In the Western World the prevalence of refractive error is estimated at around 60% across the general population, rising from around 20% of children to close to 100% of elderly adults. The principal reason that so many more people need to wear spectacles or contact lenses as they get older is presbyopia – a term derived from the Greek meaning ‘old sight’. In this first article on the topic, we will describe the nature of presbyopia and present some of the challenges associated with dispensing presbyopic patients.

Background

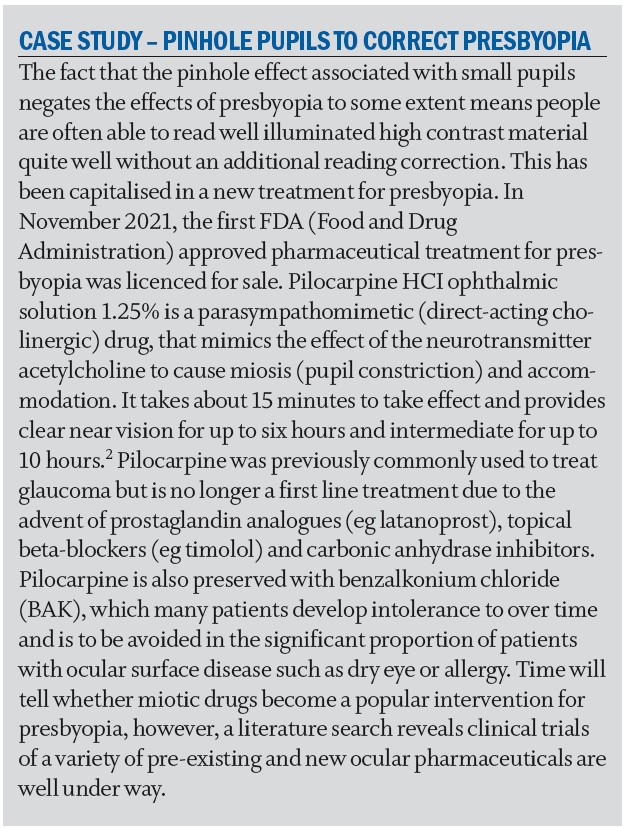

Presbyopia occurs as a result of the stiffening of the crystalline lens within the eye as it loses flexibility as part of the natural aging process. Although the ciliary muscle retains the same force of contraction the increased resistance encountered when the muscle acts on the inelastic lens causes a reduction in the eye’s ability to focus at near. The ability of the eye to focus at different distances is known as accommodation, and the distance the eye can see when fully accommodated is the near point of accommodation, which gradually recedes with age (figure 1).

