Although daily disposable contact lenses are very widely prescribed, on a global basis they still account for a minority of soft lenses prescribed. Even in markets which are very heavy in daily disposable prescribing (such as the UK, Scandinavia and Japan), other daily wear soft lens types still account for around 40% of soft lens fits today.1

These other lens types are generally afforded the descriptor ‘reusable’ or ‘frequent replacement’ to differentiate them from lenses that are applied once and then discarded on removal; this latter category includes extended wear lenses in addition to daily wear.

By virtue of their repeated application, contact lenses worn on a reusable basis for daily wear, most commonly replaced every two weeks or monthly, require appropriate cleaning and storage to provide optimum performance during their use. The rationale for cleaning is two-fold. Contact lenses that are worn on a reusable basis are subject to intrinsic and extrinsic deposits and debris, which in extreme cases can lead to reduced quality of vision; this can be mitigated by ‘rub and rinse’ cleaning.2 Another important reason for lens cleaning is the substantial reduction of microorganisms which occurs with lens rubbing and rinsing. Zhu and co-workers reported the combination of rub and rinse cleaning followed by lens disinfection almost completely removed various types of bacteria from soft lenses, and to a much greater extent than if this cleaning step was eliminated.3

Lens disinfection is generally considered to be the main reason for the use of contact lens storage solutions. While the precise mechanism for contact lens-related infections and inflammatory events is not fully understood, the presence of microorganisms (bacteria, in particular) at the ocular surface is implicated in most or all cases.4-6 As such, minimising the microbial load introduced to the eye with contact lens application is perhaps the key modifiable risk factor for infection and inflammatory events which is under the control of the contact lens wearer7 (and, indirectly through tuition and communication, of the eye care professional (ECP)).

Modern-day solutions to be used with soft contact lenses (both multipurpose solution (MPS) products7,8 and one-step peroxides9) have been shown in laboratory experiments to be effective in most cases in their ability to kill a range of microorganisms. Perhaps more clinically meaningful is epidemiological work, which indicates that contact lens-related corneal infections are more commonplace in wearers who disinfect their lenses less frequently.10 In addition, it is noteworthy that assessments of contact lens infection rates fail to find a difference between daily disposables and reusable lenses used with solutions,11-13 indicating overall strong performance of care regimens when used by lens wearers in real-world conditions.

Lens and care solution combinations

An intriguing issue is the importance of the combination of contact lens material and lens care solution type for overall clinical performance and wearer acceptance. This issue received substantial attention around the turn of the century in what became known as the ‘solution toxicity’ debate. This was triggered by observations of increased corneal fluorescein staining with specific combinations of materials and solutions,14,15 which led to exploration of this response across a wide range of products16 and the adoption of the term solution-induced corneal staining (SICS), to describe an annular pattern of fluorescein staining, with some diffuse staining, of the superficial corneal epithelium.

The latter work specifically explored the response of the ocular surface after two hours of lens wear, although it seemed that the time of the maximum presentation of fluorescein staining varied with solution type, with this particular duration of wear, peak SICS was shown for MPS containing polyhexamethylene biguanide,17 whereas those with polyquaternium-1 and Aldox had their peak response after about 30 minutes.18 Although the discussion at the time centred largely on the impact of the different preservative agents within MPS, more recent research provides evidence that this phenomenon relates to the presence of specific surfactants in contact lens solutions and that fluorescein staining of this form is not indicative of cell death but a transient alteration to the physiology of healthy epithelial cells.19

The SICS debate certainly highlighted the importance of studying the clinical performance of combinations of lens materials and contact lens care systems. The foundation for the formulations of both MPS and peroxide emanates from the pre-silicone hydrogel era and given the great variety of soft contact lens materials now prescribed and the different surface modifications which are also available, it is appropriate that the question of prescribing appropriate pairings of contact lenses and solutions is carefully considered.

