I am sure I am not alone in feeling increasingly guilty about the amount of single use packaging I am having to dispose of each week. That warm glow of self-satisfaction each Wednesday night, as I don my disposable vinyl gloves and sort out the recycling into the variously coloured plastic boxes ready for removal the next morning is being overtaken by misgivings about how consistently full each box is every week.

As a dry-eyed spectacle-phobic presbyope with a less than resilient ocular surface, I have relied on daily disposable contact lenses for clear vision ever since my accommodation went into decline. Yet, it is only recently that I have started to worry about the amount of plastic waste associated with my contact lens wear, especially when I look at this from a monthly rather than a daily output (figure 1).

Figure 1: One month’s contact lenses and packaging for one of the author’s eyes

Figure 1: One month’s contact lenses and packaging for one of the author’s eyes

There has been surprisingly little published research into the environmental impact of contact lens practice. Earlier this year, a paper was published in Contact Lenses and Anterior Eye describing an investigation carried out by a team from the University of Manchester and scientists from CooperVision that focused on disposal and recycling options for daily disposable and monthly replacement soft contact lens modalities.1 Since then, the study received exposure at the BCLA online conference and, more recently, the ABDO SEE Summit on the Environment.

This article aims to summarise the key findings of this paper against the backdrop of increasing awareness of the environmental crisis, awareness that is likely to affect the demands and expectations of our patients.

Background

Changes to the environment on Earth have been recorded for centuries. There are many such changes that can be considered separately, such as species extinction, loss of biodiversity, demographic imbalances, epidemic disease spikes, new diseases (such as Aids, Covid-19 and asbestosis), global warming, severe weather events, air quality degradation and many more. However, to view these as separate entities is to simplify a complex problem where all might be considered as interlinked and inter-dependent. This complexity, however, is one reason why public awareness and understanding has not kept pace with changes. And furthermore, it has taken a long time for the association between human activity and environmental degradation to be fully accepted, despite overwhelming evidence. This last point is very much linked with the fact that many contributory factors towards environmental damage also contribute greatly to economic growth and to perceived (in the short-term, at least) improvements in quality of life.

To better understand increasing unease about throwaway plastic products and packaging, such as mine regarding my contact lenses, it might first be useful to consider three important factors.

- Climate change; mean global temperature during the early 1800s, a time of great industrialisation in Europe, was measured at around 13.6˚C. In 1824, Fourier (whose theory underlies the way our OCTs image layered structures) showed through calculation that the Earth’s atmosphere acted as an insulator. In 1859, Tyndall (as in the phenomenon allowing anterior chamber cells and flare assessment) described how changes to the constituent gases in the atmosphere could directly influence climate. Subsequent decades saw a greater dependence on fossil fuels whose combustion produced gases, such as carbon dioxide, that enhanced the insulator properties of the atmosphere such that, by 1960, the mean global temperature was calculated as 13.9˚C. Steep rises in population, industrialisation and emissions have led to a rise in the rate of increase in global warming (an increase that is sometimes visualised as the controversial ‘hockey-stick graph’ much pounced upon by cynics as an over-simplification but now agreed to reflect change accurately) leading to a current mean global temperature of 14.8˚C, the warmest in tens of thousands of years. Levels of CO2 in the atmosphere run at 415ppm, the highest in millions of years.

- Disposability; the term ‘disposable’ first made its appearance in the 1640s, then meaning ‘ something that you can live without.’ Only in 1943, very much linked with the sudden introduction of plastics, disposable assumed the meaning of ‘single use,’ something that can be discarded after use, and replacing the adjective ‘throw-away’. Prior to plastics, mass production had already made disposable products, such as paper collars for shirts, popular and seen as convenient and cheap. As popular as this convenience was for the consumer, disposability also proved to be profitable for manufacturers. Indeed, many business models were developed to encourage disposability, such as the two-part pricing introduced by a certain King C Gilette who realised that he could easily recoup the loss in selling an under-priced razor by requiring customers to continually purchase disposable blades; a business model still used today by games console manufacturers.

