Early 2021 saw a doubling in adult mental health related issues with changes in individual’s behaviours and lifestyle choices compared to before the pandemic.¹ As a result of these challenging times, health care delivery is embarking on a digital transformation journey to meet modern demands.² With so much change and uncertainty that has presented itself in recent times, some will find they are subconsciously placing psychological barriers to further change including unexpected professional advice and as a result be non-compliant.³

“2x increase in mental health issues in 2021”

With regards to optometry the recent GOC survey can provide reassurance that public perception of eye care professionals remains high, with 94% either fairly or very confident in the standards of care and an upward shift to over a third who perceive optometrists to be a solely health care service.4 This article explores how we can increase confidence in the remaining 6% and influence patients attitudes who may not be aligned with our clinical management plans. This builds on the first article which highlighted simple effective ways eye care professionals can include aspects of health and well-being into eye care services.5

Case Scenario 1

An 81-year-old gentleman presents with reduced vision. He is a driver and smoker. Previous records from his last eye examination three years ago reports dry AMD and cataracts in both eyes, with an Amsler grid and leaflets provided. Examination today reveals suspect wet AMD in the right eye. Binocular vision acuity is now 6/15. He is on various medications for blood pressure and anxiety.

Management

You explain your findings and advise him that you will arrange a referral to the eye hospital. You mention the DVLA requirements. Until this point, he has been silent and suddenly he responds angrily declaring that he will not be attending any eye hospital or cease driving. How would you respond?

