In the last article in this series (Optician 14.05.21), I discussed e-readers and some simple apps that allow existing text to be presented in a way that would help someone with sight loss to read it more easily. In this article, I will continue this theme by focusing on a number of apps (some paid for, some requiring subscription, but many free) which I have some experience with and have found to be of help to some of my patients.

There has been such a rapid growth in the numbers of apps for the visually impaired that it is almost impossible to keep up to date. Many of the most useful apps presented here have been recommended to me by patients themselves, while others I have discovered for myself when trying to help a patient with a very specific need, as illustrated by the following case.

Case

A 64-year-old woman attended the low vision clinic whose main problem that she could no longer read her Bible, something that was very important for her. She described how the book had tiny print and very thin pages and it was difficult for her to manage even with magnifiers. As is so often the case, she had not brought the book with her.

“Important point; when booking appointments, always

remind patients to bring as many examples of materials they

find difficult to see with them to your clinic.”

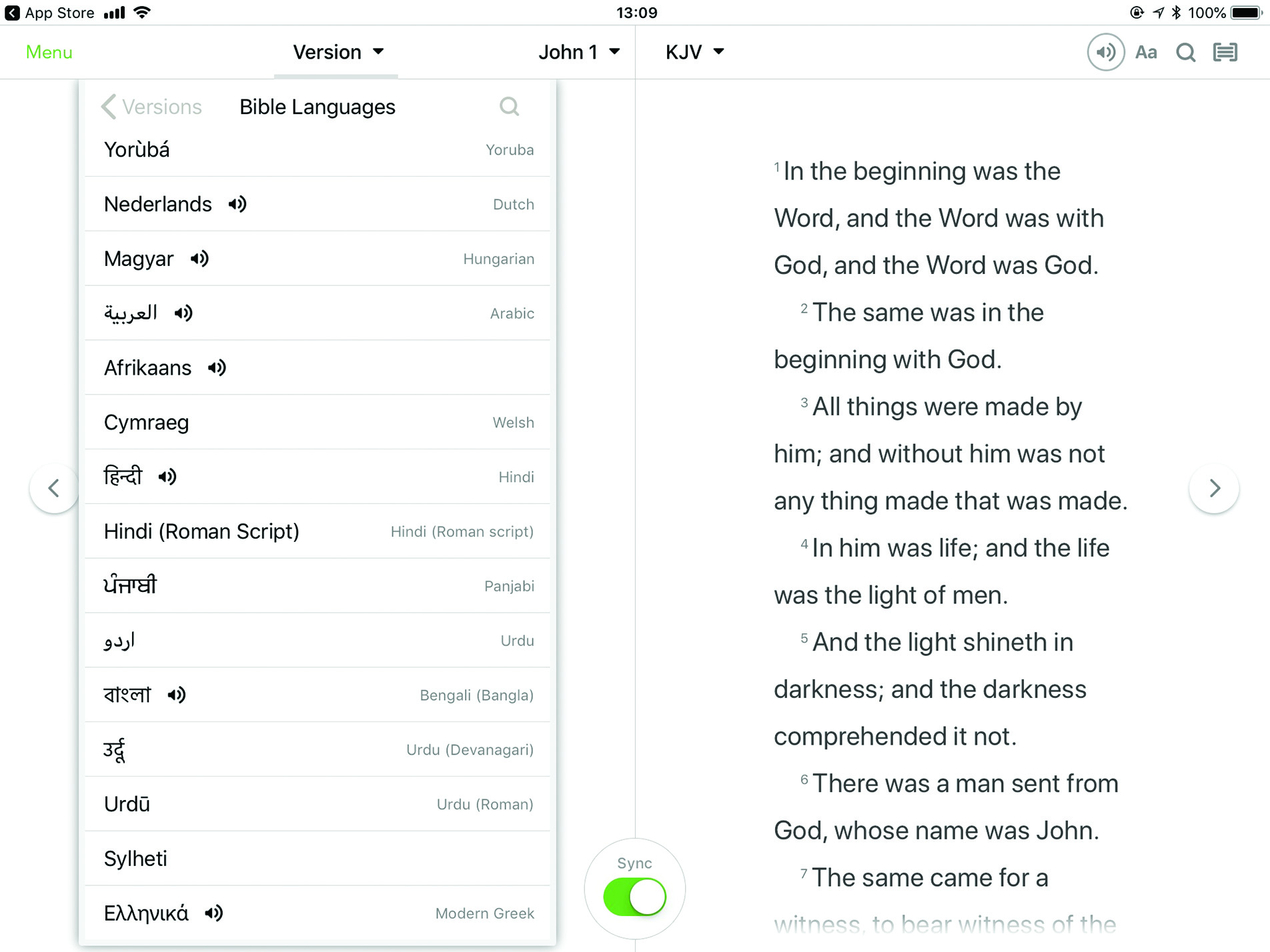

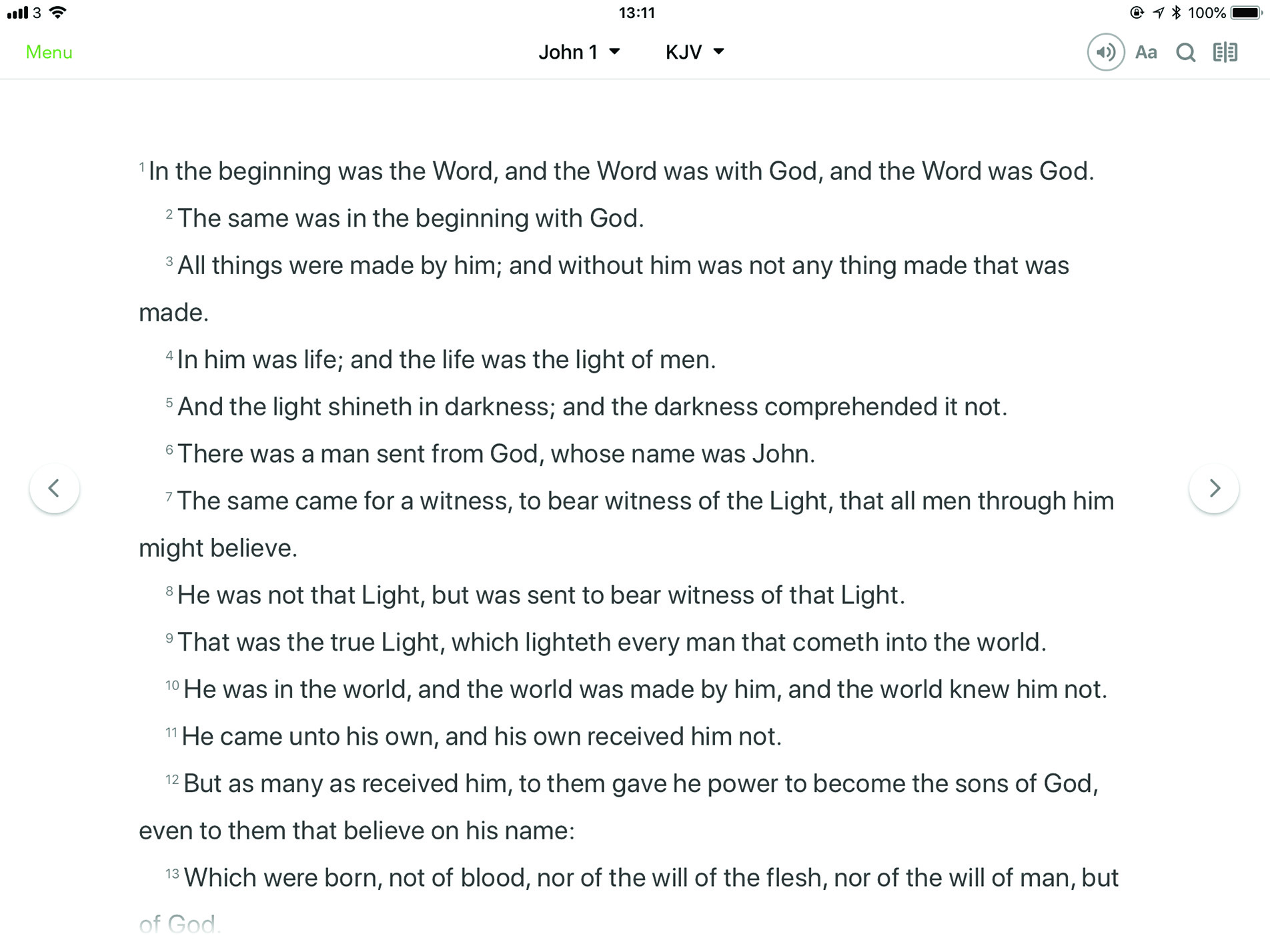

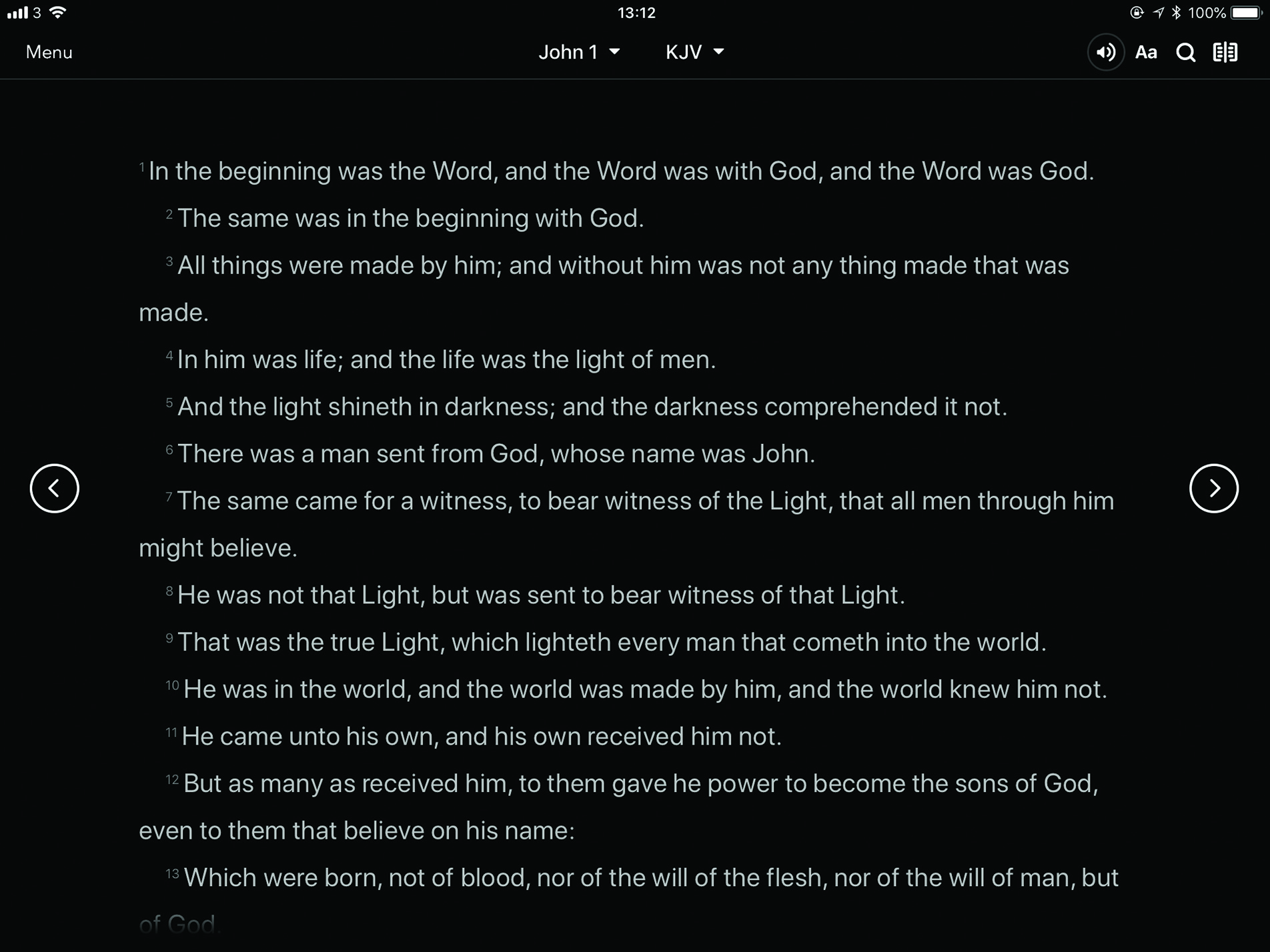

The patient was originally from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and spoke some French, a little English, but her preferred spoken tongue was the Congolese dialect of Lingala. I first went to the free app named ‘Bible’ (figure 1) which offers various versions of the Bible in over 40 languages (figure 2), which can be read in a range of themes and formats, including standard black on white (figure 3) and reverse contrast (figure 4), and can be enlarged as required (figure 5).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 5