- Plastics; increased use of carbon-based fuels drove interest in research into uses of the many and various by-products of oil and coal after refinement. This work led to the generation of a wide range of long chain carbon polymer-based materials found to be capable of great resilience and able to keep almost any shape, colour strength, flexibility, required texture and transparency as required. In other words, materials that were plastic. The cheapness of manufacture and great versatility of plastics meant that they were ideal for disposability. As synthetic materials, however, they had molecular bonds in their polymer structure not found in nature and so could not easily be degraded by natural processes. Increased production (itself a source of harmful emissions) and poor decomposition has led to an accumulation of plastics, much of it in particulate form capable of damaging all forms of life.

Public Awareness

This article is first being published in the run up to the COP26 summit to be held in Glasgow in November 2021. All the world’s media will focus on this event to report whether the main polluting countries of the world can agree on measures to address the increasingly worrying impact of their individual contributions to environmental collapse. It is worth remembering, however, that such media attention is a new thing when one considers the timeline already mentioned. And while a recent survey of news editors has suggested that 80% of respondents are likely within the next 12 months to expand their level of climate-focused journalism,2 reasons for a lack of reporting or acceptance of facts about a climate crisis are still present.

Wolfgang Blau, a founder of the newly set-up Oxford Climate Journalism Network (OCJN), part of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, has highlighted a number of obstacles to coverage of environmental matters by news editors:2

- Recency; perception of the crisis as a future concern will always tend towards procrastination.

- Geographic vicinity; the greatest impact of climate change at present is upon developing countries, mainly in Africa and, ironically, those having contributed least to the problem in terms of emissions. News that directly affects consumers will always tend to be prioritised over that having impact elsewhere.

- Process versus event; environmental decline is a cumulative problem and often perceived as something that will have the greatest impact in the future, so has less immediacy than an actual, specific event. This is why we see reports of specific events, such as large forest fires or floods, while an in-depth analysis of climatic change is far less likely to generate a single headline report.

- Complexity; soundbites are difficult to construct from a complex concept with multiple influences and variables (see, for example, any recent media explanation of the difference between weather and climate). Few news editors would risk their market by headlining with a complex, heavily referenced feature offering overlapping inferences. On the other hand, a reductivist approach with a snappy headline will always be vulnerable to criticism and accusations of bias.

- Public interest; is the story in the public interest and so demands reporting, despite the previously listed concerns?

According to Blau, it is the last on this list where there has been a tangible shift in attitude resulting in an increase in public awareness of the problem,3 an awareness that is finally being viewed less and less as a debate between deniers and proponents. Commercial and corporate interests have, however, muddied the waters somewhat. Just as initial studies showing the dangers of smoking were successfully shielded from a public that enjoyed smoking by a tobacco industry with deep pockets and links within media and governments, such is still the case regarding global warming. For example, at the time of writing, reports are coming through of countries lobbying to have recommendations (such as phasing out fossil fuels or decreasing meat consumption) removed from COP26 outcomes.

That said, the concept of environmental decline is now established in the public mind in the UK, helped by the outpourings of respected authorities such as Sir David Attenborough and ‘new kid on the block’ Greta Thunberg.

In summary, patients will increasingly want to know about the environmental impact of what is prescribed by eye care professionals.

Contact Lenses

Contact lenses and their packaging are synthetic by design and present challenges regarding their biodegradability. In 2018, it was reported that 21% of contact lens (CL) wearers in the United States were flushing their lenses down the sink or lavatory, amounting to about 20 to 23 tonnes of waste water-borne plastics every year.4 Though this received widespread media coverage, it is surprising to note that, until the recent study by Smith et al,1 there has only been one previous paper published in the literature on the subject of CL waste.5 This 2003 study, also from a team based in Manchester, illustrated the environmental impact of waste generated through CL use, but there was no investigation into end-of-life disposal. Smith et al goes some way to address this, as will now be described.