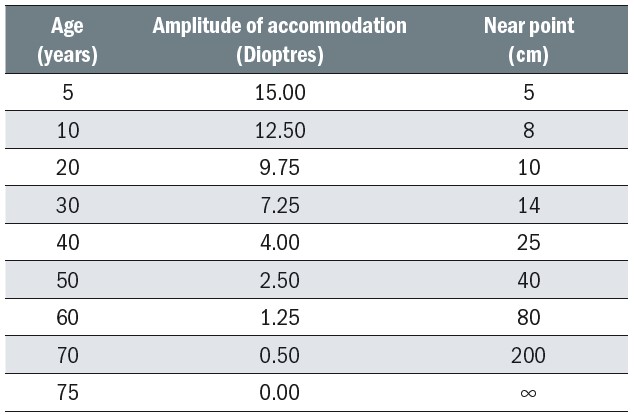

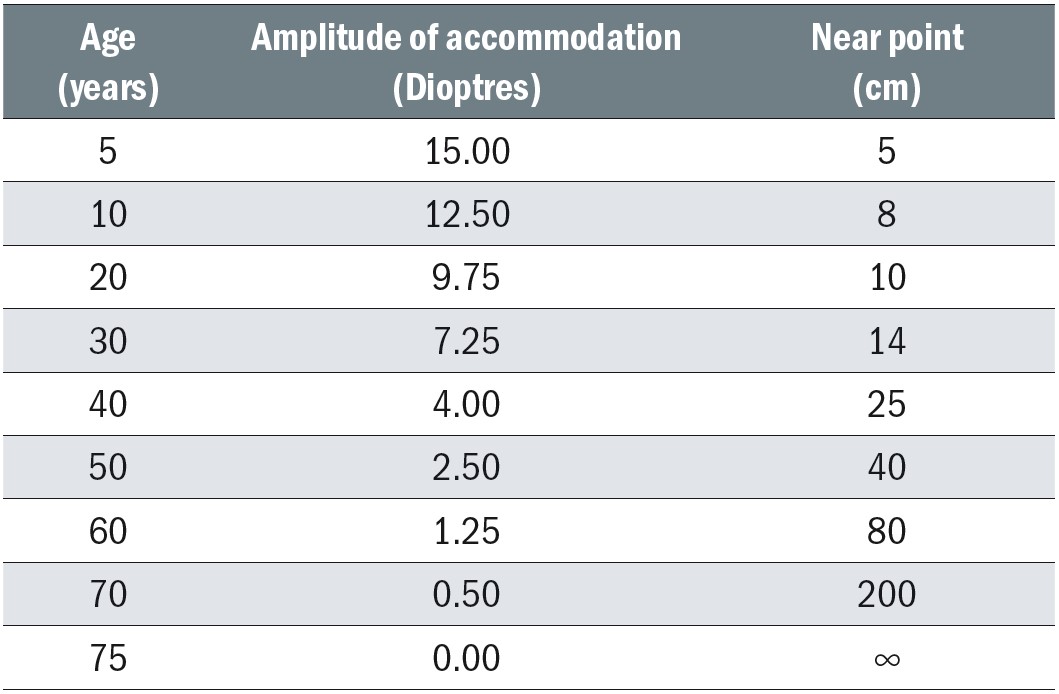

Figure 1: Declining amplitude of accommodation data according to Donders as cited by Schwartz1

Figure 1: Declining amplitude of accommodation data according to Donders as cited by Schwartz1

If the eye is emmetropic, or fully corrected for distance, then the near point is the reciprocal of the amount of accommodation. The average maximum amount of accommodation for various ages, and the associated near points are shown in table 1.

Table 1: Age, accommodation and near point for emmetropes

Table 1 clearly shows the reduction in amplitude of accommodation occurs from infancy and is not simply a phenomenon of middle age. The near points in table 1 are simply calculated as the reciprocal of the amplitude of accommodation and ignore the effects of depth of field, in particular that provided by the pinhole effect associated with tiny pupils that often accompany old age as, presumably, an evolutionary adaptation to presbyopia.

Presbyopia affects emmetropes, astigmats, myopes and hyperopes when the amplitude of accommodation has declined to the point where clear and comfortable near vision becomes difficult or impossible. Since accommodation increases the spherical power of the eye its reduction can be counteracted with a reading addition – positive spherical power in addition to any distance prescription that is required.

At some point during every day there is a need to be able to attain clear and comfortable vision at a variety of ‘working distances’ from very close to infinity. Working distances as close as 25cm are frequently observed with modern electronic devices such as mobile phones or tablet computers, and 35 to 45cm is commonly recognised as the typical range of working distances for routine close work such as reading a book, using a laptop, checking a watch etc. Slightly longer working distances are required for routine daily activities such as cleaning, cooking and viewing dashboard controls such as satellite navigation when driving. It is the responsibility of the eye care practitioner to firstly ascertain a patient’s requirements then advise on the most appropriate lens option. To do this accurately the range of clear vision that the patient can achieve must be determined and then compared to the range of clear vision the patient would like to achieve when wearing their spectacles or contact lenses.