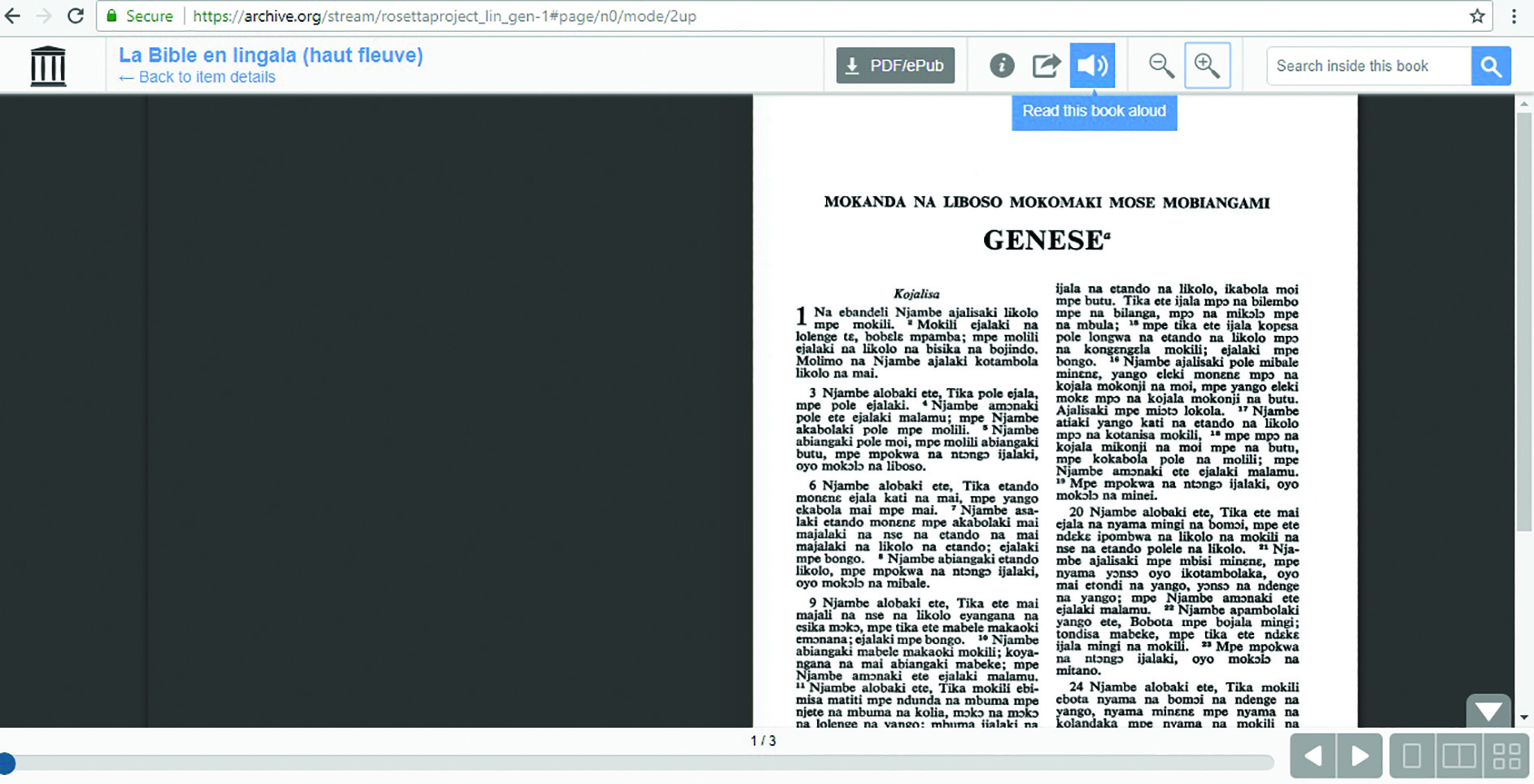

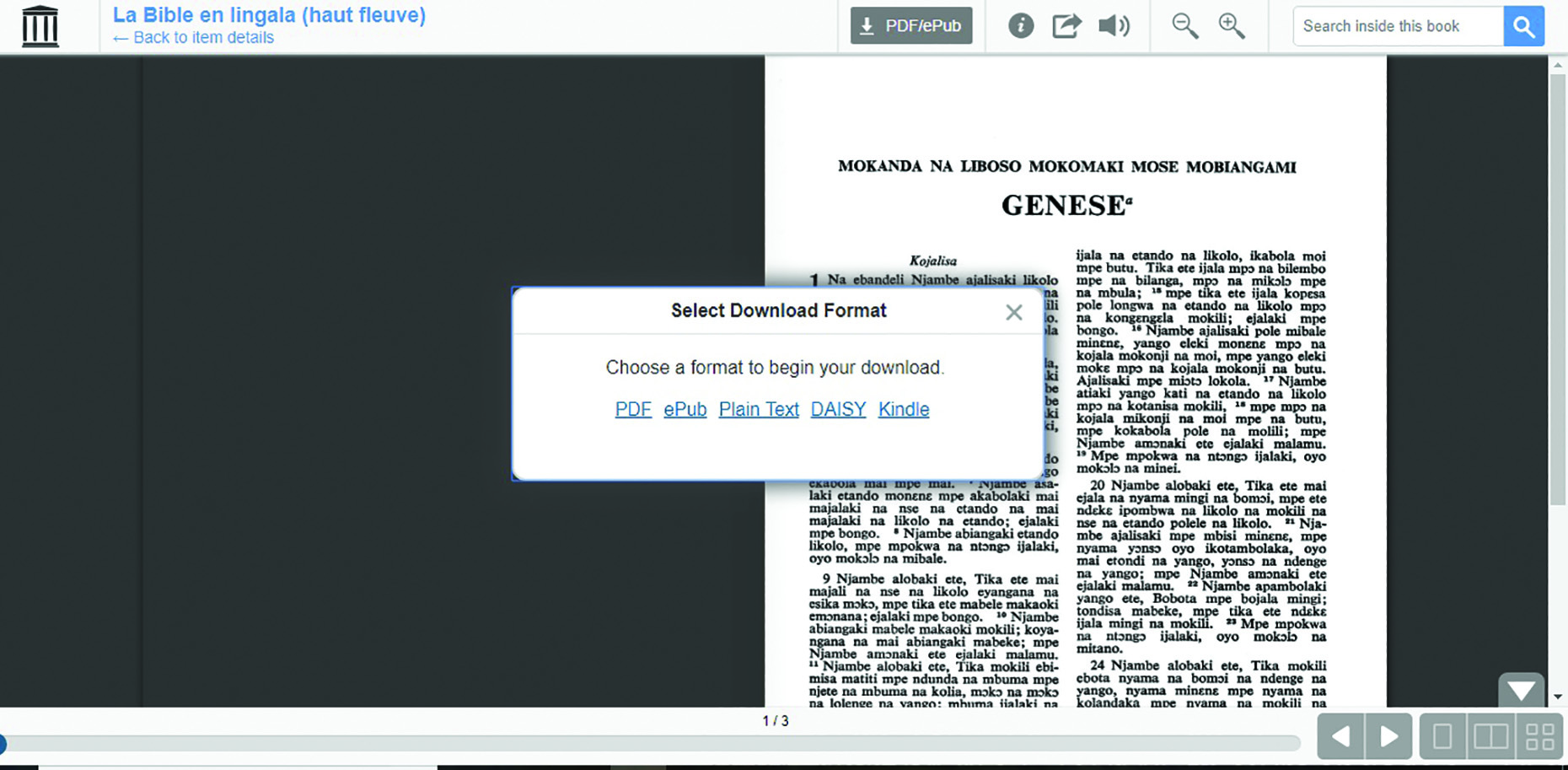

A Lingala version was not available so I went to the excellent Rosetta project site (https://archive.org/details/rosettaproject), searched for ‘Lingala Bible,’ and immediately found what I needed (figure 6). The text could be read on screen, in an enlarged form to meet needs, read out loud by an audio option (though the automated voice was a turn off for the patient) or downloaded to any preferred reading software (figure 7), such as Kindle or DAISY (see later). As the patient preferred tangible printed pages to digital screens, I created a file of the appropriate size and contrast which a family member of the patient was then able to print off within about 20 minutes at home. Problem solved.

Figure 6

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 7

I mention this case because, increasingly, visually impaired patients are able to access options online or via downloaded apps that are a great help to them, in many cases more so than the simpler magnifiers we have traditionally supplied. As eye care practitioners, it seems important to me that we are aware of the sorts of help that might be available and are able to keep up to date with what is out there. None of these apps should ever replace the advice and help offered by ECPs and allied professionals, such as ECLOs and rehabilitation officers, but I believe we should embrace them and be able to guide our patients towards their successful use.

This article will look at a few useful apps that might prove useful to your visually impaired patients which I have tried to categorise according to their main functions.

With an estimated 200,000 health and medical apps available on iTunes and Google Play, many with a focus on eyes and vision, and an estimated 500 new medical apps appearing on a weekly basis, such a review is never going to be comprehensive. That said, there are some useful and regularly updated resources worth knowing about which are listed at the end of the article.