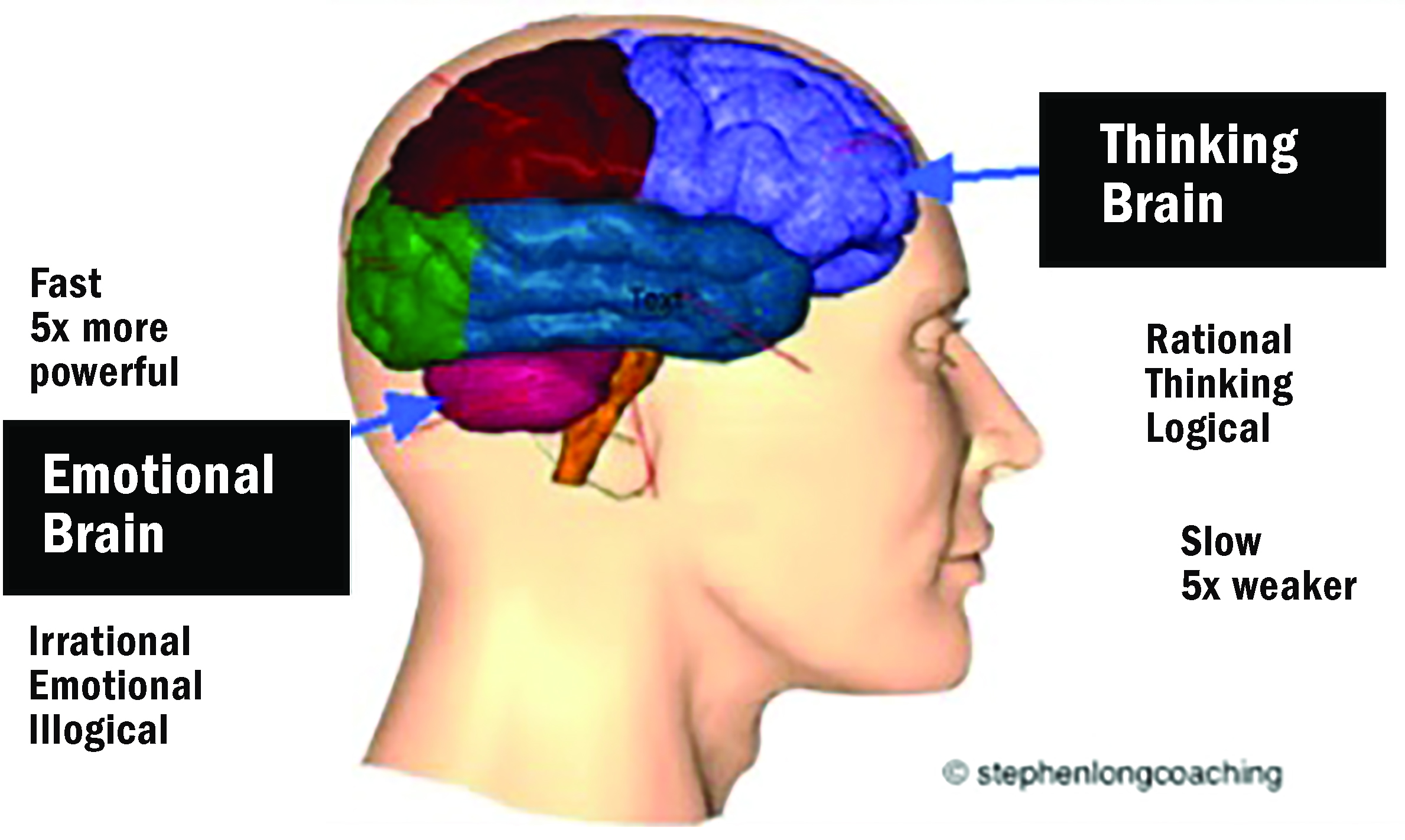

We can take the topic of informing others such as the DVLA as beyond the scope of this discussion and firstly should focus on the reason as to why this reaction may have occurred. It is likely that the communication approach has stimulated a strong emotional response, activating the amygdala (part of the brain’s limbic system, responsible for fear). How we communicate is essential and research has shown that by using techniques that we will discuss later, such as labelling the emotion and applying words to the fear, the mindset can be shifted to activate rational thinking responses in the prefrontal neocortex (figure 1).6

Figure 1: The thinking/emotional brain

Figure 1: The thinking/emotional brain

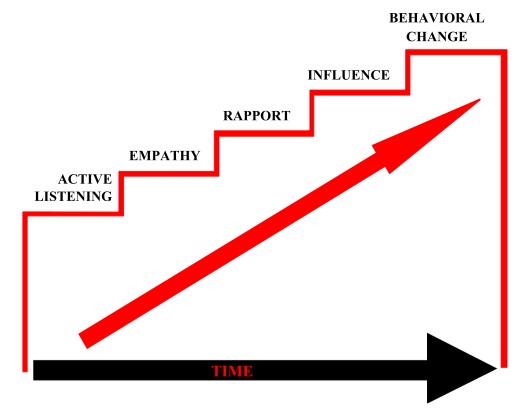

For inspiration we can learn from negotiation experts and adapt the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) behavioural change stairway model7 as outlined in figure 2.

Figure 2: The FBI’s five stages of the behavioural change stairway model

Figure 2: The FBI’s five stages of the behavioural change stairway model

Active listening and observation

Asking general open questions regarding the individual’s health and wellbeing can reveal clues to how they may react to new information. At this initial stage you are simply gathering information and should respond in a manner to reassure them that they are being heard and understood.

For example, you may identify he is the main driver and a loss of independence could impact the wider family. He may have a fear of hospitals? Find out what he knows about his current condition? How does he feel today? How has he adapted to the new situation? What is his main concern? Explore their assumptions?

Observe their body language, habits, eye contact and the way they respond. Does the patient fold his arms in defensiveness, or look away/lower his gaze to avoid eye contact?

