A number of definitions have been provided for presbyopia over the years and these typically relate to either functional or objective assessments. In a recent publication describing the mechanisms for, and correction of, presbyopia, the following definition was proposed: ‘presbyopia occurs when the physiologically normal age-related reduction in the eyes focusing range reaches a point, when optimally corrected for distance vision, that the clarity of vision at near is insufficient to satisfy an individual’s requirements.’1

It has been estimated that presbyopia affected 1.8 billion people or 25% of the world’s population in 2015, and this is expected to be at least 2.1 billion in 2030.2 The prevalence varied according to region, with North America estimated to be 32%, Australia and New Zealand 33% and Western Europe 39%.2 A recent report estimated 2.8 billion presbyopes globally by 2030.3 The world’s population is ageing; for example, in 2019, 44.3% of the United Kingdom (UK) population was aged 45 or older, with a median age of 40.1 years;4,5 and in the United States (US) it was slightly lower at 41.8%, with a median age of 37.7 years.6,7 As a result, increasingly more patients require presbyopic vision correction which can be provided by spectacles (progressive addition lenses (PALs), bifocals and trifocals), single vision contact lenses (CLs) used in conjunction with spectacles for reading, monovision CLs, multifocal (MF) CLs and sometimes surgical correction. A recent bibliometric study reported that research on MFCLs has shown exponential growth and shows no signs of slowing.8

In the first of two articles, we provide an overview of current attitudes and beliefs relating to presbyopia and MFCLs, requirements for presbyopic CL correction, MFCL design options and performance comparisons with monovision CL correction. The second article will cover prescribing trends for both MFCLs and 1 day CLs, recommendations for prescribing, supplemental fitting tools and patient satisfaction with MFCLs.

Insights and Perceived Barriers

Despite presbyopic patients representing an ever-increasing opportunity for prescribing CLs for vision correction, many Eye Care Professionals (ECPs) continue to be reluctant to offer MFCLs to their patients. In a recent online survey of 200 US ECPs and 178 UK ECPs, 33% (US) to 37% (UK) of patient populations were reported to be presbyopic; however, in the US, ECPs reported recommending spectacles only for 55% of their last 100 presbyopic patients and MFCLs for only 28%, and in the UK the numbers were 60% and 27% respectively.9

In an international survey investigating CL prescribing for presbyopia between 2005 and 2009, Morgan et al hypothesised that the principal barriers to fitting MFCLs were a lack of fitting skills, technical knowledge, product awareness or clinical confidence among ECPs, along with the general preconception that visual compromises introduced by available presbyopic designs were too great.10 A subsequent survey conducted in India reported that the most common potential barriers were increased chair time, a lack of readily available trial lenses and limitations in power range.11 However, in the same survey, ECPs who were actively fitting MFCLs reported that their main motivators in prescribing these lenses were professional satisfaction and enhanced business opportunities; furthermore, these ECPs reported that their success in MFCL fitting was enabled by increased confidence due to trial lens availability and correct patient selection.11 Some examples are provided in the accompanying side panels on insights from some ECPs in the UK .

Perceptions do appear to be changing though and, in the 2020 Global Multifocal Benefit survey, only 4% of ECPs in the US and 7% of ECPs in the UK strongly agreed with the statement ‘Fitting MFCLs is difficult and takes up too much chair time’.9 In addition, only 14% of ECPs in the US and 18% of ECPs in the UK strongly agreed with the statement ‘I do not think there are enough prescription options for the needs of my presbyopic patients’. Consistent with the ECPs surveyed in India,11 the ECPs in the US and UK saw an opportunity for enhanced business opportunities with 77% and 73% in the US and UK respectively strongly agreeing with the statement ‘Presbyopic patients who wear MFCLs and progressive lens spectacles offer additional practice revenue and profit’.