Accommodation

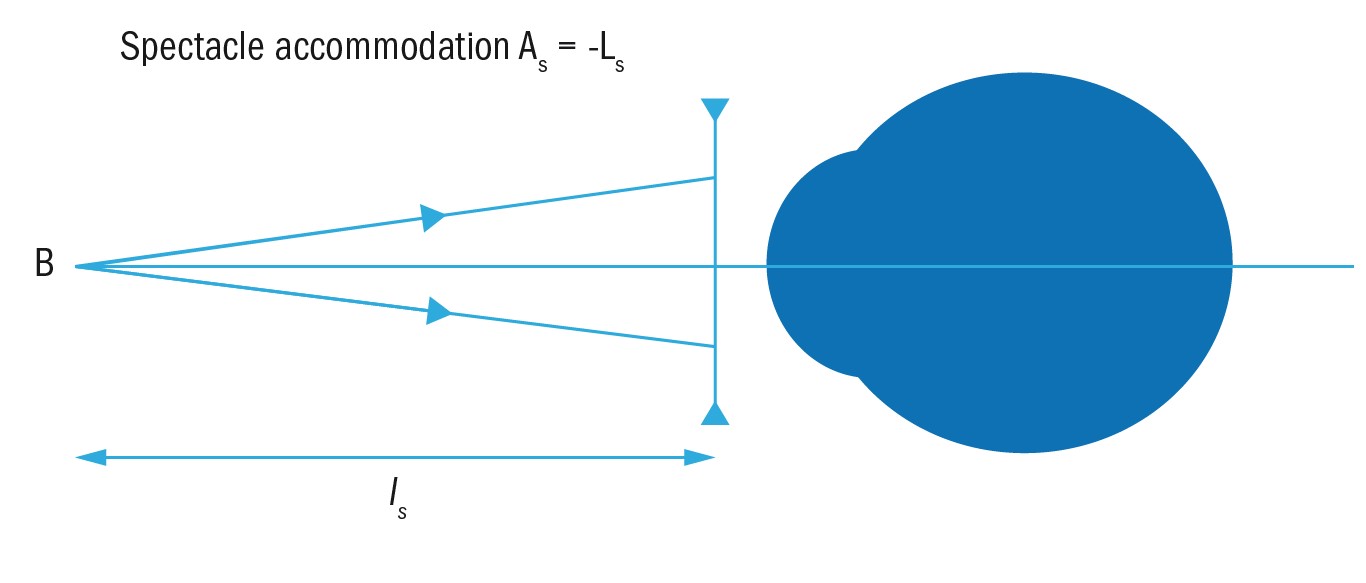

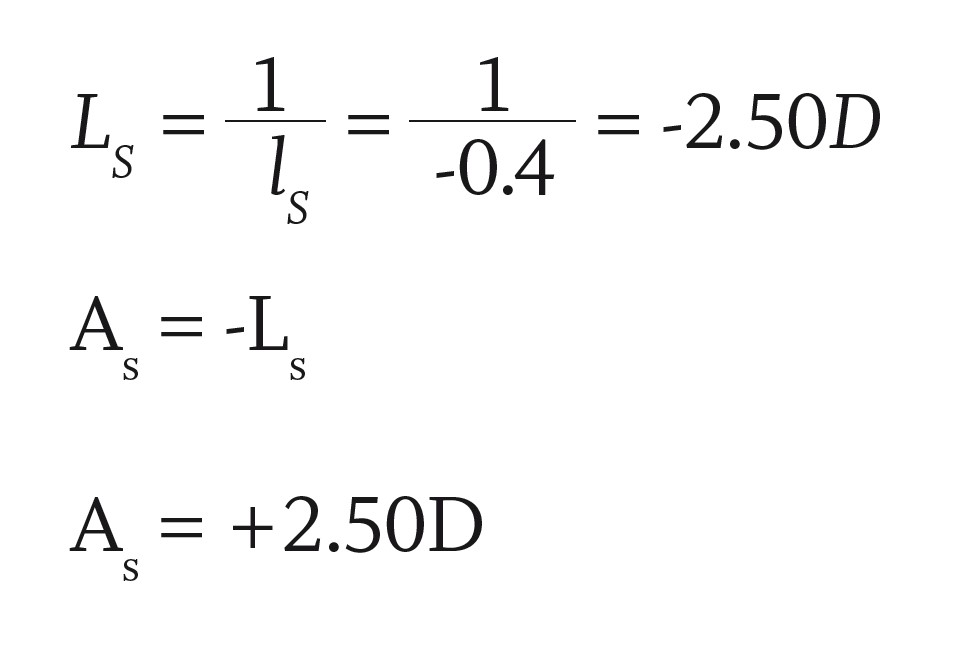

Spectacle accommodation; the amount of accommodation required to neutralise the vergence from a near object measured in the spectacle plane assuming any ametropia has been corrected (figure 2).

Figure 2: Spectacle accommodation

If an object is viewed at -40cm (-0.4m)

Ocular accommodation; the accommodation required measured at the reduced surface. Stepping the spectacle accommodation through the vertex distance to the ocular surface means myopes need exert less ocular accommodation than hyperopes in order to achieve the same spectacle accommodation and in part explains why the onset of presbyopia tends to be later in myopes and sooner in hyperopes compared to emmetropes.

In practice, the amplitude of accommodation (AoA) is measured in the spectacle plane wearing the distance correction so any ametropia has been corrected. Currently in the UK the RAF rule is routinely used for this measurement, although a near vision chart and tape measure will suffice – the AoA being the reciprocal of the closest distance (in metres) at which the near target can be seen clearly with the distance correction (if any) being worn.

These results aid the optometrist to establish the appropriate reading addition. The AoA will be recorded on the patient’s record and is a very useful piece of information for the dispensing optician to consider when deciding the best lens option for correcting the presbyopic patient. Dispensing a patient who attends the practice for dispensing only having been tested elsewhere and is either presbyopic or approaching presbyopia it can be helpful to determine the spectacle accommodation and near points thus avoiding potential non-tolerance issues. Freeman and Evans found that out of 36 prescription related non-tolerances 10 (27.78%) were due to near or intermediate addition error.3

Push up to blur

One method of measuring spectacle accommodation is the push up method (push up to blur) using the RAF rule (figure 3). It is important that the up to date distance prescription worn. Monocular amplitudes are measured first, which should be approximately equal, then binocular amplitude is measured, which will be greater as convergence drives accommodation.

Figure 3: The RAF rule used to measure push up to blur

Figure 3: The RAF rule used to measure push up to blur

The RAF rule is placed just below the patient’s nose although Burns et al4 suggest holding the rule in the primary position of gaze to avoid measurement error as well as moving the slider slowly towards the patient at approximately one dioptre per second and offering positive feedback to the patient.

At the point when the print just blurs the measurement can be read from the rule. It is worth remembering that this measurement can be prone to inaccuracy due to a failure to stop moving the target at the point where it ‘just’ goes blurred combined with patient tolerance of blur, relative image size and the pinhole effect mentioned above can lead to an over-estimation of 1.50 to 2.00DS.

