It is rare that the wrong pair of spectacles, or the failure to wear spectacles when required, can put a patient’s sight at risk. However, this is undoubtedly the case with children. Understanding the developmental stages of the visual system as well as the anatomical structures of the face, skull and ears is of greater importance for children as poorly fitted spectacles can compromise visual potential and lead to developing structures upon which a spectacle frame rests being permanently damaged.1 It is for this reason that ophthalmic dispensing to children under the age of 16 is restricted by law in almost all countries, with many countries providing additional safeguards for children under eight due to the plastic nature of the visual system while it is still undergoing development.

As discussed previously, (Optician 11.06.2021) paediatric dispensing falls within a restricted category in the UK and is regulated under the Opticians Act (1989). It can only be carried out by or under the supervision of registered optometrists and dispensing opticians.

Supervision

Within General Optical Council (GOC) Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians 20162 Standard 9 registrants are required to ‘ensure that supervision is undertaken appropriately and complies with the law’ and does not differentiate between the supervision of trainee optometrists, trainee dispensing opticians or unregistered colleagues undertaking delegated activities. It also does not differentiate between paediatric dispensing and other restricted functions such as the testing of sight or the fitting of contact lenses. When delegating restricted functions such as paediatric dispensing, pre-screening or contact lens instruction the same responsibilities apply.

The responsibility to ensure that supervision does not compromise patient care and safety is shared between the supervisor and those being supervised. All qualified registrants can supervise dispensing by unqualified staff, providing they deem themselves competent to do so, however, for dispensing episodes to count towards the academic requirements of trainee dispensing opticians and pre-reg optometrists, additional requirements must be met including the pre-appointed named supervisor(s) having two years recent relevant practical experience and a minimum of two years continuous qualified GOC registration leading up to the commencement of supervision.

To be compliant with the law, supervision must be ‘adequate’. Adequacy requires registrants to be sufficiently qualified and experienced to undertake the functions they are supervising and only delegate to those who have appropriate qualifications, knowledge or skills to perform the delegated activity.

Supervising registrants must also be ‘on the premises, in a position to oversee the work undertaken and ready to intervene if necessary, in order to protect patients.’ The law relating to this was clarified through legal precedent following the fitness to practice case GOC v Boots Opticians, Richard Simmons and Trevor Burgess 2009,3 where it was held that a trainee dispensing optician on the Isle of Man was not subject to adequate supervision when the registered supervisor worked on the UK mainland. This case revolved around an initial complaint that a child was given the wrong spectacles and the business registrant claimed the locum optometrist on the day in question had supervised, and was therefore liable for, the restricted transaction. The locum was able to defend themself as they claimed that they believed the trainee to be qualified and had not been made aware that the situation was otherwise.

Since the Isle of Man case, most eye care providers, opticians and a good number of independents have been subject to investigation and/or fitness to practice proceedings relating to supervision. Unfortunately, it is difficult to draw conclusions from these cases as the GOC no longer publishes transcripts of fitness to practice cases and many warnings are private in nature.

To some extent these cases have been less than helpful in clarifying issues surrounding supervision. For example, in an effort to demonstrate insight into their failings and show remorse registered corporate bodies offer up new standard operating procedures to the GOC. This has led to every company having different standard operating procedures and serves to confuse individual registrants especially new staff or those engaged on a temporary or locum basis. Some companies insist a qualified registrant checks every dispense for a child, sight impaired adult, complex prescription over +/-10.00DS and safety spectacles when the latter two categories are not restricted in law except for the provisions of the 1984 Order relating to sale of optical appliances by unregistered sellers (requiring among other things that the frame vertex distance be checked and the prescription recalculated for any significant change).

