An understanding of contact lens practice is fundamental to the ophthalmic dispensing process since contact lenses are an option that should be offered to spectacle wearers as part of the process of gaining valid informed consent when dispensing. Eye care practitioners (ECPs) often find themselves responsible or accountable for the supply of lenses to patients they have not themselves fitted, so an understanding of contact lens terminology, fitting procedures and the law are essential for dispensing opticians as well as contact lens opticians and optometrists. This article will take a look at the basics of contact lenses and the regulations relating to their supply

Background

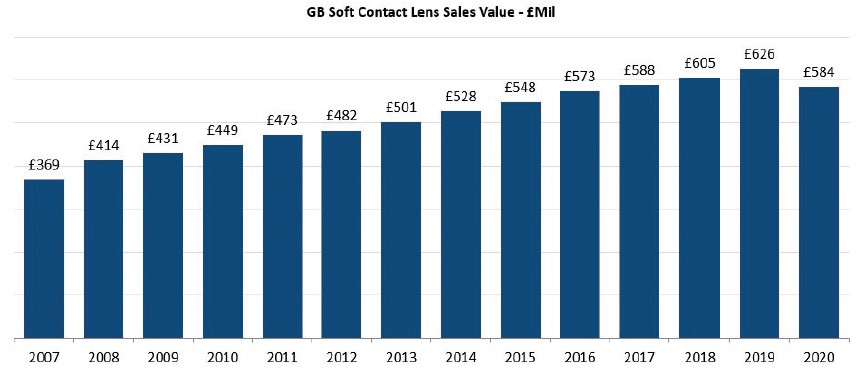

Contact lenses represent about one sixth of the UK optical market by value and are an important and significant income stream for the majority of UK practices (figure 1). At approximately four million people, contact lens wearers represent around 6% of the UK population and around 10% of those that require sight correction. Although a significant proportion of sales have migrated online, community practices in the UK have been much less badly affected by this competition than optical practices in comparable developed nations.

Figure 1: Contact lens market revenues in Great Britain up to the pandemic (GfK data. GB POS Contact Lens

Figure 1: Contact lens market revenues in Great Britain up to the pandemic (GfK data. GB POS Contact Lens

While compliance with regulations may contribute to this, and prevents players such as Amazon entering the UK market, it is also because the predominant business model for the supply of daily (single use) and monthly (daily wear reusable) disposable lenses has been, since the 1980s, advance payment by direct debit, usually accompanied by direct to patient home delivery. While this has helped opticians preserve their market share, or at least slow the decline, it also requires a firm grasp of the law and regulations relating to both contact lens fitting and to contact lens supply if practitioners are to avoid falling foul of the rules.

The Opticians Act

Part 4 of the Opticians Act 1989 (as amended 2005) relates to ‘restrictions on testing of sight, fitting of contact lenses, sale and supply of optical appliances and use of titles and descriptions’ and is the most important part of the Act for ECPs to have a thorough knowledge and understanding of. A failure to evaluate a situation appropriately could result in a failure to apply the law and regulations correctly and may result in the ECP finding themselves subject to fitness to practice proceedings.

The Opticians Act may be accessed at https://www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/opticians_act.cfm.

Contact Lenses Fitting

Section 25 of the Act relates to the fitting of contact lenses. The principle actions that are mandated are:

- Contact lenses may only be fitted by a person registered as a dispensing optician, optometrist, medical practitioner, or an optical or medical student under supervision. The Act does not make clear that when referring to dispensing opticians it may (or may not) be referring to those on the specialist register of contact lens opticians . However, the Contact Lens Qualifications Rules 1988 do make clear who may fit contact lenses, and like all GOC Rules and Regulations https://www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation/rules_and_regulations.cfm must be read in conjunction with the Act.

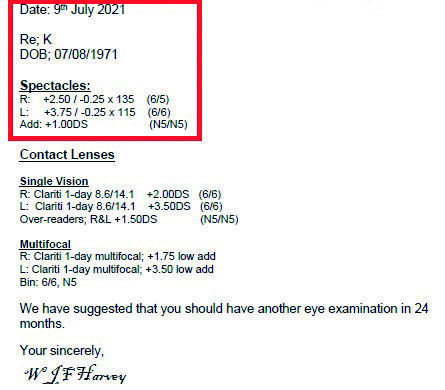

- At the point where fitting begins the patient must have a valid sight test prescription not more than two years old, or within the recall (re-examination) period specified if sooner (figure 2). Note that a ‘prescription’ refers to the result of a ‘sight test’, whereas a ‘specification’ refers to the result of ‘fitting a contact lens’.

- A person fitting lenses who is not entitled to do so ‘shall be liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale’. On March 13, 2015 the level 5 fine limit of £5,000 was removed and is now unlimited. The low fine level had become so insignificant as to have no deterrent effect and be considered little more than an operating cost to suppliers who routinely break the law.

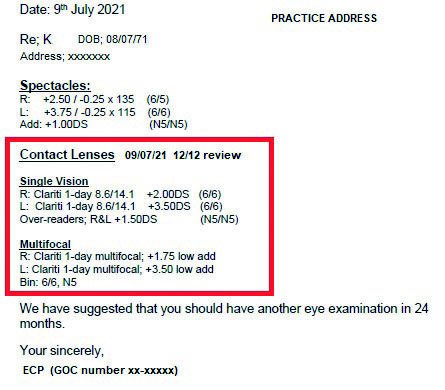

- At the end of the fitting process, which can take several visits, a contact lens specification must be issued, which should include an expiry date and be ‘sufficient to enable the lens to be replicated’ unless, of course, the fitter deems the patient unsuited to contact lenses and discontinues wear.

- Section 25 (subsection(5)(b)) also requires the person who fits the contact lenses to ‘provide the individual with instructions and information on the care, wearing, treatment, cleaning and maintenance of the lens.’ This makes it clear that the fitting practitioner is accountable for the final part of the fitting process commonly known as a ‘teach’ or ‘I&R’ (insertion and removal) when the patient is taught how to apply, remove, and care for their lenses. I&R is therefore a restricted function in law and should only be carried out when there is a qualified registrant on the premises and able to intervene.

