Dementia is an umbrella term used to describe symptoms of memory loss, difficulties with thinking, problem solving and language. Changes in mood and behaviour are common. The symptoms may be mild to begin with and become more severe, depending on the underlying condition. The most common cause for dementia is Alzheimer’s disease, accounting for 60 to 80% of dementia. Other types of dementia include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal disorders, posterior cortical atrophy and mixed dementia. Dementia can affect the visual areas of the brain, which leads to changes in visual perception and visual processing. When the world is perceived differently, this has an effect on behaviour and daily functioning.

Alzheimer's disease and posterior cortical atrophy

Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease is a result of the formation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles and a loss of connections between neurons in the brain. Changes in the brain occur many years before the onset of symptoms. Damage usually starts in the hippocampus and the entorhinal cortex and becomes more widespread as the disease progresses. Memory loss, word-finding and reasoning skills are some of the early symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. As the disease progresses, patients may experience problems with route finding, recognising faces and objects, managing more complex situations, planning and communication skills. Processing visual information is an essential aspect in many of these functions and damage to the visual processing pathways and networks impacts on the ability to carry out everyday tasks. In Alzheimer’s disease, visual difficulties and hallucinations tend to occur later on in the disease process.

In contrast, in posterior cortical atrophy, also known as Benson’s syndrome, visual difficulty tends to be one of the first symptoms. Although these are two separate conditions, posterior cortical atrophy and Alzheimer’s disease are often grouped together. In posterior cortical atrophy, the higher visual processing functions are impaired. A small study1 (by Nestor et al) showed selective hypometabolism in the occipito-parietal region (right much worse than left), leading to oculomotor apraxia and optic ataxia in patients with posterior cortical atrophy. Patients with Alzheimer’s disease tend to present to the ophthalmologist at a later stage in their disease process when visual changes develop. Symptoms vary from blurred vision and reading difficulties to more complex presentations related to dysfunction of the ventral and dorsal stream networks.2 Studies on this topic often ascribe visual symptoms to Alzheimer’s disease without making a distinction between Alzheimer’s disease and posterior cortical atrophy. As a rule of thumb, if visual symptoms are the first presenting symptoms, a diagnosis of posterior cortical atrophy is more likely. If the visual symptoms develop later in the disease process, a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is more likely. The nature of the symptoms can be very similar as both conditions can affect the same visual networks in the brain.

Structural changes in Alzheimer's disease

Degeneration of axonal nerves and loss of retinal ganglion cells are associated with visual impairment in Alzheimer’s disease.3 An association between Alzheimer’s disease and glaucoma has been suggested due to the similarity in risk factors, common features and pathophysiological mechanisms. However, more research is needed to fully understand this relationship and the impact on diagnosis and treatment.4 In Alzheimer’s disease, patients with optic disc atrophy tend to have impaired visual acuity, stereopsis, contrast sensitivity and colour vision (blue-violet).2