Case study – issuing the wrong spectacles

Perhaps the easiest mistake to make in practice is to issue a minus lens when a plus lens is required or vice-versa – the 2009 Isle of Man case was due to this sort of error and resulted in the business registrant being fined £30,000. In the authors’ experience young children, especially those getting spectacles for the first time, are unlikely to complain even if the error in prescription is comparatively very large. Such a case involved a pre-school child with a hospital prescription approximately:

R. +4.00 / -3.00 x 45

L. +4.00 / -3.00 x 135

who was supplied spectacles for the first time:

R. -4.00 / +3.00 x 135

L. -4.00 / +3.00 x 45

At some point, woeful transposition skills were evident and the spectacles were issued to the patient despite being checked against a correctly entered prescription. Transposing the prescription gives:

R. -1.00 / -3.00 x 45

L. -1.00 / -3.00 x 135

And this -5.00D overcorrection was not noticed until the patient attended their follow-up appointment at the hospital six months later, by which time the resulting over-accommodation had caused a convergent strabismus requiring prescribed prism that had to be gradually reduced, under the instruction of the ophthalmologist, over a period of over a year. The damage this adverse incident did to the reputation of the practice with the local ophthalmology and orthoptics clinics cannot be overestimated and went far beyond the financial cost of a dozen pairs of lenses.

When presented with scenarios of this nature CET audiences are incredulous that a child would not notice when a prescription was 5.00D ‘out’, however it needs to be remembered that a first time spectacle wearer knows no different and young children trust that the actions of adults are correct. It is worth considering the optics of what the child is likely to perceive. This child likely had reserves of accommodation of over 15 dioptres so could easily counteract the over-minus to see clearly even if convergence and diplopia was the result and caused one eye to be suppressed. The key to the apparent tolerance of the prescription was the full correction of the substantial oblique astigmatism present which, when combined with accommodation improved monocular visual acuity to best corrected levels far better than the uncorrected vision the patient had previously experienced.

It is good practice therefore to have a ‘welcome pack’ for locum practitioners outlining their terms of service and spelling out who they are responsible for supervising and the qualifications and/or level of competency they have achieved. It is then up to the locum to decide upon the level of intervention they require to make when supervising paediatric dispensing.

Given that the registrant must retain clinical responsibility for the patient – ‘when delegating you retain responsibility for the delegated task and for ensuring that it has been performed to the appropriate standard’ and that they must take all reasonable steps to prevent harm to patients arising from the actions of those being supervised, and comply with all legal requirements governing the activity, then how does a registrant decide what constitutes and appropriate level of intervention?

At the lowest level of oversight, as bare minimum, registrants should ensure their own details and the details of those being supervised or performing delegated activities are recorded on the patient record. At the opposite end of the spectrum oversight/intervention would involve being physically present when the task is carried out, coaching the supervisee throughout, and checking their work for accuracy.

This change in intervention level is seen clearly with pre-registration optometrists where they move from close supervision on day one to being left substantially to their own devices when they are deemed sufficiently competent to sit their final examinations. Clearly the level of supervision is dependent on the task, with pre-registration optometrists gradually being given a freer rein with regards to dispensing, refraction, contact lenses and eye health examination as their competence in each area reaches a sufficient standard.

The same is true for the supervision of a trainee dispensing optician or optical dispensing assistant carrying out a restricted function such as dispensing a child or sight-impaired adult, however, the way this is interpreted appears to vary considerably. Clearly when a colleague is new to dispensing children, they will need a much greater level of supervision and as they get more experienced, they will require less, but how much less?

Opinion is divided as to how paediatric dispensing should be supervised and there is also considerable confusion between what constitutes the law, which actions are not required by law but are standard operating procedures and company policies, and what constitutes best practice.

For example, the GOC requires that there is ‘continuous personal supervision’, which some take to mean a registrant checking every aspect of the trainee’s work, however, the inclusion of ‘ie be in the practice when the student is in professional contact with patients and be able to intervene as necessary’ goes against this notion and allows for a gradual freeing of the reins.

The important point is that each non-qualified person carrying out a restricted delegated function has a named supervisor that can be identified in the event of complaint or concern and the amount of free rein that is given is a matter between the supervisor and supervisee. If the supervisor is happy, having repeatedly checked their work, that the student is competent to perform the delegated task and sufficiently aware of the limits of their competence to ask for help when required then the student may be left to work with a minimum level of supervision, namely that the supervisor is available to them should they need assistance.

Supervisees often struggle to come to terms with the different stances of different individual supervisors. They may be given a free rein one day, and be held on a tight leash the next, but ultimately it is the supervisor who is accountable for any error or malpractice and they must be sure of the competence level of their charges. Dentistry and pharmacy get round this problem by insisting on training for clinical assistants and on registration and qualification respectively so that locum practitioners can have some assurance that junior colleagues are competent in their delegated functions.

