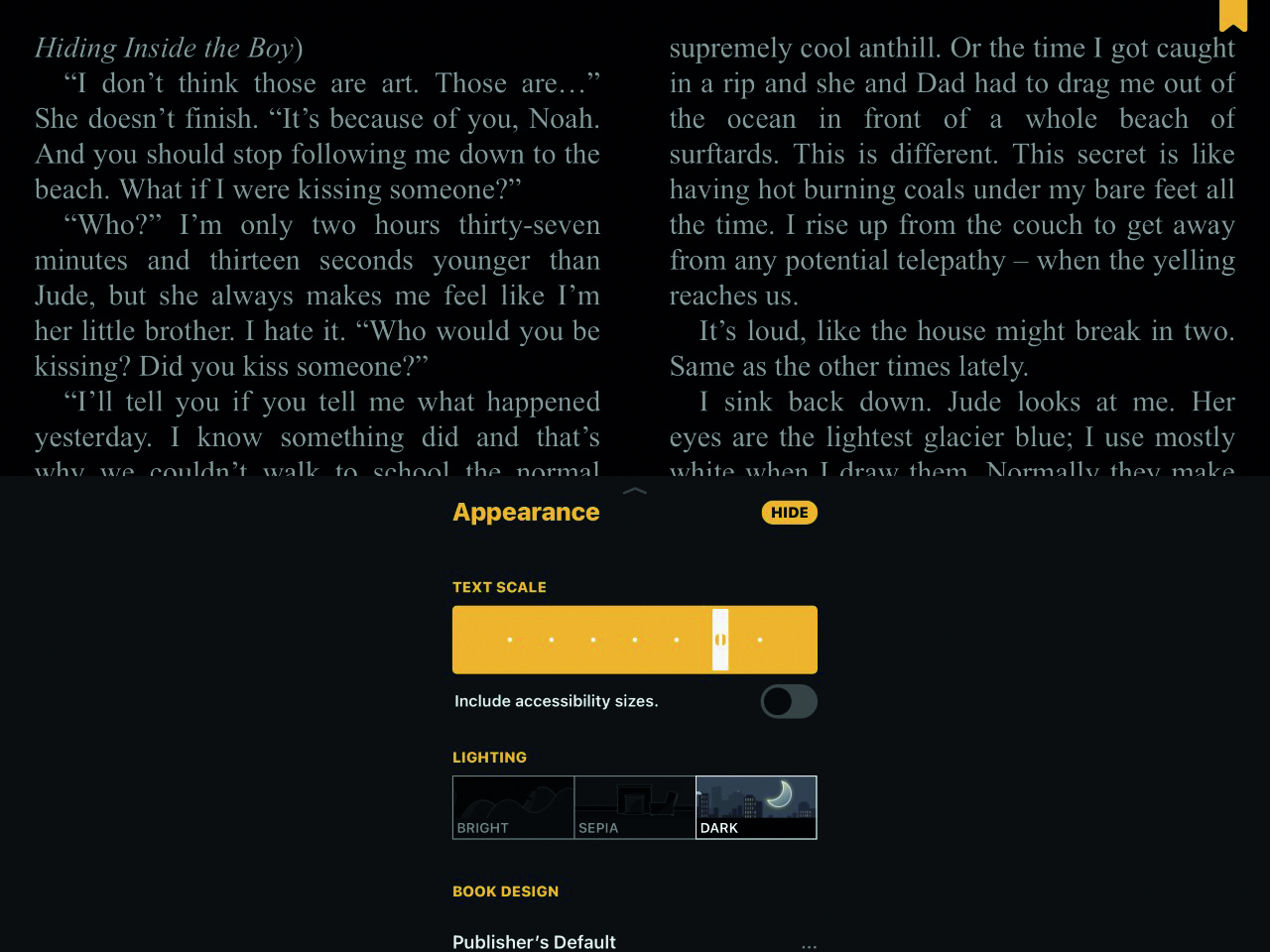

The Libby app is a way of linking up with the local library and then being able to borrow any text the library has in electronic format without having to leave the home. The text appears in the app for the length of the time of loan and has a great number of features that make the text more easily readable for those with visual difficulties (figure 4).

Figure 4: Once Libby is linked to a local library any of their electronic publication stock can be downloaded and modified for enhanced reading

Figure 4: Once Libby is linked to a local library any of their electronic publication stock can be downloaded and modified for enhanced reading