Object recognition

Be My Eyes (iOS and Android)

The Be My Eyes app offers valuable support to all with a visual impairment and is certainly worth being aware of. In effect, the app allows a global community of sighted volunteers to act as a pair of eyes for someone with reduced vision on demand via a live video call.

When first opening the app, you are asked whether you are visually impaired and wishing to use the service, or a sighted volunteer able to offer your service. I registered a while ago as a volunteer and, after answering a few simple questions, was then taken through an explanatory video showing the sort of task you may have to help with. The example I worked through dealt with a live feed from the smartphone camera of a woman wishing to wear a red jumper but who could not tell it apart from others (figure 8). I was able to tell her when she was holding the red one.

Figure 8

Figure 8

Since then, every now and then, a prompt appears on my screen (figure 9) when a sight impaired user has a problem that might be solved by a second pair of eyes.

Figure 9

Figure 9

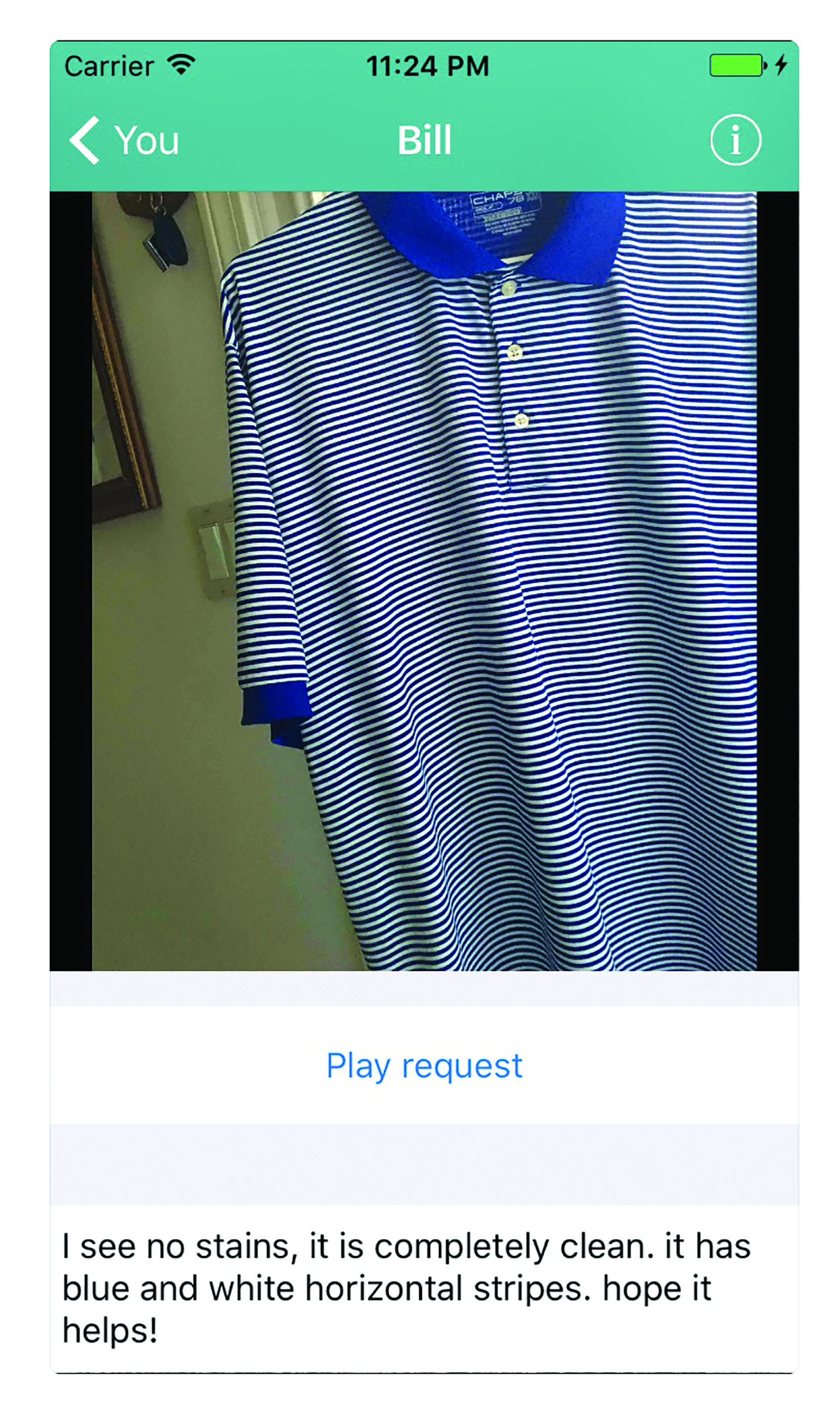

BeSpecular (iOS and Android)

The BeSpecular app is another free app that allows a visually impaired person to take a photo of what he or she needs help with and attaches a voice message, which is sent to a community of volunteers (or ‘sightlings’ as they call them). Those sighted who are available can reply to the visually impaired person via the BeSpecular app with a voice or text message. Usually within just a few minutes, the user receives a reply (figure 10) and then, Uber-style, rates the helpfulness of the volunteer out of five stars. This app is popular ‘because you get a description from a real human being, it’s very accessible and it’s quick.’