Figure 2: For contact kens fitting to commence, the patient must present a sight test prescription not more than two years old, or within the recall period specified if sooner

Figure 2: For contact kens fitting to commence, the patient must present a sight test prescription not more than two years old, or within the recall period specified if sooner

The GOC Contact Lens Qualifications Rules 1988 make clear who can legally fit contact lenses. Although the Rules on the Fitting of Contact Lenses 1985, and the Opticians Act 1989 both appear to say that ordinary dispensing opticians can fit lenses (as was the case prior to 1985) the 1988 Rules clarify that only those DOs who were certified in 1988 as qualified through experience – ‘grand fathered’ to the new system by fitting 150 patients over three years – were subsequently able to join the register of contact lens opticians. So, contact lenses can only be fitted by optometrists, medical practitioners, dispensing contact lens opticians, or students of each of these professions on a recognised course of study.

Following a sight test the ECP responsible for fitting the patient with contact lenses will ask questions, perform a number of tests, and give instructions to the patient. According to ABDO’s advice and guidance fitting should include:

- History and symptoms including general and ocular health, previous contact lens wear, history of any allergies, systemic disease, and occupational and lifestyle requirements.

- Gaining valid consent to proceed including providing advice on the risks and complications of contact lens wear, relevant available lens types, advantages and disadvantages, relative risks, costs, etc, so that the patient can make an informed choice.