Academic supervisors of student optometrists and dispensing opticians have additional responsibilities to: support, observe and mentor; provide a sufficient and suitable learning environment; ensure the student has access to the appropriate equipment to meet the requirements of the Route to Registration; be familiar with the assessment requirements, guidelines and regulations of the Route to Registration; and ensure that when the student is in professional contact with patients they are clearly identified as a trainee under supervision and that the identity of the supervisor is also made clear to the patient.

Duality of communication

Every paediatric dispensing provides an opportunity to educate both parents and child on the law and importance of seeing a registered dispensing optician or optometrist. Educating the public using clear messaging regarding the importance of eye care and the role of each eye care practitioner positively promotes the optical professions and enables better understanding of the part each eye care practitioner plays in eye care delivery.

Communicating effectively with both the child and the parent/carer is essential and is part of the specific GOC paediatric competency4 requirement for dispensing opticians. Griffiths3 uses the term ‘duality of the patient’ as balancing requirements of both the child and the parent particularly when they differ can be challenging. This duality often leads to conflict and the satisfactory resolution of conflict is the hallmark of a competent practitioner of paediatric dispensing. There are many everyday examples, where children conflict with their parents, or where both disagree with the dispensing practitioner. This may be as simple as the child wanting branded or designer frames and the parents only being prepared to agree to those that are provided free at the point of service (paid for by the National Health Service). It is not uncommon, especially if the dual patient has been allowed to try on frames without assistance, for a frame to be chosen that is entirely inappropriate and it is a difficult conversation to convince the child/carer that they need to start again. Complex dispensing especially when combined with specific facial characteristics demand a more restricted frame choice so from the outset the dispensing optician, optometrist or their supervisee, needs to set parameters for frame selection ensuring a positive outcome and avoiding any conflict.

Conflict resolution

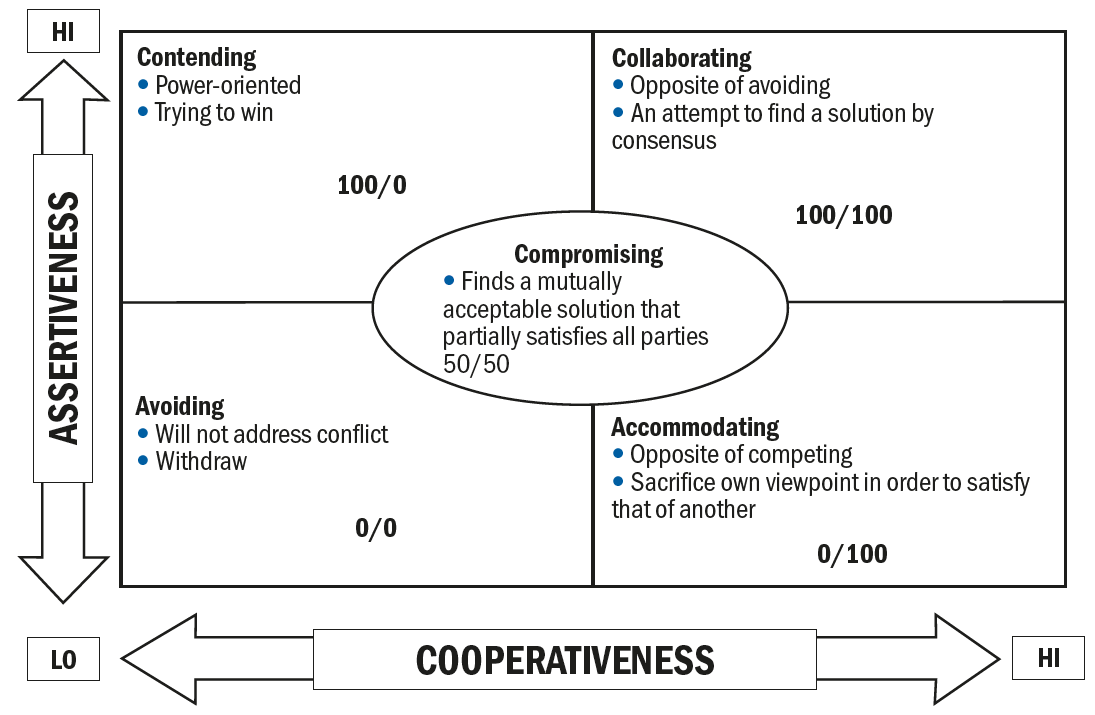

When placed in a difficult situation it may be helpful to think of a model of conflict resolution, always remembering that it is an optician’s duty to always act in the best interest of the patient. The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument is one such model (figure 1) that plots concern for oneself or one’s business (assertiveness) – against concern for the patient (cooperativeness) and is useful in many customer service/concern/complaint situations.