Figure 10

Figure 10

TapTapSee (iOS and Android)

TapTapSee is a mobile camera application designed specifically for blind and visually impaired users powered by the CloudSight Image Recognition API which accesses an extensive image library to identify most objects accurately. The app utilises the device’s camera and VoiceOver (iOS) or TalkBack (Android) functions to photograph objects and identify them out loud for the user.

In TapTapSee, the user double-taps the device’s screen to photograph any two or three-dimensional object at any angle, and have it accurately analysed and identify within seconds. The device then both describes the object audibly to the user as well as showing a text description on screen.

I tried it out first on my coffee mug. I pointed the camera at the mug and tapped the screen to capture the image. Within seconds, the description correctly appeared onscreen. I find many patients prefer to use the app with headphones attached when in a public space.

Aipoly Vision (iOS and Android)

As the name suggests, this app employs artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to offer both object and colour recognition and is aimed at both the visually impaired and the colour blind. Once the app is open, you simply fill the onscreen camera frame with the object of interest and then select any of the buttons at the bottom of the screen to announce the object’s identity (figure 11), colour and a range of other options. Note, some of the functions require a small subscription.

Figure 11

Figure 11

Generally, this works well, though it can make mistakes; my cat Saski is quite often claimed to be a dog.

Color ID (Android) Color Inspector (iOS)

There are many colour identification apps available that accurately announce the colour of a target under view. They link the inbuilt camera of a device with a voice to announce the colour of any object being pointed at. The apps even claim to settle any colour constancy dispute, as with the famous stripy dress photo that went viral some time ago. I tried both the Android app (figure 12) and the iOS app (figure 13) on my dart board and both seemed to work well.

Figure 12

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 13

iDentifi (iOS)

This app for iPhones and iPads uses artificial intelligence to enable a visually impaired user to click a photo and get an instant description. It is able to recognise objects, brands (figure 14), colours, facial expressions, handwriting and text, with a good degree of accuracy and delivers an audible description of the image’s contents to the user. In fact, it is obligatory to activate the Voiceover option before using the app. The interface is very accessible and gives the option to choose from a range of object and text recognition selections and to specify how fast you want the app to speak.

