To begin; a call for action.

‘To keep our patients happy, healthy, and successful with CL wear, we need to think about the person behind the lens.’

Covid-19 has brought around an unprecedented degree of change for contact lens wearers and eye care professionals. We have together climbed a new unknown mountain, responding well by maximising ways to communicate remotely, and adapting our clinics to respect Covid-19 guidance on PPE, hygiene, ventilation and social distancing measures. The journey of digital transformation in healthcare1 including teleoptometry2 is helping us reach the top of the mountain.

Now, as restrictions are easing and we hit the peak, the question is which path do we follow down? Do we head back toward old ways of working or find a new path, with potential unknown terrain (figure 1)?

Figure 1: The Covid-19 journey for contact lens wearers and ECPs. Should we now; (a) return to a familiar path or (b) aim for new heights?

What has gone under the radar, to some degree, is the mental health crisis that has also resulted. In the UK mental health issues have doubled since pre-pandemic levels.3 This means for ECPs, potentially one fifth of the patients who walk through our door could suffer from some level of mental health related issues (figure 2).3,4 According to the World Health Organization (WHO),4 this is globally around double the prevalence of diabetes. A condition we commonly see presenting with ocular manifestation and are more familiar in understanding and discussing advice on lifestyle, healthy living and support pathways.

Figure 2: Around 20% of the patients who walk through our door could suffer from some level of mental health related issues

Figure 2: Around 20% of the patients who walk through our door could suffer from some level of mental health related issues

Firstly, we should explore the behaviours and habits adopted by contact lens wearers during the pandemic to see if we can learn anything that might help us to maximise contact lens performance, to reduce the chance of drop out and, where appropriate, to better understand the care pathways available for additional care. Also, we need to be aware that this post-pandemic new world is very likely to present new contact lens fitting opportunities, given the visual, practical and emotional benefits contact lenses provide. We need to consider the needs of this potentially significant new cohort.

The Current Contact Lens Landscape

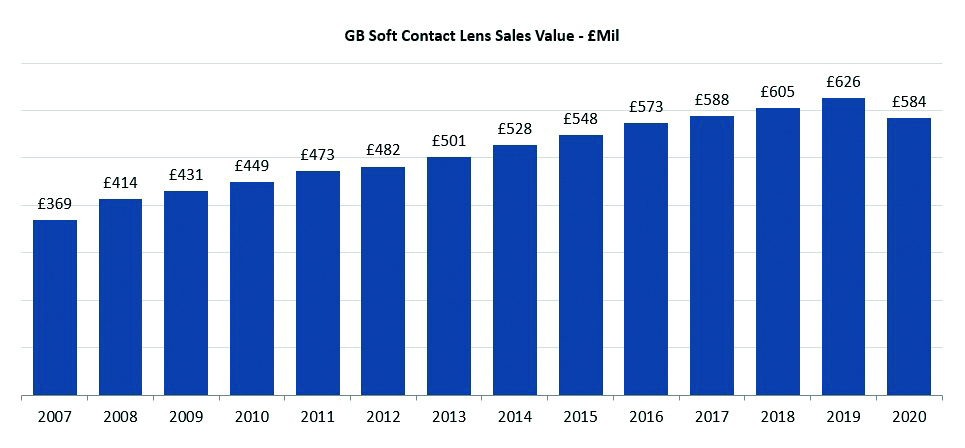

Contact lens sales have shown impressive growth year on year. However, not surprisingly, there was a dip in sales from early 2020 (figure 3). In the UK, this equated to around a £42million reduction in sales compared with 2019, according to GfK data.5

Figure 3: Contact lens market revenues in Great Britain up to the pandemic5

Figure 3: Contact lens market revenues in Great Britain up to the pandemic5

Despite the dip, this overall growth pattern is more robust than in other areas of retail, likely due to the high demand for contact lenses, a relaxation of regulations in response to the pandemic and a greater subscription to home delivery models, all allowing for a continuation of lens supply.

Research into wearing habits has shown a temporary reduction in contact lens usage and yet, even for presbyopes who are generally reported to be more at risk of drop out from lens wear,6 the desire to return to original pre-Covid wear schedules is high, at some 84%.7 In this same study of presbyopic contact lens wearers, 33% reduced their contact lens wear usage and there was only a 5% shift to ceasing lenses wear completely. The main reason cited by patients for reducing their contact lens wear was that they were simply leaving the house less (reported by 70%) rather than what, as ECPs we might expect, issues relating to lens supply restriction or limited access to eye care (reported by just 2%).