Clinical evaluation of lens/solution combinations

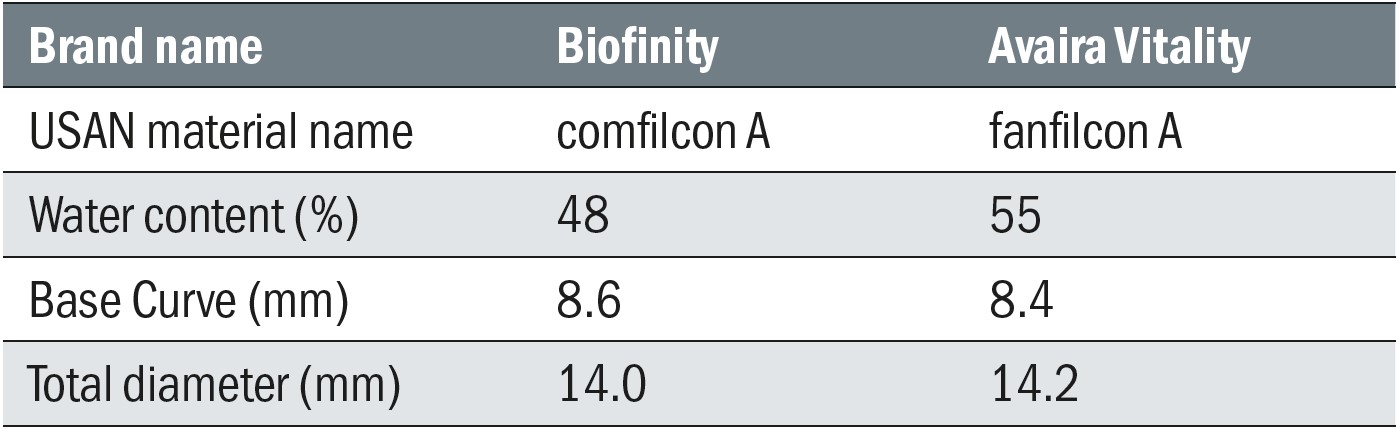

This paper presents information on two recent clinical studies which evaluated silicone hydrogel lens materials and lens care solutions from CooperVision (tables 1 and 2). The first work was a short-term assessment of two lens materials and two lens care solutions after two hours of wear; the second considered the clinical performance and subjective acceptance of six combinations of products and assessed performance in subjects using each for one month.

Table 1: CooperVision silicone hydrogel reusable contact lenses assessed in the clinical studies

Table 1: CooperVision silicone hydrogel reusable contact lenses assessed in the clinical studies