Figure 1: The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

Figure 1: The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

If we take a common situation where a child has chosen a frame with their parents that is then felt to be unsuitable by the optician, say because the boxed centre distance is too large and requires excessive lens decentration, and/or because the total side length will result in an excessive length to bend or length of drop that cannot be shortened.

Avoiding conflict would mean conducting the dispense without challenging the frame choice, kicking the can down the road for the inevitable patient/parent dissatisfaction to be dealt with later. Although this may seem expedient when a practice is short staffed and there is a queue of patients it leads inevitably to a remake or refund. As both parties are disadvantaged avoiding conflict is a lose-lose situation. In general, this approach more than doubles the amount of work required to deal with an individual patient – practices with high remake rates are often trapped in a cycle where inexperienced and/or uncaring staff take the quickest route to dealing with the patient because they are too busy, not recognising that it is this attitude that has caused the extra work in the first place.

Accommodating a patient’s wishes at the practice’s expense may be entirely appropriate if you have already caused them significant dissatisfaction or inconvenience. In this example, if the patient returned because they had not been advised that the frame was unsuitable, then it might be entirely appropriate to provide the patient with a more expensive frame or lens option at no additional cost if that was the only solution acceptable to them. Practitioners are sometimes indignant that they should not have to provide additional compensation and are often seen to ‘cut off their nose to spite their face’. Ultimately if the spectacles were not fit for purpose the patient could demand a full refund/return of their NHS voucher and it is unlikely that any free upgrade would cost the practice as much as this. Losing today may mean winning in the future.

Contending or competing is the opposite of accommodating, and in this instance might involve adjusting the specs as far as possible but refusing to exchange them when they are clearly not fit for purpose. The author has previously negotiated with a competitor professional colleague on behalf of a patient when the practice refused to exchange or refund on spectacles that fitted so poorly, they prevented the child from breathing through their nose. Contending is not in the patient’s best interest and is viewed dimly by regulatory authorities.

Collaborating refers to a problem-solving approach to conflict resolution and after the problem has been outlined by the parent/patient may begin with a simple question along the lines of: ‘If I could grant anything what would you like me to do?’ Most patients/parents just want a fit for purpose pair of spectacles and nothing more and this results in a true win-win situation – the patient gets what they want and the practice fulfils its obligations at minimal cost.

Compromising is the middle ground on the conflict resolution model where each party gains but must also give up something of their initial bargaining position. These 50:50 situations are sometimes inevitable and it is important to set patient expectations appropriately. In the situation where a child is insistent on a frame that is judged to be less than ideal (rather than completely unsuitable) it is better to dispense a compromise solution that the child will use than a perfect solution that the child will not wear so sometimes a compromise is the only option. With amblyopia in particular, full-time wear is vital if the treatment is to be successful and if a particular colour or brand makes that possible it is an acceptable compromise.

Visual development

At birth the average refractive error is about +2.00D which decreases rapidly between six months and two years with emmetropisation occurring around the age of six years.5

Normal development of the primary visual cortex (V1) is dependent upon binocular vision during the critical period, this is considered to be from birth to around age seven or eight years although recent studies suggest some plasticity extends into adulthood.6 Abnormality in V1 neurodevelopment leads to impaired vision in one eye or less frequently both eyes. Amblyopia is a reduction in visual acuity after best correction where no pathology or structural abnormality is present usually diagnosed by a two-line difference in recorded best corrected visual acuities. Prevalence of amblyopia in Europe, which includes the United Kingdom (UK), is around 2-3%.7,8

The two main causes of unilateral amblyopia are anisometropia and strabismus, with strabismus more common; however, this is most often due to uncorrected hyperopia and the associated accommodation causing a convergent squint. Treatment of amblyopia is extremely effective in children under seven years with ~75% achieving resolution using patching or atropine, essential to any treatment is having the best possible refraction.9

This highlights the need for school vision screening to check uncorrected vision and binocular vision status. Unfortunately, although School Vision Screening is ‘recommended’ by the National Screening Committee across the UK it is only mandated in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland where health policy is devolved. As a result, school vision screening in England has become a postcode lottery and has ceased to exist altogether in many parts.