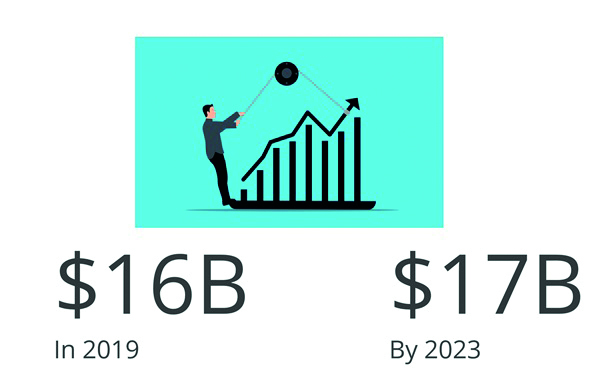

The light at the end of the tunnel, now we are well into the second half of 2021, is that sales trends are now mirroring those of 2019. Indeed, new lens fits in May and June of this year are starting to peak above pre-Covid levels.5 One factor that may be influencing this growth is the widespread frustration with mask wear and steamy spectacles, especially having once experienced the newfound freedoms gained since the last of the lockdowns (figure 4). Globally, contact lens sales are expected to grow from $16 billion as of 2019 to $17 billion by 2023 (figure 5).8

Figure 4: Steamed-up spectacles; a good argument for considering contact lens correction

Figure 4: Steamed-up spectacles; a good argument for considering contact lens correction

Figure 5: Predicted growth in contact lens sales worldwide

Figure 5: Predicted growth in contact lens sales worldwide

The questions that need to be addressed are:

‘Do these new and existing wearers have different needs?’

‘How can ensure that ECPs are the first point of contact for eye care advice?’

‘How do we embrace digital technology as a communication channel and in eye care services?’

Current Challenges to Ocular Comfort

Digital revolution

Digital device and social media usage have both increased at the same time as home working has become the new norm (figure 6). In the US during the pandemic, only 7.7% of adults did not access social media channels and a staggering 78% used Facebook and 50% used Instagram.9 So, how can we ensure ECPs are the first point of contact for eye care advice and how do we embrace digital technology as a communication channel and in eye care services?

Figure 6: Digital screen usage has increased during the pandemic

Figure 6: Digital screen usage has increased during the pandemic

The rise in the use of digital devices is expected to increase the incidence of digital eye strain, which could impact contact lens performance. Indeed, Ganne et al have found an increase in dry eye disease (DED) scores that was proportional to the increase in gadget usage during the pandemic.7 Bahkir et al also reported an increase of approximately 50% in the frequency and intensity of digital eye strain symptoms.10

There have also been reports of binocular vision issues in children11 while others have raised concerns about the potential impact on myopia prevalence, with the term ‘quarantine myopia’ now appearing in the literature to represent the increased risk with increased near work resulting from lockdown.12

One change that has been linked to increased screen usage has been the widespread migration towards online studying, with subsequent behavioural changes and less time being spent outdoors being cited as consequences of this move.13 All of these findings, when considered along with the already known benefits to self-esteem, offer persuasive motivation for fitting children with contact lenses.

The importance for ECPs to offer expert advice about safe digital screen use, such as overall viewing times, the need for regular breaks, blinking habits and the option of tear film supplements as appropriate, is now even more relevant. For this, as readers will by now be well aware, we should follow the TFOS DEWS II guidance.

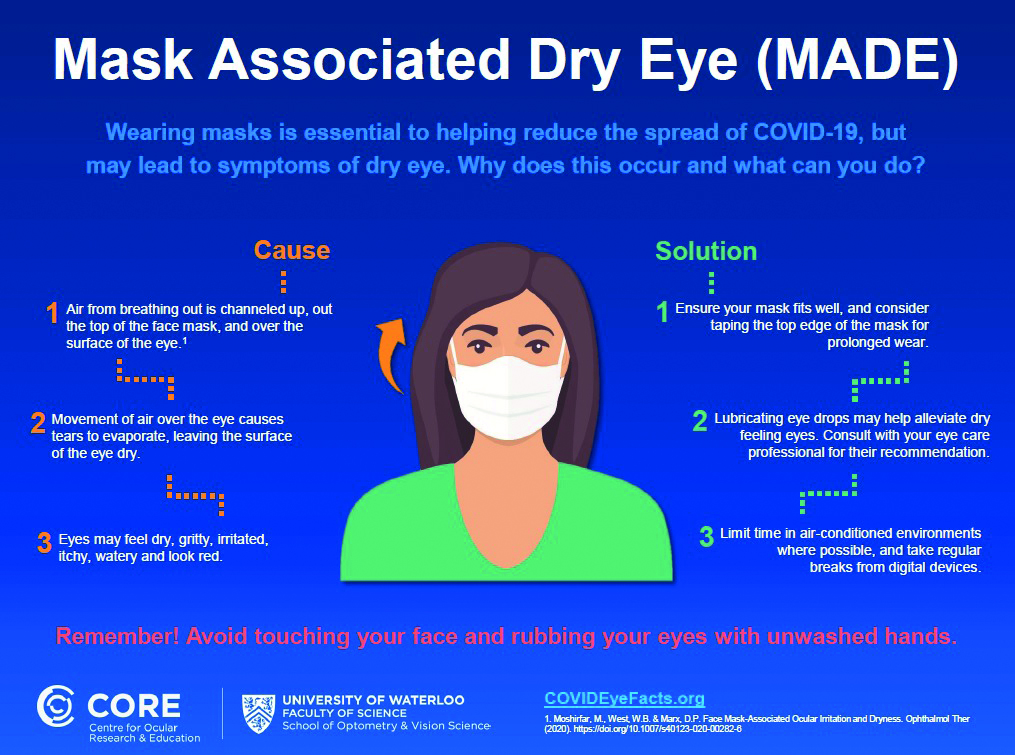

Mask associated dry eye (MADE)

The use of face masks has been associated with increasing the risk of dry eye. The condition is now widely described as mask associated dry eye, or MADE (figure 7).