Figure 14

Figure 14

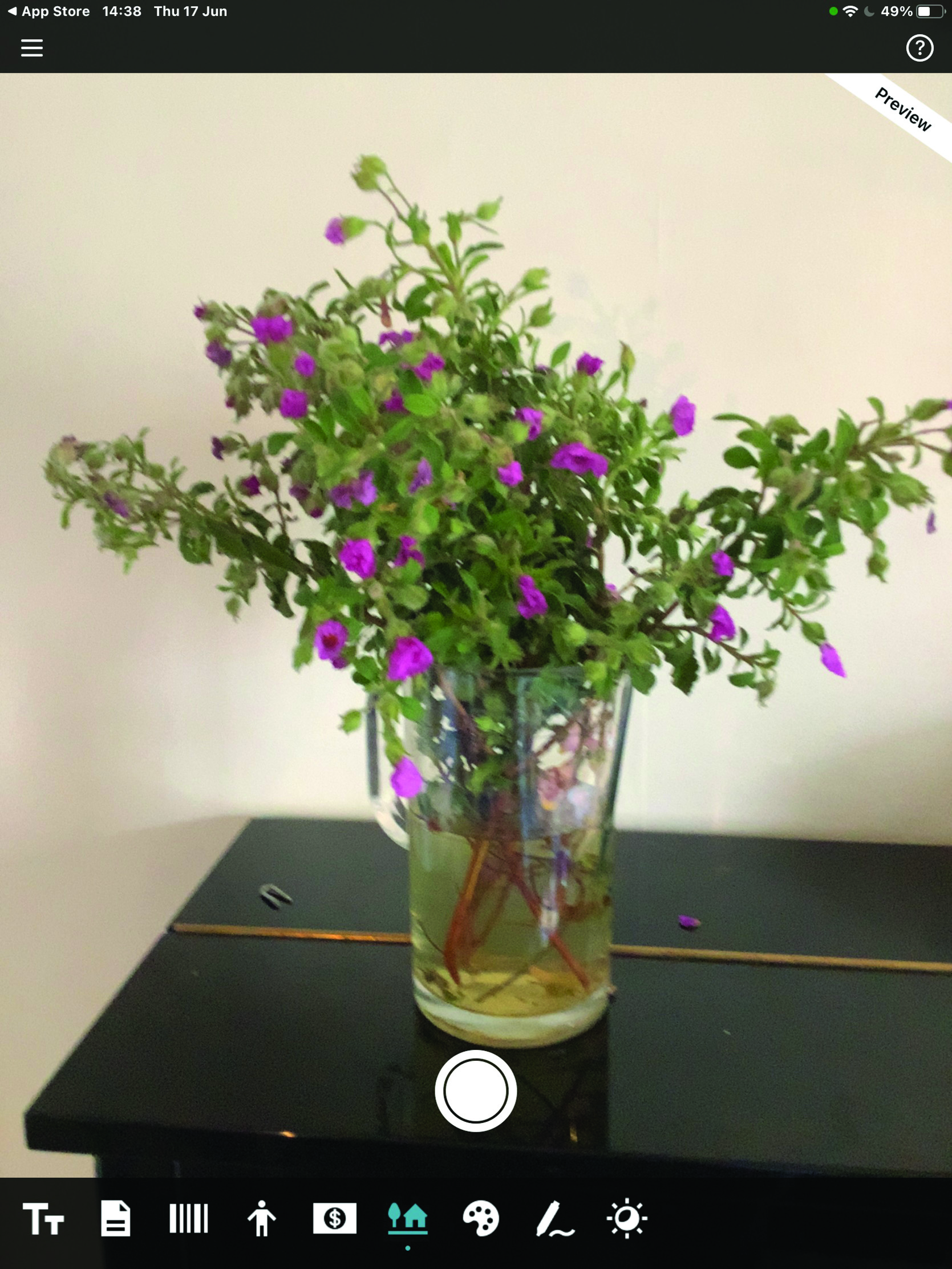

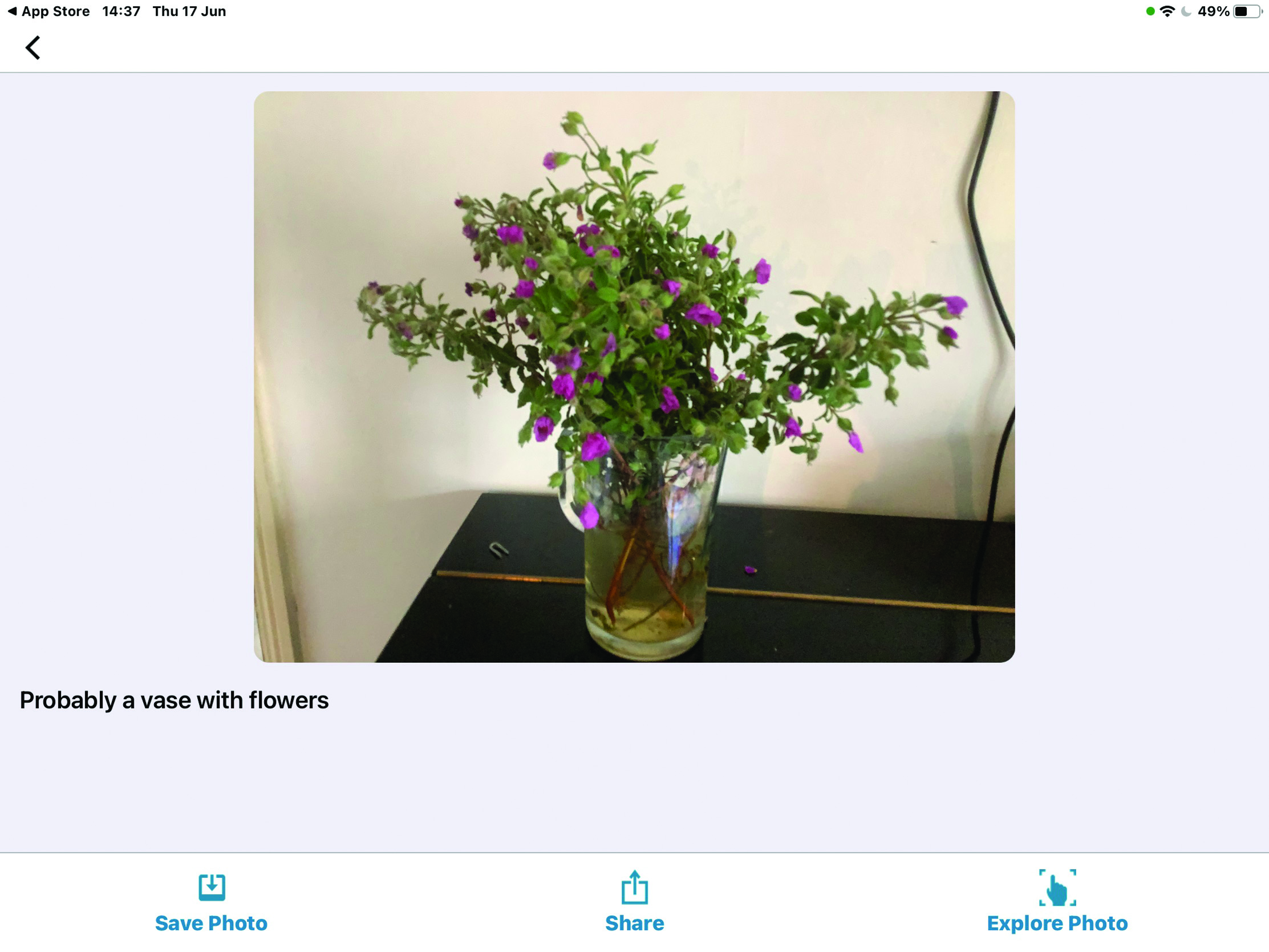

Seeing AI (iOS)

As this comprehensive app tells you itself when you first launch it, Seeing AI is ‘a free app that narrates the world around you.’ Designed for the low vision community, this research project harnesses the power of AI to describe people, text and objects.’

By pointing the smartphone or tablet camera at the desired object, a number of options appear on the screen (figure 15). These allow a wide range of image interpretations, whether it be text reading (either in tiny snatches or full pages at a time), facial recognition, or in my simple case, the identification of a vase of flowers (figure 16). The app can read bar codes, identify product names, read nutrition labelling, cooking and other instructions; the list goes on.

Figure 15

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 16

Using Seeing AI, you can snap pictures of your friends and family members, and later use the app to tell you who’s nearby. An experimental setting can describe the scene around you, such as ‘a fenced-in garden’ or ‘a blue door on a house.’ You can also import images you receive in email, or find on Facebook or Twitter, and the app attempts to describe the action and read any text contained in the image.

A recent update to the app includes several new features:

- A currency reader that, as yet, can only tell you the denomination of US and Canadian currency. All you need to do is select the ‘currency’ option and point your iPhone’s camera at the bill.

- A light indicator that changes audible tones as the light level increases. Perfect for locating windows or determining if you’ve left the lights on—again.

- A colour monitor that can name the colour of clothing and other items you hold in front of the camera.

- A handwriting recogniser that can actually read handwritten script reasonably well. The performance will doubtless improve over time.

I strongly recommend you have a look at this technology which, remarkably, is free.