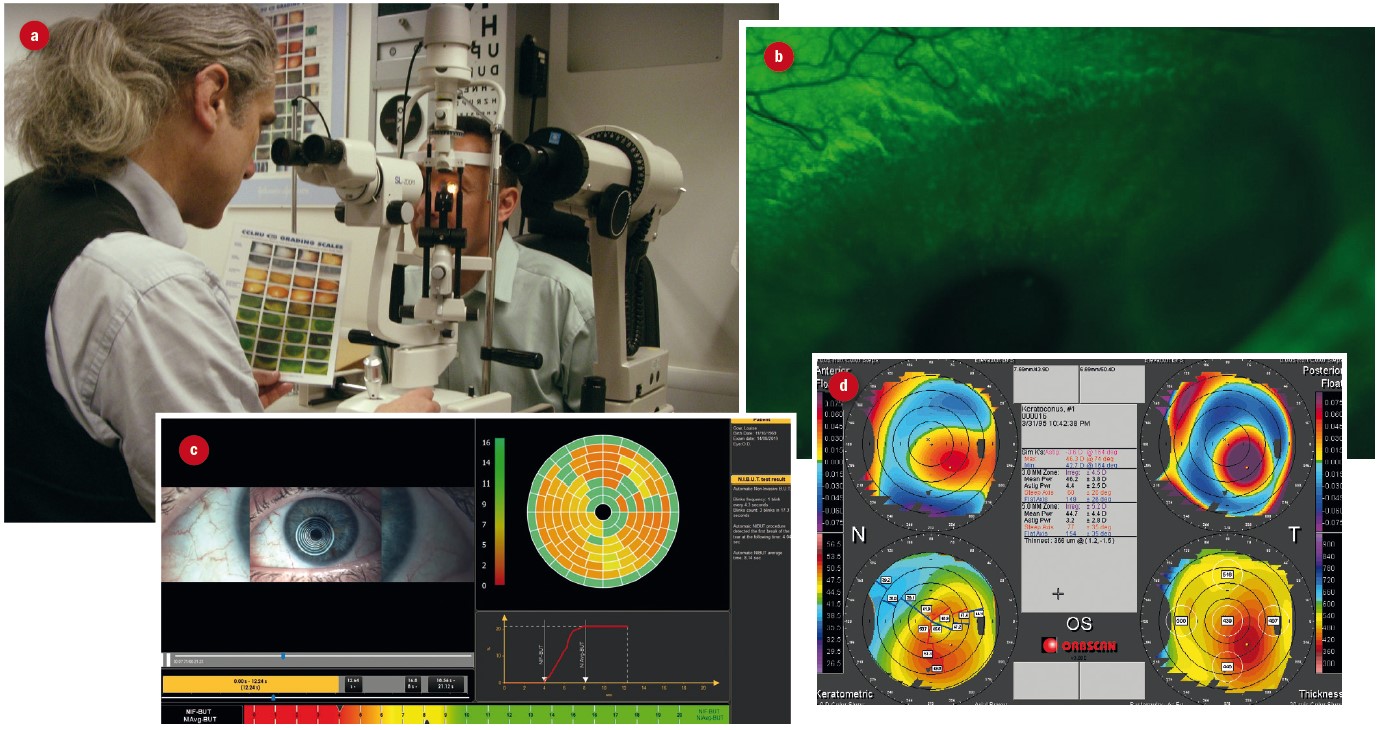

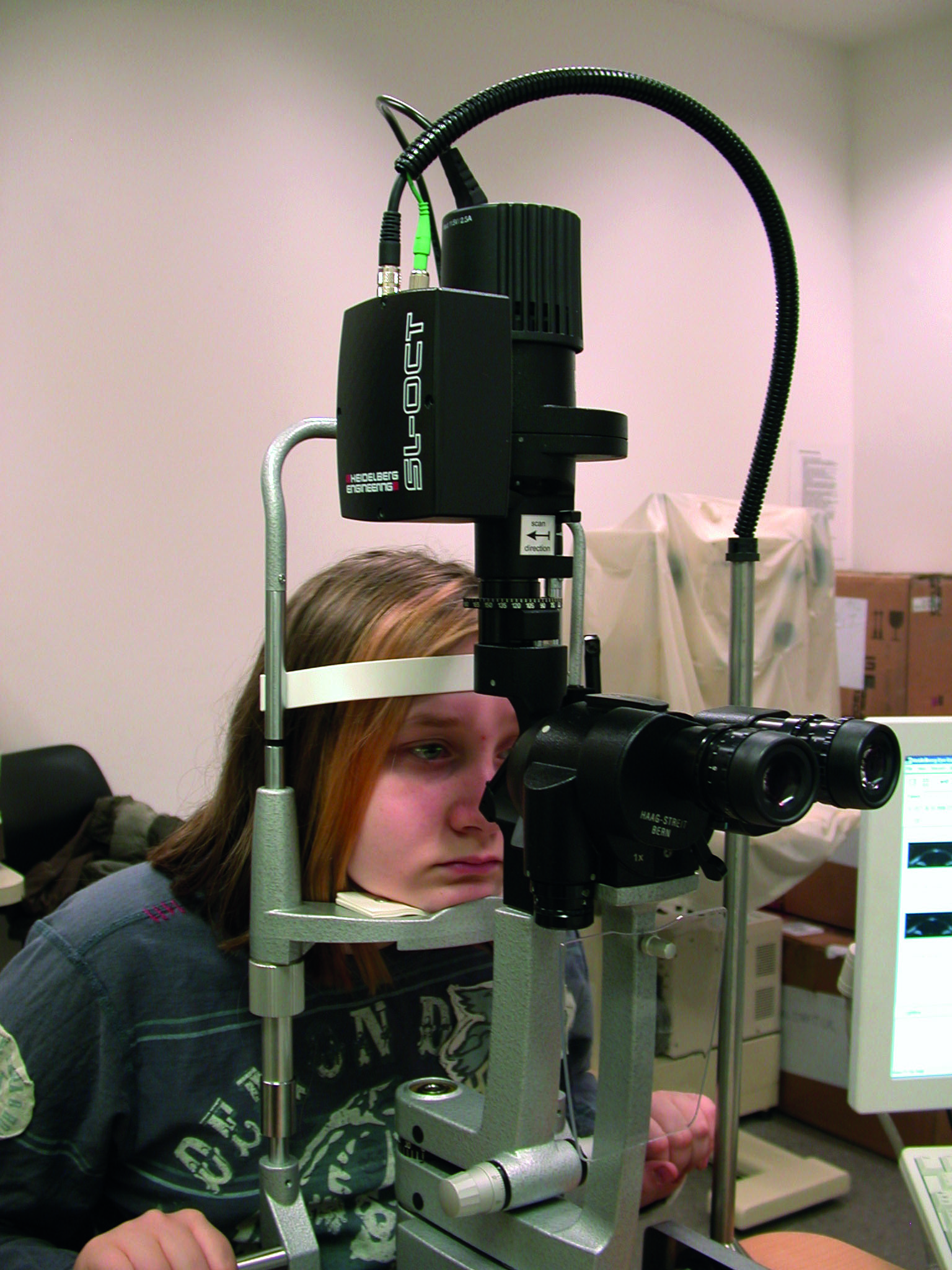

- Anterior eye assessment including slit lamp bio-microscopy, use of diagnostic stains, assessment of tear film and typically keratometry or topography (figure 3).

- Instruction and assessment of handling and hygiene. Patients who are not able to safely handle or maintain lenses should be advised that it is in their best interests not to proceed with the fitting.

- Educating the patient on signs and symptoms that require seeking immediate professional advice.

- Issuing a contact lens specification once fitting has been completed (figure 4). It remains the practitioner’s decision to determine when the fitting process is complete as this can vary between patients and complexity of contact lens design. This process is typically complete at the first aftercare after a week or two, and will ‘generally’ not be more than three months, but the practitioner must be confident the contact lenses will not compromise ocular health.

Figure 3: Elements of anterior eye assessment; (a) slit-lamp examination, (b) use of dyes to assess staining, (c) tear film break-up time, (d) topography

Figure 3: Elements of anterior eye assessment; (a) slit-lamp examination, (b) use of dyes to assess staining, (c) tear film break-up time, (d) topography

Figure 4: Simulated contact lens specification

Figure 4: Simulated contact lens specification

Consent, History & Symptoms

Valid consent must be obtained before the patient can be fitted with contact lenses and is gained as part of a process of two-way communication that takes into account the patient’s history and symptoms, including lifestyle factors, and their attitude to risk. GOC Standard 3 (obtain valid consent) requires ECPs to explain what they are going to do and ensure that patients are aware of any risks and options in terms of examination, treatment, and sale or supply of optical appliances.1

What is offered to the patient will depend upon many factors including their sight test prescription, which may preclude certain options. How often they intend to wear lenses is also an important factor – traditional lenses that take relatively longer to adapt to and build up wearing time are largely unsuitable for occasional use unless only for short periods of time of no more than a few hours.

Data on the relative risks of contact lenses are somewhat in need of updating given the wholesale move towards daily disposability in many markets, and the resurgence of extended and overnight wear modalities, such as orthokeratology. However, there is no reason to doubt the work of Dart and various collaborators in the 1990s, who reported that contact lens wearers are up to 80 times more likely to contract sight threatening keratitis than spectacle wearers, and are even six times more likely to develop microbial keratitis compared to patients with pre-existing ocular trauma (figure 5). Compared to gas permeable lenses soft daily wear and extended wear lenses increase the risk by 3.6x and 20-fold respectively.