Figure 7: Infographic of MADE (downloadable from; https://core.uwaterloo.ca/covid-19)

Figure 7: Infographic of MADE (downloadable from; https://core.uwaterloo.ca/covid-19)

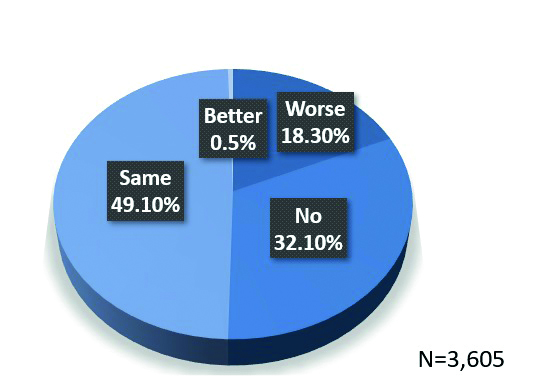

Boccardo has reported that an increase in self-reported symptoms in 18.3% of mask wearers, with risk factors including being female, a history of dry eye and mask wear of more than three hours (figure 8).14 Scalinci et al looked at the impact of mask wear duration and found that, with ‘heavy’ mask usage of at least six hours a day for five days per week, dry eye OSDI scores increased by around five.15 These findings suggest that we should now ask questions about our patients’ mask usage and recognise it as a potential risk factor for dry eye problems. In the UK, around two thirds of adults indicated their intention to continue mask wear in public following the lifting of legal restrictions in July 2021.16 Asking questions regarding mask usage should now become part of our new history and symptoms routine.

Figure 8: Self-reported symptoms related to mask wear14

Figure 8: Self-reported symptoms related to mask wear14

Health and well-being behaviour changes

Spending more time at home while following the Olympics may have motivated some individuals to make more time available for sport and to improve their fitness levels. Others, on the other hand may have chosen to ignore healthier lifestyle opportunities. Remarkably, a link has been established between physical health activity and mental health. A meta-analysis by Gouttebarge et al found that, for current elite athletes, the extent of mental health concerns was 19% for distress and 34% for anxiety/depression. Levels were still high among former elite athletes, with 16% reporting distress and 26% anxiety/depression.17

On a positive note, the Tokyo Olympics has raised awareness of concerns among athletes about mental health. In fact, a data analytics company reported that the coverage of Simone Biles’ decision to withdraw from the Olympics generated more social media attention and interaction than Harry and Meghan’s interview with Oprah Winfrey. On the day Biles pulled out, Google searches related to mental health reached their highest peak in two months.

The media regularly reported how the consumption of take away fast food and alcohol had increased during lockdowns.18 Alcohol consumption is one of many risk factors for dry eye.16 One interesting recent study has highlighted that the impact is very gender specific, with females having significantly greater levels of dry eye symptoms with alcohol consumption, while the males conversely appeared to suffer fewer symptoms with alcohol consumption. This suggests a protective effect on symptomatic dry eye in males with increased alcohol levels.19

Mental Health

An association between mental health and dry eye disease has been reported in the literature, with nearly half (47%) of those with dry eye reporting mental health issues.20 This might, to varying levels, be influenced by the side effects of medications prescribed to these individuals as many such drugs can result in ocular manifestations such as dry eye, reduced accommodation and visual changes.21

History and symptoms considerations

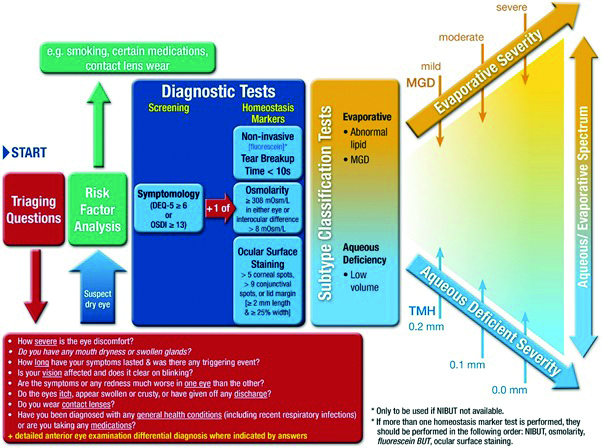

We should all adapt our history and symptoms to reflect the new influences upon ocular surface health. This will then complement well established approaches to assessment, such as that outlined in the TFOS DEWSII report (see figure 9).