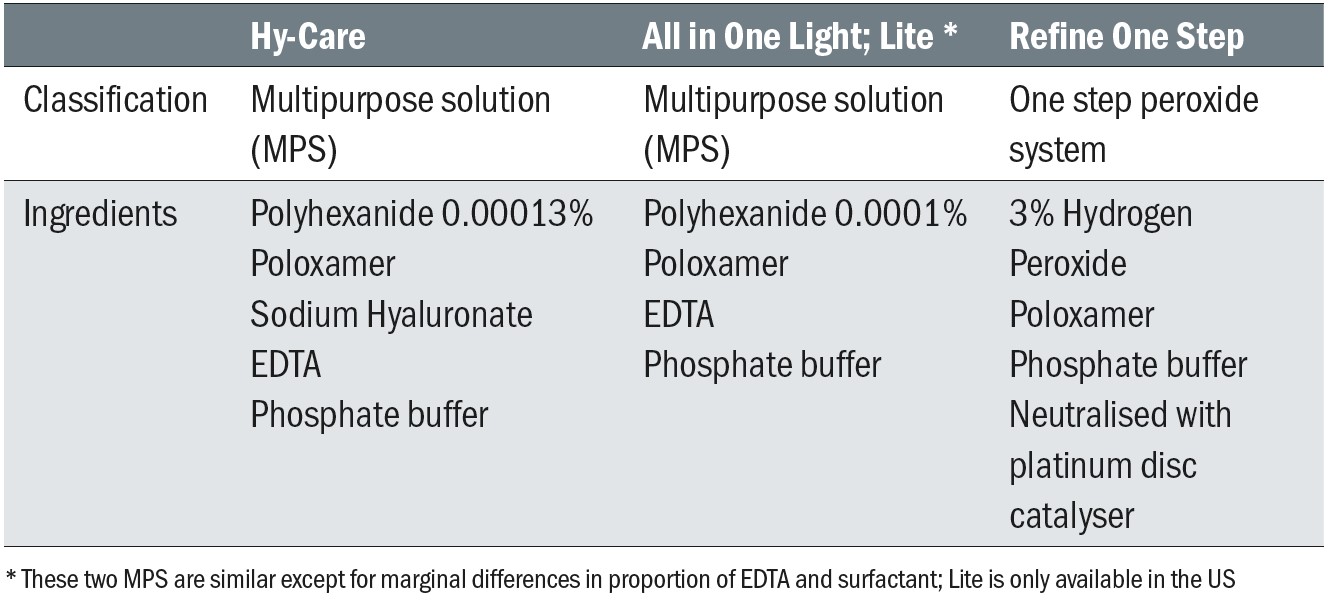

Table 2: CooperVision lens care solutions assessed in clinical studies

Table 2: CooperVision lens care solutions assessed in clinical studies

Short term performance

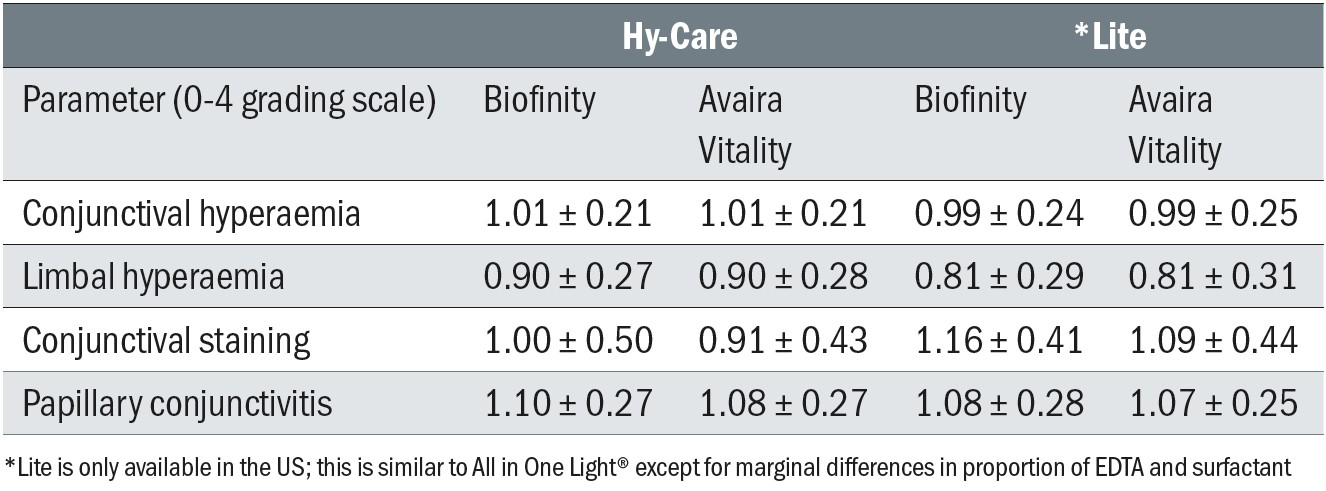

The first clinical study was a randomised, double-masked, contralateral, cross-over study where existing soft contact lens wearers wore Avaira Vitality (fanfilcon A) and Biofinity (comfilcon A) silicone hydrogel lenses, with each lens having been soaked overnight in one of two MPS (Lite and Hy-Care).20 Twenty-eight subjects, (16 females and 12 males) aged 38.9 ± 16.2 years completed the study. Evaluations of biomicroscopy (Efron Grading Scales and percentage corneal staining), subjective scores (comfort, vision, burning/stinging, dryness, grittiness, overall) scored on a 0 (very poor) to 100 (excellent) scale, visual acuity, lens fit and lens surface were conducted two hours after lens application.

For each of the four lens/solution combinations, no differences were seen between the lenses or solutions for lens fit (≥96% acceptable) or visual acuity (high contrast -0.04 logMAR or better and low contrast +0.25 logMAR or better).Lens deposition, debris and wettability were all good (≥93% scored as Grade 0 or 1 in each case at follow-up).There were no differences in subjective scores (all ≥86 units on a 0-100 scale).

Biomicroscopy scores at follow-up were generally similar and all within accepted limits (all < 1.2 units) (Table 3). While there was more conjunctival staining with Lite (p = 0.02) which was also associated with less tarsal conjunctival change (p = 0.05), these differences were less than 0.2 units and not considered clinically significant. The area of corneal staining was low (less than 7% corneal area) with all lens/solution combinations and was lowest (3.1%) with the Lite/fanfilcon A combination and highest (6.3%) with Lite/comfilcon A. Overall, this short-term study indicated good clinical performance for all lens/solution combinations, with negligible SICS after two hours of lens wear. The magnitudes of both the absolute staining levels and the differences between products were modest and well below the threshold considered to be clinically significant.

