Essential important documents for all registered optical practitioners and students, and unregistered optical workers, especially those with managerial responsibility, to familiarise themselves with include:

- The Opticians Act 1989; available at www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/opticians_act.cfm

- Sale of Optical Appliances Order of Council 1984; available at www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/rules_and_regulations.cfm

- Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians; available at https://standards.optical.org

Implications of Deregulation

The sale of all optical appliances to consumers (rather than between manufacturers and retailers) was first regulated in the UK under the Opticians Act 1958. In 1989, when the authors qualified, a new Act came into force and ophthalmic dispensing to most adult patients was derestricted such that unregistered sellers could supply prescription optical appliances subject to new regulations.

The Opticians Act 1989 (as amended 2005) provides the structure that regulates optometrists and dispensing opticians and gives them the power to sell optical appliances. While opticians should be fully conversant with the rules the Sale of Optical Appliances Order of Council 1984 applies only to the unregistered seller.

This means that any competent individual can sell spectacles/optical appliances, so long as they can abide by the 1984 Order. Unregistered sellers are, however, prohibited from supplying an optical appliance to a person in a restricted category. This includes:

- A person under 16 years of age

- A person registered as sight impaired or severely sight impaired

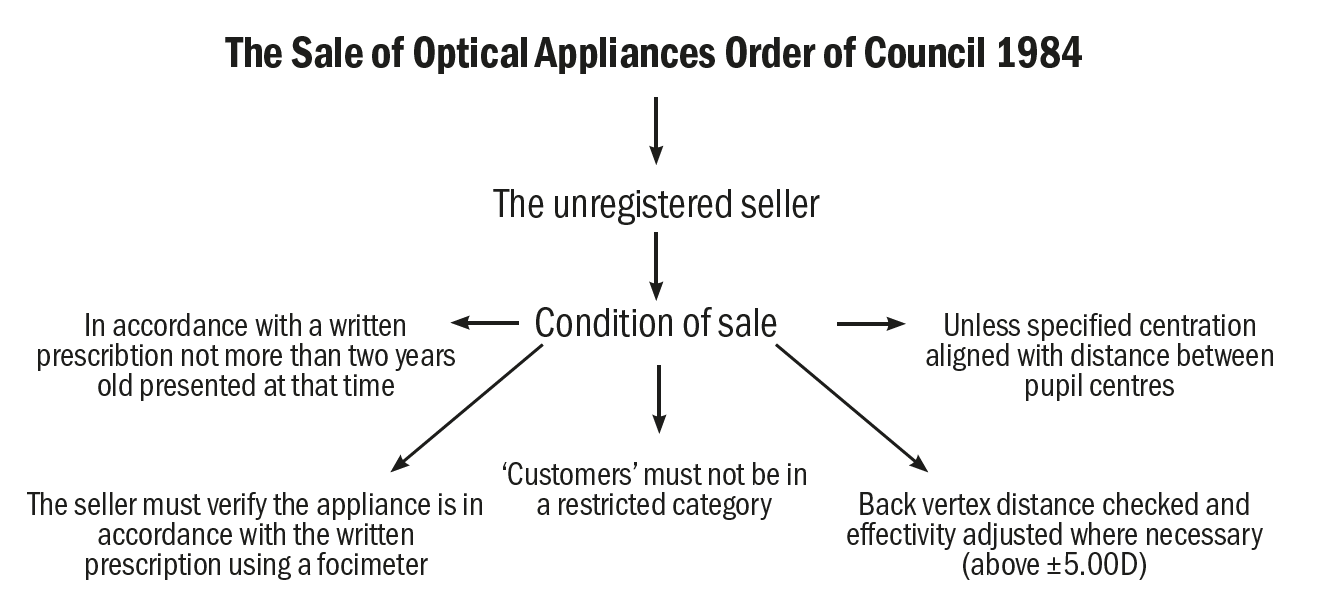

Assuming the purchaser is an adult and not sight impaired the sale may proceed subject to a range of conditions summarised in figure 1. These conditions are as follows:

- The sale must be in accordance with a written prescription that is not more than two years old on the date of presentation