Figure 9: A systematic approach to dry eye disease as outlined by the TFOS DEWS II report. Establishing any influence of factors highlighted during the pandemic may help supplement the initial approach to questioning

Figure 9: A systematic approach to dry eye disease as outlined by the TFOS DEWS II report. Establishing any influence of factors highlighted during the pandemic may help supplement the initial approach to questioning

Specific to contact lens wear, we should explore any sub-optimal performance concerns with reference to the principles outlined in the BCLA CLEAR report. The usefulness of asking about comfortable wearing time, comparing current contact lens wearing schedules to desired wearing schedules and any changes in contact lens behaviours are aspects that should not be underestimated.

Mindset and behavioural changes

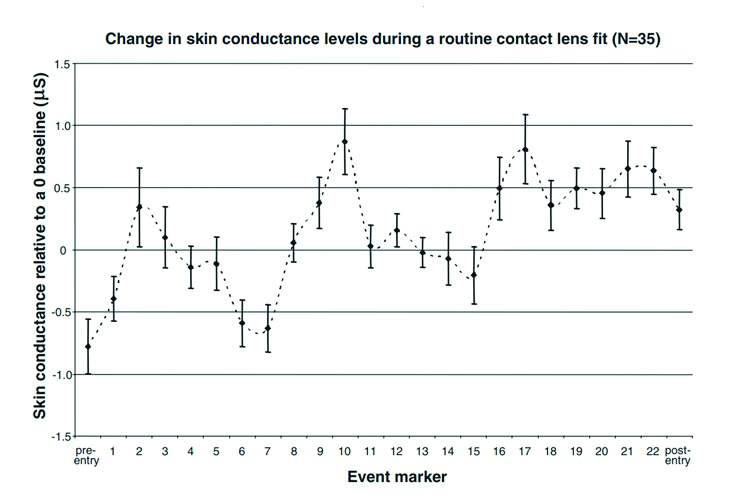

Unprecedented change can easily increase anxiety levels. Vision is often identified as the sense that people most fear losing and, for some people on visiting an ECP, this may evoke negative emotions. Anxiety levels have been found to fluctuate significantly during contact lens fitting, with the highest arousal levels associated with periods of verbal interaction between the patient and ECP (figure 10).22

Figure 10: Skin conductance measured with a polygraph during a contact lens fitting reveals large fluctuations in anxiety levels21

Figure 10: Skin conductance measured with a polygraph during a contact lens fitting reveals large fluctuations in anxiety levels21

In patients with mental health issues, it would seem logical to presume that this anxiety response may be more pronounced. This, therefore, underlines the importance of us considering how we communicate, how we keep our patients calm, and how we might better make use of digital communication channels to reinforce key messages either prior to or after any consultation.

Case study 1

Consider Rebecca (figure 11).

Figure 11: Would you recommend and fit Rebecca with contact lenses?

Figure 11: Would you recommend and fit Rebecca with contact lenses?

Rebecca is a 20-year-old student and is undertaking a full time course delivered online. She is currently spending some 16 hours a day, six days a week at her digital screens. She is known to suffer low grade dry eye disease for which she has never previously received treatment. She does, however, take prescribed medication for anxiety and is also known to suffer confidence issues, which are exacerbated when wearing her glasses.

Would you recommend and fit contact lenses for Rebecca?

Rebecca is likely to represent a typical future contact lens patient and one who has a clear motivation for wearing contact lenses. A prudent approach would be to absolutely require a holistic approach:

- Address her dry eye disease appropriately

- Offer clear advice on her high digital device and ensure this is complied with

- Fit contact lenses as clinically appropriate

Without all three, success is far less likely. A further consideration to maximise the likelihood of fitting success would be to understand more regarding her anxiety. For this we might take inspiration from the ABC model first pioneered by Dr Albert Ellis back in 1957.

ABC Model

The ABC model refers to an acronym based around the following considerations:

- Activating event. Identify and then raise awareness of the triggers that would seem to elicit the emotional response in question, or the ‘alarm’. We could ask them to share a related experience/event that led to anxiety, to draw parallels as to how they may respond to contact lenses, and so then create a safe and reassuring environment and exert a positive influence over their potentially negative attitude.

- Belief. It is important to understand their thoughts behind their existing actions and emotions. ‘What went through your head when this happened?’ They may confirm reasons such as a fear of failure or of being laughed at. Knowing the rationale helps us to adapt our approach. We can best support by relating to their concerns and by encouraging them to mirror our calming behaviour, body language, breathing techniques and practical demonstrations.

- Considerations. Understanding the patient’s responses to the trigger and their subsequent coping mechanisms. For example, if they felt annoyed and sick in response to a trigger, did any subsequent actions help? If, for example, distraction techniques like counting slowly to 10 are known to help, then this can be incorporated into a bespoke customer contact lens fitting journey.

Gauging Mental Health

The WHO defines a person-centred approach as one ‘empowering people to take charge of their own health rather than being passive recipients of services’.