There is a clear public health obligation for optical practices to check with adult patients that are accompanied by children, or parents of child patients whose siblings accompany them, whether the child has ever had a full eye examination. Although parents are often sceptical that the practice may simply be trying to make money, a simple leaflet explaining the benefits of regular paediatric eye care is an effective communication medium. This is further emphasised by a survey conducted by Donaldson, Subramanian and Conway10 where only 22% of parents with a child having poor concentration in school would consider taking the child for an eye test and worryingly only 18% would consider an eye test for a child that had achievement and literacy difficulties. This study also pointed out the lack of parental knowledge or education relating to paediatric eye care.

Paediatric dispensing

So far, we have dealt largely with regulatory, communication and public health issues relating to paediatric dispensing, and in previous articles we have defined the measurements and frame characteristics that will form the basis of the following

discussion.

Paediatric facial anthropometry

Anthropometry is the science of measurement of human beings and demonstrates clearly that children’s faces are not simply a scaled down version of their adult face. As development of individual structures varies with age this can make frame selection more challenging as the frame must fit securely without impeding any natural development of the ears or nasal structures. This in turn impacts the inventory or stock levels that practices must hold if they are to satisfy the fitting requirements of children let alone their fashion demands.

To some extent the requirements for multiple sizes and a variety of length to bends, crest heights etc has been accommodated by specialist paediatric frame suppliers such as Tomato whose frames have bridges that can be removed and reattached at different crest heights using screws, and similarly adaptable side fittings. See figure 2.

Figure 2: Tomato frames have the ability to alter the crest height and length to bend to accommodate a wider range of children than standard frames

Figure 2: Tomato frames have the ability to alter the crest height and length to bend to accommodate a wider range of children than standard frames