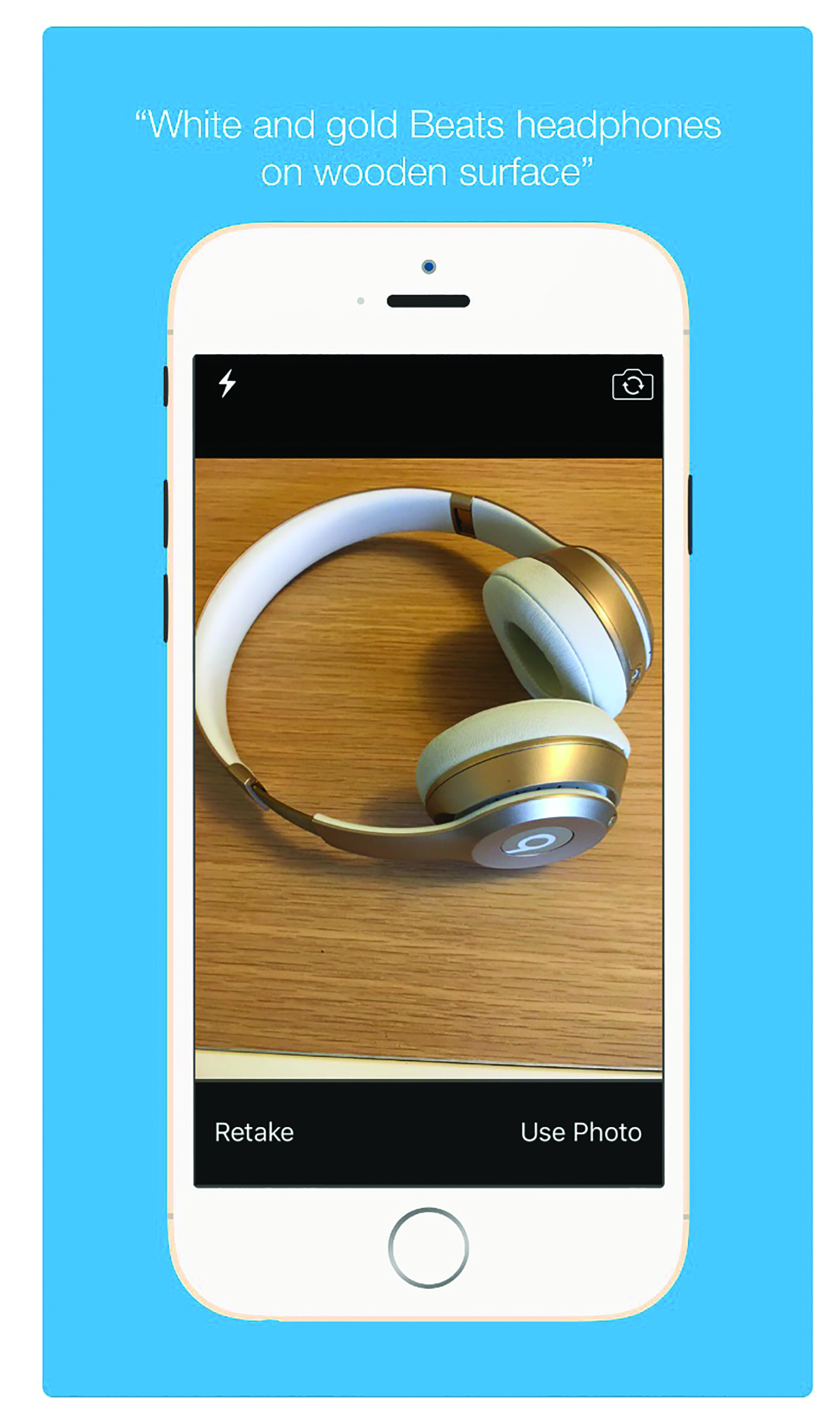

Camfind (iOS and Android)

This is another free picture identification app for a smartphone or tablet but instead relies on uploading the image onto the web where identification is made and reported back to the user from algorithmic processing and without the need to interact with a sighted person. I took a photo of an apple and instantly received a correct identification along with an unexpected amount of further information about fruit and healthy eating (figure 17).

Figure 17

Figure 17

ViaOpta Apps (iOS and Android)

Novartis has produced a number of interesting apps that are aimed at recognising objects, surroundings and faces. At the time of writing, the ViaOpta Daily worked well for object recognition (figure 18), the ViaOpta Nav was excellent as a navigation aid, but I could not easily locate the face recognition app ViaOpta Hello, which currently seems to be downloadable only via a PC which was less than helpful.

Figure 18

Figure 18

Money Readers (iOS and Android)

There are many useful apps able to correctly identify money of different denominations and currencies, some also offering options to count stacks of notes. I found some of these less than reliable, and many have in-app purchase requirements. The Cash Reader app (iOS) is aimed at the visually impaired and I found it worked every time (figure 19), though for foreign currencies or very large denominations (sadly not a problem for me) extra charges need paying.

Figure 19

Digit-Eyes (iOS)

The Digit-Eyes apps allow a smartphone to be used as a bar code scanner. The Lite version will read QR codes while the full version, for reading all bar codes, costs a tenner. More than just a price scan, the app reads out a whole range of information about any coded product, including nutritional information, and also allows the user to print labels to help them with future

recognition.

Navigation

Light Detectors

These clever smartphone apps are able to represent incident light as a sound signal; the greater the light intensity, the higher the pitch of the tone. Using this allows a visually impaired person to find where a window is, where their lamp is positioned in a room, or simply to help decide if the curtains are drawn. Perhaps best used with headphones, the app I found easiest, the free Boop Light Detector, also gave a vibrate option.

NaviLens (Android, iOS)

NaviLens is an app that makes it easier for visual impaired people to access information through specially designed colour QR codes (figure 20) that are available for users to download for their own personal use. Until now, these tags were only available in public spaces such as train stations. In this new functionality, the codes provided are blank for users to record any information about the objects in their environment. The developers have created tags of different sizes that can be adjusted to the needs of remote reading. In addition, they are printable and easily separated.

Figure 20

Figure 20

Travelear (iOS)

This unusual app allows the user to select locations from around the world and then listen to a soundscape as if you were there. For the UK, I can only find ‘London Tube ride,’ something I am happier forgetting. However, the app can be used for promoting calm and wellbeing if used sensibly.

Envision AI (iOS and Android)

This is a smartphone app that describes the visual world around the user, while also offering text reading functionality. Works well (figure 21), but requires a fee after a 14-day free trial. I was interested to see that there are smartglasses available that can be paired with the app to allow the user to navigate their surroundings without having to hold up their smartphone all the time.

Figure 21

Figure 21

Soundscape (iOS)

This app, developed by Microsoft, is for iPhone only. Microsoft Soundscape enables people, particularly those with sight loss, to be better aware of their surroundings and so build confidence with their navigation and mobility. Unlike step-by-step navigation apps, which give direction instructions, Soundscape uses 3D audio cues based on local ambient sounds and helps the user to better immerse themselves within their local environment. Worth a look.