- The seller must verify that the appliance is in accordance with the prescription by means of a focimeter

- The unregistered seller must, unless specified, align centration with the distance between pupil centres

- If the written prescription includes a vertex distance, then the seller must check the back-vertex distance and compensate for any effectivity errors

Figure 1: The conditions for the supply of an optical appliance as stipulated by the Sale of Optical Appliances Order of Council 1984

Figure 1: The conditions for the supply of an optical appliance as stipulated by the Sale of Optical Appliances Order of Council 1984

Non-registered Supply

There appears to be considerable confusion as to what constitutes a restricted category of patient when it comes to the supply of optical appliances that are neither contact lenses nor low vision aids; in other words, the supply of spectacles. Only two groups of patients are restricted; children under-16, and low vision patients who are registered as sight impaired or severely sight impaired with their local authority. Therefore, low vision patients who are not registered, or who chose not to declare their registration, do not require to be dispensed by or under the supervision of a registered optician.

Similarly, many registrants seem to be falsely under the impression that safety spectacles, lenses incorporating prism and high-powered lenses (those with sphere power over +/-10.00DS or high value cylinder) are also restricted categories. In fact, this is not the case, though it is clearly in these patient’s best interests to avail themselves of the services of a competent practitioner and this is often reflected in company standard operating procedures. However, there is nothing to stop an unregistered seller supplying these items.

Therefore, a failure on the part of a registrant working with unqualified colleagues to supervise scrupulously the dispensing of safety eyewear, high powered or complex prescriptions, would not be in breach of the law. However, failure to adhere to company policy or standard operating procedures might be a cause for concern for their employer. It should also be pointed out that, if something were to go wrong and the registrant be called to account, then it would likely as a matter of fact be shown that arm’s-length supervision was inappropriate in the case in question, unless the registrant had reasonable grounds to expect their colleague to be competent.

In dentistry and pharmacy, where tasks are delegated and close supervision is not appropriate, this quality assurance is given by ensuring all non-registered colleagues are suitably trained and certified. Although this does not absolve the registrant from due diligence, it does provide the registrant with some assurance that colleagues can carry out their role competently. Eye care is unusual among the regulated healthcare professions in the UK in not ensuring a minimum standard of competence for the various clinical support staff, optical dispensing assistants and optometric clinical assistants who accept delegated tasks, such as pre-screening, contact lens instruction and ophthalmic dispensing, from registered colleagues. Perhaps with optical assistant apprenticeship funding now available to the whole sector, this situation might change.

Consider the example where a prescription requires a back vertex distance and potential compensation of the prescription. Although technically this is not a restricted category for the dispensing of a patient, the task should only be undertaken by a person competent to measure the vertex distance of the frame and make the necessary modifications to the prescription as required. Support staff must know to work within their level of competence and to seek help when such prescriptions present. Alternatively, more complex dispensing should be reserved for more advanced non-qualified colleagues, such as a trainee dispensing optician, pre-registration optometrist or assistant qualified at level 3 or 4, if not being carried out by a qualified

registrant.

Case Study; Online Spectacle Sales

In the author’s opinion, the requirements of the 1984 Order translate to most online retailers of spectacles being in breach of the regulations for a significant proportion of sales. Websites do not collect supplementary information, such as back vertex distance (BVD). They choose to ignore the requirement to check whether a frame sits at a different vertex distance to that of the refraction since they are unable to do so without employing sophisticated smartphone or tablet camera applications with 3D scanning capability. Therefore, they cannot comply with the regulation that ensures for a change in back vertex distance ‘if it would be different [they make] any adjustment in the power of the lens to ensure that when in use it gives the optical effect required by the prescription’.

The 1984 Order refers to BS 2738:1962, since superseded by BS 2738-3:2004+A1:2008, which now applies and clearly states, in clause 4.1, that a back vertex distance is required to be recorded on prescriptions above +/-5.00DS ‘to allow the person subsequently dispensing the spectacles… to make any necessary adjustments to the power ordered’.