Study design

The aim of the study by Smith et al was to examine the annualised waste and end-of-life disposal options with two representative soft CL modalities. These were:

- Somofilcon A soft CLs (clariti elite from CooperVision) used with multipurpose solution (All in one Light, CooperVision)

- Somofilcon A CLs (clariti 1 day, CooperVision)

Using a model that assumed compliant wear and care of CLs, the mass of material solid waste generated by CL use over a year was calculated for each modality. Disposal options were explored using recycling schemes available in Greater Manchester, which included household or specialist recycling streams as provided in increasing numbers of eye care practices, and the findings were used as a basis for making some recommendations for responsible disposal of CL waste.

Results

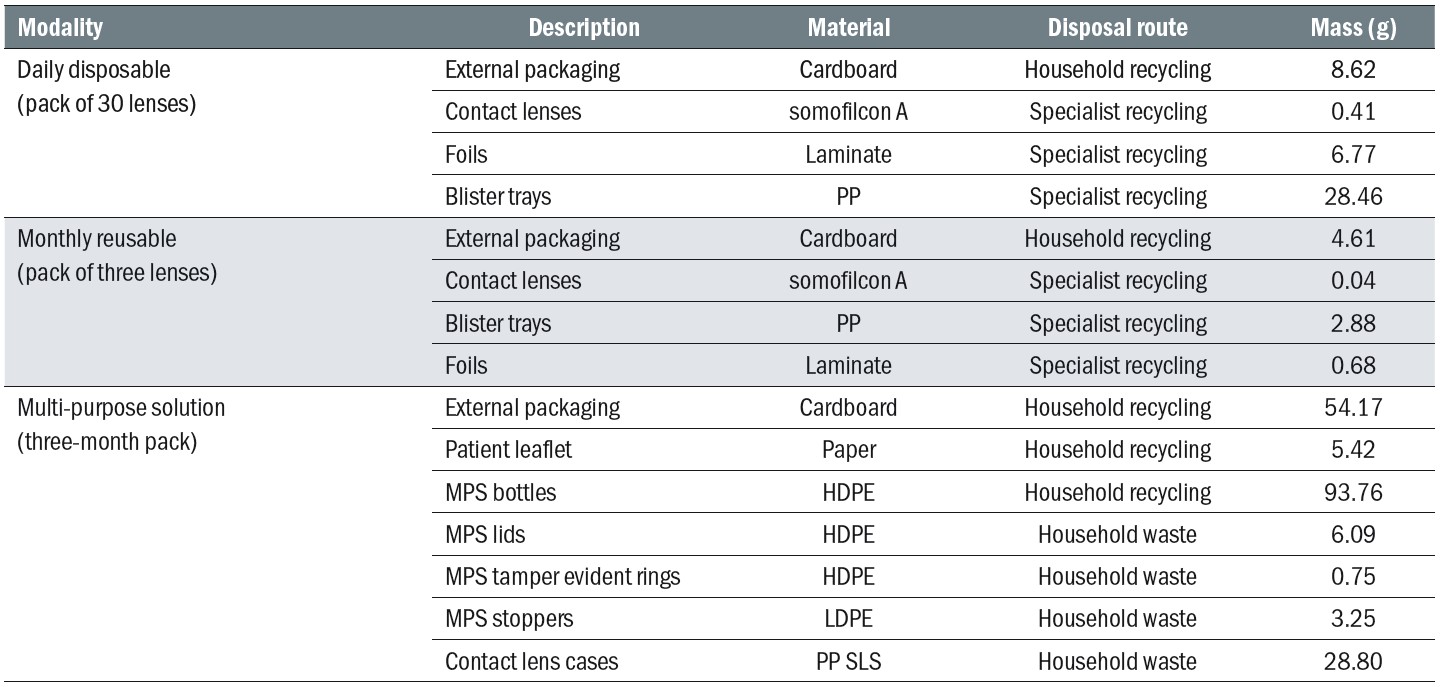

The mass of solid waste for each modality (including packaging, individual plastics and foils) was calculated along with the suggested route for disposal and is summarised in table 1.