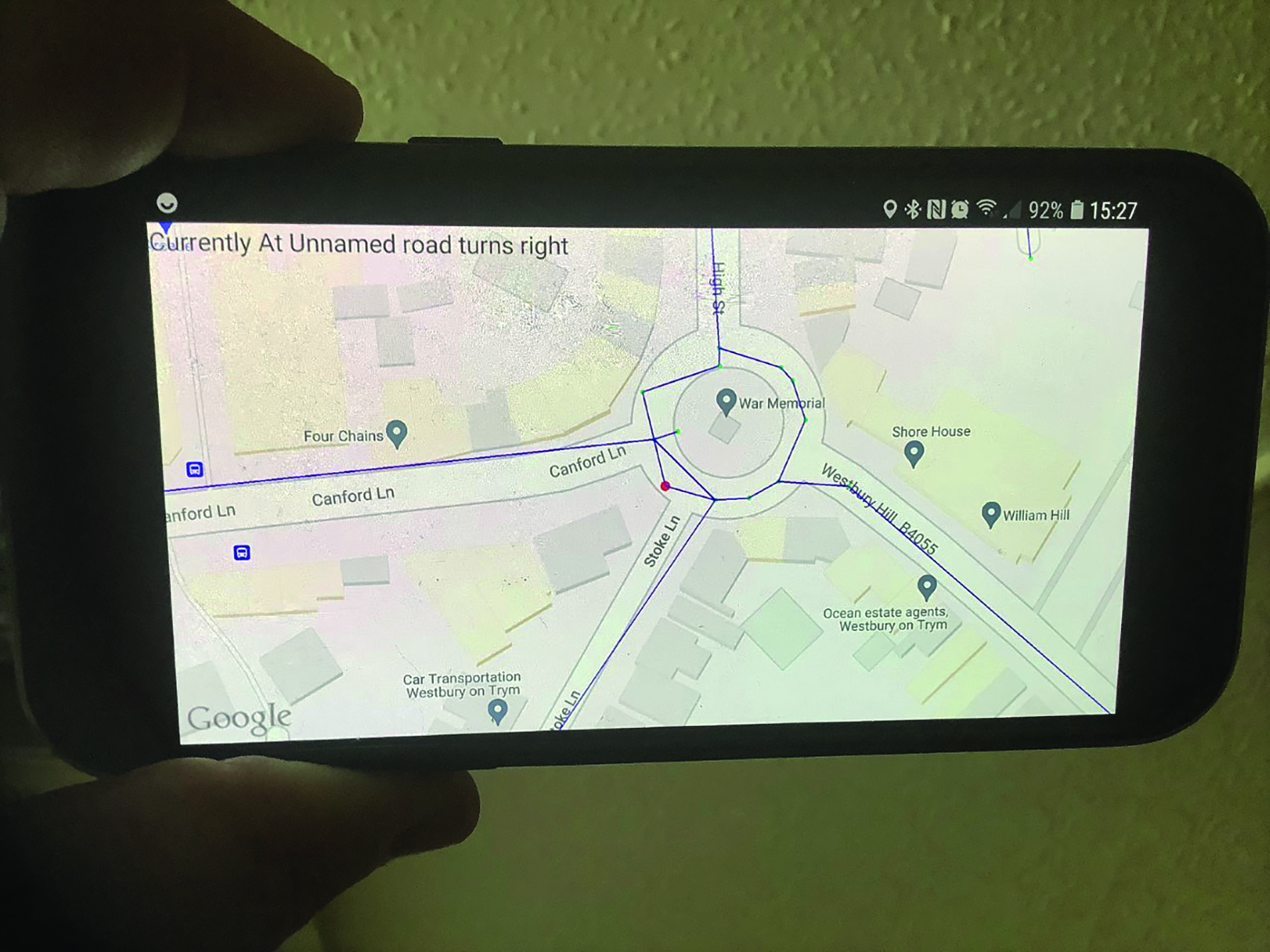

Intersection Explorer (Android)

Intersection Explorer is a more traditional navigational tool than Soundscape and speaks out the layout of the streets and junctions on a map as the user touches and drags their finger around it (figure 22). The stated aim is to help blind and low vision users get an understanding of an area both before venturing out and while on the go.

Figure 22

Figure 22

BlindSquare (iOS)

The BlindSquare app (cost £38.99) is a GPS system that locates a user’s position and then audio describes points of interest nearby. The user can change the radius of coverage area and then use their voice to request something specific, such as ‘where is the nearest library?’ By hooking up the program to an existing mapping system, such as Applemaps, the user will then have audio explanation of how to get to their point of interest.

Lazarillo-Accessible GPS (iOS and Android)

This impressive app uses locational data to describe the user’s location and then read out nearby places of interest on request, such as ATMs, shops and pubs. I found it to work very well and it is free.

Lazzus: GPS for the blind (iOS and Android)

Lazzus is designed for blind and visual impaired people and states the locality of the user, including street and number, nearby places of interest and favourites from previous use. It is only free for a limited trial period and then a subscription is needed.

Station Alert UK (iOS)

Many sighted people often miss their stop, let alone those with a visual impairment. The Station Alert UK free app allows the user to select your stations and save them as favourites. It will then alert them at whatever distance from the station has been selected, so they can sit back and relax.

ATM Finder (iOS and Android)

One of several apps aimed at helping to locate cash machines, the ATM Finder was developed in liaison with the Thomas Pocklington Trust. It uses GPS technology and can be adapted to specify machines as appropriate, such as those for a particular bank or ones with wheelchair access

Help with text

DAISY Talk (iOS)

Costing £39.99, the DAISY (Digital Accessible Information System) is an international standard for digital books designed for people with printed text disabilities. DAISY Talk is an app that reads out text of a DAISY book using the synthesised voice incorporated into an iOS device, though it is possible to convert files for Android device use. This app is very accessible but there are a number of other apps that will do the same job (such as Read2Go priced at £19.99, which reads aloud titles downloaded from Bookshare).

KNFB Reader

Whereas Seeing AI works well for iOS users, Android users will find that the KNFB-Reader is a must-have app for the reliable reading out of mail, general text and even handwritten text. It requires purchase of a licence to use fully (after a limited free period). The app uses the camera and voice settings to take a photo of text and then read it aloud in clear synthetic speech. It has text detection, so you know you have the printed side of the page. It also has tilt assist and viewfinder assist, helping you to get the whole page photographed. It can read letters, receipts, bills, menus or any other text and it does so instantly.

Prizmo 5; Pro Scanner + OCR (iOS)

Prizmo is a photo-based app that allows users to scan documents to PDF using advanced text-to-speech features. Prizmo utilises optical character recognition and is available in 23 languages, but most functionality beyond PDF scanning requires a payment.

Cinema

Greta (iOS and Android)

Greta is an app that enables people with sight loss to experience fully accessible cinema. It also includes foreign language subtitles and audio versions for an international audience. The app plays downloaded and existing audio descriptions through the headphones of the linked smartphone device. It can also be adapted for those with hearing impairment to display subtitles.

Final word

As stated at the start, this is only a snapshot of some of the many and varied applications that might prove useful to your patient. I do not think it likely we can always know everything available, but knowing a few is always useful.

The following links are an excellent way to keep up with the ever-changing available apps available for those with sight loss and visual impairment:

- www.inclusiveandroid.com/term/31/lists – a directory of android apps

- www.applevis.com – useful information about setting up an Apple device and also links to available Apple device-friendly apps

There are also a couple of useful current podcast resources patients might wish to subscribe to:

- Blindness podcasts – available at https://player.fm/podcasts/blindness – a wealth of useful broadcasts, ranging from the historical to those based on personal experience

- iSee – available to subscribe from the Apple podcast store

Also, the RNIB can be trusted for regular updates. For regular podcasts on the latest apps to be aware of, and including some opinion as to their usefulness, go to www.rnib.org.uk and type into the search field ‘assistant-apps’.