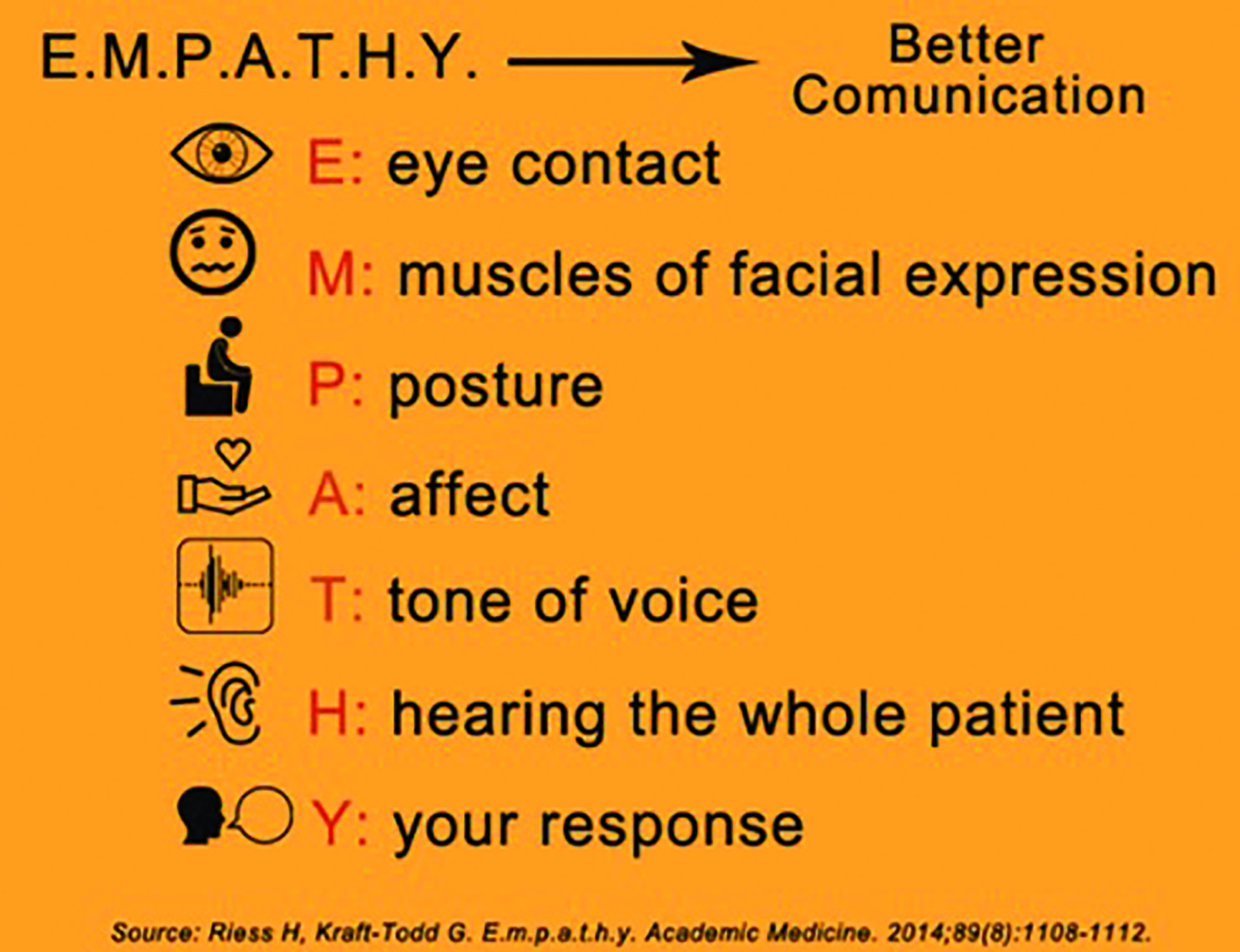

Empathy

Relate to the patient showing empathy, and consider how you may come across – be calm, radiate warmth, care and smile where appropriate. Be mindful to slow the pace to create a feeling of safety and so they know you in listening mode.

For this situation you may use phrases such as “I understand your independence is important to you…”

A good acronym to follow8 is in figure 3.

Figure 3: The Empathy approach to promote clearer lines of communication

Figure 3: The Empathy approach to promote clearer lines of communication

Rapport

Showing an interest in them and their concerns in a caring way will help build relationships. You are not necessarily agreeing with them but being supportive.

“I hear your frustration….”

Influence

Once trust has been gained guidance to help with their problems can be recommended, reframing a negative thought process with a positive mindset. Explanations, reassurance and solutions that can be discussed together. What could be done to go the extra mile for the patient? Can you provide additional support network details?

Behaviour change

Give opportunities to ask questions and establish mutually agreed outcomes. How truly committed and accepting are they to any of the outcomes, are there any further limitations holding them back? It is important to gain commitment to any actions necessary and record keep this accordingly.

Case Scenario 2

A 55-year-old female who was diagnosed with diabetes 10 years ago presents with signs of mild diabetic retinopathy changes. She has missed her last retinal screening appointment due to the pandemic but was told previously that there were ‘minor changes’ but no treatment was required. She takes metformin, ramipril and statin medications and is unsure of the dosage or her control levels.

As you explain your findings to the patient, she says she is not surprised as due to personal circumstances she has not been staying on top of her diet or fitness. She then becomes visibly upset and teary as she states she wished she had put her health first instead of everything else.

This is a great opportunity for active listening and taking time to understand what has been happening in the patient’s life for her to neglect her own health. Ensure your body language is open, you are facing the patient, and your tone is soft so the patient feels you are caring rather than judging.

Asking her open questions9 such as ‘can you tell me what’s been happening in your life that’s kept you busy’? ‘What have you been struggling with?’ Once you have established the cause it is important to explore what support they have.

Gently advising her on the potential future consequences of the diabetic retinopathy advancing, followed by positive encouragement of the benefits of lifestyle changes to reduce the risks. National survey data also highlight basic knowledge gaps among many diabetics – less than 50% know their level of glycaemic control, 63% know their blood pressure with education helping to improve compliance and reduce anxiety.10 Now we have great technology to help explain and reassure regarding eye health, such as using OCT, or fundus images.