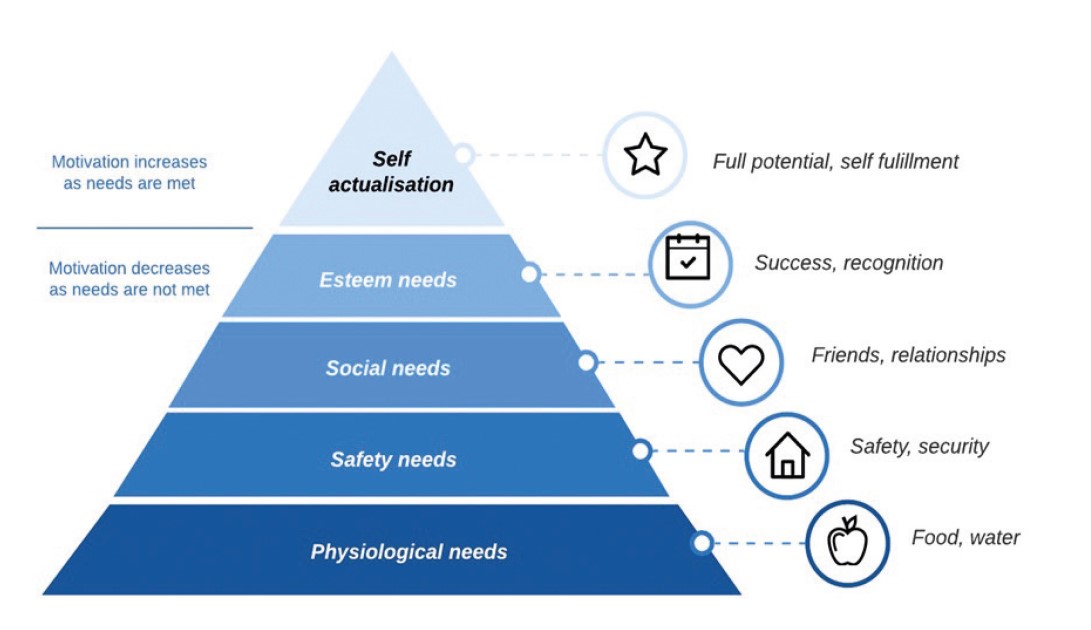

Maslow’s theory of needs23 suggests that everyone is at a different stage of their journey from fulfilling their physiological needs to achieving self-actualisation, understanding more about the person will help us tailor our support (figure 12).

Figure 12: Maslow’s theory of needs23

Figure 12: Maslow’s theory of needs23

One way this might be incorporated into our patient care is through better use of subjective responses and data gathering, whether via questionnaire or the use of patient self-monitoring.