Table 3: Grades for biomicroscopic signs for each lens/solution combination

Table 3: Grades for biomicroscopic signs for each lens/solution combination

Longer term assessment

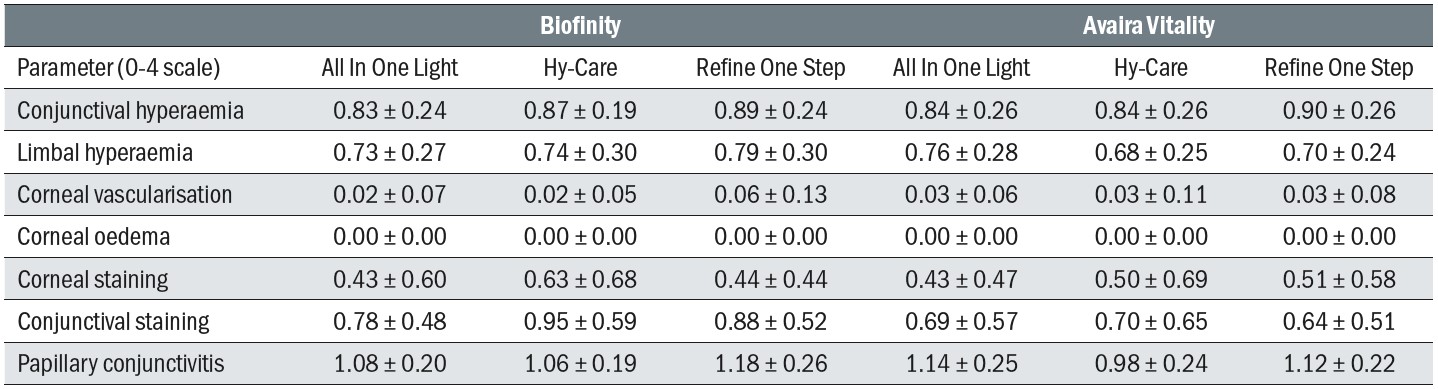

The second clinical study explored the longer-term performance of six lens/solution combinations: Biofinity (comfilcon A) and Avaira Vitality (fanfilcon A) lenses used with Hy-Care, All in One Light and Refine One Step solutions.21 This work was a randomised crossover study, with each recruited subject using all of the six lens/solution combinations for four weeks each. Subjects were examined at the point of each lens dispensing and again after four weeks of use. Lens fit and surface evaluation, visual acuity, biomicroscopy and subjective scores were captured throughout the work, in addition to a series of questions about the experience of each subject with the various products used. Thirty-three subjects (29 females and four males with mean ± standard deviation age of 28.3 ± 7.4 years) were dispensed with study lenses, with 25 completing all the lens/solution combinations.

Lens fits were found to be acceptable at almost all study visits (99.6%) and wearing times were similar for all the lens/solution combinations. There were no meaningful differences between the levels of deposition and debris reported for the lens surfaces. Biomicroscopic scores for the combinations were similar across the six follow-up visits, and while higher grades of conjunctival staining were seen with Biofinity, and higher grades of papillary conjunctivitis seen with Refine One-Step (Table 4), the magnitude of these differences was not considered to be clinically significant. Mean grades for conjunctival staining were all under 1.0 and those for papillary conjunctivitis were all under 1.2.

Table 4: Biomicroscopic scores for all lens/solution combinations after four weeks of use. Scores are mean ± standard deviation

Table 4: Biomicroscopic scores for all lens/solution combinations after four weeks of use. Scores are mean ± standard deviation