Alternative methods include the minus lens method where minus power is added to any distance Rx when viewing text at a known near distance of say 40cm until the text becomes blurred, and the push out method where the target starts at the near end of the RAF rule and is pushed out until it becomes clear – this tends to yield an amplitude of accommodation slightly lower than the push up and blur method and many practitioners prefer to use the average of the two.

Systematic errors mean that no method of measurement of amplitude of accommodation is truly accurate, nevertheless it remains in practice an important clinical measurement useful in the determination of the patient’s addition(s) and in the advice to be given to the patient during dispensing.

True and Artificial Far and Near Points

The terms true far and near points refer to the ocular refraction at the eye.

True far point MR; the point conjugate with the centre of the macula at the unaccommodated eye.

True near point MP; the point conjugate with the centre of the macula by refraction at the fully accommodated eye.

Placing an optical correction in front of the eye gives an ‘artificial’ far and near point.

Artificial far point MR, art; the point conjugate with the centre of the macula by refraction at the corrected unaccommodated eye.

Artificial near point MP, art; the point conjugate with the centre of the macula by refraction at the corrected fully accommodated eye.

From this it can easily be seen that the range of clear vision with spectacles extends from the artificial far point to the artificial near point.

Understanding of the artificial far and near points of a spectacle correction are essential to ensure the most appropriate lens designs, and indeed additions, are selected when dispensing. Although a dispensing optician cannot prescribe a distance prescription, they are able to determine an addition for any purpose from far range intermediate through to extremely high adds for very close working distances as may be required by low vision patients, without the supervision of an optometrist.

Comfortable Near Point

In practice patients are not able to exert their full accommodative effort for very long without experiencing symptoms of asthenopia. The entire amplitude of accommodation may be used when performing short term exacting near vision tasks such as threading a needle or replacing a nose pad screw, however, if such exacting tasks, for example fine sewing work, are carried out for long periods then patients who are using their full accommodative reserves will experience eye strain and headaches.

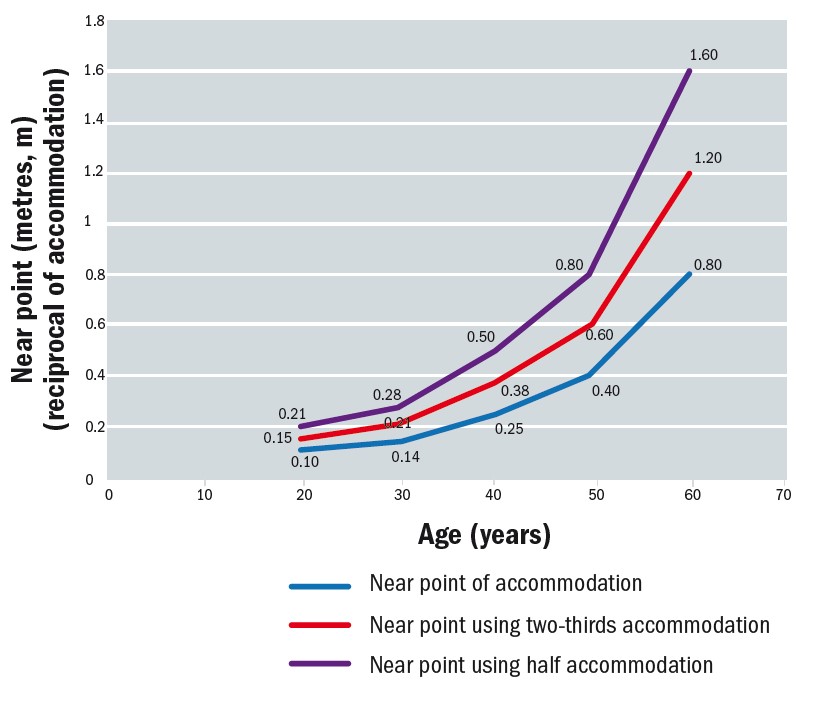

Consequently, it is necessary for the prescriber, and if appropriate the dispenser, to determine an appropriate addition such that comfortable levels of accommodation are used. Historically it has been felt that patients can tolerate continuous utilisation of two thirds of their amplitude of accommodation and this remains the advice in most ophthalmic dispensing texts, however, optometry texts seem to err on the side of caution, perhaps because of the systematic over-estimation of amplitude of accommodation, and state that only 50% of accommodation can be used comfortably for sustained periods.

This has significant implications for both prescribing and dispensing as figure 4 makes clear. If we take a 40-year old patient, who has on average 4.00D of accommodation (fig 2) giving a near point of 1/4m, or 25cm. We can see that if the patient sustains 50% accommodation then their comfortable working distance is now 0.50m, which for most people is beyond what may be habitual for prolonged close work. By the age of 45 the graph shows that patients whose lifestyle and occupational requirements demand concentrated near vision tasks at distance less than 50cm will certainly require correction for presbyopia. Many optometrists, especially those that are newly qualified, quote the age of 45 as the onset of presbyopia, which seems to have advanced five years since the authors qualified over 30 years ago. While myopes are indeed often able to cope in their distance spectacles until their mid-40s, thanks to effectivity, and the ability to remove their specs for demanding close work, the same may not be true of other patients.