Wearer Perceptions

Hutchins and Huntjens have recently published the results of a quantitative (online survey) and qualitative (focus group sessions) study which was designed to investigate the attitudes and beliefs regarding presbyopia, its significance and methods of vision correction.12 While the 24 UK participants of the study were aware of presbyopia being a ‘natural ageing process’ and accepting that it would occur ‘between 40-45 years’ or in ‘mid 40s’, very few were familiar with the term presbyopia. Some participants suggested that being forewarned of the onset of presbyopia prior to its onset, would encourage awareness and regular visits to the ECP. Perhaps not surprisingly, both pre-presbyopic and presbyopic participants who were not habitual CL wearers for distance vision expressed reluctance towards MFCLs. In contrast, the pre-presbyopic CL wearers were generally more open to the idea of CLs for presbyopia but reported not having received any information relating to this from their ECP. When considering options for presbyopic vision correction, the majority of the participants indicated that cost, comfort and convenience, in addition to vision, were important factors; however, almost half indicated that comfort, convenience and standard of vision were more important than cost of correction.

Despite the relative negativity in attitude in the aforementioned study, interest in CL wear has been reported among presbyopes. In a survey investigating the opinions and vision correction preferences among 496 presbyopic and pre-presbyopic individuals, 57% of the presbyopic spectacle wearers reported having tried CLs (although this could have been prior to becoming presbyopic) and 67% reported that they would prefer to wear CLs.13 Indeed, the authors concluded that ‘Presbyopes of all refractive errors prefer CL correction, when good vision and comfort can be achieved’ and ‘ECPs should not assume that presbyopia, refractive error, or gender are factors that preclude a patient from being interested in CL wear.’