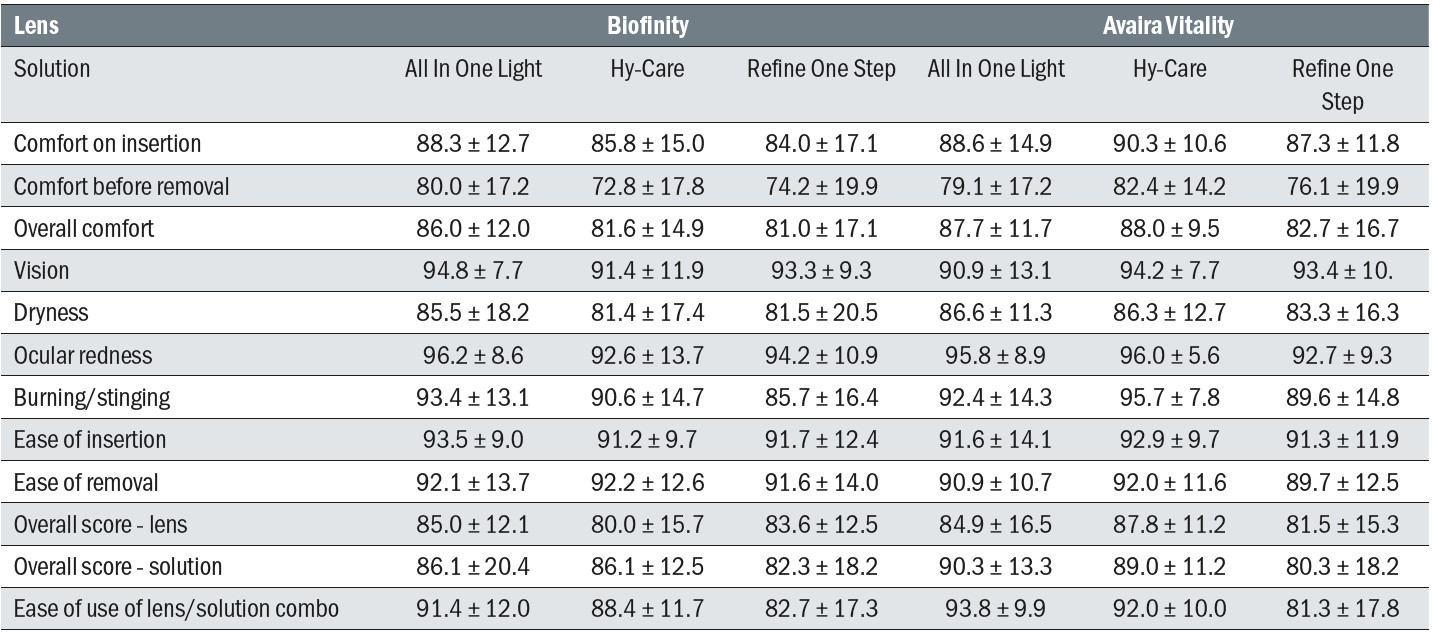

Multiple subjective scores were captured throughout the study (table 5). At the dispensing visits, the only difference noted was a greater value for Biofinity for ‘overall score’ although the magnitude of the difference was small and not considered clinically significant. At the follow-up, scores indicated more burning and stinging with Refine One Step, with this solution also scoring lower for overall score than All in One Light. Refine One Step also scored more poorly for ‘ease of use’ although again, the size of these subjective differences was modest and with the exception of ‘ease of use’, the findings were not considered to be clinically significant.

Table 5: Subjective scores at the follow-up visits. All scores on a 0 to 100 scale. Scores are mean ± standard deviation

Table 5: Subjective scores at the follow-up visits. All scores on a 0 to 100 scale. Scores are mean ± standard deviation

On assessment of the lens surfaces, a longer tear film break-up time was noted for the fanfilcon A than the comfilcon A material at dispensing, but no differences were observed at follow-up. Subjects preferred the bottle and case design for the two MPS (All in One Light and Hy-Care) over the peroxide (Refine One Step).

Fewer than half of subjects reported that (a) their ECP had recommended a care system (41% of subjects) and (b) their ECP discussed care systems at aftercare appointments (35%). Only 6% of subjects reported that their ECP asked to see their lens case at aftercare visits.