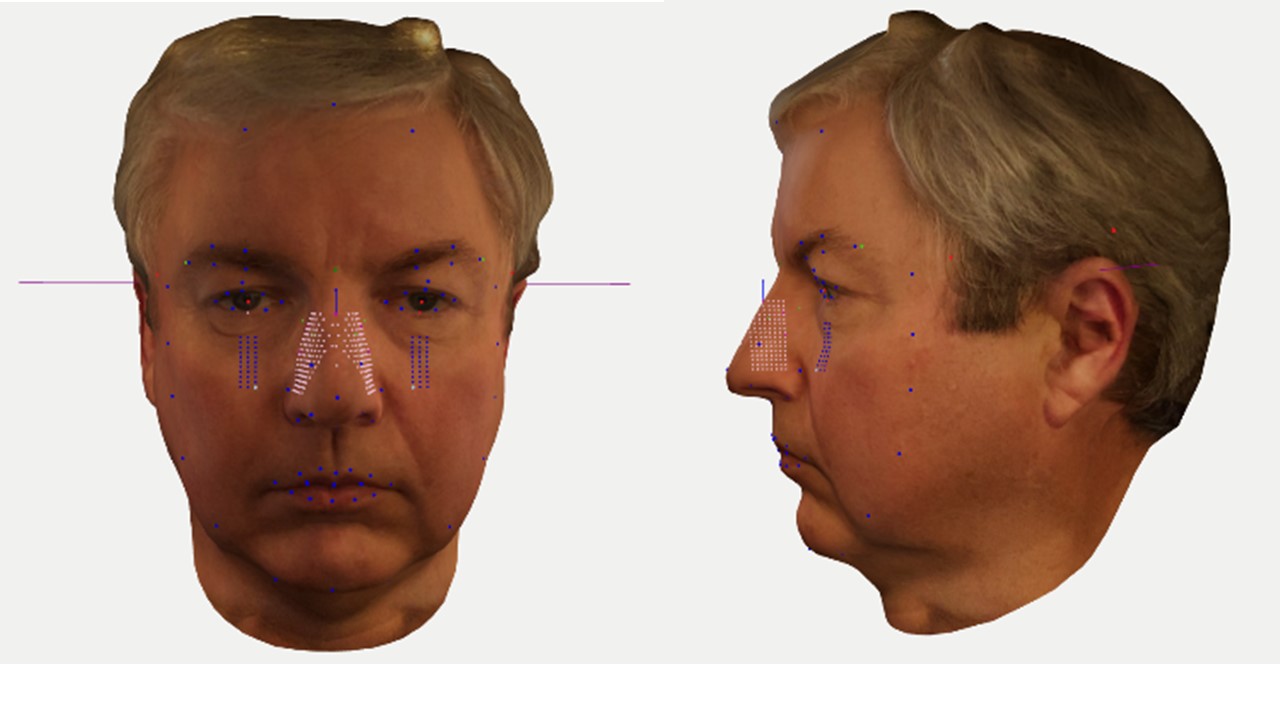

Anthropometric data is becoming easier to collect using facial scanning applications (see figure 3) and is an emerging research field in the eye care sector. The data demonstrates that children’s frame dimensions must differ from adults’ styles to reflect the fact that they need to have a lower crest height with larger frontal and splay angles, and a less positive/more negative bridge projection. High cheeks mean a pantoscopic angle around zero is often required and obviously head widths and temple widths will be reduced.

Figure 3: New 3D scanning applications are allowing easy collection of anthropometric data from (above) adults and (below) children alike

Figure 3b shows a superimposition of a very small adult frame on a scanned image of a three-year-old boy matched by artificial intelligence as the best fitting frame in the available database of adult frames. Even if scaled to fit, it is clear that a correctly fitting frame would require a much lower crest height and a mini-me copy would not be appropriate.

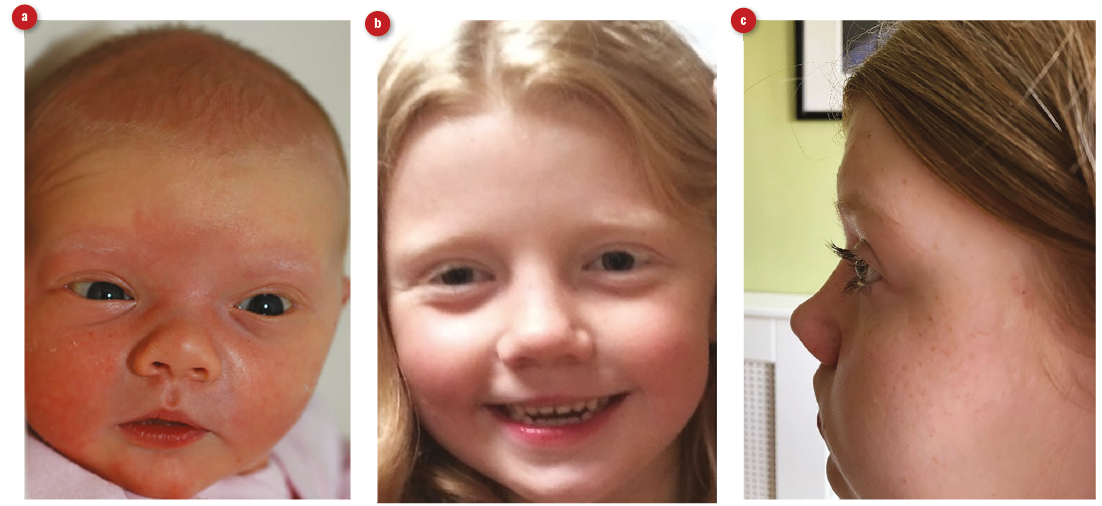

The data also reveals that, even in teenagers, adult facial characteristics, in particular a pronounced bridge to the nose, are not yet developed. Figure 4 shows the same child at ages three days, four years, and 13 years. At all ages, this child requires a negative bridge projection in order to prevent the lashes rubbing on the lenses.