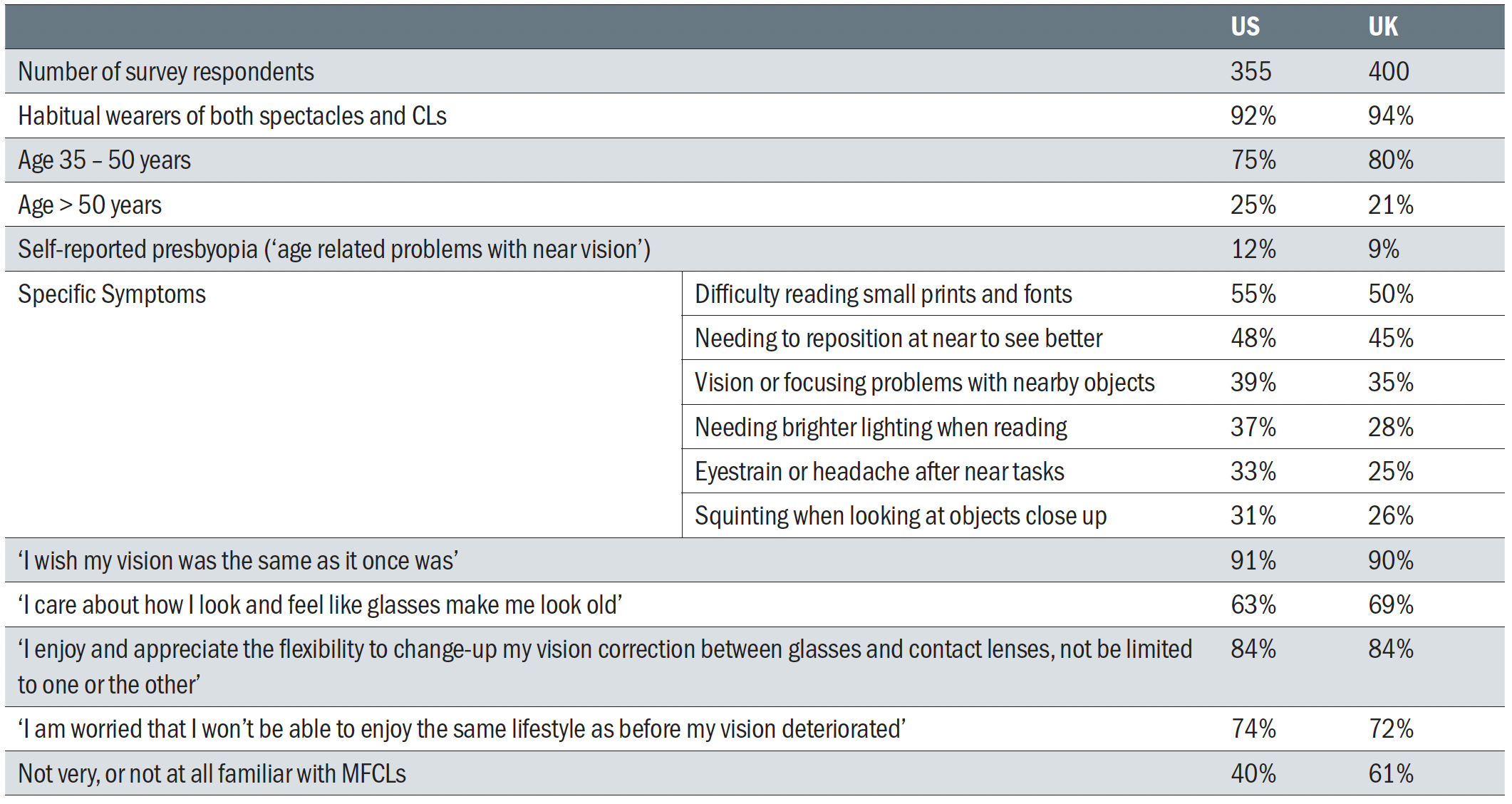

Table 1: Online survey on multifocal benefits (US & UK, 2020) of pre-presbyopic and presbyopic habitual cl wearers on cl wear and beliefs 9

Table 1: Online survey on multifocal benefits (US & UK, 2020) of pre-presbyopic and presbyopic habitual cl wearers on cl wear and beliefs 9

As part of the 2020 Global Multifocal Benefit survey, pre-presbyopic and presbyopic habitual CL wearers in the US and UK completed online surveys regarding their CL wear and beliefs.9 The results are summarised in Table 1. It appears that many presbyopic CL wearers are either not experiencing difficulties with near vision with their lenses, or do not have a clear understanding of what presbyopia is, despite experiencing a number of vision issues known to be associated with decreased accommodative ability. 90% of respondents wished that their vision was the same as it once was and 73% were worried that they wouldn’t be able to enjoy the same lifestyle as before their vision deteriorated.

‘I wish my vision was the same as it once was’

There are only limited reports of the effect of presbyopia and presbyopic vision correction on quality of life (QoL); however, these are factors that are known to have a negative impact on individuals’ day to day activities and self-esteem, compared with younger and emmetropic individuals.14 A more specific approach is to evaluate vision related quality of life (QoV), essentially a subset focusing purely on visual symptoms.15 QoV was incorporated into a recently conducted survey designed to evaluate the QoV with the use of different presbyopic corrections.16 QoV was rated higher by patients whose main tasks were focused at far distance than those with main tasks at intermediate or near distance, regardless of the form of correction worn. The QoV scores were better when respondents were either uncorrected or were wearing reading glasses, implying that a more natural physical appearance was important.

In another recent study, Kandel et al qualitatively explored the refractive error related issues (including presbyopia) that affect people’s QoL.17 The most prominent theme was the participants’ concerns about their cosmetic appearance with glasses, although difficulties carrying out day to day activities and inconveniences of glasses, along with economic implications relating to vision correction were also identified as being important.