Table 1: Description of the items within the audit included for analysis, the material composition, suggested disposal route and mass1

Table 1: Description of the items within the audit included for analysis, the material composition, suggested disposal route and mass1

(HDPE = high-density polyethylene; LDPE = low-density polyethylene)

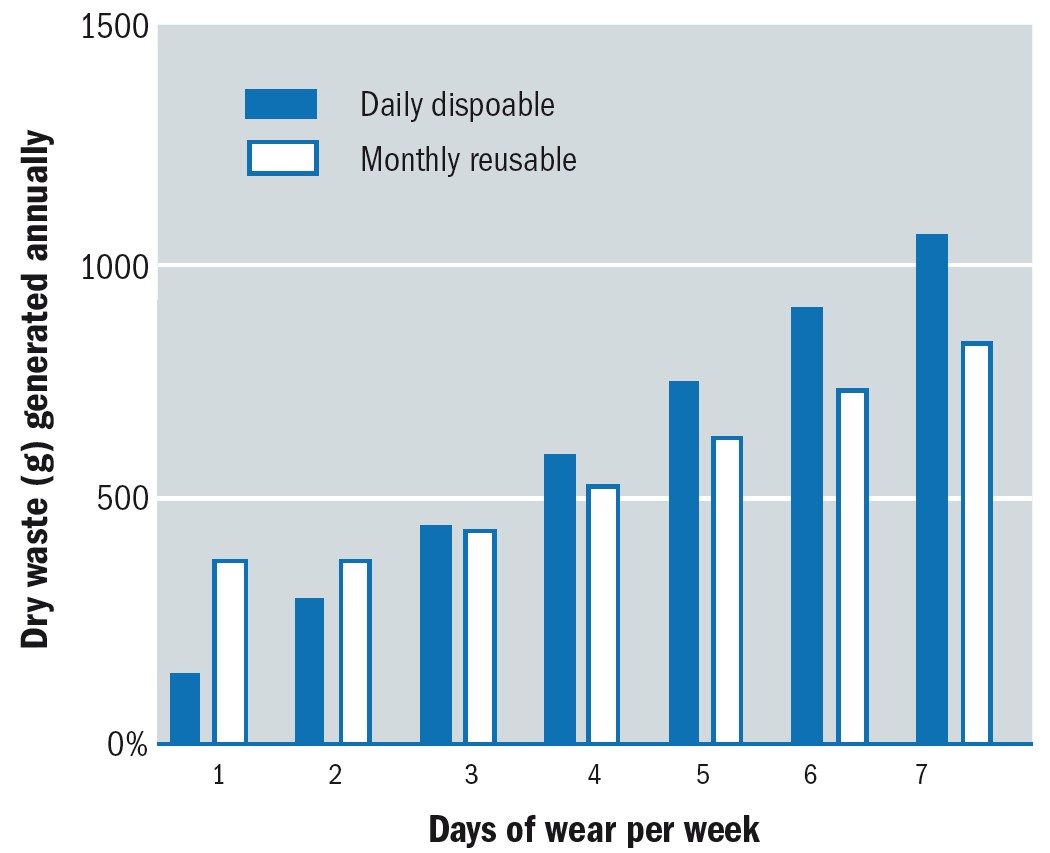

When considered over the course of the year, it was calculated that full-time daily disposable (DD) CL wear generates 27% more dry waste annually than reusable CL wear (1.06kg and 0.83kg respectively). However, during the course of the year, the relative waste generated by each modality varied (see figure 2). DD CL wear generates less waste than reusable lenses when CLs are worn one or two days per week. Waste generated is similar if lenses are worn three days per week (455g for DD lenses and 443g for reusable lenses). Wearing CLs four to seven days per week, DD CLs generate more waste than monthly reusable lens wear.