Figure 4: Facial appearance of (a) child of three days old, (b) child at four years old and (c) a 13-year-old teenager. For the older child, a negative bridge projection may cause eyelashes to touch the lenses

Figure 4: Facial appearance of (a) child of three days old, (b) child at four years old and (c) a 13-year-old teenager. For the older child, a negative bridge projection may cause eyelashes to touch the lenses

Teenagers

Paediatric dispensing is not simply concerned with young children, older children can also present considerable challenges when dispensing. Facial anatomy continues to develop throughout life and many practices complain that they find it difficult to have a wide selection of frames that are suitable for teenagers. Fashion and personal taste take on an increasingly important role, however, mini-me adult frames are not be ideal especially in plastic styles. Figure 4c shows that even in teenagers the bridge of the nose may not yet be sufficiently developed, and when combined with long eyelashes may result in a negative bridge projection that is difficult to accommodate with plastic fixed-pad frames and results in them being worn down the nose causing the patient to look over the top. This ‘style’ is so common at the school gates it might be considered normal or acceptable. Eyelashes rubbing on the lenses is unbearable but can easily be compensated for with adjustable pads on arms by pulling them backwards to push the front forwards and thereby increase the vertex distance. With high-powered prescriptions this needs to be done at the time of the dispense so that the vertex distance can be measured and the prescription then compensated accordingly.

Teenage patients often have fixed views of what they want based on the spectacles worn by their friends or favourite popstar or actor. As with any supply of an optical appliance there is a duty to gain valid informed consent. Despite a patient knowing what they want, is it essential that any drawbacks are compared with other alternatives. This applies especially to first time spectacle wearers who will largely be unaware of the features, benefits, and disadvantages of different kinds of frame. It is all too easy to accept a request for the latest fashion – dark plastic fixed pad frames at the time of writing – without explaining other alternatives such as metal or supra frames and rimless mounts. A wise addition to any practice’s frame stock is a range of plastic frames with adjustable pads on arms that may successfully bridge the fashion and fitting requirements without having to compromise on either.

Gillick competence

Teenage patients can also present other challenges, especially if they attend without a parent or guardian for an eye examination, contact lens appointment or spectacle dispensing. Contrary to popular belief it is perfectly possible to obtain valid consent from a teenage patient to any optical service, providing in the opinion of a qualified registrant, the patient is Gillick competent. Gillick competence refers to a judgment following Gillick v West Norfolk in 1984 that deemed a 14-year-old girl ‘competent’ to have the capacity to consent to oral contraceptives without the need for parental involvement. It is therefore acceptable for a competent child to agree to the supply of a medical device providing they are not entering into a contract on their parents’ behalf (such as a direct debit or financial transaction to which the parent has not agreed). GOS forms say that a child’s parent SHOULD sign on their behalf, but they do not say MUST. This means legally the child may sign their own forms if competent to do so, with children who have attained the age of 16 automatically assumed to have the capacity to consent. A common complaint from parents is the refusal to allow a teenage child to collect their spectacles or contact lenses on the way home from school. There is no reason this cannot happen providing there is a qualified registrant on the premises and they deem the child to be competent and this should be noted on the record.

Next time you are about to inconvenience a child who is clearly mature enough to collect their own spectacles, think about the actual Gillick case. Here, the highest court in the land accepted that a 14-year-old girl was mature enough to understand about sexual intercourse, contraception and the risks of pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases etc. A child collecting their spectacles without a parent is still a restricted function that requires registrant intervention, but that should not stop the provision of good customer service.

Note that the other common complaint, the parent collecting spectacles for an absent child is not generally permissible since the fitting must be carried out by or under the supervision of a registrant and without the child this cannot happen. Where this proves impossible, due to Covid restrictions for example, then every effort must be made to ensure a perfect fit in advance by adjusting the frame to the correct fitting through the routine measurement of head width, length to bend, angle of side etc. It is hoped taking these measurements and setting up frames properly in advance this will become the norm in future – it saves a lot of time in collection clinics and provides a better overall service that should not be reserved for global pandemics and other exceptional situations.