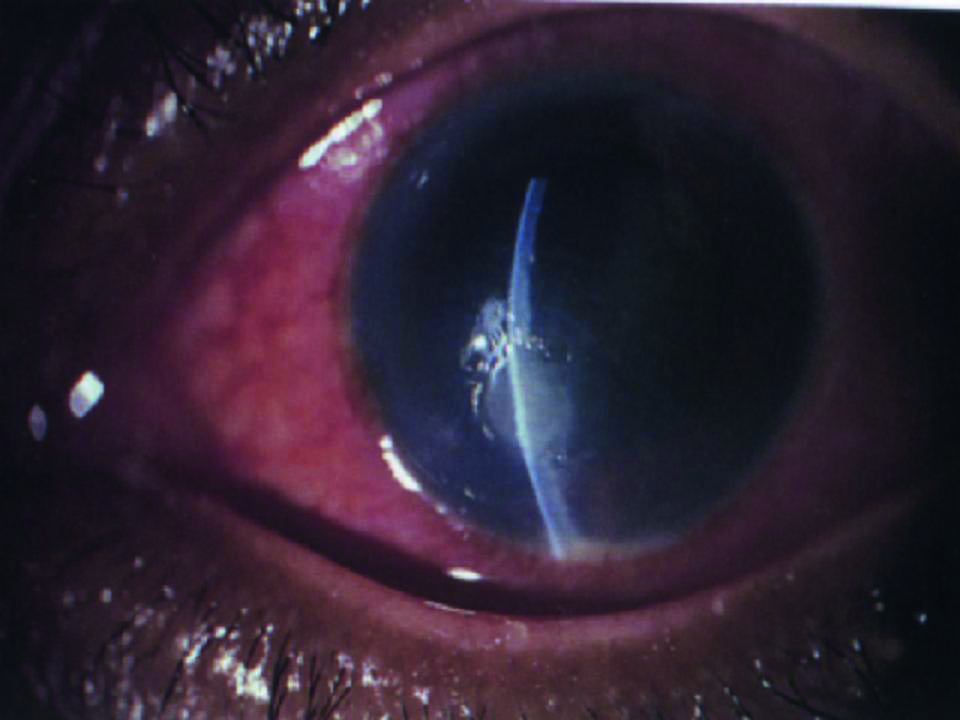

Figure 5: Severe microbial keratitis

Figure 5: Severe microbial keratitis

GOC Standards of Practice require registrants to keep up to date. Free access to research evidence of the risks of wearing contact lenses is easily achieved through the American PubMed and National Institutes for Health websites and their European sister organisations. Stapleton and Dart’s article2 (may be accessed at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/8261602) leads, through the ‘citations and impact’ link, to over 70 related articles and is a useful to a comprehensive overview of the risks of contact lens wear.

Nevertheless, 80 times a very small risk remains a small risk and contact lenses are a safe means of sight correction and are especially safe when patients comply with the wearing schedule and hygiene regime that has been personally advised. The importance of compliance, what constitutes an emergency and what to do about it should be given in writing to all patients at first fitting and at regular intervals. Patients could also be directed to www.loveyourlenses.com a GOC funded website that aims to inform patients on the risks and benefits of contact lenses and the importance of regularly seeing a contact lens practitioner.

There is a debate whether there is a duty to mention contact lenses to all patients during a sight test, or during dispensing. It is very rare for a patient these days to be completely unsuited to contact lenses and patients should be made aware of the benefits of lenses to them as part of the process of giving informed choice. Just because a patient reaches their mid-forties without contact lenses it should not be assumed that they will not be interested once they have become presbyopic – multifocal contact lenses, for example, offer clear vision at all distances in all directions of gaze, which may be seen as an advantage over multifocal spectacles which do not.

A similar debate concerns whether or not practitioners should also mention refractive surgery as an option. Certainly, if asked, practitioners should be able to give an informed opinion and understand the relative risks. Refractive surgery carries a lower risk of sight threatening microbial keratitis but a higher risk of resulting in visual acuity that is lower than the patient experiences with their spectacles or might be achieved with contact lenses especially at night when haze and glare are significant problems for a small minority of patients.

Case Study – Consent

Patient A had successfully worn monthly disposable 55% hydrogel lenses for around 10 years although he was only able to wear them comfortably for around nine or 10 hours per day. When attending a check-up, he saw a different practitioner to normal and was offered silicone hydrogel lenses as a means of improving oxygen transmission and hopefully safely increasing comfortable wearing times. The patient took up the offer and was delighted with the results and signed up on a new direct debit scheme as a result. Attending an aftercare check-up on the silicone hydrogel lenses the patient asked his usual practitioner how long his new lenses had been available for and was dismayed to learn that they had been available for all the time he had been a contact lens wearer and that he had never been offered them.

The ECP was sanctioned by the GOC fitness to practice hearing for ‘forced selling’, that is failing to give a patient an informed choice. Forced selling occurs in many forms – pushing patients into products they do not really need because they seem to be able to afford it, taking the easy option of leaving the patient in what they have had previously, or simply prejudging that the patient will not want or cannot afford a better quality optical appliance.

Case Study – Gillick Competence

A special case of consent concerns Gillick competence3,4 which refers to the ability of a child under-16 (the age at which capacity to consent can be assumed) to consent to an optical service without parental involvement. A competent child can sign their own GOS forms, decide on contact lens type and spend their own money without their parent’s knowledge, though clearly they cannot enter into contracts (such as direct debit or home delivery schemes) on their parent’s behalf.

Whether a child is Gillick competent is a matter for the registrant responsible for the service/transaction involved and nobody else. Furthermore, it does not follow that if a child is competent to consent to one service, say collecting their glasses alone on the way home from school, they are also competent to consent to another intervention such as the fitting and supply of contact lenses.

A well-known CET scenario outlines a case where a child was deemed Gillick competent when supplied with contact lenses, but presents some months later (along with her mother) with signs and symptoms of sexually transmitted chlamydial adult inclusion conjunctivitis requiring urgent referral to an STD clinic as well as ophthalmology, and the need to contact any partners for them to be treated too. The answer to such scenarios is always ‘it depends’ but it can be seen that the capacity to consent to a situation where there is a low risk of harm cannot be automatically transferred to situations where the risk is real and harm certain if appropriate action is not taken.

Anterior Eye Assessment

It is beyond the scope of this article to go into detail about what should be included in a contact lens fitting or aftercare check-up, and the associated techniques, however practitioners are often witnessed at CET discussions to argue about whether or not assessments such as lid eversion, fluorescein instillation, and keratometry are always necessary on every patient every time they attend. It has been held that regular lid eversion, aside from being uncomfortable, can reduce lid tonus over the long term, and that fluorescein requires leaving lenses out, which is very inconvenient for patients, yet both are clearly necessary on occasion.

Case Study – Is Keratometry Really Necessary?

In a large contact lens practice two contact lens opticians, both with over 30 years of exclusive full-time fitting experience (ie they fitted lenses all day every day and did not also dispense for example) disagreed on whether keratometry was really necessary to the fitting of contact lenses. This caused difficulties when one followed on from the other and shared the fitting or aftercare of a particular patient. The author was called on to mediate.

ECP 1

‘Keratometry is necessary for determining the radius of curvature of the cornea and the initial selection of contact lens base curve. It is also a benchmark so that changes to corneal topography can be detected and monitored over the longer term.’