Figure 2: Annualised waste based on days of wear per week1

Figure 2: Annualised waste based on days of wear per week1

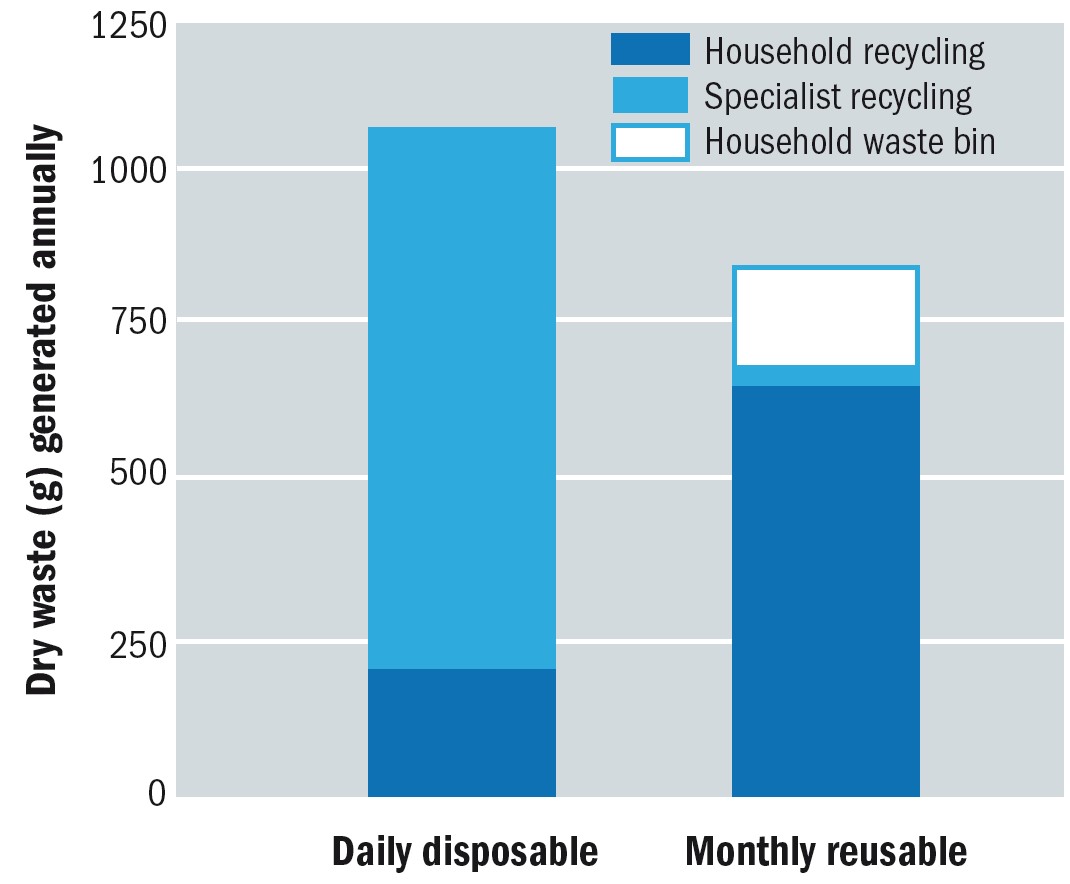

When Smith et al considered recycling options, using household recycling in conjunction with a specialist scheme for CL recycling, they found that 100% of DD waste can be recycled compared to 81% of waste from a reusable lens system (figure 3).