Health-related quality of life questionnaires

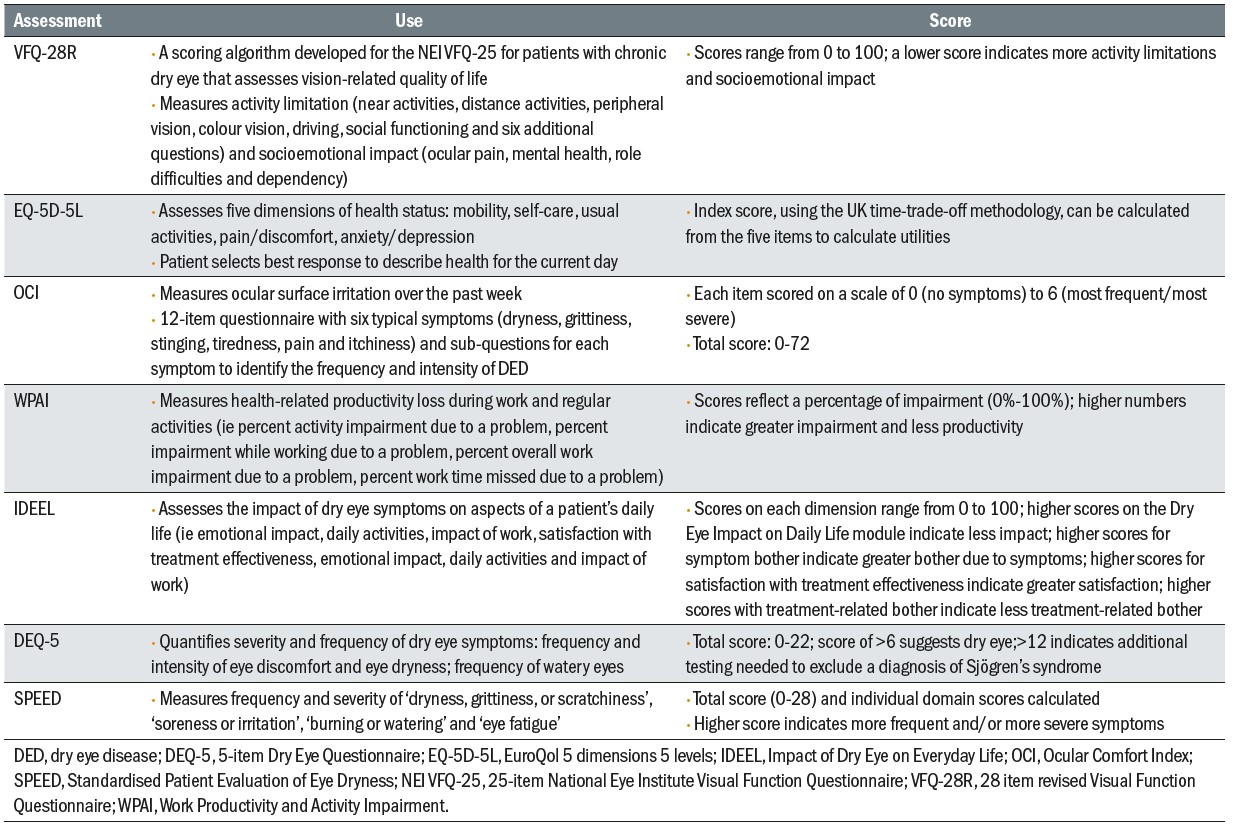

Researchers have established various questionnaires that are available to assess health status, disease severity and any impact on quality of life. These include:

- VFQ-28R

- EQ-5D-5L

- WPAI

- IDEEL

These might be introduced alongside more traditional dry eye questionnaires and so help build a better picture of not just the ocular status, but the overall impact upon physical and mental well-being. Table 1 gives a summary of the use and interpretation of seven useful questionnaires an ECP might find useful.

Table 1: Features of questionnaires to assess disease impact24

Table 1: Features of questionnaires to assess disease impact24

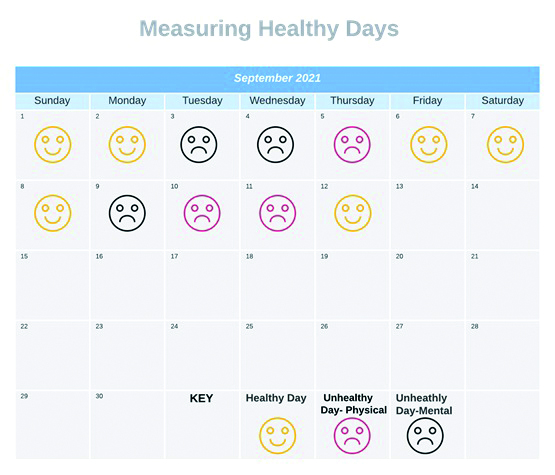

Self-monitoring assessments

Measuring healthy days throughout the month is a simple and effective self-monitoring tool. By recording each day their emotional state (healthy day, unhealthy day-physical or unhealthy day-mental) on a calendar, a patient can help us to build up a better picture of their overall mental status. An example of a simple chart is shown in figure 13.24

Figure 13: A simple self-reporting tool on mental well-being

Figure 13: A simple self-reporting tool on mental well-being

The Role of the ECP

To make a difference to our patients lives, we could do no worse than to introduce one question to our routine: ‘How are you today?’

This may then be usefully followed by active listening, empathy and, where appropriate, follow-up questions. This does not mean we should take on the role of a therapist or start managing patients outside the scope of our expertise. We can very ably support simply by spotting signs and symptoms of mental health concern and then be able to signpost to relevant health care pathways.

Such appraisal of course does help to better recognise any concerns that might influence contact lens wear. Examples of contact lens consultations ‘touch points’ (figure 14) with possible influence upon contact lens performance include the following:

- General observations and behavioural changes. Any negative body language or attention? Do they lack motivation or eye contact? Has this led to non-compliance with contact care regimes or wearing guidance?

- History and symptoms. Open questions will reveal any changes to their daily routines and any impact? How are they feeling today? Is this typical? Any changes to their contact lens habit, usage or any symptoms developed? Questionnaires?

- Risk factors. Are they choosing to spend time alone or long hours doing isolated hobbies? Are they taking any medications? How are their sleep habits? Risk factors for dry eye and contact lens discomfort?

- Ocular and general health. Any co-existing health or ocular conditions? Any ocular manifestations or physical health signs? Is the ocular surface and adnexa healthy?

- Contact lens fit and performance. Any visual impact-refractive changes? Is the lens surface wetting well and clean? Has dry eye or lens spoilage lead to the lens behaviour changing?

- Contact lens related management. Recommend a different contact lens to match their needs? Dry eye or compliance guidance? Remind motivation for lenses?

- Advice and support. Signpost to the Adult Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Programme (see later), and other support networks, health care providers? Encourage setting daily tasks?

Figure 14: Key touch points during a contact lens consultation

Figure 14: Key touch points during a contact lens consultation

These approaches can be adopted across the different eye service delivery methods we now use. For example, if conducting a teleconsultation, although you may not see directly the patient’s body language, you can still pick up on subtle changes in the way they communicate; changes in tone of voice, pace and any loss of interest.