Questions on nutrition such as ‘what changes do you think you can make to your diet?’, ‘what could you add or take away to make your nutrition better?’, ‘would you benefit from speaking to a dietician or nurse to support you?’

‘What fitness activities do you enjoy?’ ‘Could you schedule it in maybe once or twice a week?’ Using reinforcement such as ‘imagine how amazing you’ll start to feel,’ ‘this is really going to give you so much more energy,’ ‘you’ll feel proud of yourself when you take that first step,’ are important in creating a success mindset.

Good questioning and getting the patient to come up with small bite-sized solutions that are doable will ensure that the patient feels confident and motivated to do them, and has a good understanding as to why it will benefit her.

Case Scenario 3

A 14-year-old hyperopic patient attends for a routine eye exam. She says her vision is fine, noticed no changes and that she does not feel the need to wear her glasses that were prescribed last year.

Upon refraction you discover refraction has become significantly worse, therefore you suspect there must be an underlying reason as to why she feels she does not need to wear her spectacles.

You gently explain the findings to her and show her on direct comparison how much of an improvement to her vision wearing glasses makes. You notice she becomes a bit stiff and defensive in her body language.

This is where communication, empathy and understanding is important.11 Asking questions such as ‘do the frames feel comfortable when you wear them?’, ‘do you still like the style of the frames?’, ‘do many people in your class wear glasses?’, ‘how does wearing glasses make you feel?’, could all help in understanding why she does not like to wear them. Appearance and how we think others see us can really impact our mood and emotions during the teenage years.

She then opens up and says that she felt image conscious wearing them and that her friends were telling her she does not suit glasses, which made her lose her confidence so she stopped wearing them.

A good place to start here is understanding and resonating with the patient as this is a sensitive area for her. Maybe giving an example of something similar you went through or someone else you may know (without giving personal details), this can help the patient feel understood, heard and not alone. Teenagers always feel they are told what to do either by parents, teachers and other adults this is a good opportunity to come to a conclusion together.

Asking the patient what would help her to feel more comfortable wearing glasses? Would different frame styles help? Maybe exploring together the latest frame trends? Has the patient considered contact lenses? With permission from parents, maybe she would like to see or even trial contact lenses?

Working on her confidence is the key part here, so encouragement and praise would help boost her self-esteem. Telling the patient how certain frames would really suit her, how certain colours would really compliment her etc.

If the patient has come in feeling anxious and apprehensive, our role is to make her understand the importance of her vision, but also to make her feel good and give her a variety of recommendations that would suit and make her feel comfortable.

What to do if this has not worked

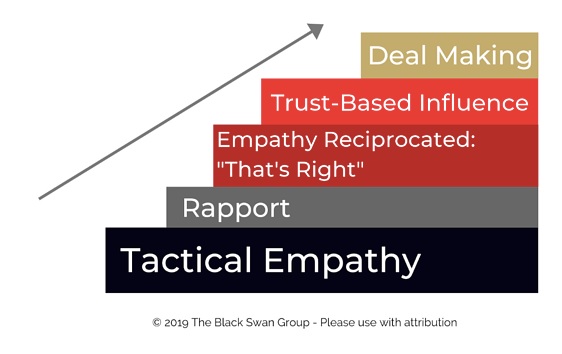

An interesting strategic approach is to follow the Voss and Raz¹² model of using tactical empathy as a vehicle to develop rapport and trust to change their mindset as illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4: The Voss and Raz model of using tactical empathy

Figure 4: The Voss and Raz model of using tactical empathy

How can we achieve this to persuade our patients who reject our advice?

- Pause and prepare – avoid a knee-jerk reaction to try to force them to admit you are right. First breathe and think, prepare yourself mentally.

- If you need to distil emotions such as anger, acknowledge it, keep calm, often starting with an apology helps and label their emotions ‘I am sorry to hear…’

- Actively listen applying tactical empathy to understand their feelings and the mindset behind those feelings. ‘During these challenging times I understand…’

- Use mirroring, labelling and paraphrasing techniques to repeat their perspective back and to engage them into a solutions-based discussion. ‘It seems like…’

- Use calibrated questions focusing on solving the problem. ‘What about this does not work for you?’ ‘How can we solve this problem together?’

- Summarise your advice linked to benefits to generate a ‘that’s right moment’. Make use of pauses to give them processing time to digest your recommendations. Silence is powerful.