ECP 2

‘Keratometry is an unnecessary waste of time since it only measures the central few millimetres of the cornea and the most important part of the anterior eye in terms of contact lens fitting and ocular health is the para-limbal region. Most lenses come in only one base curve and at any rate any significant deviation from a normal corneal curvature can be determined ‘by eye’ using the slit lamp alone. Keratometry is only really necessary for complex gas permeable lens fitting such as back surface/bi-toric lenses or orthokeratology.’

As the two ECPs often shared responsibility for the contact lens fitting it was necessary to come to some form of accommodation so that each was happy to follow on from the other. A peer discussion meeting was held to review a few representative samples of records. A trainee contact lens optician and a pre-registration optometrist (both also registered dispensing opticians) were also invited to give an up to date perspective of what is taught currently.

The conclusion was that each opinion was valid, however, so that the ECPs could work together more happily, the practice invested in a new autorefractor with corneal topography/keratometry function so that Ks could be measured by support staff in advance of appointments.

Interestingly soon afterwards, following a stroke, ECP 2 was suspended from the register due to ill health. As a pre-cursor to returning to work his records were reviewed by the General Optical Council who, although making comment on legibility, and as is usual requiring significant CET to be completed, expressed no opinion on the absence of keratometry readings.

Contact Lens Instruction

Teaching patients how to apply, remove and care for their lenses, and what to do in the event of an adverse incident or emergency is a statutory obligation of the ECP that fits the contact lenses (figure 6). Practitioners may delegate the instruction of patients in the handling and care of lenses to suitably competent support staff. A so-called TWI (trial with instruction) or A&R (application and removal) must be supervised by the contact lens practitioner, an optometrist or a dispensing optician. No patient must be allowed to leave the premises unless and until they can competently remove their contact lenses.

Figure 6: Teaching patients how to apply, remove and care for their lenses is a statutory obligation of the ECP that fits the contact lenses

Figure 6: Teaching patients how to apply, remove and care for their lenses is a statutory obligation of the ECP that fits the contact lenses

According to the GOC supported website www.loveyourlenses.com contact lenses are enjoyed safely by millions of people, and while most wearers will never experience problems… there is a small risk of developing potentially serious problems. It recommends the following ‘do’s and don’ts’:

- Have regular review appointments as advised by your eye care practitioner

- Always wash and dry your hands prior to handling your lenses

- Always rub, rinse and store your lenses in the recommended solution before and after each use (except single-use lenses, which should be discarded/recycled where possible after each wear)

- Always clean the lens case with solution, wipe with a clean tissue then air-dry after each use by placing the case and lids face down on a tissue

- Always apply the same lens first to avoid mixing them up

- Check the lens is not inside out before applying

- Check the lens is not damaged before applying

- Handle carefully to avoid damaging the lens

- Apply your lenses before putting on make-up

- Remove lenses then remove make-up

- Keep your eyes closed when using hairspray or other aerosols

- Replace your lens case at least monthly

- Discard lenses and solutions that are past their expiry date

- Wear only the lenses specified by your contact lens practitioner

- Stick strictly to the recommended wearing schedule and replacement frequency

- Make sure you have an adequate supply of replacement lenses or a spare pair

- Have an up-to-date pair of spectacles for when you need to remove your lenses

- If you feel uncomfortable, or your vision is blurred, or you experience eye redness you should remove your lenses immediately and consult your eye care practitioner.

- Do not use tap water, or any other water, on your lenses or lens case

- Do not sleep in your lenses unless specifically advised to by your practitioner

- Do not use your lenses for swimming, hot tubs or water sports, unless wearing tight fitting goggles

- Do not share contact lenses or wear any lenses not specified by your eye care practitioner

- Do not wet your lenses with saliva

- Do not put a lens on the eye if it falls on the floor or other surface, without cleaning and storing again

- Do not re-use or top up solution – discard and replace with fresh solution each time lenses are stored

- Do not decant solution into smaller containers

- Do not wear lenses left in the case for more than seven days without cleaning and storing them in fresh solution

- Do not wear any lens overnight if you are unwell

- Do not wear your lenses when showering

- Do not switch the solution you use, except on the advice of your practitioner

- Do not use any eye drops without advice from your eye care practitioner

- Do not apply a lens if it is dirty, dusty, or damaged

- Do not continue to wear your lenses if your eyes do not feel good, look good or see well

Patients should be told: ‘If in doubt leave them out,’ and encouraged to ask themselves three questions, each time they wear lenses:

- Do my eyes feel good all day long with my lenses in? – no discomfort

- Do my eyes look good? – no redness

- Do I see well? – no unusual blurring with either eye

If the answer to any of these questions is no, they should leave off their lenses and consult their ECP immediately, who will advise you on what to do next. The ECP should also be available to answer any questions the patient may have, and it is good practice with new patients to make a courtesy call a few days to a week after they have taken away lenses for the first time to ask how they are getting on with their lenses, answer any questions they may have and, if necessary, invite the patient for another teaching session.

Contact lenses are a medical device and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has produced a guide to buying contact lenses for personal use. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/medical-devices-information-for-users-and-patients#contact-lenses.

All patients, including those that are new to contact lenses, experienced wearers that are new to the practice, and all other patients following updating of the guidance, should be issued with the above guidance or something similar in writing. This may take the form of a patient compliance agreement outlining their agreed wearing schedule, personal aftercare regimen and the risks of contact lens wear. The patient should sign two copies, one to be retained by the patient and a second signed copy should be kept with the record. A new agreement must be issued whenever there is a change in advice or wearing schedule or it is clear from the Px history and symptoms that they are non-compliant or cannot remember the advice they have been previously given.

Case Study – Who Can Teach?

On inspection of the Opticians Act, part 4, s25(5)(b), it is clear that the provision of instructions and information to contact lens patients is a function restricted in law as part of contact lens fitting. What is not clear is whether such a restricted function can be delegated, like paediatric ophthalmic dispensing, to anybody, or whether it can only be delegated to, for example, student optometrists, student contact lens opticians or student dispensing opticians. It is also not clear whether a dispensing optician can carry out a ‘teach’, or supervise assistants, in their own right.