Support Services

A key route to care is the Adult Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Programme, which supports the NHS in implementing National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for people suffering from mental health disorders. It is accessible at www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/adults/iapt. Patients can use this to self-refer (or be referred) to access support services and therapy. The website is well worth reviewing.25

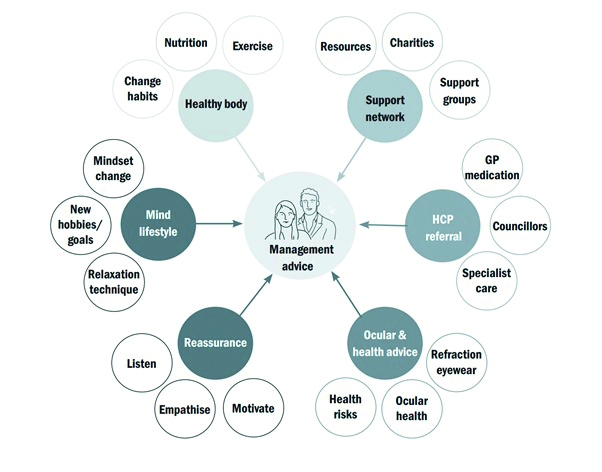

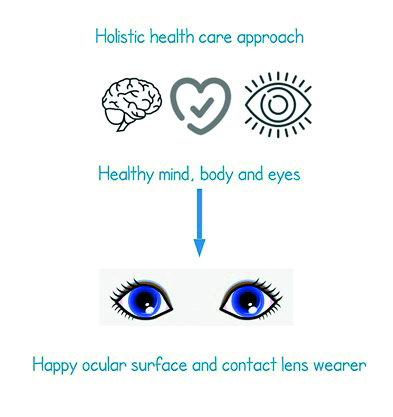

A holistic overview of management, support and advice that might be given to improve health and well-being is summarised in figure 15.

Figure 15: An holistic approach to health

Figure 15: An holistic approach to health

Case Study 2

Consider John (figure 16).

Figure 16: Would you support John returning to contact lens wear and offer useful health and well-being advice?

Figure 16: Would you support John returning to contact lens wear and offer useful health and well-being advice?

John has stopped wearing his contact lenses, saying: ‘I can’t be bothered with them.’ There are no apparent contact lens performance clinical issues that can be identified. John suffers from depression. He is an avid gamer (‘24/7’), used to jog and has previously rejected any offers of support or referral.

Would you support John returning to contact lens wear and offer useful health and well-being advice?

Ideally, gaining commitment to seek support is the goal with John. Small, initial steps might include trying to encourage setting daily self-targets of previously enjoyable hobbies, such as running. This may also prompt motivation to return to contact lens wear. This may then open the door to broader health and support conversations once trust has been established.

Studies have found that the likelihood to return to contact lens wear after drop out is 62%.26 Only a small proportion of dropouts are permanent (12 to 27%, with a pooled drop out of 21.7%)27 with around a 70% of success rate on refitting.28

‘Likelihood to return to contact lens wear after drop out is 62%’26

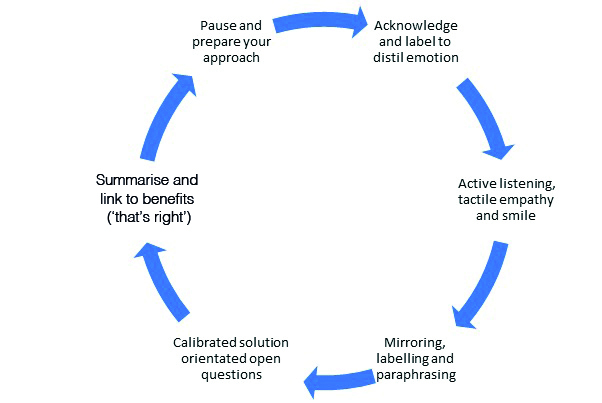

A useful step-wise approach is an adoption of the Voss and Raz model27 of using tactile empathy to change behaviour (figure 17), combined with the author’s own clinical experience.

- First; pause, breath and prepare. Decide on the desired outcome – John appreciating for himself the self-benefits of commencing running again and his previous motivation for contact lenses, to trigger a return to normal habits. Take a calm approach thinking about your body language and communication style. Do you have all the information and insights you need?

- Acknowledge through labelling their emotion; to distil any ‘shut down’ response. ‘I am sorry to hear you no longer have the passion for running or wearing contact lenses.’ The use of pausing allows for processing time, to activate the decision-making part of the brain for new engagement in the conversation.

- Active listening with tactile empathy. You want to ensure they are aware you are listening to them but tactically you are not necessarily agreeing with them. ‘During these challenging times I understand finding the time…’ ‘Remind me what activities you enjoy wearing contact lenses for?’

- Mirroring technique; involves repeating back their own words to reinforce you have listened carefully and focusing their attention more on what you are saying.

- Paraphrasing; includes finding your own way of saying what they have told you, which confirms you have understood what they said. ‘It seems like you miss feeling good after completing a run…’

- Calibrated solution orientated questions; enables you to come to the decision together. ‘What would help you return to running again? How did you feel when wearing contact lenses for running?’

- Summarise and link to the benefits. They need to reach the ‘that’s right’ conclusion. ‘Setting a phone reminder to go for a quick run first thing each morning, to feel great for the day ahead…’ ‘We can provide more contact lenses to help.’

‘How does this sound?’ Silence is powerful to gain their commitment.