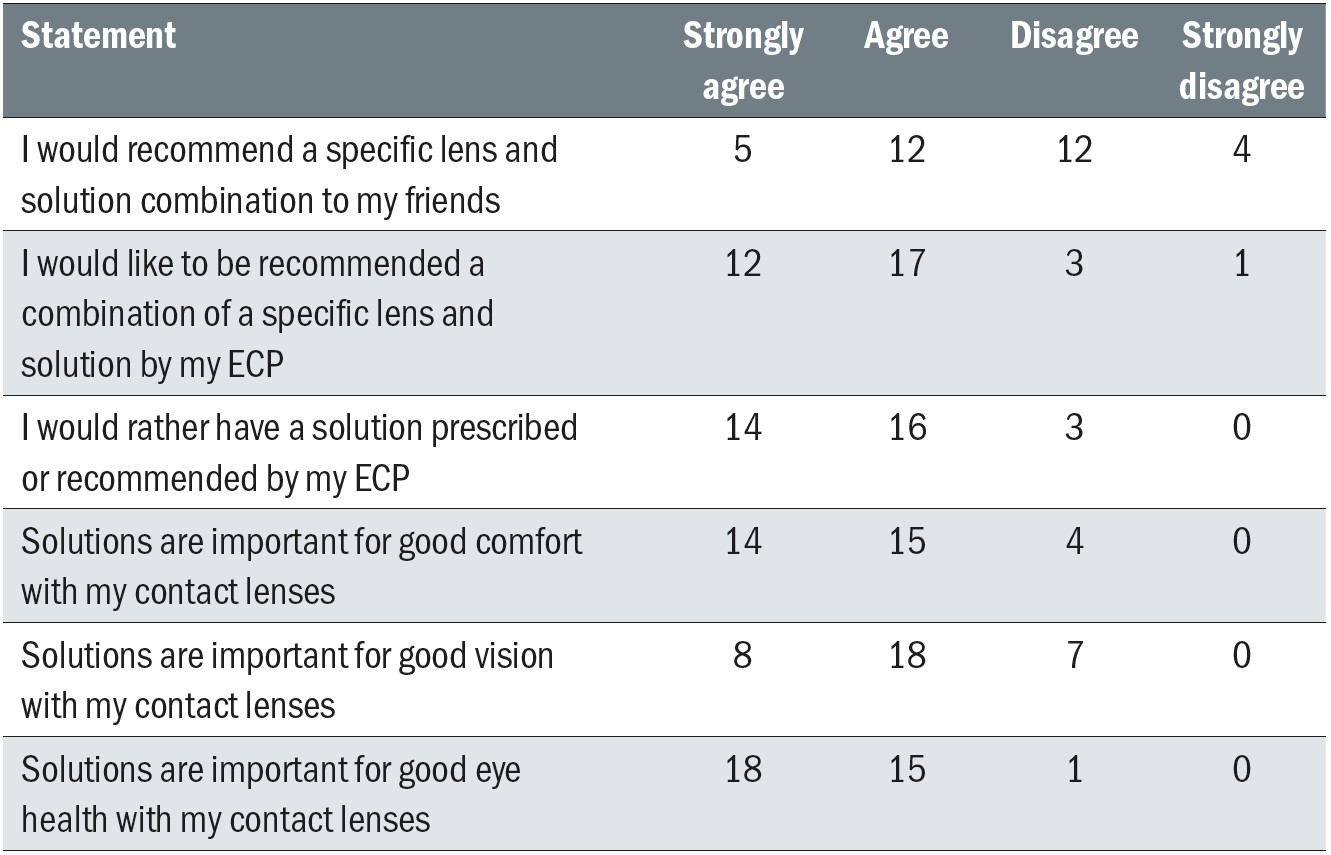

In general, subjects believed that contact lens solutions are important for comfort, vision and eye health, and clear majorities expressed a preference for having their ECP recommend both a specific solution (91% of subjects) and a lens/solution combination (88% of subjects) (Table 6). On the other hand, only about half of subjects (52%) would recommend a lens and solution combination to their friends.

Table 6: Subject responses to questions about contact lens solution prescribing

Table 6: Subject responses to questions about contact lens solution prescribing

Whilst the disinfecting performance of peroxide systems is well regarded, some subjects reported some stinging with the peroxide solutions, a phenomenon which is acknowledged in contact lens practice and which has been reported before.22–24 Some contact lens wearers may report such an observation at an aftercare visit, and if so, this can be readily managed by reinforcing the correct steps for solution use.

Overall, the conclusions of these two recent clinical studies are that the CooperVision reusable silicone hydrogel contact lens (Biofinity and Avaira Vitality) and care system (MPS and one-step peroxide system, All In One Light, Hy-Care and Refine One Step) combinations performed well and were generally well-accepted.

Solutions, compliance and contemporary contact lens use

Contact lens solutions play a fundamental role in minimising the amount of microorganisms reaching the ocular surface during contact lens wear and this, in turn, mitigates the likelihood of contact lens associated adverse events such as microbial keratitis (about two cases per 10,000 contact lens wearers per year11) and other forms of corneal inflammatory events (with symptomatic events reported in 2.5% to 6% of reusable contact lens wearers each year,25 and a lower rate in daily disposable users26).