Since websites routinely make no attempt to compensate for vertex distance, it seems that many are acting illegally merely in accepting orders for which a vertex distance is required. That is any prescription for spectacles where at least one lens has a power ≥+/-5.00D in the highest principal meridian, including the reading addition where appropriate.

Eye care practitioners should bear in mind the need to include BVD on the prescription, even in such seemingly low prescriptions as, for example, +1.75/+1.75 x 180 Add+1.50. In this case there is +5.00D in the highest meridian for reading. They might also consider, given the nature of modern tailor-made personalised lenses, that they should include a vertex distance on all prescriptions, so as not to limit the choice of patients at the time of their dispensing. The inclusion of a BVD on all prescriptions would also place an obligation on all unregistered sellers to verify any change to legally dispense the prescription, since the obligation is to check the vertex distance of the frame when a vertex distance is included on the prescription regardless, it would seem, of its power.

Date of Prescription

Section 27 of the Opticians Act 1989 regulates the sale of optical appliances by registered opticians. Since there is no legal requirement for a written sight test prescription within a two-year date, a registrant can dispense an out-of-date prescription or determine the prescription by neutralisation of an existing pair of spectacles using a focimeter.

It has also been contended, by a former Registrar of the General Optical Council no less,1 that the fact spectacles may be dispensed by a registrant without a valid sight test prescription may also permit a dispensing optician to conduct a refraction and supply spectacles, providing the result of the refraction cannot be construed to be as a result of a sight test as it is defined within the Act. This has clearly proved too great a hurdle for dispensing opticians who have now had over 32 years to think about such details; of greater concern to most dispensing opticians and optometrists, as well as corporate registrants, has been the vexed issue of supervision which will be turned to shortly.

Registrants have the ability to over-ride certain aspects of the 1984 Order if they feel it is in the patient’s best interests to do so. However, in general, a registered practitioner should hold themselves to at least the same standard as that of an unregistered seller and many would argue they should go above and beyond. For example, a registrant can choose to dispense a patient whose prescription has expired but must document the reasons for doing so and be sure it is in the patient’s best interests.

Case Study; Dispensing an Out-of-Date Rx

Some patients have a greater fear of visiting their eye care practice than visiting the dentist. Patients will be encountered who refuse to have non-contact tonometry and, very occasionally, patients who have a phobia of refraction may also be encountered.

One such case was MW, a bilateral aphakic female whose 20-year-old ophthalmologist’s spectacle prescription was of the order of +25.00DS Add +3.00 (R&L). Because of the time since the refraction had been undertaken, half a dozen local opticians had refused to dispense her with any spectacles.

Being satisfied that the patient may be phobic is not sufficient grounds for providing an optical appliance to an out-of-date Rx on its own. For consent to be valid, it is also necessary to ensure that the patient is aware of any potential risks they may be exposing themselves to, and also that the wider public will not be put at risk as a result of the practitioner agreeing to supply an out-of-date Rx.

In this case, it was possible to use a shop-floor Snellen chart, in conjunction with the old (broken and beyond repair) spectacles, to determine that the patient had reasonable functional distance vision and an excellent standard of near vision afforded by the obvious spectacle magnification. It was confirmed that the patient did not drive and would not, therefore, be putting others at risk. It was explained that having an eye examination checks the health of the eyes and that slow progressive conditions such as glaucoma may be successfully prevented and/or treated without sight loss if caught early enough. The patient understood this but was unmoved and signed a disclaimer to this effect.

Lenticular bifocals were rushed through in under a week and the patient was very satisfied with them. On collection, the advice to have an eye examination was reiterated (and recorded) and, a few weeks later, the patient booked in, also taking the advice that she should have more than one up-to-date pair of spectacles. Amazingly, there was no significant change in refraction and, thankfully, no pathology was found.

Supervision

Modern optical practice often relies upon unregistered staff for dispensing spectacles. However, it is important for registrants who work alongside unqualified staff to realise that, merely by being on the premises, they are responsible for any ophthalmic dispensing or other regulated activity that is carried out and are acting as supervisor unless they can show that there was another registrant on the premises and it was reasonable for them to assume that they were supervisor.