Basic visual functions

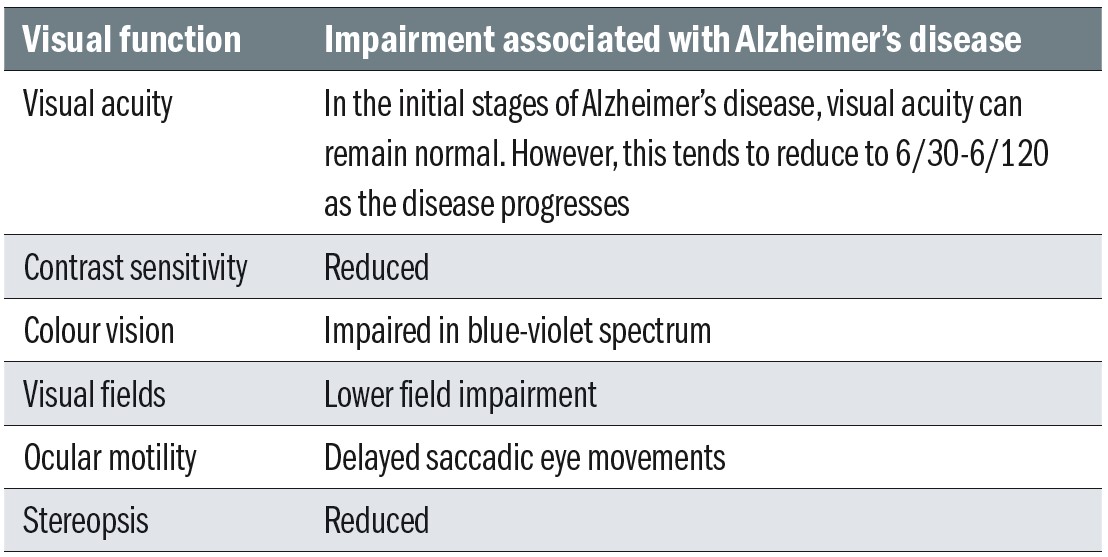

Basic visual functions are often impaired in Alzheimer’s disease. Table 1 provides an overview of visual function impairment associated with Alzheimer’s disease. If a patient presents in the optometric practice with any form of dementia, assessment of these functions is indicated in order to help the patient and their family and carers to understand the visual symptoms and to suggest possible adaptations and strategies to improve functioning.

Table 1: Basic visual functions in Alzheimer’s disease2,8

Table 1: Basic visual functions in Alzheimer’s disease2,8

Higher processing functions

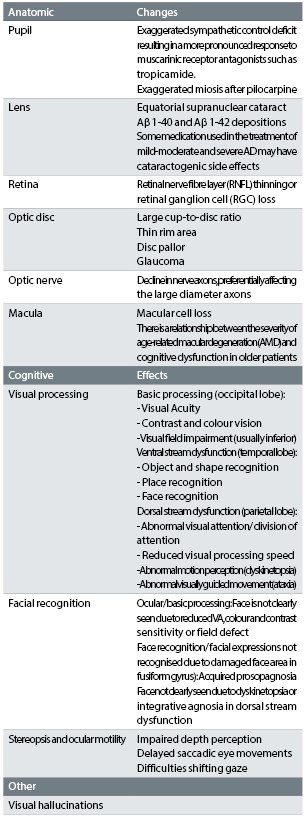

Basic visual functions are commonly assessed in the optometric practice and are very well understood by eye care professionals. However, patients with Alzheimer’s disease often have complex visual complaints due to dysfunction of the ventral and dorsal stream networks.2,3 These networks affect recognition, visual attention and spatial awareness. Each network plays a unique role in visual processing while both networks are closely dependent on one another. As the disease progresses, visual hallucinations become more common. Table 2 summarises the anatomical and higher functional changes with Alzheimer’s disease.

Table 2: Anatomical and higher functional changes with Alzheimer’s disease

Table 2: Anatomical and higher functional changes with Alzheimer’s disease

Ventral stream network

The ventral stream network is primarily responsible for recognition. It is sometimes referred to as the ‘What pathway’. Affected patients experience difficulties with recognising objects (object agnosia) and faces (prosopagnosia, figure 2) and with route finding (topographic agnosia).2,5 Impaired oral reading has also been associated with ventral stream dysfunction.6 Recognition of facial identity and naming facial emotions are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. However, in a number of patients, the ability to understand facial emotions remains intact. This ability is essential for non-verbal communication, which is not always affected in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.7 Some patients have severe prosopagnosia and fail to recognise their own reflection. If this causes distress, one could consider removing mirrors.