Figure 4: Near points in emmetropes and patients wearing an up-to-date distance correction

Hyperopes, astigmats and myopic contact lens wearers are all likely to complain of symptoms relating to presbyopia from their mid to late 30s onwards and they should not be dismissed as being too young for reading glasses when the evidence, and specific patient concerns, strongly suggest otherwise. Most patients want help with reading when it becomes difficult or uncomfortable – they do not want to wait until it becomes impossible.

The reading addition

A good rule of thumb to estimate the add up until the age of 60 is +0.50DS for every five years over the age of 35, which provides tentative reading additions as in table 2.

Table 2: Estimated reading addition

Beyond the age of 60 the add relates more to the desired working distance, the artificial far point (or maximum working distance) for near, and any magnification that may be required due to any reduction in best corrected near visual acuity.

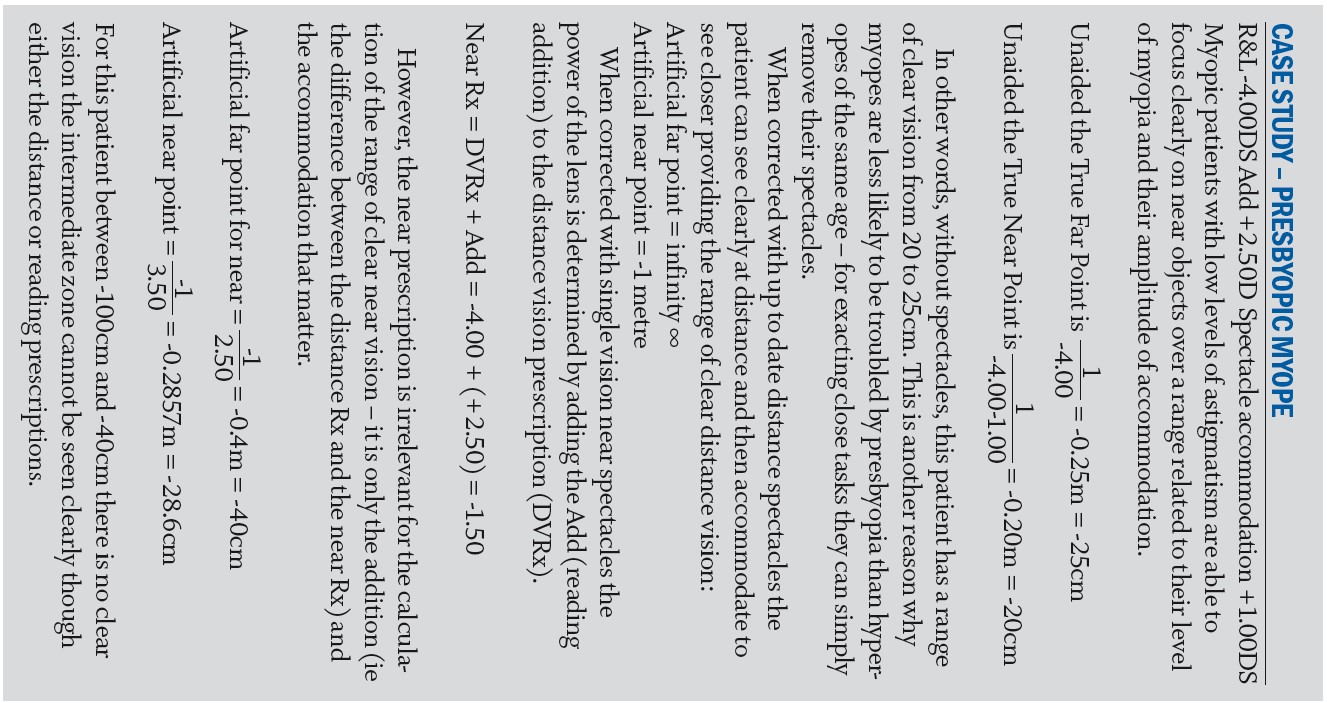

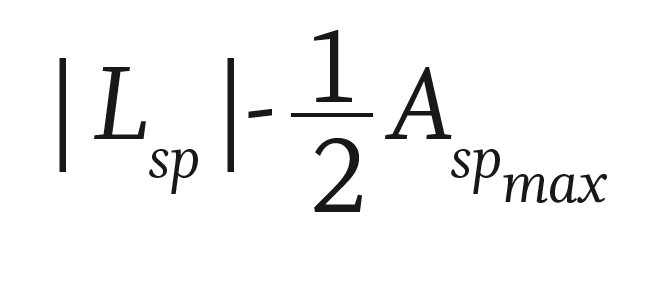

The addition is a function of the working distance, or the vergence from the near object being viewed, and the amount of accommodation that the patient can comfortably use. The usual relationship is:

is the modulus of the vergence from the near object at the spectacle plane and Aspmax is the amplitude of accommodation

An addition is always positive in power and must be added to the spherical part of any distance correction. If it is calculated as negative using the formula, then it is not prescribed.