Figure 3: Recyclability of daily and monthly replacement options

Figure 3: Recyclability of daily and monthly replacement options

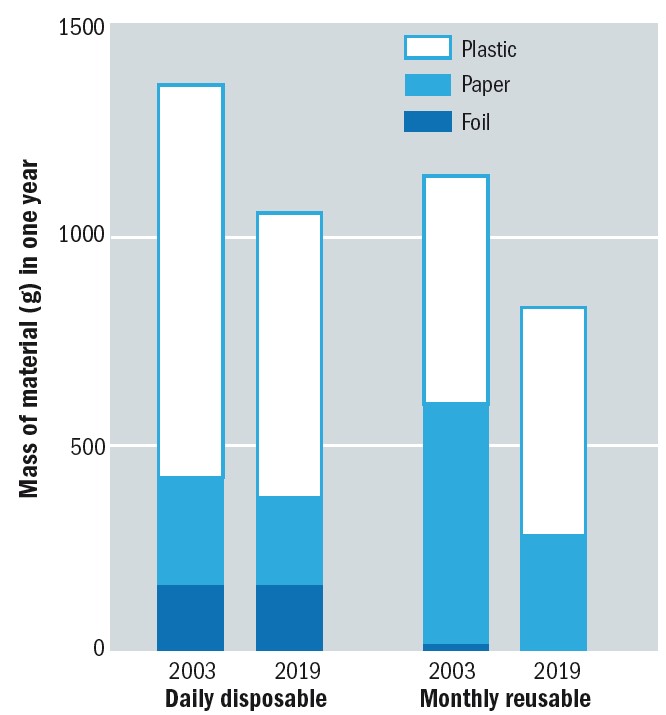

By comparison with the results from the older 2003 study,5 Smith et al confirmed that there had been a welcome reduction in the packaging associated with both wear modalities (figure 4).

Figure 4: Annualised waste generated by two representative replacement modalities comparing products from studies in 20035 and 20201

Figure 4: Annualised waste generated by two representative replacement modalities comparing products from studies in 20035 and 20201

Conclusions

Smith et al conclude that the ‘total waste generated by an individual CL wearer is relatively low, and the proportion of lens waste generated by full-time wear accounts for only a tiny fraction of annual household waste. Annual waste generated by full-time DD lens wear is not, in an environmental context, significantly different to reusable lens wear. DD lens wearers in the UK have access to recycling options that allow them to recycle 100% of waste.’

This author believes this data is important as it represents one of the first attempts at quantifying the environmental impact of what we, as ECPs, regularly prescribe to our patients. As patients become increasingly aware of the challenges facing the environment (figure 5), we should all expect to be asked about potential environmental impact and it is important that we always give information based on evidence rather than conjecture or opinion. I hope to see many more studies into other areas of eye health products and materials. ECPs are in a position to address our patients justifiable concerns and use that role to ensure that manufacturers and suppliers always strive to minimise any harmful impact presented by manufacture, distribution and disposal of products supplied to us.

Figure 5: Dried-up river in Marsalforn, Gozo as seen at the start of October, 2021. In October 2016, this was a raging torrent flowing into the sea

Figure 5: Dried-up river in Marsalforn, Gozo as seen at the start of October, 2021. In October 2016, this was a raging torrent flowing into the sea

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Sarah Smith, Eurolens Research, Division of Pharmacy and Optometry, the University of Manchester, for her support and advice in developing this article.

References

- Smith SL et al. An investigation into disposal and recycling options for daily disposable and monthly replacement soft contact lens modalities. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 2021 Mar 12:101435

- https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/risj-review/our-podcast-how-journalists-can-better-cover-climate-crisis Accessed 20/10/21

- BBC radio 4, The Media Show, 20/10/21. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/brand/b00dv9hq

- Rolsky C et al. Nationwide Mass Inventory and Degradation Assessment of Plastic Contact Lenses in US Wastewater. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020, 54 (19), 12102-12108

- Morgan SL et al. Environmental impact of three replacement modalities of soft contact lens wear. Contact Lens & Anterior Eye, 2003;26:43–6.