Lens materials

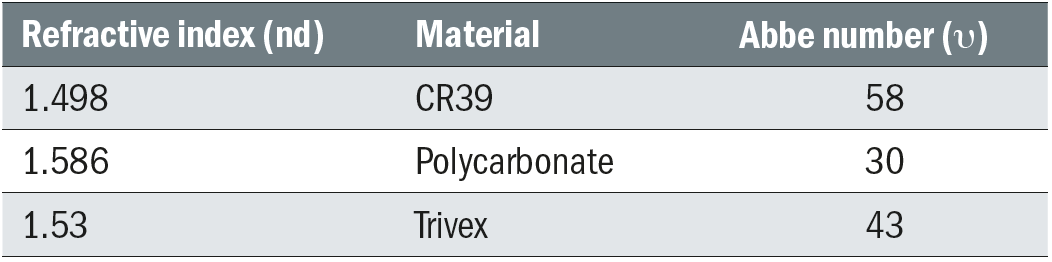

While safety is paramount in paediatric dispensing lens properties need also to be considered. Glass lenses should be completely avoided in favour of a robust plastics material, the choice of which is debatable. Polycarbonate has the greatest impact resistance but a low Abbe number (see table 1) leading to reduced off axis visual acuity due to chromatic aberration, which is exacerbated by inaccurate centration or when frames are knocked out of alignment. The importance of the best retinal image to ensure a child reaches full visual potential particularly during the critical period is essential so materials like Trivex and CR39 should be considered. Trivex offers a greater impact resistance than CR39 and has better image forming properties than polycarbonate but is more expensive when compared to CR39. Ultimately lens material is a choice for the parent of the child if they are unable to decide for themselves, yet how often does a company offer a specific product without giving the patient either information about the alternatives or a real choice?

Table 1: Optical lens material properties

Table 1: Optical lens material properties

Informed consent should take into account factors like the age, any medical conditions and how active a lifestyle the child has. If the child participates in sports activities like football, rugby, swimming or tennis, a separate specific sports appliance and/or contact lenses must be offered as part of the process.

Conclusions

Paediatric dispensing is an important responsibility that is restricted in law. Here we have built on previous articles on frame measurements and lenses and taken a legalistic view of the issues building on the previous article. Many issues relating to restricted dispensing are misunderstood, perhaps none more so than supervision. Regardless of company policies or practice standard operating procedures supervision is a matter between the supervisor and supervisee. Certainly, practices should make registrants aware they are expected to supervise, and certainly supervisees should know to only work to the limits of their competence and ask for help when necessary but the decision on the level of intervention required is that of the supervisor alone.

We will return to the practicalities of paediatric dispensing in a future article on dispensing children with special needs.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO is senior lecturer in ophthalmic dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians.

- Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CET provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College.

References

- Keirl A. Paediatric eyecare – part 2, Anthropometry and spectacle frames for children. Dispensing Optics 2010.

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. London. General Optical Council; 2016

- General Optical Council. GOC highlights importance of student supervision. Available from: https://www.optical.org/en/news_publications/news_item.cfm/GOC-highlights-importance-of-student-supervision Accessed 23rd June 2021.

- General Optical Council. CET requirements for registration. Available from: https://www.optical.org/en/Education/CET/cet-requirements-for-registrants.cfm Accessed 23rd June 2021.

- Flitcroft D. Emmetropisation and the aetiology of refractive errors. Eye. 2014; 28:169-179. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/eye2013276 Accessed 23rd June 2021

- Hensch T, Quinlan E. Critical periods in amblyopia. Visual Neuroscience. 2018; 35. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6047524/ Accessed 23rd June 2021.

- Hashemi H, Pakzad R, Yekta A, Bostamzad P, Aghamirsalim, Sardari S. Global and regional estimates of prevalence of amblyopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Strabismus. 2018; 26 (4). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09273972.2018.1500618 Accessed 23rd June 2021.

- Fu Z, Hong H, Lou B, Pan C, Liu H. Global prevalence of amblyopia and disease burden projections through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2019;104; 1164-1170. Available from: https://bjo.bmj.com/content/bjophthalmol/104/8/1164.full.pdf Accessed 23rd June 2021.

- Gunton K. Advances in amblyopia: What have we learned from PEDIG trials?. Paediatrics. 2013; 131(3):540-547. Available from: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/3/540 Accessed 23rd June 2021.

- Donaldson L, Subramanian A, Conway M. Eye care in young children: a parent survey exploring access and barriers. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2018;101(4);521-526. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cxo.12683 Accessed 23rd Jue 2021.