In sole practitioner practices, the situation is straightforward. In other smaller practices, the dispensing optician might take responsibility for shop floor activity, the optometrist for pre-screening and the contact lens practitioner for support staff conducting contact lens instruction. In large practices the situation becomes much more complex as illustrated by the next case study.

Case study; Who Is Responsible?

MD, age 42, attended a community eye care practice and presented a car park ticket voucher for a free sight test to a trainee dispensing optician. The trainee had only recently started their course and was covering the front desk at the time. Being so distracted, the trainee neglected to find out that the patient was entitled to a GOS sight test (claimable at the value of the private test £0.00) on the grounds of having a family history of glaucoma. Subsequently, with the help of ambulance chasing lawyers, somehow it was later claimed that MD had been ‘unduly put at risk’.

Who was the responsible registrant? The student? Her academic supervisor (who was on holiday at the time)? Her secondary academic supervisor (who was on their lunchbreak)? The dispensing optician (who was on the shop floor at the time)? The optometrist director (who was in the back office)? One of the several other registrants in practice that day or the optometrist who examined the patient?

In the event, it was shown that the practice had previously recorded a family history of glaucoma so the ambulance chasers backed off. However, had this case related to dispensing or another clinical activity such as repeat fields, and had a qualified registrant not actually seen the patient, the situation would not have been as clear-cut. Practices should have clear protocols to identify the responsible registrant, ideally linked to the diary system, and recorded for each regulated transaction or transaction that could result in potential liability.

Businesses, whether registered or not, become wholly responsible for any dispensing that is carried out when there is not an individual registrant on the premises. It is therefore incumbent upon all optical businesses to ensure either that a registrant is available at all times or ensure non-registered staff are fully aware that they must not dispense restricted categories of patient if there is no registrant ‘on the premises and in a position to intervene’.

Standards of Practice for optometrists and dispensing opticians, set out by the GOC in 2016, define expected standards of behaviour but allow each registrant to use professional judgement to determine how these standards are met. It is important to be very clear that ‘each registrant’ is accountable, as well as responsible, for any actions undertaken (and those not undertaken) irrespective of any directions issued by an employer or colleague. In simple terms, all decision-making must be justified in line with these standards of practice.

GOC Standard 9 requires that the supervising registrant has the relevant ability and experience in those tasks being supervised and only delegates these tasks to members of staff that have the appropriate skillset to carry out them out.

Clinical responsibility remains with the supervisor and the identity of a member of staff conducting delegated activities should be noted on the patient record.

This is of particular importance to those registrants who work in a locum capacity and may not have the knowledge regarding the capabilities of members of staff that they are expected to supervise. When starting any working day in a new practice, clarity is essential from the supervising registrant and all unregistered members of staff being supervised should be made aware of the level of supervision that the registrant will undertake. It is also important to offer a reminder of the restricted categories.