Requirements for CL correction for presbyopes

CL correction for presbyopes currently falls into three broad categories: single vision CLs used in conjunction with spectacles for reading, monovision CLs, and MFCLs. The requirements for presbyopic CL correction are clear vision for distance, intermediate and near tasks, the maintenance of binocular vision, and visual comfort throughout the day. Single vision CLs, when worn in conjunction with spectacles for reading are a simple and generally inexpensive option which can provide clear binocular vision at distance and near; however, unless PALs are prescribed for the supplemental spectacles, they are unable to provide correction for intermediate tasks, as reading additions increase. Indeed PALs also have limitations, that can lead to pain in the arms, neck, back and shoulders when viewing monitors or screens at typical working distances18,19 Although monovision CLs can provide clear vision at both distance and near, they too are unable to provide optimal vision for intermediate tasks and contrast sensitivity and stereopsis are reduced.20-23 In order to be successful, MFCL designs need to be able to provide precise central vision under a range of luminance levels, at all distances of interest, while maintaining binocularity. It is therefore recommended that studies to evaluate the performance of MFCLs are conducted in the ‘real-world’, and not based on standard visual acuity measurements made in the consulting room, since these appear to be relatively insensitive predictors of success.22-24 Results from a recently conducted study support offering a trial wear period with MFCLs to allow assessment of performance for common visual tasks.25 Furthermore, MFCLs and monovision correction are able to offer benefits for cosmesis, sporting and outdoor activities, and are able to provide a wider field of view when compared with spectacles.26 They are also able to offer the additional benefit of the wearer not needing to alter their head position for certain visual tasks, for example viewing screens, reading labels and signs when shopping etc.

Overview of current MFCL design

The majority of soft MFCL designs incorporate two or more power ‘zones’ which continually cover the pupillary area. This results in multiple images being superimposed on the retina and the patient’s brain suppresses or ignores the blurred images and chooses the one that is clearest for the visual task being undertaken.27 The term ‘simultaneous vision’ is frequently used to describe MFCL designs; however, since these CLs do not rely on movement on the eye, as is the case with rigid gas permeable alternating or translating designs, the preferred terminology of ‘simultaneous image’ designs is recommended.27 By increasing the depth of focus, the reduction of amplitude of accommodation that occurs with presbyopia, can be counteracted; however, visual performance can be compromised, particularly in conditions of low lighting.28,29

‘I care about how I look and feel like glasses

make me look old’