Dorsal stream network

The dorsal stream network is primarily responsible for visual attention and spatial awareness. It is sometimes referred to as the ‘Where pathway’. Affected patients experience difficulties with visually guided reach (optic ataxia), seeing more than one object at once (simultanagnosia), movement perception (dyskinetopsia), controlling voluntary purposeful eye movements (oculomotor apraxia) and functioning in complex scenes.2,8

Visual hallucinations

Visual hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease are thought to originate from pathology of the occipital lobe. Patients who experience visual hallucinations often have poorer visual acuity and more severe cognitive impairment and visual agnosia.9,2,10 Visual hallucinations could act as a signal to prompt further assessments. A study by Chapman et al11 showed that Alzheimer’s patients with uncorrected refractive error or significant cataract tend to have more hallucinations and that it is worth treating these conditions to improve vision and reduce hallucinations.

It is worth considering a similar approach with any other eye condition that reduces visual functions and for which treatment is available. Visual hallucinations vary in presentation. Patients commonly report seeing faces, animals or patterns. In Alzheimer’s disease, unlike ocular visual impairment, the hallucinations may not be purely visual; some patients report hearing voices and even start conversations with the imaginary person. Hallucinations can be upsetting and the Alzheimer’s Association12 offers the following advice:

- Find out if the hallucination is upsetting and if it causes the person to do something dangerous

- Offer reassurance by responding in a calm and supportive manner and by acknowledging the person’s feelings

- Use distractions, such as going for a walk, having a conversation, turning on the light or listening to music

- Respond honestly, stating that you are unable to see what they see, acknowledging that the patient does see things

- Modify the environment to avoid sounds, shadows, reflections or distortions that could be misinterpreted

Living with Alzheimer's disease

This section describes a few case scenarios of patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Case 1

A woman was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in her late seventies. She initially lived on her own with support from her family, who managed her finances and helped her with grocery shopping and cleaning. When she no longer remembered to get up, get dressed and have her daily meals, a care package was arranged to provide extra support. A lack of initiation is a common symptom in Alzheimer’s disease.13 She was increasingly found wandering (topographic agnosia) and thankfully, she was equipped with a medical alert necklace with a phone number of a close relative, which enabled people to bring her back to her apartment. As her disease progressed she had trouble recognising faces and mistook strangers for friends, but this was not appreciated at the time. This left her extremely vulnerable, especially when people came to her door.

Unfortunately, she was taken advantage of when an ill-disposed person made his way in and stole some valuable items. After this incident, her dementia progressed rapidly and her anxiety increased. Her cognitive decline meant that she burnt herself on the cooker and in the shower or hot tap. She regularly put meat and other food items on her radiator, putting herself at risk of food poisoning. When she could no longer live alone, she moved in with her daughter. This compromised living situation was meant to be temporarily, but became much longer due to the waiting lists for placement in a nursing home. She became more agitated and anxious as time went by, which had a significant impact on her daughter who juggled family life with her husband and teenage children. No support was offered in terms of understanding dementia and caring for someone with dementia. Her family did not understand why she was paranoid and constantly seemed to see things that no one else perceived.

When she eventually lived in a nursing home, symptoms of agnosia became more apparent. Her family realised that she did not recognise people or even herself in the mirror (acquired prosopagnosia). However, she was able to describe faces in great detail. When looking at holiday photographs from her grandchildren, she commented on the colours and could no longer recognise that they were showing people, objects or scenes (object agnosia). Her visual hallucinations and illusions became more disturbing, which made her feel very anxious.

In a situation like this, it can be extremely helpful for the patient and their family and carers to gain insight into the visual processing dysfunctions. This allows them to adapt the environment and to approach the patient with understanding and reassurance, which can lead to less anxiety and stress.

Case 2

A man in his eighties was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Although the diagnosis was made at this stage, there were indications that the disease started many years earlier. One of the first symptoms was short term memory loss. He did not seem to remember things that were said to him and struggled to follow instructions. Initially it was thought that his hearing impairment was the primary reason for not recalling information. After all, if information is not heard, it cannot be stored and therefore not be recalled.