Given this, the correct use of solutions (and use and care of the associated lens case) is important and indeed, incorrect use is associated with an increase in the likelihood of infections or inflammatory responses. For example, failure to rub and rinse contact lenses prior to disinfection is associated with a 3.5X greater risk of corneal infection,27 whereas not using a suitable disinfecting solution is linked to up to a 55-fold increase.10 Furthermore, ‘topping off’ a solution (ie not fully disposing of any remaining solution in a lens case when lenses are removed in the morning and only adding a small amount of additional solution) has been reported as being associated with a 2.5X chance of infection28 and poor case hygiene has even higher risks (about 4X29). Clearly then, such behaviours should be dissuaded during contact lens aftercare visits and associated good practices — such as appropriate handwashing and drying, and avoiding tap water reaching the ocular surface – need to be constantly encouraged from the initial prescribing of contact lenses.

Opportunities

The current studies and other reported issues around care solution use and compliance provide some clear guidance for future prescribing and patient management. Careful questioning of study participants suggests that they consider that contact lens solutions play an important role in the success of an overall contact lens ‘offering’, in terms of comfort, vision and health. A majority report receiving little information about their solutions and lens cases during the fitting or aftercare process, yet almost all indicate that they would like to be prescribed both a specific solution and an appropriate lens/solution combination.

The message for ECPs is quite clear. Patients would like a combination of lens type and solution to be prescribed and not for the solution to be considered as an unrelated or overlooked product.30 Indeed, formulating a contact lens solution to provide outstanding levels of antimicrobial performance while not negatively impacting the cells of the ocular surface and delivering high levels of wearer comfort is a sophisticated and complex process, and this information can be explained briefly to new patients along with other information about their lens use and care. Reinforcement of solution-related and other compliance steps (especially handwashing and drying, rubbing and rinsing and lens case care31) is not only beneficial in terms of wearers minimising the likelihood of contact lens-associated infections and inflammatory events, but in also optimising vision and comfort and thereby reducing the chance of contact lens drop-outs.32-33

Such strategies need not be solely the responsibility of the ECPs within the practice. Front of house/support staff should also be informed about the importance of prescribing lens/solution combinations and contact lens compliance more generally in order to be able to confidently engage in discussions with new and established lens wearers.

Summary

This article has highlighted the key findings from two recent studies on the importance of the combination of contact lens material and lens care solution type. These works compared the clinical performance of two monthly replacement silicone hydrogel lenses when used with three disinfecting solutions (2 MPS and a one-step peroxide). The two studies demonstrated that both Biofinity and Avaira Vitality performed well and similarly in terms of VA, fit, and subjective impressions. The three lens care products (Refine One Step, Hy-Care and All In One Light) performed well in terms of cleaning, deposition, biomicroscopy and subjective scores, and in the longer term wearing study, all six combinations of lens material and solution types were well accepted and performed well clinically.

- Melanie George, PhD, FBCLA Director Lens Care Research and Development, CooperVision, Inc.

- Fabio Carta, Dip. Optom, FBCLA professional service manager EMEA CooperVision.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on one first published in Optikai Magazine, Hungary. George M and Carta F. Exploring contact lens and care solution combinations. Optikai Magazine, Hungary (June 2021)

References

- Morgan, P, Woods, C, Tranoudis, I et al. International contact lens prescribing in 2020. Contact Lens Spectrum, January 2021: 32–38.

- Gellatly, K, Brennan, N and Efron, N. Visual decrement with deposit accumulation of HEMA contact lenses. American journal of optometry (1988). [online] Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/3265595

- Zhu, H, Bandara, M, Vijay, A et al. Importance of rub and rinse in use of multipurpose contact lens solution. Optom Vis Sci (2011); 88(8): 967–972.

- Fleiszig, S and Evans, D. Pathogenesis of contact lens-associated microbial keratitis. Optom Vis Sci (2010) ; 87(4): 225–232.

- Wu, P, Stapleton, F and Willcox, M. The causes of and cures for contact lens-induced peripheral ulcer. Eye & contact lens (2003); 29(1 Suppl):S63–6; discussion S83–4, S192–4.

- Stapleton F, Dart J, Minassian D. Risk factors with contact lens related suppurative keratitis. CLAO (1993); 19(4): 205-207

- Rosenthal, R, McAnally, C, McNamee, L et al. Broad spectrum antimicrobial activity of a new multi-purpose disinfecting solution. CLAO (2000); 26(3):120–126.

- Rosenthal, R, Henry, C, Stone, R and Schlech, B. Anatomy of a regimen: consideration of multipurpose solutions during non-compliant use. CLAE (2003); 26(1):17–26.

- Kilvington, S. Antimicrobial efficacy of a povidone iodine (PI) and a one-step hydrogen peroxide contact lens disinfection system. CLAE (2004); , 27(4): 209–212.