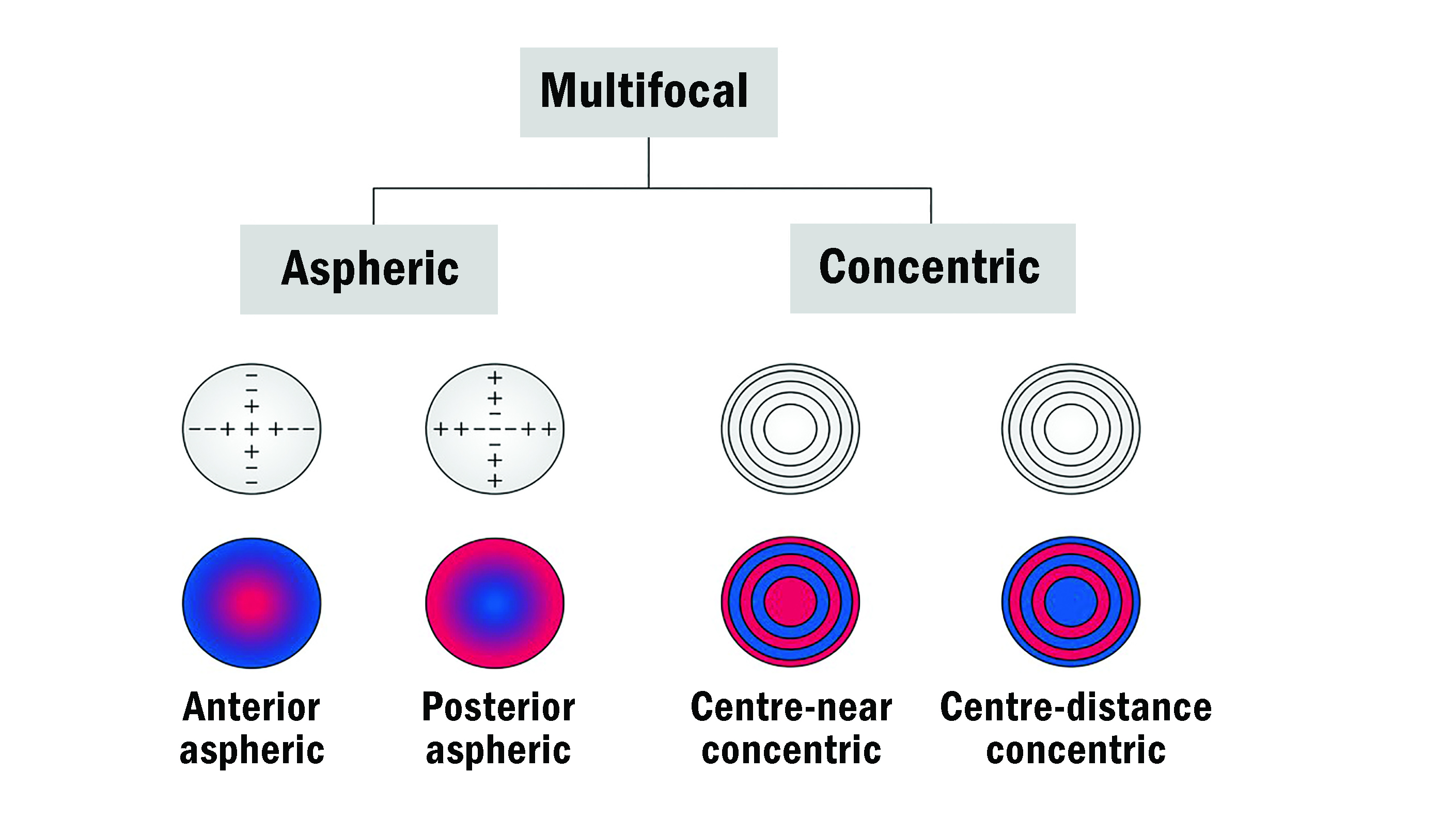

MFCLs can be broadly classified as being spherical, concentric (or annular) or aspheric, and having more than two refractive powers, or a combination of these design features. Concentric MFCL designs usually incorporate a primary viewing zone in the centre of the lens which may be of greater plus power (centre-near) or less plus power (centre-distance), surrounded by concentric rings of near, intermediate or distance powers.30 These lens designs differ from soft bifocal CL designs which only incorporate two distinct powers in different zones, one power for distance vision and one for near vision.30,31 Aspheric designs allow MFCLs to incorporate a progressive, radially symmetric, gradation of power across the optical zone with either greater plus power in the centre of the CL (centre-near) and controlled amounts of negative spherical aberration, or greater plus in the periphery (centre-distance) and controlled amounts of positive spherical aberration.27,31

Figure 1 illustrates examples of concentric and aspheric MFCL designs. In addition, some manufacturers have developed further nuances to these designs; for example the Acuvue Oasys for Presbyopia (Johnson & Johnson Vision) is a centre-distance concentric design that incorporates alternating aspheric zones of power.32

Figure 1: Illustration of examples of concentric and aspheric MFCL designs. In red, areas for near vision and in blue, areas for distance vision (based on Remón et al 2020).30

Figure 1: Illustration of examples of concentric and aspheric MFCL designs. In red, areas for near vision and in blue, areas for distance vision (based on Remón et al 2020).30

CooperVision’s Biofinity multifocal designs incorporate a centre-distance zone which transitions into an aspheric intermediate power surrounded by a spherical near power annulus in the peripheral optic zone, and the centre-near design has a spherical distance power ring in its periphery;33 these lenses can be prescribed contralaterally in order to optimise individual patient requirements.34 Diffractive designs have also been used for MFCLs; however, none are currently available commercially.31