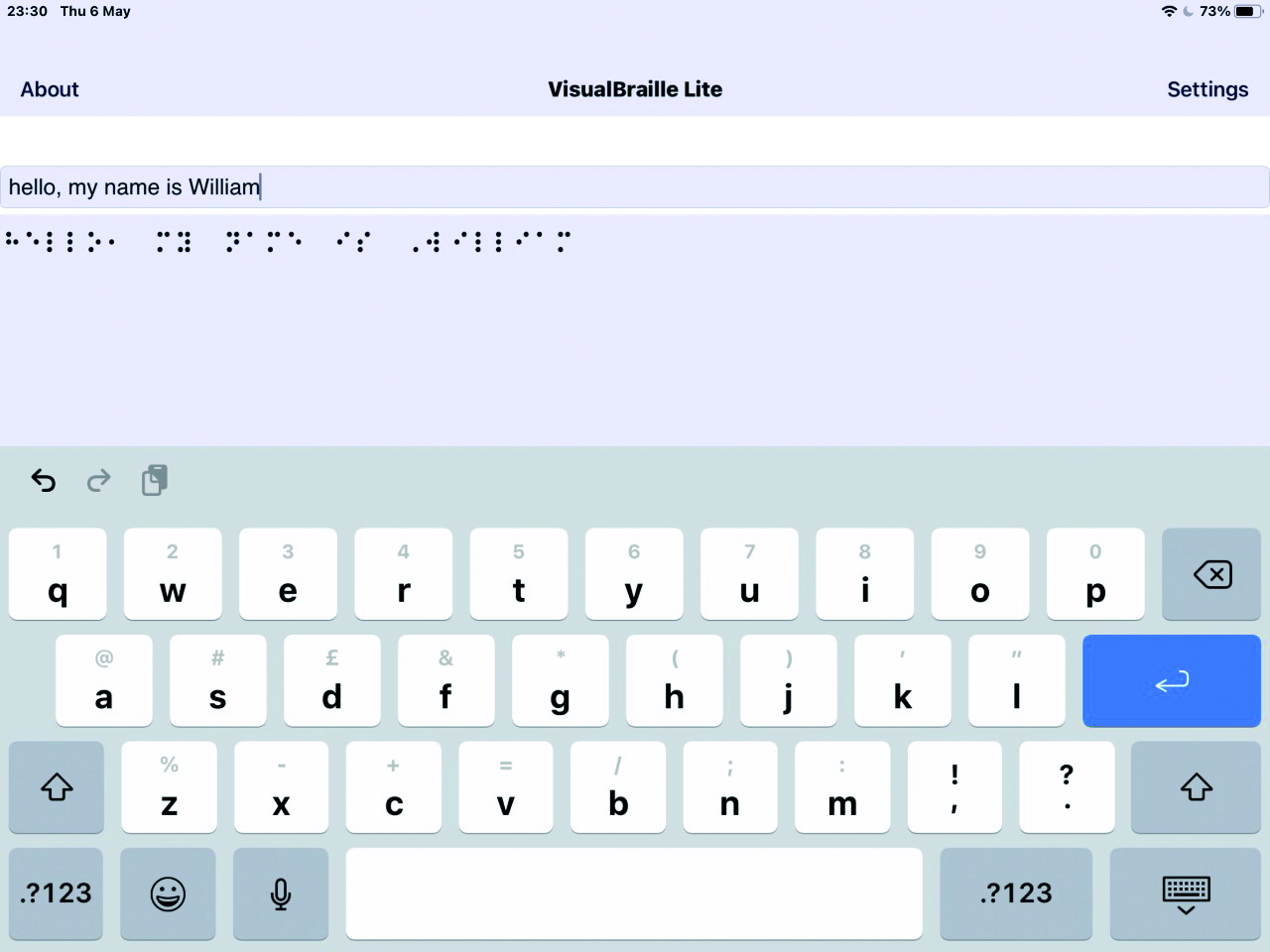

Braille readers

There are a number of apps that are designed to help the patient who reads braille, or indeed the ECP who may want to develop their braille skills. These range from free downloads able to translate written text into braille (figure 5) to increasingly expensive and comprehensive braille reader packages. As an example of how a reading app can be of assistance when dealing with much greater levels of vision loss, using the KNFB reader, available for both iOS and Android at a cost of around £100, I was able to capture text and convert it into speech or braille with a simple click of the tablet or smartphone operating button.

Figure 5: Converting text into braille

This final app, which is designed specifically to help those with challenges to their reading either through sight loss, cognitive impairment or reading difficulty, offers a taste of what is in the next article in this series where I will discuss some of the many apps I have found to be of use when managing patients with various levels of visual difficulty, and which can help with a wide range of tasks other than reading.

- Bill Harvey is a specialist optometrist at the RNIB

Resources

An essential resource is the RNIB Technology resource hub which can be reached at:

www.rnib.org.uk/practical-help/technology/resource-hub

Wherever you are in the UK, if you have a patient who might benefit from skilled advice on computer set up, they can contact the RNIB helpline (0303 123 9999) and ask for the technology team.

References

Note that this list is to support the first section of this article and comprises research comparing electronic and paper displays in terms of comprehension and readability. Each is of interest in revealing ways in which paper text display has advantages over electronic display.

- Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R., & Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: A meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educational Research Review, 25, 23–38

- Garland, K. J., & Noyes, J. M. (2004). CRT monitors: Do they interfere with learning? Behaviour & Information Technology, 23(1), 43–52

- Hou, J., Rashid, J., & Lee, K. M. (2017). Cognitive map or medium materiality? Reading on paper and screen. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 84–94

- Lauterman, T., & Ackerman, R. (2014). Overcoming screen inferiority in learning and calibration. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 455–463

- Mangen, A., Olivier, G., & Velay, J.-L. (2019). Comparing Comprehension of a Long Text Read in Print Book and on Kindle: Where in the Text and When in the Story? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 38

- Mangen, A., Walgermo, B. R., & Brønnick, K. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 58, 61–68.

- Mayer, K. M., Yildiz, I. B., Macedonia, M., & von Kriegstein, K. (2015). Visual and Motor Cortices Differentially Support the Translation of Foreign Language Words. Current Biology, 25(4), 530–535.

- Millward Brown Case Study – Using Neuroscience to Understand. (2009). Retrieved from; https://www.millwardbrown.com/docs/default-source/insight-documents/case-studies/MillwardBrown_CaseStudy_Neuroscience.pdf

- Singer Trakhman, L., & Alexander, P. (2016). Reading Across Mediums: Effects of Reading Digital and Print Texts on Comprehension and Calibration. The Journal of Experimental Education. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2016.1143794

- Smoker, T. J., Murphy, C. E., & Rockwell, A. K. (2009). Comparing Memory for Handwriting versus Typing. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 53(22), 1744–1747