Ready-Made Reading Spectacles

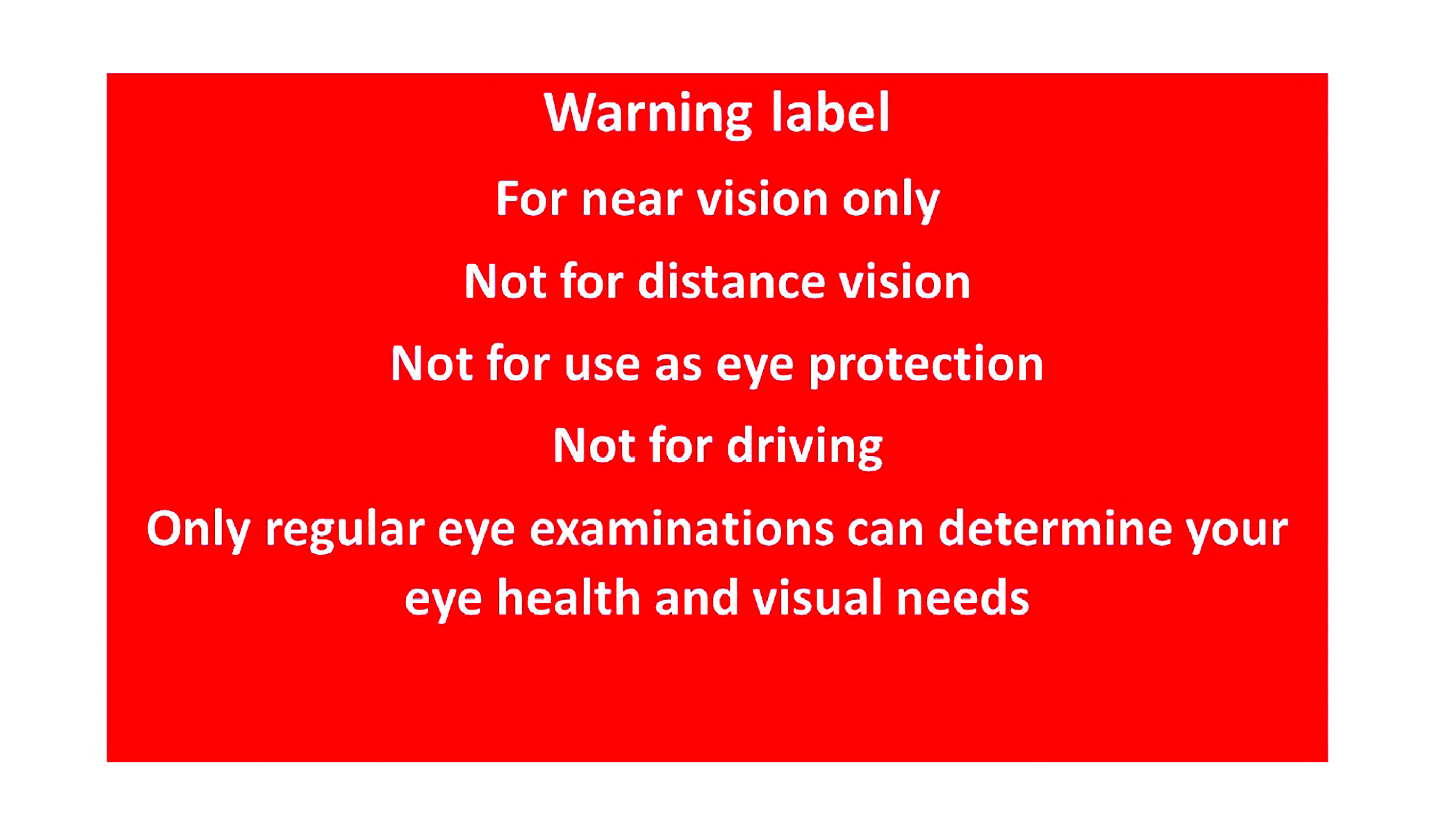

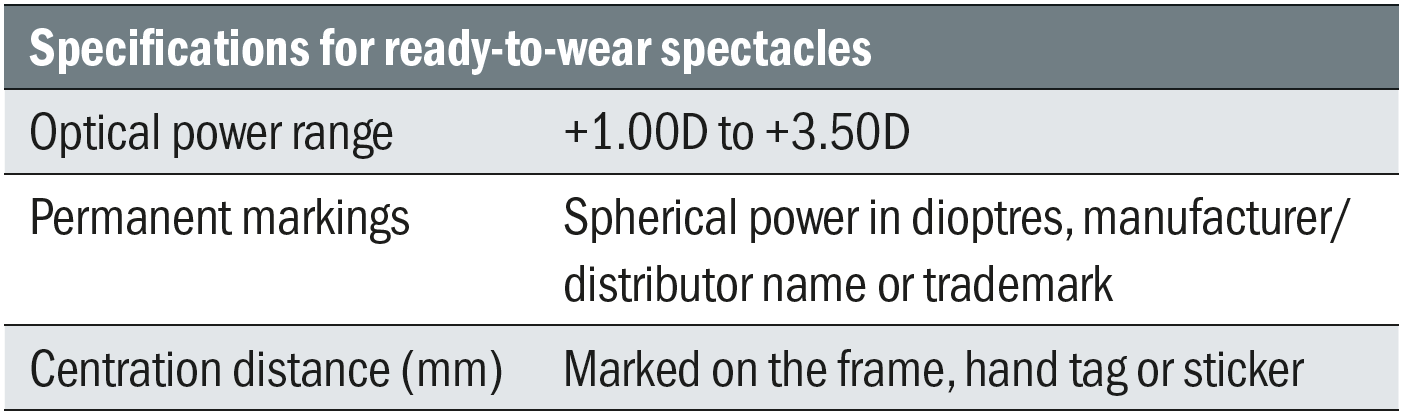

The sale of ready-made reading spectacles became legal following the introduction of the Sale of Optical Appliances Order of Council 1984 and then further clarified in the Opticians Act 1989 27(2). When supplying ready-made reading spectacles, registrants maintain a duty of care and should follow guidelines issued from the professional bodies ensuring that the appliance is suitable for the patient as stipulated in GOC standards 7.6 and in compliance with BS EN 14139:2010 (table 1). The regulations demand that patients are provided with information in the form of the warning label in figure 2.

Figure 2: Warning label used for ready-made reading spectacles

Figure 2: Warning label used for ready-made reading spectacles

Table 1: BS EN 14139:2010 standards

Table 1: BS EN 14139:2010 standards

Case Study; Preventing the Illegal Sale of Optical Appliances

The actions of our professional bodies in preventing illegal supply often go unnoticed. However, in the authors’ experience, a simple letter pointing out the legislation and regulations may be just as effective and far less costly than legal action. Individual email action by practitioners themselves can be highly effective, especially if they copy in their representative body (either ABDO or the AOP) and the General Optical Council. When multinational online retailers breach national laws, they seemingly do so unwittingly and are often happy, following their making obvious legal checks, to withdraw products from sale without fuss where they agree that the legal position is correct.

Also in the authors’ experience, individual action and that of professional and regulatory bodies has resulted in large retailers (including Amazon and Argos) withdrawing plano cosmetic contact lenses from sale. Similarly, the sale of adjustable focus distance vision spectacles has been curtailed considerably through the application of the 1984 regulations that state that lenses must be plus power and no more than +5.00DS. In these cases, the power range of -6.00 to +3.00DS is illegal.