MFCLs are generally available in either two (low and high) or three (low, medium or mid and high) addition powers, and can be further characterised according to their specific power profiles. These allow visualisation and measurement of how the power of individual lens designs vary from the centre to the periphery of the optical zone.35-37 A number of different devices and techniques can be utilised to generate MFCL power profiles that show the relative powers of the central and peripheral regions; these have been summarised recently by Remón et al.30

‘I enjoy and appreciate the flexibility to change-up my vision correction between glasses and contact lenses, not be limited to one or the other’

Unfortunately, simply illustrating the power profiles of MFCLs does not indicate how individual designs will perform when worn. The retinal images formed depend on the combined effects of the MFCL and both the lower (sphere and cylinder) and higher-order aberrations, in particular spherical aberration,38 which has also been shown to vary considerably among individuals,39 and to increase with age.40 This spherical aberration can either improve or degrade performance, dependent on the design of the MFCL.41 Pupil diameter is also known to decrease with increasing age, although light luminance levels have been shown to be the most influential factor affecting pupil size.42 Age was found to be a significant factor, although only between pre-presbyope and established presbyope groups.42 Consequently the same design of MFCL may result in markedly different levels of visual performance among individual wearers.38,43

As referenced earlier, some aspheric MFCLs are manufactured with both centre-near and centre-distance designs and either just one of these (centre-distance) is fitted to both eyes, or both designs are worn contralaterally, which is generally the case for presbyopes requiring higher reading additions.34 As with all MFCLs, it is important to check the manufacturer’s fitting guide when selecting lenses for patients, including recommendations for ocular dominance assessment, as recommended lens selection for a given spectacle prescription does vary between lens designs. Ocular dominance can be assessed using either sensory or motor tests. In sensory testing a +1.00D or +1.50D lens is added first to one eye and then to the other while the patient is viewing a distant target. The patient decides which of the two situations is more comfortable, if this is with the plus lens over the right eye, then the left eye is the dominant one, and vice versa.44,45 Alternatively a motor, or pointing / sighting test can be conducted where the patient initially has both eyes open and either holds one arm out to point at a distant object, or holds a piece of card with a circular hole at its centre and aligns this with a distant target, and the examiner then alternately occludes each eye, with the dominant eye being recorded as the one that continues to see / be aligned with the target when the contralateral eye is covered.44 Unfortunately the sensory and motor tests do not always consistently identify ocular dominance;46 however, a recommended routine would be to conduct the blur test first and then if this cannot be appreciated to conduct a pointing or sighting test.

A more recent approach in MFCL design is to deliberately manipulate the higher order spherical aberrations to extend the depth of focus (EDOF) and this design is now available in the UK and other countries.

Monovision – pros/cons and performance vs MFCLs

Correction of presbyopia with monovision CL wear is common,47 particularly for emerging presbyopes who are habitual ametropic CL wearers. In monovision CL wear, one eye is fully corrected for distance vision and the other eye is enhanced (by incorporating less minus power or more plus power) for near vision. Monovision relies on suppression of the more blurred image, such that is ignored.48,49 Interocular differences of up to + 1.50D have been reported to be acceptable but higher near additions are likely to be less successful. The principal limitation of monovision is the absence of balanced binocular vision which can result in stress on the visual system, diminished depth perception and adverse effects during certain visual tasks, for example navigating steps and driving.50-52 While monovision correction can result in improvements in some health-related quality of life scores for some presbyopes, the ratings remain worse than those for younger emmetropes.53

Although MFCLs are usually able to provide satisfactory visual performance for the majority of visual tasks, light disturbances such as haloes, glare and ghosting are sometimes reported by patients.29,54,55 Visual performance with monovision CL wear is independent of pupil size, and although vision may be compromised with low lighting/contrast,20,56 it has been reported that in most cases the decrement is not as marked as it can be with MFCLs.43,57 However, in a recent study designed to evaluate how different presbyopic CL corrections affect light disturbance, it was reported that adaptation to these phenomena was more effective with MFCL wear when compared to monovision CL wear.58