It can be challenging to unpick what is attributable to dementia and what is a result of hearing loss. Combined cognitive impairment and hearing impairment is common in the elderly population14-20 and both conditions together can lead to signifiant dysfunction. He also struggled with finding things, even if they were right in front of him (possible dorsal stream dysfunction). Remembering where objects were stored in kitchen cupboards led to frustration and misunderstandings. Strategies were discussed to improve visual search and optimal storage was discussed to make it easier to find things around the house. Although he was able to find his way around his own neighbourhood, he struggled with route finding in less familiar places (topographic agnosia). He worried if it was no longer safe to take a bus to the town centre in case he could not find his way back home.

Over time, his ability to follow instructions became worse and he could no longer remember what he had planned for the day ahead. He coped less well in busy environments and became nervous when he felt that too many demands were placed on him as he could no longer remember what he needed to do and worried he might miss something important. As time went by, he started to trip over things and lost confidence when going out in his own neighbourhood. A lower field impairment contributed to his problems with mobility and he was advised to use a cane or hiking pole to feel the ground ahead of him. Although he still met the vision standards for driving, driving safety was thought to be compromised and he was advised to stop driving. A combination of reduced visual acuity and contrast sensitivity caused problems with reading. His reading improved considerably with an illuminated hand magnifier.

Caring for a person with AD

The world as we experience it, is a representation of the world created in the brain. In most cases, the representation in the brain closely matches reality. However, in patients with brain damage, including Alzheimer’s disease, the representation of the world is less accurate and their behaviour changes in response to their perceived world. Their behaviour is not always well understood by those who care for the person with dementia. However, a patient with Alzheimer’s disease may be agitated or aggressive because of something they perceive. This can lead to fatigue, depression or anger in as much as 87 % of caregivers.2 Case 1 shows that the changing needs of a patient can result in major adjustments for the family who want to care for their loved one. Holroyd et al recommend education for families to reduce the risk of harm due to wandering, accidents and using equipment that they can no longer handle.2

Caregivers could benefit from charities and societies such as Alzheimer’s UK in order to gain more understanding of the condition and receive peer support. The needs of caregivers should not be overlooked and support should be offered if this is required. At the same time, there is a desire among health and social care practitioners to receive more training to gain better understanding of the less well-recognised symptoms of dementia,21 including impaired visual processing. Understanding the visuoperceptual dysfunction is an important step to improve quality of life.8 In the author’s experience training of this kind is much appreciated by these professionals and has benefited patients in their care.

Communicating with a person with dementia

For a thorough review of communication with Alzheimer’s, turn to page 24. Communicating with and caring for people with dementia can be difficult as requests are not always well understood. Some patients may refuse to be assessed by a healthcare professional and therefore it is essential to be familiar with effective communication strategies. The patient should be at the centre of the communication and be addressed directly with clear and explicit instructions that are easy to follow. The procedure should be easy to perform for the individual patient.

It tends to be easier for patients to receive instructions, rather than choices.22 One could state what is about to happen and why, followed by: ‘Is that OK?’, rather than asking an open question, such as: ‘I wonder if you would like me to do X.’ Being able to perform clinical procedures can help the patient stay safe and healthy, but one has to remember the importance of informed consent and/or assent. The University of Nottingham has produced an excellent free resource for health care professionals on this topic.22

Conclusion

Alzheimer’s disease usually starts with memory loss, impaired reasoning skills and problems with word finding. As the disease progresses, the visual areas of the brain can be affected leading to less well known visual processing disorders. Alzheimer’s disease can affect basic functions such as visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, visual fields and colour vision. When the occipital and parietal lobe are affected, this can lead to visual agnosias and disorientation as well as visual hallucinations. Optometrists can play an important role in identifying some of these visual problems and explaining it to the patient and their family and carers. This information can be used to make adjustments in the patient’s environment and to approach the patient in a different way, offering more assurance and support.

- Cirta Tooth Tooth is a hospital optometrist based in Edinburgh with a special interest is low vision and functional vision.

References

- Nestor PJ, Caine D, Hodges JR et al. 2003. The topography of metabolic deficits in posterior cortical atrophy (the visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease) with FDG-PET. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry 74(11), pp.1521-1529.