The sale of ready-made varifocals and occupational lenses by supermarkets and bifocal sunglasses by pharmacies has also been successfully halted on the basis that part 3(1)(d)(iv) of the 1984 Order states that appliances are only exempted from Section 27(1) of the Opticians Act providing ‘no lens of which is bifocal or multifocal’.

It is worth noting that there are some seeming inconsistencies between the 1984 Order and the 1989 Act. The latter states that lenses for the relief of presbyopia should not exceed +4.00DS whereas the 1984 rules allow up to +5.00DS for ‘relieving a defect in near sight’. Additionally, exemption is provided for spectacles used temporarily for eye protection in sports which may, according to Section 27 (2)(b)(i), not exceed +/-8.00DS and are most familiarly seen in ready-made prescription swimming goggles.

What is an Optical Appliance?

The GOC recently clarified that the Opticians Act defines an optical appliance as ‘an appliance designed to correct, remedy or relieve a defect of sight,’ so does not cover products that simply ‘magnify’. Many low vision aids fall into this category, even though they are used by those with defective vision. Magnifiers of varying quality can be purchased quite legally from many retail establishments, such as garden centres, supermarkets and discount shops, as they are not considered to be an optical appliance. However, the guidance does make clear that spectacle mounted aids are a restricted category of appliance.

Similarly, plano cosmetic contact lenses are not considered an optical appliance, which is why they are specifically mentioned as ‘zero powered contact lenses’ throughout the regulations to ensure that the law on supply applies to them as intended.

Magnifiers are only considered to be an optical appliance if prescribed for an individual to correct a specific sight defect, for example spectacle mounted telescopes with a prescription element or custom-made centration (figure 3).