Observation in the real world shows that in most large contact lens practices the instruction of patients is carried out by an optical assistant and in many cases the ECP that fitted the lenses may not be in attendance at the time, although another registrant must be on the premises and in a position to intervene. Clearly it is common for more than one ECP to be involved in carrying a fitting to completion, and the Act makes provision for it to be carried out by several practitioners, requiring under s25(6)(b) the last person involved to issue the specification. On the other hand, small practices have been known to schedule application and removal (A&R) appointments on non-clinic days when only the dispensing optician is available to supervise.

Until it is tested in court, or at fitness to practice proceedings, the legality of a dispensing optician conducting A&R appointments in their own right without a contact lens optician or optometrist on the premises remains in doubt, however, in this author’s opinion dispensing opticians who choose to practice in this way and supervise optical assistants who instruct patients can rely on the GOC mandated contact lens competency required of all dispensing opticians, which includes: ‘the ability to remove a lens in an emergency, if feasible, and the ability to discuss the use of care regimes.’ Requiring dispensing opticians to have these abilities would logically lead to a presumption that they would use these skills in their day to day role in practice thereby passing the Bolam Test and the Bolitho Test in defence of an accusation of clinical negligence.

The first dispensing optician to find themselves at a justified fitness to practice hearing relating to a contact lens instruction appointment is more likely to be found negligent rather than to have practiced illegally. However, where supervision of an assistant is involved, and a patient is harmed, then the principle of Res Ipsa Loquitur (‘the fact speaks for itself’) is likely to be invoked as proof that the supervising registrant (or alternatively the employer) is vicariously liable (ie answerable for the actions of another) and therefore at fault. The fact that there have been no cases, and therefore no legal precedent has been set suggests that patient safety is not jeopardised. The same logic can also be used to justify a dispensing optician who is not qualified in contact lens fitting supervising the supply of contact lenses to restricted categories of patient, or alternatively being responsible for the general direction of supply to non-restricted categories.

Practitioners must make up their own minds, however, an alternative view of the above is that when the fitting ECP conducts the teach it may have considerable advantages. From a confidence point the patient may be more relaxed and familiar with the ECP and every interaction with the patient is an opportunity for the ECP to educate, reinforce and demonstrate the correct wearing and caring behaviour, minimise complications and potentially reinforce patient loyalty and reduce dropouts. It can be argued that anyone taking responsibility for the teaching process should be in a position and competent to assess the anterior corneal surface checking for any epithelial defects or insults arising from the teach. A dispensing optician working without a contact lens practitioner would need to refer the patient off the premises if they had any concerns about corneal insult or injury. While the law lacks clarity, Standards of Practice for optometrists and dispensing opticians6 are clear: ‘Recognise, and work within, your limits of competence.’

Legal Terminology

There are a number of terms often used when discussing legality or otherwise of clinical intervention that it would be useful, at this point, to clarify.5,6

- Bolam Test: in cases of alleged clinical negligence a test used to determine the standard of care owed to a patient. Providing a responsible body of medical opinion holds the same view then there is no breach of duty of care. (Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957])

- Bolitho: subsequent to Bolam it has also been held that it is not sufficient for other clinicians to hold the same opinion the clinician accused of negligence must also have behaved ‘reasonably’ and ‘logically’. (Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority [1998])

- Montgomery: clinicians must provide information about all material risks; they must disclose any risk to which a reasonable person in the patient’s position would attach significance. (Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC)

- Res Ipsa Loquitor: [Latin: the thing speaks for itself] A principle often applied in the tort of negligence. If a patient comes to harm and the cause was under the control of a practice, then in the absence of evidence it can be presumed that the practice was at fault if it cannot be proved that an individual registrant was at fault. Similarly, a supervisor is at fault if they are aware that they are supervising, on the premises and able to intervene if the action of a supervisee causes harm since the level of supervision must not have been appropriate.

- Vicarious liability: where one party is answerable for the actions of another. In optics a supervisor is answerable for the actions of a person to whom they delegate. If an action is not supervised, (ie a supervisor is not on the premises or able to intervene, or not aware that they are supervising, or the task does not require supervision), then the employer is answerable. ABDO, in its August 2021 survey about professional indemnity insurance, says: ‘Vicarious liability is a legal principle which means that employers can be held liable for their employees’ negligent acts, omissions or errors where these arise in their course of their employment.’

Contact Lens Specification

Following the completion of a contact lens fitting a specification for the lenses must be issued to the patient. There is however some doubt as to what constitutes a fitting and therefore at what point the specification must be handed over and it is important to be clear with patients, especially those who clearly intend to order lenses from elsewhere afterwards. The Opticians Act s25(9)(a)(b) define fitting to mean ‘assessing whether a contact lens meets the needs of the individual; and where appropriate providing the individual with one or more contact lenses for use during a trial period’. It is generally accepted that a fitting is not complete until after the patient has returned for a check-up after a sustained period of wear following their initial assessment and fitting consultation(s). The patient must have built up their wearing time to the recommended maximum with no ill effects or compromise to ocular health before the fit will be deemed a success, and only then need a specification be issued.

A specification must include:

- Patient name and address

- Date of birth if under 16

- Signature, name and GOC number of ECP

- Practice name and address

- Fitting completion date

- Specification expiry date

- Contact lens replication details

- Other necessary clinical information

Most of the specification requirements are self-explanatory. However, the last three listed often cause confusion and patient complaint and merit further discussion.

Expiry date is a matter for the contact lens practitioner that completes the fitting and is decided upon based on the clinical needs of the patient. It is typically around six to 12 months. Given the requirement for a patient to have valid sight test prescription the contact lens specification should never be valid for more than two years. However, the expiry date can, and often is, much sooner in relation to the fitting completion date and normally coincides with the date on which the patient falls due for an aftercare check-up. For extended wear patients who are seen every three months, or for a patient whose sight test prescription was already close to the two-year limit at the time of fitting, then a three-month specification expiry date might be reasonable. However, for most patients six or 12 months appears to be the norm.