Figure 17: The Voss and Raz model27

Figure 17: The Voss and Raz model27

Conclusions and Opportunities

The lifestyle, environmental and emotional changes brought on since the pandemic brings additional reasons to discuss contact lenses. The psychological benefits of contact lenses support the findings of cosmesis been a popular influential factor for contact lenses especially when compared to other refractive correction options.24 The feel-good factor associated with contact lenses could have a positive benefit for boosting self-confidence,

returning to normality and in the management of mental health conditions such as body dysmorphic disorder, depression and those with low self-esteem. They can act as a welcome catalyst to help support active lifestyles and fun time with the newfound freedom provided by the easing of social restrictions.

The current reality is that, alongside a global Covid-19 pandemic, we also have a mental health crisis. This offers opportunities to reflect and evolve as eye care professionals, embracing new technology and modes of practice.

New challenges are arising for our contact lens wearers, with the potential to cause adverse ocular manifestations or sub-optimal contact lens performance, as well as impacting negatively on state of mind. How we care for our contact lens patients is rapidly evolving, as we continue our digital transformation journey and keep pace with supporting wearers’ needs. We can help and go the extra mile for our patients by taking a holistic health care approach to improve ocular health, maximise contact lens performance and wellbeing.

In conclusion, if we want to keep our patients happy and healthy and successful with CL wear, we need to think about the person behind the lens (figure 18).

Figure 18: Conclusion

Figure 18: Conclusion

- Neil Retallic is Global Professional Services Manager for Menicon and an Assessor and Examiner for the College of Optometrists. He is also the President and Chair of the Education Committee for the BCLA.

- The author would like to thank Paul York and Sheena Tanna-Shah for support with this content.

- To find out about the many benefits of BCLA membership, go to www.bcla.org.uk.

References

- Wanat M, et al.. Transformation of primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of healthcare professionals in eight European countries. British Journal of General Practice, 2021 May 11

- Nagra M, et al.. Could telehealth help eye care practitioners adapt contact lens services during the COVID-19 pandemic? Contact Lens & Anterior Eye 43 (2020) 204-207

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest insight. www.ons.gov.uk

- World Health Organisation; https://www.who.int

- GfK data. GB POS Contact Lens Sales (Opticians + Internet); https://www.gfk.com

- Wolffsohn JS, et al. CLEAR - Evidence-based contact lens practice. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye. 2021 Apr;44(2):368-397

- Menicon data on file: Presbyopia survey 2021

- Contact Lenses Report 2020. https://www.statista.com

- Ganne P, et al.. Digital eye strain epidemic amid COVID-19 pandemic - a cross-sectional survey. Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 2021 Aug;28(4):285-292

- Bahkir FA, Grandee SS. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on digital device-related ocular health. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020 Nov;68(11):2378-2383.

- ¹Mohan A, et al. Binocular accommodation and vergence dysfunction in children attending online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic: Digital Eye Strain in Kids (DESK) Study-2. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus, 2021, Jul-Aug;58(4):224-231

- Chang P, et al.. Comparison of myopic progression before, during, and after COVID-19 lockdown. Ophthalmology, 2021 Mar 23: S0161-6420(21)00234-7.

- Wong CW et al. Digital screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: risk for a further myopia boom? American Journal of Ophthalmology, 2021 Mar; 223:333-337

- Boccardo L. Self-reported symptoms of mask-associated dry eye: A survey study of 3,605 people. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye. 2021 Jan 20:101408

- Scalinci SZ, et al.. Prolonged face mask use might worsen dry eye symptoms. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 2021; 69(6):1508-1510

- Wolffsohn JS, et al.. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocular Surface, 2017 Jul;15(3):539-574

- Gouttebarge V, et al.. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Jun;53(11):700-706.

- How the Tokyo Olympics changed the conversation about athletes' mental health. Time Magazine online; https://time.com/6088078/mental-health-olympics-simone-biles

- Magno MS, et al. The relationship between alcohol consumption and dry eye. Ocular Surface, 2021 Jul;21:87-95.

- Hossain P, et al..2021 Patient-reported burden of dry eye disease in the UK: a cross-sectional web-based survey. BMJ Open 2021

- Gherghel D (2020) Ocular side effects of system drugs3-Central nervous system agents. Optician 22 May 2020; 18-22

- Court H, Greenland K, Margrain TH. Evaluating patient anxiety levels during contact lens fitting. Optometry & Vision Science, 2008 Jul;85(7):574-80

- Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 50 (4): 370–96

- Hossain P et al. Patient-reported burden of dry eye disease in the UK: a cross-sectional web-based survey. BMJ Open. 2021, Mar 4;11(3): e039209

- NHS England, Adult Improving Access To Psychological Therapies Programme. Available at; https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/adults/iapt

- Young G, Veys J, Coleman S. A multicentre study of lapsed contact lens wearers. Optom Physiol Opt 2002;22:516–27

- Voss C and Raz T. Never split the difference negotiating as if your life depended on it. Penguin, Random House Business (2016).