- Radford, C, Minassian, D and Dart, J. Disposable contact lens use as a risk factor for microbial keratitis’. The British journal of ophthalmology, (1988); 82(11): 1272–1275.

- Stapleton, F, Keay, L, Edwards, K et al. The incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in Australia’. Ophthalmology, (2008); 115(10): 1655–1662.

- Dart, J, Radford, C, Minassian, D et al. Risk Factors for Microbial Keratitis with Contemporary Contact Lenses. Ophthalmology (2008); 115(10): 1647–1654.e3.

- Morgan, P, Efron, N, Hill, E et al. Incidence of keratitis of varying severity among contact lens wearers’. The British journal of ophthalmology, (2005); 89(4): 430–436.

- Jones, L, Jones, D and Houlford, M. (1997) ‘Clinical comparison of three polyhexanide-preserved multi-purpose contact lens solutions’. CLAE (1997); 20(1): 23–30.

- Jones, L, MacDougall, N and Sorbara, L. Asymptomatic corneal staining associated with the use of balafilcon silicone-hydrogel contact lenses disinfected with a polyaminopropyl biguanide-preserved care regimen. Optom Vis Sci (2002); 79(12):753–761.

- Andrasko, G and Ryen, K. A Series of Evaluations of MPS and Silicone Hydrogel Lens Combinations’. Review of Cornea and Contact Lenses, March 2007.

- Garofalo, R, Dassanayake, N, Carey, C et al. Corneal staining and subjective symptoms with multipurpose solutions as a function of time. Eye & contact lens (2005); 31(4): 166–174.

- Kislan, T. (2008) ‘Poster 69: An Evaluation of Corneal Staining With 2 Multipurpose Solutions’. Optometry - Journal of the American Optometric Association, 79(6), p. 330. [online] Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.optm.2008.04.076

- Khan, T, Price, B, Morgan, P et al. Cellular fluorescein hyperfluorescence is dynamin-dependent and increased by Tetronic 1107 treatment’. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, (2018);101: 54–63.

- Mirza, A, Smith, A, George, M and Morgan, P. A clinical investigation of the short-term clinical performance to a range of contact lens and care system combinations. CLAE (2019); 42(6): supplement 1

- CVI data on file 2020. Randomised, open label, crossover, clinical study; FRP lens and solution combinations for 1-month daily wear; n=33 existing soft contact CL wearer

- Josephson, J. E. and Caffery, B. E. Exploring the sting. Journal of the American Optometric Association (1987); 58(4): 288–289.

- McNally, J. Clinical aspects of topical application of dilute hydrogen peroxide solutions. CLAO (1990); 16(1 Suppl): S46–51; discussion S51–2.

- Paugh, J, Brennan, N and Efron, N. Ocular response to hydrogen peroxide’. American journal of optometry and physiological optics, (1988); 65(2): 91–98.

- Szczotka-Flynn, L, Jiang, Y, Raghupathy, S et al. Corneal inflammatory events with daily silicone hydrogel lens wear’. Optom Vis Sci (2014); 91(1): 3–12.

- Chalmers, R, Keay, L, McNally, J and Kern, J. Multicenter case-control study of the role of lens materials and care products on the development of corneal infiltrates. Optom Vis Sc9 (2012); 89(3):316–325.

- Radford, C, Bacon, A, Dart, J and Minassian, D. Risk factors for acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens users: a case-control study. BMJ (1995); 310(6994): 1567–1570.

- Saw, S, Ooi, P, Tan, D et al. Risk factors for contact lens-related fusarium keratitis: a case-control study in Singapore’. Archives of ophthalmology, (2007); 125(5): 611–617.

- Houang, E, Lam, D, Fan, D and Seal, D. Microbial keratitis in Hong Kong: relationship to climate, environment and contact-lens disinfection. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (2001);95(4): 361–367.

- Morgan, P, Efron, N, Toshida, H and Nichols, J. An international analysis of contact lens compliance. CLAE (2011); 34(5): 223–228.

- Dumbleton, K, Woods, C, Jones, L and Fonn, D. The impact of contemporary contact lenses on contact lens discontinuation’. Eye & contact lens (2013); 39(1): 93–99.

- Sulley, A, Young, G and Hunt, C. Factors in the success of new contact lens wearers’. CLAE (2017); 40(1): 15–24

- CVI data on file 2020. Randomised, open label, crossover clinical study; n=34 existing soft CL wearers; baseline questionnaire