- Holroyd S and Shepherd M. 2001. Alzheimer’s disease: a review for the ophthalmologist. Survey of Ophthalmology 45(6), pp.516-524.

- Kirby E, Bandelow S and Hogervorst E. 2010. Visual impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: a critical review. Journal of Alzheimers Disease 21(1), pp.15-34.

- Mancino R, Martucci A, Cesareo M et al. 2018. Glaucoma and Alzheimer disease: one age-related neurodegenerative disease of the brain. Current Neuropharmacology 16(7), pp.971-977.https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666171206144045

- Pal S, Sanyal D, Das SK et al. Visual manifestations in Alzheimer’s disease: a clinic-based study from India. American Journal of Alzheimers Disease and other Dementias 28(6), pp.575-582.

- Glosser G, Baker KM, Clark CM et al. 2002. Disturbed visual processing contributes to impaired reading in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia 40(7), pp.902-909.

- Roudier M, Marcie P, Boller F et al. 1998. Discrimination of facial identity and of emotions in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 154(2), pp.151-158.

- Lenoir H and Sieroff A. 2019. Visual perceptual disorders in Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatrie et Psychologie Neuropsychiatrie de Vieillissement 17(3), pp.307-316.

- Holroyd S, Shepherd ML and Downs JH. 2000. Occipital atrophy is associated with visual hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 12(1), pp.25-28.

- Lin SH, Yu CY and Pai MC. 2006. The occipital white matter lesions in Alzheimer’s disease patients with visual hallucinations. Clinical Imaging 30(6), pp.388-393.

- Chapman FM, Dickinson J, Ballard C et al. 1999. Association among visual hallucinations, visual acuity, and specific eye pathologies in Alzheimer’s disease: treatment implications. American Journal of Psychiatry 156(5), pp1983-1985.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2021. Hallucinations- Coping strategies. Available at: https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/hallucinations [Accessed 18 January 2022].

- Cook C, Fay S and Rokwood K. 2008. Decreased initiation of usual activities in people with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a descriptive analysis from the VISTA clinical trial. International Psychogeriatrics 20(5), pp.952-963. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208007230.

- Alattar AA, Bergstrom J, Laughlin GA et al. 2020. Hearing impairment and cognitive decline in older, community-dwelling adults. Journals of Gerontology Series A-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 75(3), pp.567-573.

- Dong SH, Park JM, Kwon OE et al. 2019. The relationship between age-related hearing loss and cognitive disorder. Journal for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology Head and Neck Surgery 81(5-6), pp.265-273.

- Golub JS, Brickman AM, Ciarleglio AJ et al. 2020. Association of subclinical hearing loss with cognitive performance. Journal of the American Medical Association Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 146(1), pp.57-67.

- Huber M, Roesch S, Pletzer B et al. 2019. Cognition in older adults with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss compared to peers with normal hearing for age. International Journal of Audiology 59(4), pp.254-262.

- Michalowsky B, Hoffmann W, Kostev K. 2019. Association between hearing and vision impairment and risk of dementia: results of a case-control study based on secondary data. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 11. Article Number 363.

- Morita Y, Sasaki T, Takahashi K. et al. 2019. Age-related hearing loss is strongly associated with cognitive decline regardless of the APOE4 polymorphism. Otology and Neurology 40(10), pp.1263-1267.

- Yurtogullari S, Koean EG, Vural G et al. 2020. The relationship of presbycusis with cognitive functions. Turkish Journal of Geriatrics 23(1), pp.75-81.

- McIntyre A, Harding E, Crutch S et al. Health and social care practitioner’s understanding of the problems of people with dementia-related visual processing impairment. Health and Social Care in the Community 27(4), pp.982-990.

- O’Brien R, Goldberg S, Harwood R et al. 2017. Advanced communication: communicating with a patient with dementia who is refusing care. Available at: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/helm/dev-test/dementia_and_requests/index.html [Accessed 18 January 2022].