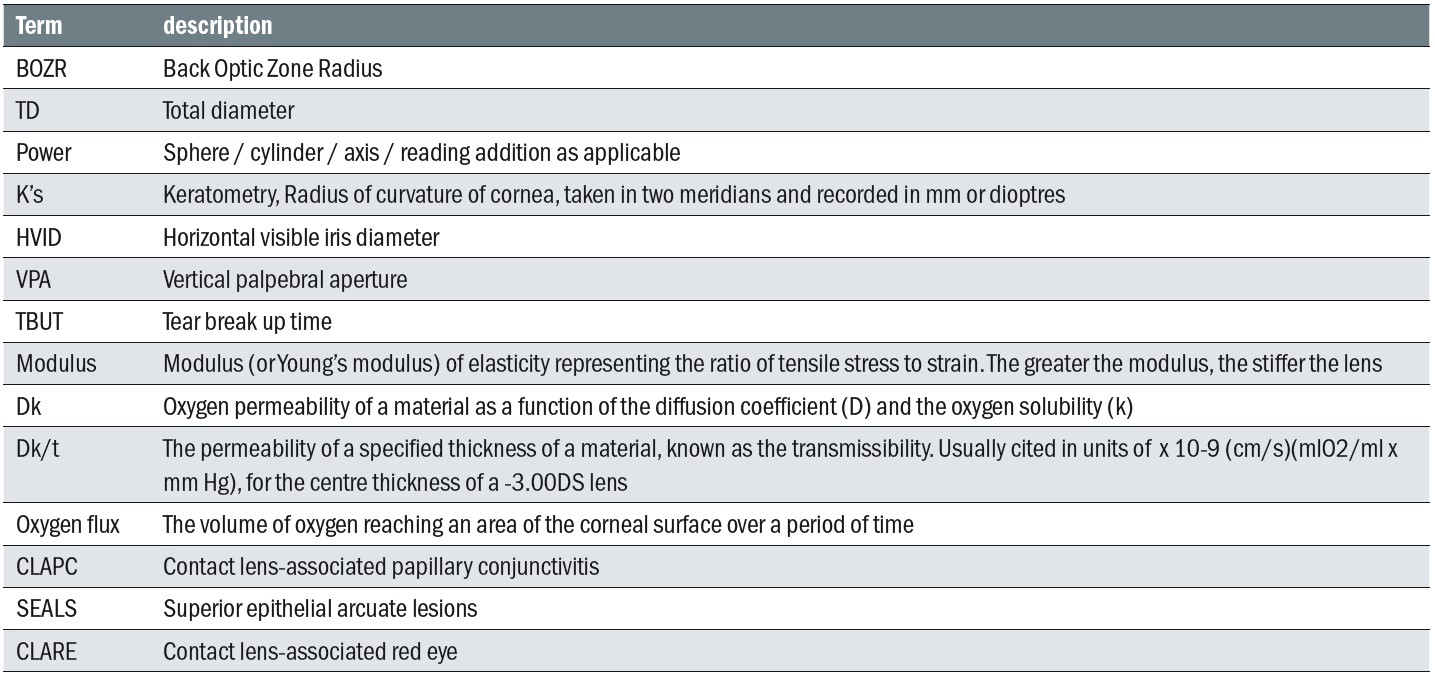

Contact lens replication details should include the lens brand and design, and if a private label product the material. Standard parameters (see table 1 for abbreviations) include BOZR, TD, Power (sphere, cylinder, axis, and addition as applicable), but may also include multifocal design option, handling tint, cosmetic tint/design, engraving and so on. The important thing is that any supplier seeking to supply the patient with lenses in relation to this specification can do so without the need to refer back to the original fitter.

Table 1: Common contact lens terms and abbreviations

Table 1: Common contact lens terms and abbreviations

A specification should also include ‘such information of a clinical nature as the person fitting the lens considers to be necessary in the particular case’. This might include, for example, details of a preservative free solution system where a patient has previously reacted badly to a preserved system or could include maximum wearing times if a patient has had issues relating to overwear in the past. Such additional information often accompanies a short expiry date interval.

Contact Lens Supply – Supervision and General Direction

The fitting of contact lenses (including zero powered contact lenses) is a fully regulated function that can only be carried out by a registered contact lens practitioner who must, once fitting is completed issue a contact lens specification – for those lenses. The responsibility for the current fitting specification remains the responsibility of the prescribing contact lens practitioner, being the contact lens optician, optometrist or medical doctor who fitted the lenses or who has most recently performed an aftercare consultation. Fitting is distinct from supply or sale of lenses.

The supply of all optical appliances (spectacles, low vision aids, and contact lenses) to regulated groups are subject to the same regulations. For clarity, the sale of contact lenses to under 16s, and adults registered as sight impaired, must be affected by or under the supervision of a registered contact lens practitioner.

For all other patients (non-restricted patients) the supply need only be under the general direction of a registered optician, who need not be on the premises, and who may be a dispensing optician. This includes warranty replacements and repeat supplies, but may not include free trials of lenses (for example, to help choose new spectacle frames) where the specification is different (or non-existent) unless sanctioned by a contact lens practitioner following a slit lamp examination and followed up afterwards.

The directing optician must be satisfied that the ordering, prescription verification and supply of contact lenses is carried out competently. This is normally achieved through staff training and the provision of standard operating procedures – written guidance to which staff can refer if unsure – and the availability of a registrant via phone or email if a particular circumstance has not been envisaged in the written procedures.

Under normal practice circumstances, the contact lens practitioner and the person who is responsible for the general direction of supply will be one and the same person. However, there will be occasions when other registrants direct supply. Only a qualified registered optician may exercise clinical judgment.

Where a patient subsequently purchases lenses from a third party, arrangements for aftercare pass to the third party. However, the practice that has fitted the patient may, indeed should, continue to send reminders at an appropriate interval.

Where a practice supplies lenses to an external contact lens specification, this should be under the general direction of a registered optician, who may be a dispensing optician, who should ensure clear records and that correct advice is given regarding wearing and aftercare. Private label products may be substituted for the generic brand, and vice versa, this being to the exact same specification in all respects barring name only.

The supply of contact lenses is a regulated function to all patients. However, there are special provisions that patients under 16 cannot purchase lenses remotely under the general direction rules applied to adults who are not registered visually impaired (figure 7). The practitioner must therefore ensure when issuing an Rx and specification for a child that all required information including the date of birth and expiry date are provided so that a new potential supplier can ensure compliance with the law and ensure that the sale is supervised by a registrant.