Adds of +0.25D and +0.50D are also unlikely to be prescribed, although their use has increased dramatically in recent years with the dispensing of low add boost lenses aimed at people experiencing eye strain when using mobile digital devices. The formula above could just as easily have been written

which would yield an earlier onset of presbyopia and a higher add at a given age.

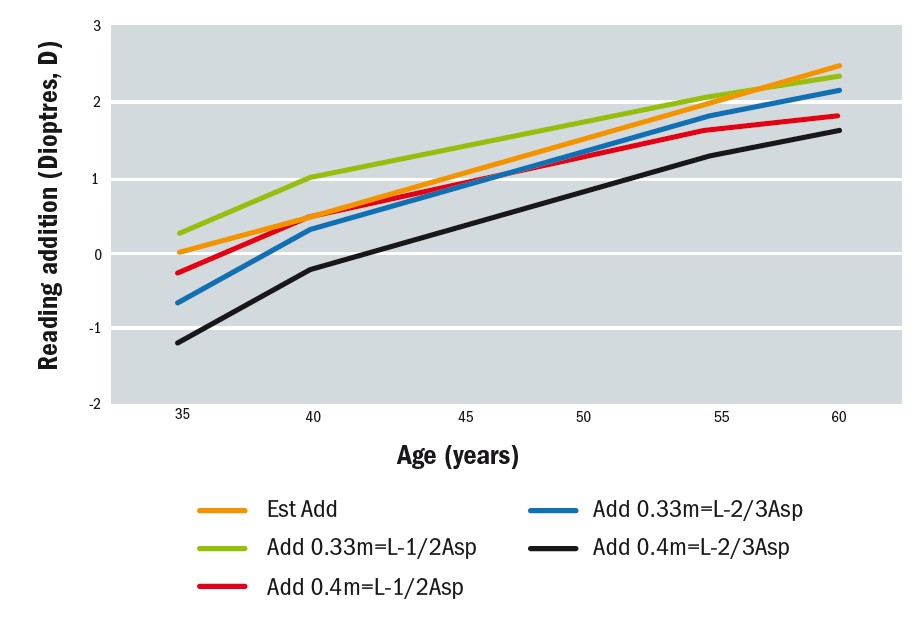

Figure 5 uses the average data for the amplitude of accommodation and then compares the add estimated using the rule of thumb to the calculated addition using 2/3 and ½ the amplitude of accommodation for two working distances: 33.3cm and 40cm requiring object vergences of 3.00DS and 2.50DS respectively. It can be seen that the rule of thumb estimation is a good fit to the average of the other methods although a +2.25DS add may be more appropriate for the average 60-year old rather than a +2.50DS.

Figure 5: Comparison of empirical methods of determining reading addition

Although the reading addition may vary slightly according to the patient’s amplitude of accommodation, working distance and so on, it is useful to keep in mind the expected approximate values for each. Firstly, for comparing to actual measured values and secondly in the event this information is not available at the time of dispensing for determining likely problems. The most common problem as presbyopes age and require stronger reading additions is the loss of intermediate vision with both the reading and distance prescriptions.