Figure 3: A bioptic telescope centred over a correction for astigmatism is considered to be an optical appliance. Many simple low vision aids are not

Figure 3: A bioptic telescope centred over a correction for astigmatism is considered to be an optical appliance. Many simple low vision aids are not

While the sale of magnifiers from places other than registered opticians provides a beneficial service, sadly they are often used by those patients that are in the greatest need of the protection and safety that the Opticians Act affords for any product deemed to be an ‘optical appliance’. Many low vision patients are not aware of the products, services and expert advice that eye care practitioners could provide. Just as sadly, this is at least partly because most eye care practices do not engage with low vision patients in any meaningful way.

Consent

When supplying spectacles, GOC standard 3 requires registrants to obtain valid and informed consent. This applies to the supply of optical appliances as much as it does to more invasive procedures, such as contact lens fitting, lid eversion or applanation tonometry. Registrants’ responsibilities are such that, when supplying any optical appliance, examination or treatment, patients must be given all options that are appropriate and the risks and benefits of each explained so that an informed choice can be made.2

Case Study; Informed Consent

In one well-known case, a longstanding contact lens patient was seen by a locum instead of his usual contact lens practitioner. The locum informed the patient of more modern lenses that would offer the benefit of increased oxygen transmission and the possibility of longer, more comfortable wearing times. The patient accepted the offer to upgrade.

At a subsequent check-up with his usual practitioner, the patient (a medical negligence lawyer) asked how long his new lenses had been on the market and was disappointed to discover that they had been introduced over a decade earlier. A defensive attitude and poor communication no doubt precipitated the complaint to the General Optical Council who found against the practitioner for failing to recommend better contact lenses to a patient who had worn standard lenses for over 10 years and would have benefited from more oxygen and longer healthier wearing times had they been previously been offered an upgrade to silicone hydrogel contact lenses.

Although the sanction, a warning, was not excessively punitive, the contact lens practitioner had the case hanging over him for many stressful months and lost several days practice income as a result of preparing his defence and attending hearings.

Informed consent is becoming a hotly debated issue.2 Do registrants have a duty, for example, to discuss laser refractive surgery or clear lens extraction, or only services that they can reasonably provide themselves?

A newer hot topic is myopia management. The year 2021 has seen many new ophthalmic and contact lens products come to market for the management of myopia, with more expected to be launched as face-to-face conferences and exhibitions resume following the successful rollout of Covid-19 vaccines. The requirement to obtain valid consent means it is essential for optometrists and dispensing opticians to inform prospective patients of their myopia management options. By not doing, so GOC standard 3 and 5.3 are not met and practitioners could find themselves subject to fitness to practice proceedings.

Conclusion

Despite the age of the laws and regulations, in many respects they remain broadly fit for purpose. However, they have not adapted to the internet age or the plethora of high-tech optical solutions that are now available to patients and practitioners alike.

The Opticians Act and GOC Orders will never win a ‘plain English’ award and can be difficult to interpret. Hopefully, the long-anticipated new regulations will correct this. Fortunately, professional bodies such as ABDO, the AOP, the College of Optometrists and FODO, as well as the GOC itself, work hard to translate the law into practical advice and guidance.

In essence, the law represents the bare minimum standard that is expected, whereas professional body guidance is generally seen as best practice and is often relied upon in fitness to practice cases. In daily practice, it is each practitioner’s responsibility to be conversant with how to access this guidance and seek clarification if unclear about any course of action. In addition to professional indemnity insurance (a legal requirement for registration), being a member of a professional body may bring with it access to free legal advice and, if a case is brought against a registrant, legal representation.

This article only scratches the surface of the Opticians Act and GOC regulations as they apply to ophthalmic dispensing. Legal and regulatory aspects will be considered further in future articles relating to paediatric and special needs dispensing, low vision, and the supply of contact lenses. It is incumbent up all registrants to know the law and ensure that those they supervise do not cause them to fall foul of it.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO is senior lecturer in ophthalmic dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians.

- Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CET provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College.

Further Reading

- The Opticians Act 1989; https://www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/opticians_act.cfm

- Sale of optical appliances order of council 1984; https://www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/rules_and_regulations.cfm

- Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians and further guidance on consent; https://standards.optical.org

References

- Wilshin R. The law in practice. Optician, 28.04.2005

- Hirji N. Navigating informed consent. Optician, 15.05.2020