Figure 7: There are special provisions that patients under 16 years of age cannot purchase lenses remotely under the general direction

Figure 7: There are special provisions that patients under 16 years of age cannot purchase lenses remotely under the general direction

rules applied to adults

Optometrists, contact lens opticians and dispensing opticians must follow the Advice and Guidance of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians or the College of Optometrists as appropriate. However, this does not absolve them of responsibility to exercise clinical judgment when the patient’s best interests become paramount. Records must be kept of all clinical decisions and occasions where clinical judgment is exercised.

A contact lens specification should only be issued on final completion of the fitting process, which will be following an aftercare consultation sometime after the initial fitting so that the effects of wear can be properly ascertained and accounted for. This should be within three months of the first fitting providing the Px has attended all recommended aftercare appointments and no change is made to the specifications at the final checkup. It should be noted that it is not possible to complete a fitting without supplying lenses and therefore a contact lens specification cannot be issued unless an initial supply of lenses has been supplied and subsequently checked on eye. This initial supply is not counted as part of a sale but part of a fitting for the purposes of the relevant rules and legislation.

A contact lens specification should include all relevant details as per ABDO/CoO guidelines so a third party can accurately order identical lenses. In addition to all lens specifications the date of most recent eye examination and most recent contact lens aftercare check, as well as the specification expiry date should be included. The date of issue of the specification should be recorded on the Px record.

To avoid infringement of General Data Protection Regulations, duplicate specifications should be given in writing directly to the patient or by post. The appropriate stationery must be used in order that all relevant sections are completed and nothing omitted. Specifications must be signed by the contact lens practitioner or another practitioner who is qualified to fit contact lenses. Specifications may be sent electronically to another registered optician or a registered medical practitioner provided the patient has given permission for their data to be shared. A charge may be made for duplicate specifications.

When confirming prescriptions to third party suppliers (ie verifying the patient details that they recite to the fitting practice), by telephone, the permission of the patient must be given and all relevant details recorded including the date, identity and contact details of the third party. A contact lens specification must include the date of eye examination, the latest contact lens appointment and the expiry date. If a specification has expired, then it may not be confirmed, unless the third party is re-fitting the patient and requires a base line specification to work from. Practitioners are reminded that they are required to collaborate with colleagues in the best interests of patients, however, where a fitting has been highly complex and the practitioner can be sure that an original specification was issued then they may feel justified in charging for a duplicate to be supplied.

Additionally when contacted by a third party supplier a prescription for a child must not be confirmed without first confirming that the request is coming from a person/company that is entitled to supply and is registered in their own right to supply children and recording that information.

All non-registered staff must comply with the specific instructions of the contact lens practitioner regarding the supply of lenses. There can be no exceptions to a specific request that is non-routine and clearly marked on the Px record. For example, if it has been requested that the patient ‘must have an appointment to collect’ it is never permissible to simply hand out lenses whatever the circumstances. Students and non-registrants are reminded that only qualified registrants can exercise clinical judgment.

It is standard procedure not to supply lenses to a patient who is overdue a full eye examination and/or a contact lens aftercare appointment. For the avoidance of doubt the maximum validity of a contact lens specification is two years from the date of most recent eye examination. However, optometrists, contact lens opticians and dispensing opticians may exercise clinical judgment to supply a minimum quantity of lenses when it is in the best interests of the patient, in an emergency, or in the absence of a suitable appointment, for a short period of time.

It is the practitioner’s responsibility to ensure the patient is registered on the appropriate recall scheme. Where home delivery is the preferred option the procedures relating to overdue contact lens aftercare appointments and sight tests still apply. Practitioners should ensure overdue patients who are on home delivery schemes are identified and arrangements made for the lenses to be collected from the practice at the time of the appropriate appointment.

Home delivery of lenses to children and extended wear patients is to be avoided unless and until the patient has proven through repeated aftercare consultations that they are experienced, competent and compliant contact lens wearers in the eyes of their contact lens practitioner.

Conclusion

All registrants are reminded that although aspects of contact lens practice are core competences for all qualified registered opticians, they should only practice within their capability and be comfortable with any clinical decisions they make. In addition to the advice and guidance of the professional bodies registrants can find the relevant legislation and rules as detailed above, and referenced below, on the GOC website www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation. Contact lenses should form part of the process of gaining informed consent for all patients who are being recommended sight correction as one of the options available in addition to spectacles. Discussion of contact lenses should therefore take place as part of both the sight testing and dispensing process.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO is senior lecturer in ophthalmic dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians. Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CET provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College

Further Reading

The following legislation and rules used in the compilation of this article, and cited within the text, can be accessed via the GOC website www.optical.org/en/about_us/legislation and should be read alongside this article before attempting CET questions:

- 1989 Opticians Act Part 4 - Restrictions on testing of sight, fitting of contact lenses, sale and supply of optical appliances and use of titles and descriptions

- Contact lens specification rules 1989

- Contact lens qualifications rules 1988

- Rules on the fitting of contact lenses 1985

- Sale of optical appliances order of Council 1984

References

- General Optical Council. Standards of Practice for Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians. London : GOC, 2016.

- Risk factors with contact lens related suppurative keratitis. Stapleton, F, Dart, J K and Minassian, D. October 1, 1993, The CLAO Journal:Official Publication of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmologists, Inc, Vol. 19(4), pp. 204-210. PMID: 8261602.

- NHS. Children and young people. Consent to treatment. www.nhs.co.uk. [Online] [Cited: August 2021, 2021.] https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/consent-to-treatment/children/.

- NSPCC Learning. Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines. NSPCC. [Online] June 10, 2020. [Cited: August 31, 2021.] https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/child-protection-system/gillick-competence-fraser-guidelines.

- Oxford. Dictionary of Law. s.l.:Oxford University Press, 2015. 9780199664924.

- Tay, Catherine and Au Eong, Kah Guan. Medico-Legal and Ethical Issues in Eye Care. Singapore:McGraw Hill Medical (Asia), 2015. 9780071269940.