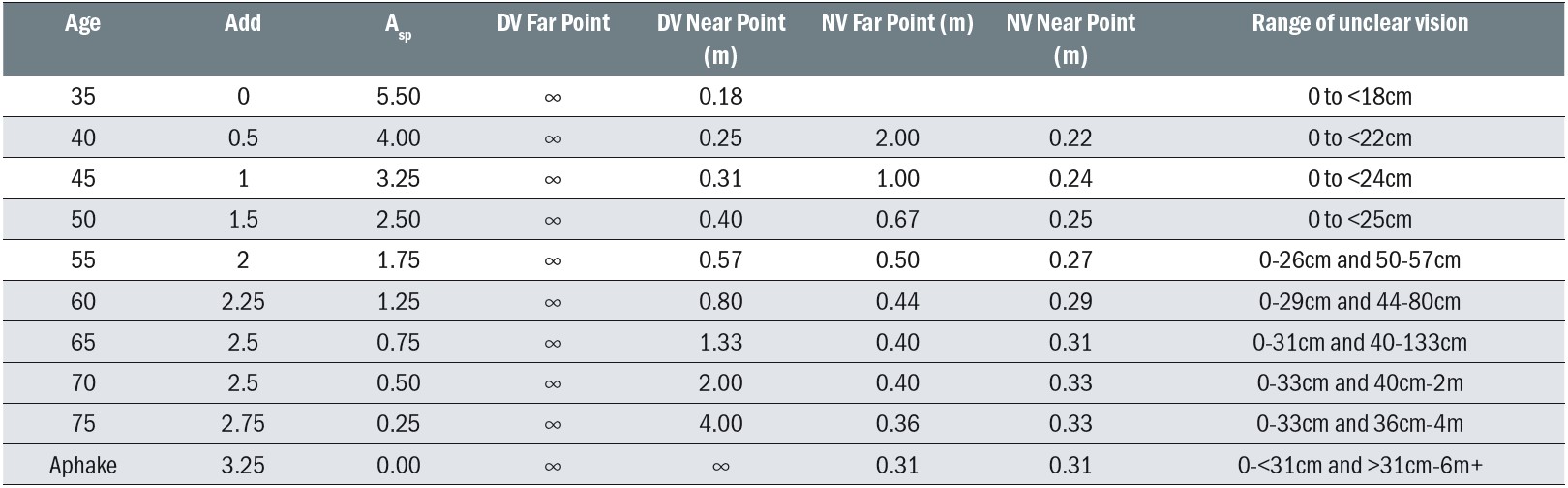

Table 3 shows the estimated addition and amplitude of accommodation, Asp, for a variety of patients aged 35 to 75, plus an aphakic patient with no accommodation. The data assumes that the patient is either emmetropic or has their distance ametropia fully corrected and therefore the far point for distance vision in all cases is at infinity. The near point with the distance correction in place, DV Near point, is simply the reciprocal of Asp, which reduces from 18cm aged 35 to 4m aged 75 ignoring the effects of small pupils and blur tolerance.

Table 3: The range of blurred vision for typical presbyopic patients reading addition

Table 3: The range of blurred vision for typical presbyopic patients reading addition

It can be seen that in the early stages of presbyopia the distance prescription will still be serviceable for most near vision tasks, and the near vision prescription will give a good range for intermediate. Aged 50 the working range in the distance and near prescriptions will still overlap. By 55 however, in addition to an inability to focus closer than 26cm, patients also find that whether they use their distance or reading Rx, items at a distance of 50 to 57cm cannot be brought into focus, and a third prescription for intermediate use is now necessary.

Correcting Presbyopia; presbyopia with emmetropia

Ready-to-wear spectacles

At its simplest level, presbyopia, when it affects subjects who are emmetropic and require no prescription to see clearly at distance, can be easily corrected with ready-made reading spectacles (figure 6), which should conform to BS EN 14139:2010 Specifications for ready-to-wear spectacles. Ready readers are available in positive powers, the same right and left, from +1.00 to +3.50DS even though the Opticians Act Part IV (27)2 includes powers up to 4.00D. This caters for all the typical reading additions previously mentioned. They should be clearly marked as medical devices (CE or post-Brexit equivalent), and also have the lens power and centration distance identified.

Figure 6: Ready readers

Figure 6: Ready readers

Patients with centration requirements significantly different from the average will suffer induced prismatic effect that may cause symptoms of asthenopia and intermittent diplopia. It is less of a problem for patients with a narrow near centration distance (NCD) since they will incur base out prism, which will cause excessive convergence well within normal fusional reserves which can be easily as high as 10Δ base out. Patients with a NCD significantly wider than the optical centres of their ready readers will incur base in prism, which causes the eyes to diverge and will cause symptoms at levels lower than 4Δ base in. Nevertheless, even with the highest power of ready reader (+4.00DS) the optical centres would need to be over 10mm outside of tolerance, or the patient be highly sensitive, for symptoms to be evident. The bruhaha that has surrounded the supply of ready readers since deregulation of supply in 1984 says more about the indignity of opticians than the actual evidence that any harm might come to pass. Opticians, especially those that are pre-presbyopic, should not dismiss ready-readers out of hand, but should recognise their benefit to patients while simultaneously explaining their limitations that may be solved with prescription spectacles or other solutions.

Other options for emmetropic presbyopia

Emmetropes, having enjoyed over four decades of perfect vision, are often taken by surprise by presbyopia, and certainly education of patients in the UK does not prepare patients for what will inevitably happen. Disinclined to wear spectacles, presbyopic emmetropes can be a very challenging group to satisfy. However, with vanity often playing a part, they are often willing to consider anything but spectacles as a solution to their new-found problem, with eye drop treatment, mentioned in the case study above now one of their many options.