Summary

Since the number of presbyopes worldwide is rapidly increasing, ECPs are poised to have an exceptional opportunity to prescribe MFCL correction to a large proportion of this population and ECPs’ attitudes towards recommending and prescribing these CLs are changing. Fortunately, there are now different options for MFCL design which are able to provide good vision performance for a wide variety of visual tasks, while maintaining binocularity. Part two of this article will cover prescribing trends for both MFCLs and 1 day CLs, recommendations for prescribing, supplemental fitting tools and patient satisfaction with MFCLs.

- Professor Kathy Dumbleton is a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of California, Berkeley and a Clinical Research Scientist and Consultant. Dr Debbie Laughton is Professional Affairs Manager for CooperVision, EMEA and Dr Jennifer Palombi is Senior Manager, Professional Education & Development for CooperVision in North America.

- This article was funded by CooperVision Inc.

References

- Wolffsohn JS, Davies LN. Presbyopia: Effectiveness of correction strategies. Prog Retin Eye Res 2019;68:124-43.

- Fricke TR, Tahhan N, Resnikoff S, Papas E, Burnett A, Ho SM, Naduvilath T, Naidoo KS. Global Prevalence of Presbyopia and Vision Impairment from Uncorrected Presbyopia: Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Modelling. Ophthalmology 2018;125(10):1492-9.

- Euromonitor International Report: Ageing population and its impact on eyewear. CVI Data on File 2020.

- Worldometer. Population of the United Kingdom (2020 and historical). 2020 [23rd September 2020]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/uk-population/

- Park N. Estimates of the population for the UK. Office for National Statistics; 2019 [23rd September 2020]; Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland

- Census.gov. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019 2019 [23rd September 2020]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-national-detail.html

- Worldometer. Population of the United States (2020 and historical). 2020 [23rd September 2020]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/us-population/

- Alvarez-Peregrina C, Sanchez-Tena MA, Martin M, Villa-Collar C, Povedano-Montero FJ. Multifocal contact lenses: A bibliometric study. J Optom 2020:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2020.07.007.

- CVI data on file. Kubic LLC: Global Multifocal Benefit Online Survey. 2020.

- Morgan PB, Efron N, Woods CA. An international survey of contact lens prescribing for presbyopia. Clinical and Experimental Optometry 2011;94(1):87-92.

- Thite N, Shah U, Mehta J, Jurkus J. Barriers, motivators and enablers for dispensing multifocal contact lenses in Mumbai, India. J Optom 2015;8(1):56-61.

- Hutchins B, Huntjens B. Patients’ attitudes and beliefs to presbyopia and its correction. J Optom 2020:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2020.02.001.

- Rueff EM, Bailey MD. Presbyopic and non-presbyopic contact lens opinions and vision correction preferences. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2017;40(5):323-8.

- Goertz AD, Stewart WC, Burns WR, Stewart JA, Nelson LA. Review of the impact of presbyopia on quality of life in the developing and developed world. Acta Ophthalmol 2014;92(6):497-500.

- McAlinden C, Pesudovs K, Moore JE. The development of an instrument to measure quality of vision: the Quality of Vision (QoV) questionnaire. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010;51(11):5537-45.

- Sivardeen A, McAlinden C, Wolffsohn JS. Presbyopic correction use and its impact on quality of vision symptoms. J Optom 2020;13(1):29-34.

- Kandel H, Khadka J, Goggin M, Pesudovs K. Impact of refractive error on quality of life: a qualitative study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2017;45(7):677-88.

- König M, Haensel C, Jaschinski W. How to place the computer monitor: measurements of vertical zones of clear vision with presbyopic corrections. Clin Exp Optom 2015;98(3):244-53.

- Weidling P, Jaschinski W. The vertical monitor position for presbyopic computer users with progressive lenses: how to reach clear vision and comfortable head posture. Ergonomics 2015;58(11):1813-29.