If this has not elicited the optimal commitment, then arranging a follow up discussion is advisable, giving the individual time to process the information. Often there is a ‘black swan’ some information that if known may have generated a different outcome. Offer time for reflection and information processing.12 A suggestion to include others to help support the future conversations may be advisable. If you would like more advice then professional organisations such as the AOP, ABDO, COO all have guidance and/or professional advisors, also MIND and the NHS website.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is a link between mental health and progression of ocular manifestations of disease13 and we can support, motivate, and educate patients. Asking simple questions can prompt small steps towards new habits, this is the rationale behind health care professionals asking ‘Do you smoke?’ If yes: ‘Would you like smoke cessation referral?’ Sometimes our patients will not follow or agree with our management plans and on occasions compromise is not the best option.

A similar concept is imagining Neil buys Sheena some new stiletto shoes for her birthday, with the plan that day to go hiking. Sheena insists on wearing the new shoes, Neil insists hiking shoes would be more appropriate. Would the answer be to compromise and wear one of each? No. By using our clinical, personal and the skills discussed we have a chance of making a positive difference to our patients emotional and physical wellbeing as well as ocular health.

- Neil Retallic is an optometrist with experience of working within education, industry and both practice and head office roles. He currently works for Menicon and the College of Optometrists. He has been involved with various

organisations across the sector and is currently part of the GOC Education Committee, President Elect of the BCLA and a Past Chair of the British and Irish University and College Contact Lens Educators. He has been awarded fellowships from the BCLA and IACLE. - Sheena Shah is an optometrist working in practice currently at Vision Express. She is also an author, rapid transformation therapy practitioner, life coach, mindfulness, meditation, NLP practitioner and nutritionist, working with individuals, families, businesses and schools under her wellbeing company Inspiring Success.

Useful support and resources

Mental health and well-being

- Samaritans; general well-being

- Helpline: Freephone 116 123

- www.samaritans.org

- Mind; general mental health support

- Helpline: 0300 123 3393

- Website: www.mind.org.uk

- Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM); may be able to offer her support with the stress of balancing home life

- Helpline: 0800 58 58 58

- Website: www.thecalmzone.net

- No Panic; specifically, for people who suffer panic attacks (need to gauge usefulness here)

- Website: www.nopanic.org.uk

Case 1

- Macular Society; all matters macular

- Helpline: 0300 3030 111

- Website: www.macularsociety.org

- Silverline; telephone network for like-minded elderly of similar experience, interests and intellect

- Helpline: 0800 708090

- Website: www.thesilverline.org.uk

- Aged UK

- Helpline: 0800 6781602

- Website: www.ageuk.org.uk

Case 2

- Diabetes UK; all matters diabetic

- Helpline; 0345123 2399

- Website; www.diabetes.org.uk

Case 3

- Young Minds; support for teenagers with mental well-being

- Helpline; Parents’ Helpline: 0808 802 5544

- Young person support; for urgent help, text YM to 85258 for free 24/7 for professional support across the UK

- Website; https://youngminds.org.uk

References

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest insights - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk). Accessed 06/07/21

- Wanat M et al. Transformation of primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of healthcare professionals in eight European countries. Br J Gen Pract. 2021 May 11:

- Bucci S, et al. The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care. Psychol Psychother. 2019 Jun;92(2):277-297.

- General Optical Council. 2021_public_perceptions_research.pdf (optical.org). Accessed 06/07/21

- Retallic N, Shah S. Health and well-being in eye care practice. Making the difference to your patient’s life. Optician 2021 January 15

- Lieberman MD et al. Putting feelings into words: affect labelling disrupts amygdala activity in response to affective stimuli. Psychol Sci. 2007 May;18(5):421-8

- Vecchi G et al. Crisis (hostage) negotiation: current strategies and issues in high-risk conflict resolution. Aggression and violent Behaviour 10 (2005) 533-551

- Riess H, Kraft-Todd G E.m.p.a.t.h.y Academic Medicine. 2014.89(8)l1108-1112.

- Covey S.The 7 habits of highly effective people Simon & Schuster Ltd. 2017

- Gonzalez JS, Tanenbaum ML, Commissariat PV. Psychosocial factors in medication adherence and diabetes self-management: Implications for research and practice. Am Psychol. 2016;71(7):539-551

- Whitemore J. Coaching for performance Nicholas Brealey Publishing 2017

- Voss C and Raz T. Never Split the Difference Negotiating as if your life depended on it. Pengium Random House Business 2016

- Nicolucci A, Burns KK, Holt RIG, Comaschi M, Hermanns N, Ishii H, Peyrot M. Diabetes attitudes, wishes and needs second study (DAWN2™): Cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2013;30(7):767–777