Eye surgery to correct presbyopia

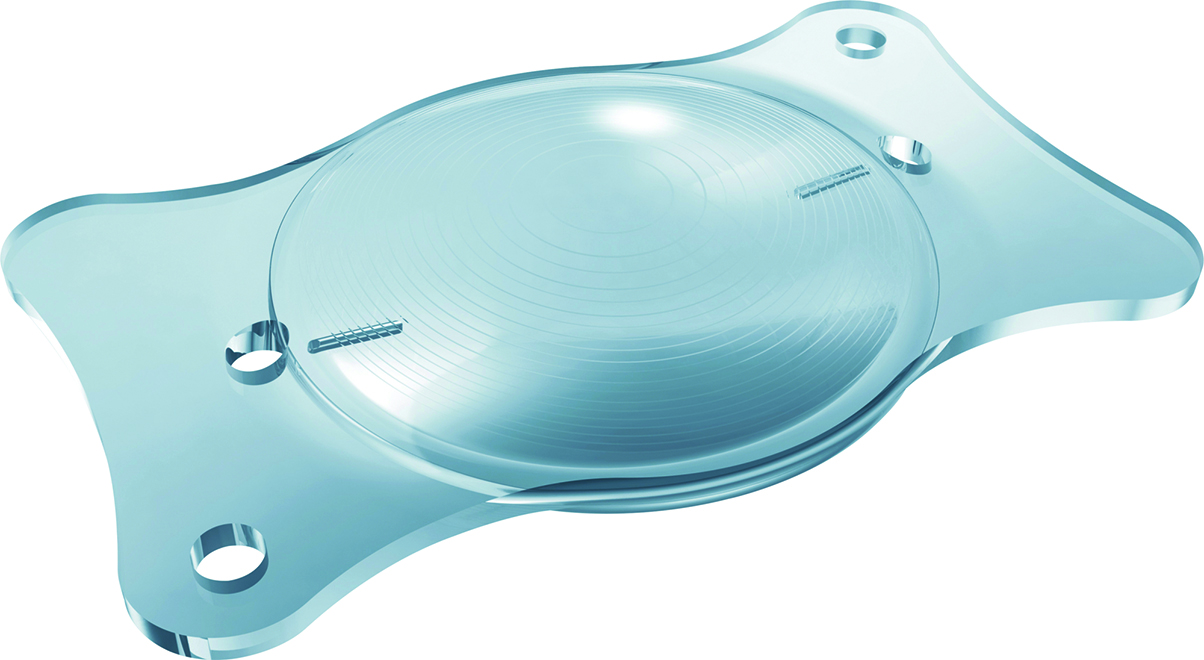

A surprising number of emmetropic patients enquire about surgical options to correct their presbyopia (figure 7). In the main patients are likely to be offered ‘monovision’ where one eye is left for distance, and the other eye is corrected for near, usually by a laser refractive technique such as LASIK or LASEK. Another technique that can be employed is clear lens extraction. If monovision is required, then the crystalline lens from one eye is removed and replaced with a single vision intraocular lens focused for near. Alternatively, one or both eyes can be fitted with multifocal implants.

Figure 7: A multifocal intraocular lens used int eh surgical correction of presbyopia

Contact lenses

Patients considering surgery might be well advised to try contact lenses first in order to experience the standard of vision that is likely. Both monovision and multifocal lenses are options. However, patients with excellent distance vision need to be made aware of the need to necessarily compromise either their distance visual acuity or their stereopsis or both in order to relieve symptoms of presbyopia. With appropriately set expectations, emmetropes can make committed successful contact lens wearers and often abandon the idea of refractive surgery once they have considered the relative risks during the informed consent process that should take place for either intervention.

Correcting presbyopia; the ametropic presbyope

Presbyopes who are myopic or hyperopic, with or without significant levels of astigmatism, can also be corrected by monovision or multifocal contact lenses, and within limits are also likely to be suitable for refractive surgery. Experience with post cataract patients suggests that surgical monovision is not tolerated as well as many ophthalmologists might have us believe although many patients are truly delighted. In higher adds monovision contact lenses are fraught with problems relating to lack of stereopsis, so it may be better for presbyopic contact lens wearers to graduate into multifocal contact lenses and bypass monovision altogether for ease of adaptation.

Generally, it is fair to say that the advent of presbyopia makes refractive eye surgery less attractive and is a key reason that contact lens wearers revert to spectacles and substantially reduce contact lens wear or give up altogether.

The correction of presbyopia with spectacles forms the mainstay of optometric practice and patients have many options to choose from including: separate pairs of distance, reading and intermediate spectacles; bifocals; trifocals; progressive addition lenses; low add boost progressive lenses; occupational progressives and degressive lenses etc. Spectacle correction of presbyopia will form the basis of the next article.

- Peter Black MBA FBDO FEAOO is senior lecturer in ophthalmic dispensing at the University of Central Lancashire, Preston, and is a practical examiner, practice assessor, exam script marker, and past president of the Association of British Dispensing Opticians. Tina Arbon Black BSc (Hons) FBDO CL is director of accredited CET provider Orbita Black Limited, an ABDO practical examiner, practice assessor and exam script marker, and a distance learning tutor for ABDO College

References

- Schwartz S. Geometrical and Visual Optics 3rd Edn. America: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019 p.117.

- Medscape. FDA Approves eye drops for presbyopia. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/961999#:~:text=The%20US%20Food%20and%20Drug,in%20a%20pinhole%2Dcamera%20effect. Accesses 9th November 2021.

- Freeman C. Evans B. Investigation of the causes of non-tolerance to optometric prescriptions for spectacles. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2009; 20(1): 1-11. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1475-1313.2009.00682.x Accessed 1st November 2021

- Burns D. Allen P. Edgar D. Evans B. Sources of error in clinical measurement of the amplitude of accommodation. Journal of Optometry. 2020;13(1): 3-14. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1888429619300421 Accessed 1st November 2021.