- Gupta N, Naroo SA, Wolffsohn JS. Visual comparison of multifocal contact lens to monovision. Optom Vis Sci 2009;86(2):E98-105.

- Sivardeen A, Laughton D, Wolffsohn JS. Randomized Crossover Trial of Silicone Hydrogel Presbyopic Contact Lenses. Optom Vis Sci 2016;93(2):141-9.

- Woods J, Woods C, Fonn D. Visual Performance of a Multifocal Contact Lens versus Monovision in Established Presbyopes. Optom Vis Sci 2015;92(2):175-82.

- Woods J, Woods CA, Fonn D. Early symptomatic presbyopes-What correction modality works best? Eye and Contact Lens 2009;35(5):221-6.

- Papas EB, Decenzo-Verbeten T, Fonn D, Holden BA, Kollbaum PS, Situ P, Tan J, Woods C. Utility of short-term evaluation of presbyopic contact lens performance. Eye and Contact Lens 2009;35(3):144-8.

- Woods J, Guthrie SE, Varikooty J, Jones L. Satisfaction of habitual wearers of reusable multifocal lenses when refitted with a daily disposable, silicone hydrogel multifocal lens. In: NCC 2020.

- Jones L, Dumbleton K. Contact Lenses. In: Rosenfield M, Logan N, editors. Optometry: Science, Techniques and Clinical Management: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2nd edition; 2009.

p. 335-55. - Perez-Prados R, Pinero DP, Perez-Cambrodi RJ, Madrid-Costa D. Soft multifocal simultaneous image contact lenses: a review. Clin Exp Optom 2017;100(2):107-27.

- García-Lázaro S, Ferrer-Blasco T, Madrid-Costa D, Albarrán-Diego C, Montés-Micó R. Visual performance of four simultaneous-image multifocal contact lenses under dim and glare conditions. Eye and Contact Lens 2015;41(1):19-24.

- Rajagopalan AS, Bennett ES, Lakshminarayanan V. Visual performance of subjects wearing presbyopic contact lenses. Optom Vis Sci 2006;83(8):611-5.

- Remón L, Pérez-Merino P, Macedo-de-Araújo RJ, Amorim-de-Sousa AI, González-Méijome JM. Bifocal and Multifocal Contact Lenses for Presbyopia and Myopia Control. J Ophthalmol 2020;2020:8067657.

- Bennett ES. Contact lens correction of presbyopia. Clin Exp Optom 2008;91(3):265-78.

- Madrid-Costa D, Ruiz-Alcocer J, García-Lázaro S, Ferrer-Blasco T, Montés-Micó R. Optical power distribution of refractive and aspheric multifocal contact lenses: Effect of pupil size. Contact Lens and Anterior Eye 2015;38(5):317-21.

- Pence NA. Contact Lens Design and Materials: Two New SiHy Lens Options. Contact Lens Spectrum 2011;26(11).

- Sanders E, Wagner H, Reich LN. Visual Acuity and ‘Balanced Progressive’ Simultaneous Vision Multifocal Contact Lenses. Eye & Contact Lens 2008;34(5):293-6.

- Charman WN. Non-surgical treatment options for presbyopia. Expert Review of Ophthalmology 2018;13(4):219-31.

- Kim E, Bakaraju RC, Ehrmann K. Power Profiles of Commercial Multifocal Soft Contact Lenses. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry 2017;94(2):183-96.

- Plainis S, Atchison DA, Charman WN. Power profiles of multifocal contact lenses and their interpretation. Optom Vis Sci 2013;90(10):1066-77.

- Bakaraju RC, Ehrmann K, Ho A, Papas E. Inherent ocular spherical aberration and multifocal contact lens optical performance. Optom Vis Sci 2010;87(12):1009-22.

- Hartwig A, Atchison DA. Analysis of Higher-Order Aberrations in a Large Clinical Population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012;53(12):7862-70.